A Research Agenda Toward Atmospheric Methane Removal (2024)

Chapter: 3 Why Consider Methane Removal?

3

Why Consider Methane Removal?

Climate action has many priorities for research and development, so it is necessary to consider carefully why researchers, industry, governments, and communities would research, develop, and/or deploy atmospheric methane removal technologies. Conceptual and technical arguments in support of and in opposition to the research and potential future deployment of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) and climate intervention approaches have been well documented (e.g., NASEM, 2019, 2021a, 2022a; NRC, 2015a,b). The Committee’s Statement of Task (see Chapter 1) specifically asks, “Why might atmospheric methane removal be needed?” This chapter begins to address this question by laying out potential high-level arguments in support of and in opposition to atmospheric methane removal and outlining specific potential use cases for atmospheric methane removal.

THE CASE FOR AND AGAINST METHANE REMOVAL

Greenhouse gas (GHG) removals—specifically CDR—have gained increasing traction as part of the climate response portfolio globally and in the United States and have reached a critical level of social investment by governments and private actors (see Chapters 1 and 2). Here, the Committee summarizes several example arguments that have been made in the literature by different actors or have emerged as narratives in favor of research, development, and/or deployment of CDR specifically and GHG removals more broadly that are relevant to the consideration of atmospheric methane removal:

- Emissions scenarios for policy and planning virtually all require GHG removals to meet 1.5°C and 2°C temperature targets (IPCC, 2023b).

- Countries should contribute to addressing climate change in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, including potentially through investment in technologies that could slow warming and avoid the most devastating impacts.1 Alongside emissions mitigation, GHG removals may help ameliorate the worst impacts of climate change for the most vulnerable communities.

- An equitable global energy transition may include the continued use of fossil fuels in particular geographic contexts or sectors, resulting in increased emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4). GHG removal technologies could compensate for these ongoing emissions.

- Perceived progress toward broad climate goals made via climate interventions could increase investments in mitigation (e.g., Cherry et al., 2023).

In approaching its task, the Committee identified potential high-level arguments “for” and “against” research and/or development of atmospheric methane removal. The Committee does not endorse any individual argument; instead, these wide-ranging considerations provide a useful conceptual framework explored in this and subsequent chapters.

High-Level Arguments Against Atmospheric Methane Removal

Trade-offs in time, resources, and climate impact have been central to debates over CDR and other climate interventions (e.g., solar geoengineering), and methane removal likely will face similar considerations. The nature of atmospheric methane, its sources, and the challenges of its removal further influence the consideration of this technology category. Possible arguments against research and/or development of methane removal include the following:

- Resources should be invested in activities that would have the greatest impact toward slowing climate change (i.e., methane and CO2 emissions mitigation). Furthermore, just as for CO2, methane emissions mitigation is cheaper than atmospheric methane removal technologies (see Chapter 5; Edwards et al., 2024).

- Methane removal could be used as an excuse not to mitigate existing sources (e.g., fugitive emissions from the oil and gas sector), and investments in research and development could take away resources from mitigation and adaptation.

- Unforeseen and/or unintended consequences may arise from deploying methane removal technologies.

- A risk of technological lock-in exists in which investments in atmospheric methane removal technologies could sustain investments in and maintenance of methane emitting infrastructure (e.g., coal mines, natural gas pipelines).

- The opportunity cost of investing in technologies may never materialize at scale.

___________________

1 Paris Agreement, Dec. 12, 2015, U/N. Doc. FCCC/CP/2-15/L.9/REv/1.

- The dilution of methane in the atmosphere and its chemical nature make removing methane technically and energetically challenging.

- Technology to remove methane at scale at atmospheric concentrations (2 parts per million [ppm]) is not currently available, and a risk of deploying immature technologies exists.

High-Level Arguments for Atmospheric Methane Removal

In addition to the general arguments in favor of GHG removals outlined at the start of this chapter, the Committee considered the unique ways in which atmospheric methane is contributing to climate change, thus making its removal attractive. Possible arguments in favor of research and/or development of atmospheric methane removal include the following:

- To achieve 50 percent reductions in anthropogenic methane emissions by 2050, atmospheric methane removal may be needed because the maximum technical potential for emissions reductions by 2050 is 45 precent (25–70%) (IPCC, 2023b).

