STTR: An Assessment of the Small Business Technology Transfer Program (2016)

Chapter: Appendix A: Overview of Methodological Approaches, Data Sources, and Survey Tools

Appendix A

Overview of Methodological Approaches, Data Sources, and Survey Tools

This series of reports on the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and the Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs at the Department of Defense (DoD), National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Department of Energy (DoE), and National Science Foundation (NSF) represents a second-round assessment of the program undertaken by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.1 The first-round assessment, focusing on SBIR and conducted under a separate ad hoc committee, resulted in a series of reports released from 2004 to 2009, including a framework methodology for that study and on which the current methodology builds.2

The current study is the first to focus on the STTR program, and it addresses the twin objectives of assessing outcomes from the STTR program and of providing recommendations for improvement.3 Section 1c of the Small

________________

1Effective July 1, 2015, the institution is called the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. References in this report to the National Research Council or NRC are used in an historic context identifying programs prior to July 1.

2National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2004.

3The methodology developed as part of the first-round assessment of the SBIR program also identifies two areas that are excluded from the purview of the study: “The objective of the study is not to consider if SBIR should exist or not—Congress has already decided affirmatively on this question. Rather, we are charged with providing assessment-based findings of the benefits and costs of SBIR . . . to improve public understanding of the program, as well as recommendations to improve the program’s effectiveness. It is also important to note that, in accordance with the Memorandum of Understanding and the Congressional mandate, the study will not seek to compare the value of one area with other areas; this task is the prerogative of the Congress and the Administration acting through the agencies. Instead, the study is concerned with the effective review of each area.” National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology. In implementing this approach in the context of the current round of SBIR assessments, we have opted to focus more deeply on operational questions.

Business Administration (SBA) STTR Directive states program objectives as follows: “The statutory purpose of the STTR Program is to stimulate a partnership of ideas and technologies between innovative small business concerns (SBCs) and Research Institutions through Federally-funded research or research and development (R/R&D).”4

SBA also provides further guidance on its web site, which aligns the objectives of STTR more closely with those of SBIR: “(1) stimulate technological innovation, (2) foster technology transfer through cooperative R&D between small businesses and research institutions, and (3) increase private-sector commercialization of innovations derived from federal R&D.”5

The STTR program, on the basis of highly competitive solicitations, provides modest initial funding for selected Phase I projects (in most cases up to $150,000) and for feasibility testing and further Phase II funding (in most cases up to $1.5 million) for qualifying Phase I projects.

DATA CHALLENGES

From a methodology perspective, assessing this program presents formidable challenges. Among the more difficult are the following:

- Lack of data. The agencies have only limited ability to track outcomes data, both in scope (share of awards tracked) and depth (time tracked after the end of the award). There are no published or publicly available outcomes data.

- Intervening variables. Analysis of small innovative businesses suggests that they are often very path dependent and, hence, can be deflected from a given development path by a wide range of positive and negative variables. A single breakthrough contract—or technical delay—can make or break a company.

- Lags. Not only do outcomes lag awards by a number of years, but also the lag itself is highly variable. Some companies commercialize within 6 months of award conclusion; others take decades. And often, revenues from commercialization peak many years after products have reached markets.

ESTABLISHING A METHODOLOGY

The methodology utilized in this second-round study of the SBIR-STTR programs builds on the methodology established by the committee that completed the first-round study.

________________

4Ibid., p. 3.

Publication of the 2004 Methodology

The committee that undertook the first-round study and the agencies under study acknowledged the difficulties involved in assessing the SBIR-STTR programs. Accordingly, that study began with development of the formal volume on methodology, which was published in 2004 after undergoing the standard Academies peer-review process.6

The established methodology stressed the importance of adopting a varied range of tools based on prior work in this area, which meshes with the methodology originally defined by the first study committee. The first committee concluded that appropriate methodological approaches

build from the precedents established in several key studies already undertaken to evaluate various aspects of the SBIR/STTR. These studies have been successful because they identified the need for utilizing not just a single methodological approach, but rather a broad spectrum of approaches, in order to evaluate the SBIR/STTR from a number of different perspectives and criteria.

This diversity and flexibility in methodological approach are particularly appropriate given the heterogeneity of goals and procedures across the five agencies involved in the evaluation. Consequently, this document suggests a broad framework for methodological approaches that can serve to guide the research team when evaluating each particular agency in terms of the four criteria stated above.7

Table A-1 illustrates some key assessment parameters and related measures to be considered in this study.