- The short atmospheric lifetime and potency of methane as a GHG mean that unlike CO2 or nitrous oxide, the climate benefits of methane removal could be seen in both the short and long terms (see Chapters 1 and 2 and Figure 2-3).

- No emissions mitigation approaches currently exist for large natural sources of methane. Methane emissions from these natural sources are projected to increase due to climate warming, which would further exacerbate climate change. If natural methane emissions increase—not accounted for in policy planning scenarios—methane removal could be required.

- Removal of residual methane emissions that may not be addressed by currently available mitigation technologies may be needed to achieve GHG emissions reduction and temperature goals.

- Research on atmospheric methane removal could improve methane mitigation by helping to fill a technology gap—the lack of current technologies to mitigate methane below concentrations of ~1,000 ppm.

- Deployment of the hydrogen economy will lead to leakage of hydrogen that could increase the lifetime of atmospheric methane (due to competition between methane with hydrogen for reaction with hydroxyl radicals [OH]; see Chapter 5).

The Committee elaborates on these and additional arguments for atmospheric methane removal throughout this chapter—as requested in the Committee’s charge (see Chapter 1)—and considered this context when approaching its technology assessment and recommendations in subsequent chapters.

WHY CONSIDER ATMOSPHERIC METHANE REMOVAL?

Once the Committee identified potential high-level arguments for and against atmospheric methane removal, it further identified and considered five specific use cases for which research and/or development of atmospheric methane removal could be considered: (1) to improve methane mitigation capabilities, (2) to respond to the potential for large increases in natural emissions, (3) to close the methane emissions gap, (4) to restore atmospheric and ecological health, and (5) to develop capabilities to recover and use atmospheric methane. The remainder of this chapter explores each use case in detail. The purpose of these use cases is to illustrate potential motivations for different actors to pursue research and/or development of atmospheric methane removal; the Committee is not endorsing a single use case as an answer to the overarching question of this section.

Improving Methane Mitigation

Mitigation technologies that oxidize methane operate at limited concentration ranges. Flaring, the most common emissions mitigation method, can sustain an open flame down to concentrations of ~45,000 ppm (4.5%) methane. Concentrations below this level do not allow methane to burn in the open air.

At concentrations below combustible methane, a family of commercial thermal and catalytic oxidizers function for methane concentrations as low as 1,000 ppm (U.S. EPA, 2015). Such oxidizers are used in numerous commercial applications, including oxidizing ventilation air methane (VAM) from coal mines (e.g., Li et al., 2015). Methane concentrations down to ~2,000 ppm can be oxidized using regenerative thermal oxidizers (RTOs), which typically heat a ceramic block to contact and oxidize methane and volatile organic compounds (U.S. EPA, 2015). However, RTOs typically require air temperatures of 1,000°C to function, particularly for methane concentrations in the low thousands of parts per million. Moreover, the lower the methane concentration in air, the likelier it is that an RTO supplements natural gas (methane) in the air stream to increase the temperature in the unit.

To oxidize methane at even lower temperatures or lower concentrations, catalysts (typically noble metals such as platinum) are added to RTO-like systems and are known as regenerative catalytic oxidizers (RCOs). Such systems tend to be more expensive than RTOs but operate at lower temperatures (e.g., ~400°C for RCOs compared with ~1,000°C for RTOs) (U.S. EPA, 2015). RCOs can oxidize methane down to even lower concentrations of ~1,000 ppm methane in commercial applications (Stolaroff et al., 2012).

Microbial reactors are another commercial technology capable of oxidizing methane at relatively low concentrations (La et al., 2018). Microbial reactors have been used at landfills, at wastewater treatment plants, and—like RTOs—at coal mines for oxidizing VAM (e.g., Khabiri et al., 2022; Limbri et al., 2014; Ménard et al., 2012). The current lowest methane concentration oxidized by a microbial reactor commercially is ~1,000 ppm (Khabiri et al., 2022; La et al., 2018). However, laboratory and modeling

studies suggest that methane reactors could operate down to 500 ppm methane or below by optimizing reactor design and microbial affinities for methane (He et al., 2023; Yoon et al., 2009).

Despite decades of research to mitigate methane emissions, to the Committee’s knowledge, no commercial technology operates regularly below 1,000 ppm methane. This technology gap is critical to close because most methane emissions are found at concentrations below this threshold and, in fact, closer to ambient (~2 ppm) levels (see Chapter 2, Figure 2-1). Abernethy et al. (2023) estimated that most methane emitted globally from both natural and anthropogenic sources occurs at concentrations less than 10 ppm (∼400 teragrams [Tg] CH4 yr−1) (see Figure 3-1). This methane quickly dilutes to concentrations in background air, meaning that methane removal technologies operating at atmospheric methane concentrations (2 ppm) likely would be necessary to oxidize these emissions. Another ~5,300 Tg CH4 in the bulk air globally at concentrations of ~2 ppm could, in principle, be oxidized using methane removal technologies. Removal of ~3,200 Tg CH4 would restore the atmosphere to preindustrial methane levels of ~750 parts per billion and eliminate about 0.5°C of warming (IPCC, 2021; Jackson et al., 2019) (see Atmospheric and Ecological Restoration).

Pursuing research on methane removal at 2 ppm atmospheric methane concentrations could lower the limit of concentrations that can be addressed through currently available mitigation technologies, potentially expanding opportunities for reducing methane emissions from more sources.

Conclusion 3.1: At least 500 teragrams of methane per year are emitted below ~1,000 parts per million, the approximate concentration threshold marking the current limit of today’s mitigation technologies.

![Methane emission sources by concentration and quantity. The mass of methane theoretically available for oxidation at a given concentration (parts per million [ppm]) (left) and the same data in cumulative form where each point on the curve indicates the mass of methane emitted above a given concentration (right). Point sources are in red/orange, and area sources are in blue (though livestock can also be considered an area source). “Other” includes oceans, permafrost, geological seeps, biomass and biofuel burning, termites, and wild animals](https://uwnxt.nasx.edu/read/27157/assets/images/img-79-1.jpg)

SOURCE: Abernethy et al. (2023).

Potential for Large Increases in Natural Methane Emissions

In addition to challenges in reaching anthropogenic methane emission reduction targets, increases in methane emissions from natural sources magnified by climate warming may warrant the consideration of atmospheric methane removal. Natural methane-climate feedback processes—including amplified emissions from global wetlands, permafrost soils, and natural geologic sources—are likely to result in a steady but gradual rise in atmospheric methane emissions that could counteract anthropogenic mitigation efforts. While uncertainties exist in the magnitude and timing of these methane-climate feedbacks, a sudden or catastrophic release of large quantities of methane is not currently anticipated. Below, the Committee considers the projected changes in three natural methane-climate feedbacks that could inform the consideration of atmospheric methane removal.

Wetlands comprise the largest fraction of natural methane emissions in the present-day budget (159 [119–203] million tonnes [Mt] CH4 yr-1) (Saunois et al., 2024). Most wetland emissions originate in the tropics (62–77%). Climate warming and wetting is expected to increase tropical wetland emissions not only due to higher concentrations of atmospheric CO2—leading to higher wetland plant productivity, which in turn supplies substrates to microbes living in anoxic soils—but also due to warmer temperatures, which increase metabolic rates and precipitation that lead to the expansion of inundated soil areas. Some studies attribute the recent 2021–2023 growth in atmospheric methane concentrations to climate-driven increases in tropical wetland emissions (see Chapter 2).

Wetland ecosystems comprise a large fraction of the land surface in the Arctic because perennially frozen soils (permafrost) lead to water pooling above the permafrost table that creates anoxic conditions in near-surface soils. Ongoing climate warming and associated permafrost degradation has led to widespread drying of Arctic soils during recent decades (Liljedahl et al., 2016; Webb et al., 2022). This trend, which reduces wetland environments and facilitates natural methane uptake by soil microbes, may continue as climate warms in the future (Oh et al., 2020; Voigt et al., 2023). Thus, future increases in wetland emissions are expected mainly from the tropics. An offset to reductions in Arctic wetland emissions could be an increase in upland permafrost-thaw methane emissions in the same high-latitude regions. Contrary to previous expectations, large methane emissions have been discovered in well-drained upland permafrost soils where seasonal surface-freeze no longer extends down to the top of the permafrost table (Walter Anthony et al., 2024). Development of these perennially unfrozen soil layers, termed “taliks,” results in annual methane emissions three times higher than northern wetlands on an aerial basis (Treat et al., 2018). This discovery has important implications for permafrost-methane feedbacks to climate warming because until now, upland soils have been considered a methane sink (boreal forest) or insignificant methane source (tundra) (Kuhn et al., 2021). Model projections for future wetland increases have large uncertainties, but the projected increase (20–80 Mt yr-1 above their baseline by 2050; Kleinen et al., 2021) may be gradual rather than a burst in emissions over a short time period. Talik development in upland permafrost, a phenomenon that is expected to