The tools identified Table A-1 include many of those used by the committee that conducted the first-round study of the SBIR-STTR programs. Other tools have emerged since the initial methodology review.

Tools Utilized in the Current STTR Study

Quantitative and qualitative tools being utilized in the current study of the STTR program include the following Academies activities:

- Surveys. An extensive survey of STTR award recipients as part of the analysis.

________________

6National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology, p. 2.

7Ibid.

TABLE A-1 Overview of Approach to SBIR-STTR Programs Assessment

| SBIR/STTR Assessment Parameters → | Quality of Research | Commercialization of SBIR-/STTR-Funded Research/Economic and Non-economic Benefits | Small Business Innovation/ Growth | Use of Small Businesses to Advance Agency Missions |

| Questions | How does the quality of SBIR-/STTR-funded research compare with that of other government funded R&D? | How effectively does SBIR/STTR support the commercialization of innovative technologies? What non-economic benefits can be identified? | How to broaden participation and expand the base of small innovative firms | How to increase agency support for commercializable technologies while continuing to support high-risk research |

| Measures | Peer-review scores, publication counts, citation analysis | Sales, follow-up funding, other commercial activities | Patent counts and other intellectual property/employment growth, number of new technology firms | Innovative products resulting from SBIR/STTR work |

| Tools | Case studies, agency program studies, study of repeat winners, bibliometric analysis | Phase II surveys, program manager discussions, case studies, study of repeat winners | Phase I and Phase II surveys, case studies, study of repeat winners | Program manager surveys, case studies, agency program studies, study of repeat winners |

| Key Research Challenges | Difficulty of measuring quality and of identifying proper reference group | Skew of returns; significant interagency and inter-industry differences | Measures of actual success and failure at the project and firm levels; relationship of federal and state programs in this context | Major interagency differences in use of SBIR/STTR to meet agency missions |

NOTE: Supplementary tools may be developed and used as needed. In addition, since publication of the methodology report, this committee has determined that data on outcomes from Phase I awards are of limited relevance.

SOURCE: National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2004, Table 1, p. 3.

- Case studies. In-depth case studies of 11 STTR recipients at the five study agencies. These companies were geographically and demographically diverse and were at different stages of the company lifecycle.

- Workshops. A workshop in 2015 on STTR to allow stakeholders, agency staff, and academic experts to provide insights into the programs’ operations, as well as to identify questions that should be addressed.

- Analysis of agency data. The agencies provided a range of datasets covering various aspects of agency STTR activities.

- Open-ended responses from STTR recipients. For the first time, survey responses included textual answers to provide a deeper view into certain questions. More than 500 responses were generated.

- Agency meetings. We discussed program operations with staff at all five study agencies, drawing out information both about the program and the challenges that they faced.

- Literature review. Since the start of our research in this area, a number of papers have been published addressing various aspects of the SBIR-STTR programs. In addition, other organizations—such as the Government Accountability Office (GAO)—have reviewed particular parts of the SBIR-STTR programs. Where useful, references to these works have been included in the course of this analysis.

Taken together with our deliberations and the expertise brought to bear by individual committee members, these tools provide the primary inputs into the analysis. For both the SBIR reports and for the current study, multiple research methodologies feed into every finding and recommendation. No finding or recommendation rested solely on data and analysis from the survey; conversely, survey data were used to support analysis throughout the report.

COMMERCIALIZATION METRICS AND DATA COLLECTION

Recent congressional interest in the SBIR-STTR programs has to a considerable extent focused on bringing innovative technologies to market. This enhanced attention to the economic return from public investments made in small business innovation is understandable. In its 2008 report on the SBIR program,8 the committee charged with the first-round assessment held that a binary metric of commercialization was insufficient. It noted that the scale of commercialization is also important and that there are other important milestones both before and after the first dollar in sales that should be included in an appropriate approach to measuring commercialization.

________________

8National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2008.

Challenges in Tracking Commercialization

Despite substantial efforts by the agencies, significant challenges remain in tracking commercialization outcomes for the STTR program. These include the following:

- Data limitations. Data tracking at the agencies varies widely in scale and scope. DoD and DoE utilize a similar web-based system, NSF uses a telephone-based approach, and NIH and NASA are developing their tracking programs.

- Linear linkages. Tracking efforts usually seek to link a specific project to a specific outcome. Separating the contributions of one project is difficult for many companies, given that multiple projects typically contribute to both anticipated and unanticipated outcomes.