accelerate this century (Farquharson et al., 2022; Parazoo et al., 2018), is likely to lead to further, unaccounted for methane emissions (Walter Anthony et al., 2024).

A well-known source of atmospheric methane in the Arctic is thermokarst lakes. In ice-rich permafrost regions, ground ice melt on the local scale results in ground subsidence and pooling of water that can form thermokarst lakes that accelerate the thaw and mineralization of permafrost soil organic carbon. Methane escapes lakes by bubbling that bypasses oxidation in the water column. Models project an acceleration of thermokarst-lake formation in the 21st century and associated emissions of methane from anaerobic mineralization of thawed permafrost soil organic matter (Schneider von Deimling et al., 2015; Walter Anthony et al., 2018). In some regions, such as interior Alaska, lake area has increased nearly 40 percent due to climate warming since the 1980s (Walter Anthony et al., 2021). Twenty-first century warming under the highest emissions scenarios projects an increase in methane emissions from thermokarst lakes by 15–50 Mt yr-1 through the formation of new lake areas that effectively thaw near-surface permafrost (Schneider von Deimling et al., 2015; Walter Anthony et al., 2018)—a scale that could cancel out some anthropogenic methane emissions reductions.

A third potential methane-climate feedback is the release of geologic methane from permafrost regions originating from leaky hydrocarbon reservoirs (e.g., coal beds, natural gas deposits, ancient sedimentary basins) and/or destabilized hydrates as permafrost thaws (Sullivan et al., 2021). Permafrost, glaciers, and ice sheets are considered impedances to the release of geologic methane (Kleber et al., 2023; Lamarche-Gagnon et al., 2019; Walter Anthony et al., 2012). The cumulative magnitude of the geologic methane pool is uncertain but is thought to exceed the atmospheric methane burden by two to three orders of magnitude, implying that even a fractional increase in geologic emissions could have catastrophic impacts on climate (Collett et al., 2011; Gautier et al., 2009; Isaksen et al., 2011; McGuire et al., 2009).

However, natural geologic methane emissions in the Arctic today are small (> 2 Mt yr-1) (Walter Anthony et al., 2012), and paleoclimate records indicate that past climate warming and permafrost degradation and retreat across the Arctic did not lead to perturbations in the atmospheric methane budget (Petrenko et al., 2017). The catastrophic release of geologic methane from permafrost is also unlikely this century because natural gas reservoirs are often trapped hundreds of meters below frozen ground. Rather, deep permafrost thaw affecting widespread geologic methane release is projected to occur over much longer timescales (centuries to millennia) (McGuire et al., 2009; Romanovsky et al., 2010; Ruppel, 2011). Massive release of methane from hydrate destabilization in marine continental margins has been suspected from abrupt warming of the Gulf of Guinea associated with a brief episode of meltwater-induced weakening of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation during the penultimate interglacial warming (126,000 to 125,000 years ago) (Weldeab et al., 2022). Such a response raises the possibility of new catastrophic methane releases from marine continental margins if ocean circulation were to change abruptly in the future.

Considering these natural methane-climate feedbacks together, based on estimates from modeling studies, a gradual 28 to 110 Mt CH4 yr-1 increase in natural wetland and thermokarst lake–sourced emissions is projected this century (24–97 Mt CH4 yr-1

during 2020–2050 due to a later [2065] peak in lake emissions) in response to climate warming (Kleinen et al., 2021; Schneider von Deimling et al., 2015). Methane release associated with talik development in permafrost uplands will likely increase this estimate further (Walter Anthony et al., 2024). This projected change in emissions would be a potentially strong headwind against the 180 Mt CH4 yr-1 reduction by 2030 needed to limit global climate warming to 2°C above preindustrial levels (UNEP & CACC, 2021). Atmospheric methane removal considered in this scenario would need to match the scale and duration of emissions from these methane-climate feedbacks to compensate for this rise in natural emissions. Furthermore, abrupt changes—for example, changes in ocean circulation leading to localized warming and destabilization of marine continental margin hydrates—represent an uncertain future scenario, and, unlike some anthropogenic sources, these natural methane-climate feedbacks cannot be turned off easily once invoked.