- Lags in commercialization. Data from the extensive DoD commercialization database suggest that most projects take at least 2 years to reach the market after the end of the Phase II award. They do not generate peak revenue for several years after this. Therefore, efforts to measure program productivity must account for these significant lags.

- Attribution problems. Commercialization is often the result of several awards, not just one, as well as other factors, so attributing company-level success to specific awards is challenging at best.

Why New Data Sources Are Needed

Congress often seeks evidence about the effectiveness of programs or indeed about whether they work at all. This interest has in the past helped to drive the development of tools such as the Company Commercialization Report (CCR) at DoD, which captures the quantitative commercialization results of companies’ previous Phase II projects. However, in the long term the importance of tracking may rest more in its use to support program management. By carefully analyzing outcomes and CCR’s associated program variables, program managers will be able to manage their STTR portfolios more successfully.

In this regard, the STTR program can benefit from access to the survey data. The survey work provides quantitative data necessary to provide an evidence-driven assessment and, at the same time, allows management to focus on specific questions of interest, in this case related to operations of the STTR program itself.

SURVEY ANALYSIS

Traditional modes of assessing the SBIR-STTR programs include case studies, meetings, and other qualitative methods of assessment. These remain important components of the overall methodology, and a chapter in the current report is devoted to lessons drawn from case studies. However, qualitative assessment alone is insufficient.

2011-2014 Survey

The 2011-2014 Survey offers some significant advantages over other data sources. Specifically, it:

- provides a rich source of textual information in response to open-ended questions;

- probes more deeply into company demographics and agency processes;

- for the first time addresses principal investigators (PIs), not just company business officials;

- allows comparisons with previous data-collection exercises; and

- addresses other Congressional objectives for the program beyond commercialization.

For these and other reasons, we determined that a survey would be the most appropriate mechanism for developing quantitative approaches to the analysis of the STTR programs. At the same time, however, we are fully cognizant of the limitations of survey research in this case. Box A-1 describes a number of areas where caution is required when reviewing results.

This report in part addresses the need for caution by publishing the number of responses for each question and indeed each subgroup. As noted later in this discussion, the use of a control group was found to be infeasible.

Non-respondent Bias

The committee is aware that it is good practice where feasible to ascertain the extent and direction of non-respondent bias. We also acknowledge the likelihood that data from the survey may be affected by the undoubted survey deployment bias toward surviving firms.

Very limited information is available about SBIR/STTR award recipients: company name, location, and contact information for the PI and the company point of contact, agency name, and date of award (data on woman and minority ownership are not considered reliable). No detailed data are available on applicants who did not win awards. It is therefore not feasible to undertake detailed analysis of non-respondents, but the possibility exists that they would present a different profile than would respondents.

Non-respondent bias may of course work in more than one direction. Unsuccessful firms go out of business, but successful firms are often acquired by larger firms. As they are absorbed, staff are dissipated and units rearranged until PIs from these successful firms are also often unreachable. This is an especially significant instance of non-response bias in this case, as the well-known skew in outcomes for high-tech firms suggests that some of the most successful firms and projects are beyond the reach of the survey, and outcomes from these firms may account for a substantial share of overall outcomes from the program.

These inevitable gaps among both successful and unsuccessful firms are compounded by the substantial amount of movement by PIs independent of firm outcomes. PIs move to new firms, move to academia, retire, or in some cases die. In almost all cases, their previous contact information becomes unusable. Although in theory it is possible to track PIs to a new job or into retirement, in practice and given the resources available, the committee did not consider this to be an appropriate use of limited funding.

Finally, in its recent study of the SBIR program at DoD,9 the committee compared outcomes drawn from the Academies survey and the CCR database and found that, where there was overlap in the questions, outcomes were approximately similar even though the DoD database is constructed using a completely different methodology and is mandatory for all firms participating in the SBIR-STTR programs. Although equivalent cross-checks are not available for the other agencies, the comparison with CCR data does provide a direct cross-check for one-half of all SBIR/STTR awards made and also suggests that the Academies survey methodology generates results that can be extended with some confidence to the other study agencies.

DEPLOYMENT OF THE 2011-2014 ACADEMIES PHASE II SURVEY

The Academies contracted with Grunwald Associates LLC to administer surveys to DoD, NASA, and NSF Phase II award recipients in fall 2011 and to NIH and DoE recipients in 2014. Delays in contracting with NIH and DoE resulted in the two-track deployment noted above. The Academies’ 2011-2014 Survey is built closely on the previous 2005 Survey, but it is also adapted to draw on lessons learned and includes some important changes discussed in detail below. A subgroup of this committee with particular expertise in survey methodology also reviewed the survey and incorporated current best practices.10

________________

9National Academies, SBIR at the Department of Defense, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2014.

10Delays at NIH and DoE in contracting, combined with the need to complete work contracted with DoD, NSF, and NASA led us to proceed with the survey at the remaining three agencies first, in 2011, followed by the NIH-DoE survey in 2014.

BOX A-1

Multiple Sources of Bias in Survey Responsea

Large innovation surveys involve multiple sources of potential bias that can skew the results in different directions. Some potential survey biases are noted below.

- Successful and more recently funded companies are more likely to respond. Research by Link and Scott demonstrates that the probability of obtaining research project information by survey decreases for less recently funded projects and increases the greater the award amount.b Winners from more distant years are difficult to reach: small businesses regularly cease operations, are acquired, merge, or lose staff with knowledge of SBIR/STTR awards. This may skew commercialization results downward, because more recent awards will be less likely to have completed the commercialization phase.

- Success is self-reported. Self-reporting can be a source of bias, although the dimensions and direction of that bias are not necessarily clear. In any case, policy analysis has a long history of relying on self-reported performance measures to represent market-based performance measures. Participants in such retrospective analyses are believed to be able to consider a broader set of allocation options, thus making the evaluation more realistic than data based on third-party observation.c In short, company founders and/or PIs are in many cases simply the best source of information available.

- Survey sampled projects from PIs with multiple awards. Projects from PIs with large numbers of awards were underrepresented in the sample, because PIs could not be expected to complete a questionnaire for each of numerous awards over a 10-year time frame.

- Failed companies are difficult to contact. Survey experts point to an “asymmetry” in the survey’s ability to include failed companies for follow-up surveys in cases where the companies no longer exist.d It is worth noting that one cannot necessarily infer that the SBIR/STTR project failed; what is known is only that the company no longer exists.

- Not all successful projects are captured. For similar reasons, the survey could not include ongoing results from successful projects in companies that merged or were acquired before and/or after commercialization of the project’s technology. This is the outcome for many successful companies in this sector.

- Some companies are unwilling to fully acknowledge SBIR/STTR contribution to project success. Some companies may be unwilling to acknowledge that they received important benefits from participating in

-

public programs for a variety of reasons. For example, some may understandably attribute success exclusively to their own efforts.

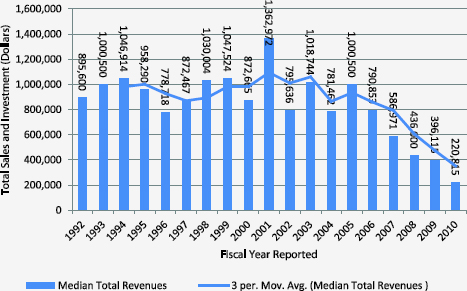

- Commercialization lag. Although the 2005 Survey broke new ground in data collection, the amount of sales made—and indeed the number of projects that generated sales—are inevitably undercounted in a snapshot survey taken at a single point in time. On the basis of successive data sets collected from SBIR/STTR award recipients, it is clear that total sales from all responding projects will be considerably greater than can be captured in a single survey.e This underscores the importance of follow-on research based on the now-established survey methodology. Figure Box A-1 illustrates this impact in practice at DoD: projects from fiscal year 2006 onward have not yet completed commercialization as of August 2013.

FIGURE Box A-1 The impact of commercialization lag.

SOURCE: DoD Company Commercialization Database.

a The limitations described here are drawn from the methodology outlined for the previous survey in National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the Department of Defense, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009.

b Albert N. Link and John T. Scott, Evaluating Public Research Institutions: The U.S. Advanced Technology Program’s Intramural Research Initiative, London: Routledge, 2005.

c Although economic theory is formulated on what is called “revealed preferences,” meaning that individuals and companies reveal how they value scarce resources by how they allocate those resources within a market framework, quite often expressed preferences are a better source of information, especially from an evaluation perspective. Strict adherence to a revealed preference paradigm could lead to misguided policy conclusions because the paradigm assumes that all policy choices are known and understood at the time that an individual or company reveals its preferences and that all relevant markets for such preferences are operational. See Gregory G. Dess and Donald

W. Beard, “Dimensions of organizational task environments,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 29: 52-73, 1984; Albert N. Link and John T. Scott, Public Accountability: Evaluating Technology-Based Institutions, Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1998.

d Albert N. Link and John T. Scott, Evaluating Public Research Institutions.

e Data from the National Research Council assessment of the SBIR program at NIH indicate that a subsequent survey taken 2 years later would reveal substantial increases in both the percentage of companies reaching the market and the amount of sales per project. See National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the National Institutes of Health, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009.