Closing the Methane Emissions Gap

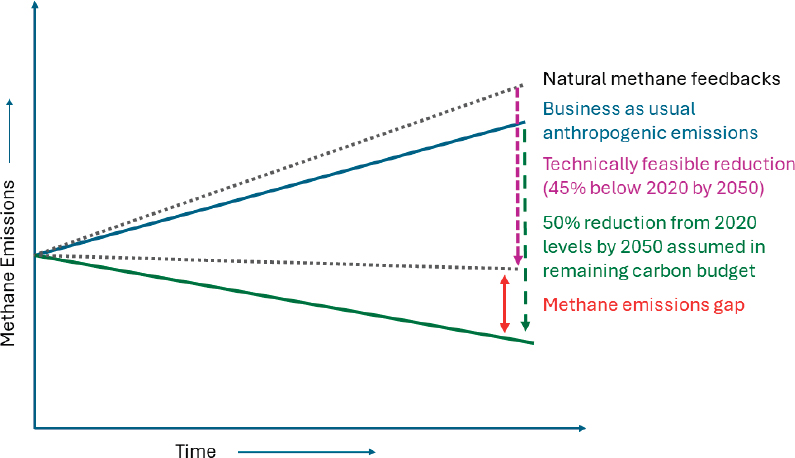

The potential for a “gap” between the methane emissions reductions needed to limit peak warming and stabilize climate and the technical potential for methane emissions mitigation is another potential use case for considering atmospheric methane removal. This potential “methane emissions gap” has two components: the technical limitations for mitigation of anthropogenic methane emissions, in particular residual emissions from the agricultural sector, and anticipated increasing emissions from natural methane sources that could exacerbate the gap. Figure 3-2 shows a qualitative representation of the “methane emissions gap” in which the emissions reductions required under a baseline scenario exceed the maximum technical potential for reducing anthropogenic methane emissions (45% by 2050 compared with 2020 levels) (IPCC, 2023b).

Pathways that limit end-of-century warming to 1.5°C with limited overshoot achieve net-zero CO2 emissions by mid-century and reduce anthropogenic methane emissions by 35 (standard deviation: ±10) percent in 2030, 46 (±8) percent in 2040, and 53 (±8) percent in 2050 relative to 2020 levels (Riahi et al., 2023; UNEP & CACC, 2022). Consistent with these reductions, the 2023 remaining carbon budget assumes a reduction of 51 (range 47–60) percent in methane emissions by 2050 relative to 2020 and no increase in natural methane emissions (Forster et al., 2023; Rogelj & Lamboll, 2024). Assuming 2019 anthropogenic emissions levels of 380 Mt CH4, this would imply a reduction of 130 Mt by 2030, 167 Mt by 2040, and 201 Mt by 2050, assuming no growth in anthropogenic emissions. However, Global Methane Assessment 2030: Baseline Report projects baseline growth in anthropogenic emissions between 2020 and 2030 of 25–40 Mt CH4 yr-1 (UNEP & CACC, 2022), implying an increase on the order of 75–120 Mt CH4 by 2050 if emissions grew at the same rate. Thus, the reductions in anthropogenic methane emissions required would be even greater.

Critically, natural methane sources are also expected to increase in a warmer and wetter world (Nisbet et al., 2023), yet none of the pathways assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report consider growth in natural methane emissions (Kleinen et al., 2021). An additional 25–100 Mt CH4 yr-1 from

anthropogenically amplified natural emissions from wetlands and permafrost would further add to this methane emissions gap (Abernethy & Jackson, 2024) (see Figure 3-2; see preceding section).

Scenarios that limit warming to 1.5°C by 2100 with limited overshoot have residual emissions in 2050 of about 150–220 Mt CH4 (Reisinger & Geden, 2023). The agricultural sector, including ruminant emissions associated with enteric fermentation, makes up the majority of the residual anthropogenic emissions after considering economically and technically feasible methane mitigation. Technical interventions to reduce emissions from enteric fermentation show promise and are being researched actively. While behavioral changes, such as changes in human diets, could address some of these residual emissions, social and other barriers to these changes make significant residual emissions from the agricultural sector likely (e.g., IPCC, 2023b).