The primary objectives of the 2011-2014 Survey are to

- provide an update of the program “snapshot” taken in 2005, maximizing the opportunity to identify trends within the program;

- probe more deeply into program processes, with the help of expanded feedback from participants and better understanding of program demographics; and

- reduce costs and shrink the time required by combining three 2005 questionnaires—for the company, Phase I, and Phase II awards, respectively—into a single survey questionnaire.

The survey was therefore designed to collect the maximum amount of data, consistent with our commitment to minimizing the burden on individual respondents.

In light of these competing considerations, the committee determined that it would be more useful and effective to administer the survey to PIs—the lead researcher on each project—rather than to the registered company point of contact (POC), who in many cases would be an administrator rather than a researcher. This decision was reinforced by difficulties in accessing current POC information. Key areas of overlap between the 2005 and 2014 surveys are captured in Table A-2.

Starting Date and Coverage

The 2011-2014 Survey included awards made from fiscal year (FY)1998-2007 for DoD, DoE, and NSF and for FY2001 to FY2010 inclusive for NIH and DoE. This end date allowed for completion of Phase II-awarded projects (which nominally fund 2 years of research) and provided a further 2 years for commercialization. This time frame was consistent with the previous survey, administered in 2005, which surveyed awards from FY1992 to FY2001. It was also consistent with a previous GAO study, which in 1991 surveyed awards made through 1987.

The aim in setting the overall time frame at 10 years was to reduce the impact of difficulties in generating information about older awards because some companies and PIs may no longer be in place and memories fade over time.

TABLE A-2 Similarities and Differences: 2005 and 2014 Surveys

|

Item |

2005 Survey | 2014 Survey |

| Respondent selection | ||

|

Focus on Phase II winners |

||

|

All qualifying awards |

||

|

PIs |

||

|

POCs |

||

|

Max number of questionnaires per respondent |

<20 | 2 |

| Distribution | ||

|

|

No | |

|

|

||

|

Telephone follow-up |

||

| Questionnaire | ||

|

Company demographics |

Identical | Identical |

|

Commercialization outcomes |

Identical | Identical |

|

IP outcomes |

Identical | Identical |

|

Women and minority participation |

||

|

Additional detail on minorities |

||

|

Additional detail on PIs |

||

|

New section on agency staff activities |

||

|

New section on company recommendations for SBIR/STTR |

||

|

New section on STTR |

||

|

New section capturing open-ended responses |

Determining the Survey Population

Following the precedent set by both the original GAO study and the first round of Academies analysis, we differentiate between the total population of STTR recipients, the preliminary survey target population, and the effective population for this study, which is the population of respondents that were reachable.

Initial Filters for Potential Recipients

Determining the effective study population required the following steps:

- acquisition of data from the five study agencies covering record-level lists of award recipients during the relevant fiscal years;

- elimination of records that did not fit the protocol agreed upon by the committee—namely, a maximum of two questionnaires per PI (in cases where PIs received more than two awards). In these cases, awards were selected first by program (STTR, then SBIR), then by agency (in order: NSF, NASA, and DoD for 2011 and DoE and NIH for 2014), then by year (oldest first), and finally by random number; and

- elimination of records for which there were significant missing data.

This process of excluding awards either because they did not fit the selection profile approved by the committee or because the agencies did not provide sufficient or current contact information reduced the total STTR award list for the five agencies from 1,501 awards to a preliminary survey population of 1,400 awards.

Secondary Filters to Identify Recipients with Active Contact Information

This nominal population still included many potential respondents whose contact information was formally complete in the agency records but who were no longer associated with the contact information provided and hence effectively unreachable. This is not surprising given that small businesses experience considerable turnover in personnel and that the survey reaches back to awards made in FY1998. Recipients may have switched companies, the company may have ceased to exist or been acquired, or telephone and email contacts may have changed, for example. Consequently, we utilized two further filters to help identify the effective survey population.

- First, contacts for which the email address bounced twice were eliminated. Because the survey was delivered via email, the absence of a working email address disqualified the recipient. This eliminated approximately 20 percent of the preliminary population.

- Second, email addresses that did not officially “bounce” (i.e., return to sender) may still in fact not be active. Some email systems are configured to delete unrecognized email without sending a reply; in other cases, email addresses are inactive but not deleted. So a non-bouncing email address did not equal a contactable PI. Accordingly, Grunwald Associates made efforts to contact by telephone all non-respondents at the five agencies. Up to two calls were made, and outcomes from the telephone calls were used to further filter non-contactable PIs. Thirty seven percent of the preliminary population was non-contactable by telephone.11

________________

11This percentage includes only those individuals whose telephone contact information was clearly no longer current, for example, the phone number was invalid, the company was out of business, or the PI no longer worked at the company.

Deployment

The 2011 Survey opened in fall 2011 and the 2014 Survey in winter 2014. Both were deployed by email, with voice follow-up support. Up to four emails were sent to the effective population (emails discontinued once responses were received). In addition, two voice mails were delivered to non-respondents between the second and third and between the third and fourth rounds of email. In total, up to six efforts were made to reach each questionnaire recipient. The surveys were open for 11 and 18 weeks, respectively.

Response Rates

Standard procedures were followed to conduct the survey. These data collection procedures were designed to increase response to the extent possible within the constraints of a voluntary survey and the survey budget. The population surveyed is a difficult one to contact and obtain responses from, as evidence from the literature shows. Under these circumstances, the inability to contact and obtain responses always raises questions about potential bias of the estimates that cannot be quantified without substantial extra efforts that would require resources beyond those available for this work.

Table A-3 shows the response rates for STTR at the five agencies, based on both the preliminary study population prior to adjustment and the effective study population after all adjustments.

Effort at Comparison Group Analysis

Several readers of the reports in the first-round analysis of the SBIR-STTR programs suggested the inclusion of comparison groups in the analysis.

TABLE A-3 2011-2014 STTR Survey Response Rates

| Total | |

| Total Awards |

1,501 |

|

Excluded from survey population |

101 |

| Preliminary target population |

1,400 |

| Not contactable |

807 |

|

Bad emails |

266 |

|

Bad phone |

518 |

|

Opt outs |

23 |

| Effective survey population |

593 |

| Completed surveys |

292 |

| Success rate (preliminary population) |

20.9 |

| Success rate (effective population) |

49.2 |

SOURCE: 2011-2014 Survey.

We concurred that this should be attempted. There is no simple and easy way to acquire a comparison group for Phase II SBIR/STTR awardees. These are technology-based companies at an early stage of company development, which have the demonstrated capacity to undertake challenging technical research and to provide evidence that they are potentially successful commercializers. Given that the operations of the SBIR-STTR programs are defined in legislation and limited by the Small Business Administration (SBA) Policy Guidance, randomly assigned control groups were not a possible alternative. Efforts to identify a pool of SBIR/STTR-like companies were made by contacting the most likely sources—Dunn and Bradstreet and Hoovers—but these efforts were not successful, because sufficiently detailed and structured information about companies was not available.

In response, the committee sought to develop a comparison group from among Phase I awardees that had not received a Phase II award from the three surveyed agencies (DoD, NSF, and NASA) during the award period covered by the 2011 Survey (FY1998-2007). After considerable review, however, we concluded that the Phase I-only group was not appropriate for use as a statistical comparison group, because the latter was not deemed to be a sufficiently independent control group.

Responses and Respondents

Table A-4 shows STTR responses by year of award. The survey primarily reached companies that were still in business—overall, 83 percent of respondents.12

________________

122011-2014 Survey, Question 4A.

TABLE A-4 STTR Responses by Year of Award (Percent Distribution)

| Fiscal Year of Award | STTR |

| 1998 | |

| 1999 |

0.7 |

| 2000 |

0.7 |

| 2001 |

4.8 |

| 2002 |

6.5 |

| 2003 |

5.5 |

| 2004 |

7.2 |

| 2005 |

14.4 |

| 2006 |

14.4 |

| 2007 |

19.2 |

| 2008 |

7.5 |

| 2009 |

7.2 |

| 2010 |

12.0 |

| Total |

100.0 |

| BASE: ALL RESPONDENTS |

292 |

SOURCE: 2011-2014 Survey.