The conventional approach to addressing these residual emissions in the context of net-zero GHG emissions is to compensate for the residual methane emissions with CDR (e.g., Buck et al., 2023). Compensating for climate impacts from residual methane emissions with CDR, especially in the near term, however, would require rates of CDR that “might be too high to be feasible,” up to 5.5 Gt CO2 yr-1 by 2025 and 12.8 Gt CO2

yr-1 by mid-century (Brazzola et al., 2021) compared to current CDR of 2 Gt CO2 yr-1 (Smith et al., 2024). Lamb et al. (2024) identified a CDR “gap” of 0.4–5.5 Gt CO2 yr-1 by 2050 (compared to 2020) to limit warming to 1.5°C. While most global warming impact metrics seek to equate a level of non-CO2 emissions with a CO2 warming equivalent, Brazzola et al. (2021) illustrate the challenge of compensating for the near-term warming impacts of methane by requiring an infeasible level of CDR and the limitations of treating CO2 and potent short-lived climate pollutants as fungible.

This methane emissions gap would be increased further if hydrogen or carbon monoxide emissions increased—for example, from the expansion of the hydrogen economy—resulting in reduction in the oxidative capacity of the atmosphere and extending the lifetime of methane (Bertagni et al., 2022; Ocko & Hamburg, 2022; T. Sun et al., 2024; Warwick et al., 2023) (see Chapter 5). Large-scale adoption of e-methane (synthetic methane ideally generated from green hydrogen and captured CO2) could also add to the methane emissions gaps if the e-methane supply chain is not strictly low-emissions along its supply, transport, and distribution. Furthermore, the Renewables Fuel Standard (RFS) in the United States provides a cautionary example of the need for strong regulatory measures to ensure that higher-cost technologies (such as cellulosic ethanol in the case of the RFS and green hydrogen in the case of e-methane) are successful in displacing the lower-cost and more climate-damaging incumbent technologies (Lark et al., 2022).

To account for this potential methane emissions gap accurately in policy and planning decisions, it would be useful to account for methane and long-lived GHGs like CO2 separately (e.g., Allen et al., 2022; Pierrehumbert, 2014). This is especially important when seeking to limit near-term and longer-term warming simultaneously (Dreyfus et al., 2022; Miller et al., 2024). Furthermore, differences in warming impacts between methane and CO2 imply non-fungibility of methane and CO2, which is a common assumption in voluntary and compliance carbon markets. While these markets likely will be relied upon more often as governments and industries look for ways to meet their net-zero goals, the assumptions and efficacy of these mechanisms require further scrutiny (see Chapter 5).

Conclusion 3.2: There will likely be a substantial methane emissions gap between the trajectory of increasing methane emissions (including from anthropogenically amplified natural emissions) and technically available mitigation measures, impeding emissions reductions needed to limit peak warming. The scale of carbon dioxide removal required to compensate for these residual methane emissions may not be feasible. Furthermore, it may not be appropriate to treat carbon dioxide and methane emissions reductions or compensatory removals as fungible, particularly for considering climate impacts in the near term.

The intent of utilizing atmospheric methane removal in this scenario would be to limit global average temperatures. Thus, the scale of atmospheric methane removal would need to approach tens of million tonnes per year to compensate for the methane emissions gap and the magnitude of potential anthropogenically amplified natural

emissions (Abernethy et al., 2021; see previous section). The duration of atmospheric methane removal would need to match the scale and duration of the methane emissions gap to stay within global temperature goals.

Atmospheric and Ecological Restoration

The concept of atmospheric restoration via climate interventions has been proposed (Jackson & Salzman, 2010) as an extension of ecological restoration—repairing the atmosphere in the same spirit that we repair disturbed or damaged ecosystems. Different atmospheric methane removal technologies could potentially advance the goals of atmospheric and ecological restoration. Reductions in atmospheric concentrations of methane via mitigation or removal slow the rate and magnitude of global temperature increases (see Chapter 2). Additionally, while methane and CO2 emissions mitigation and CDR address historical and continued anthropogenic emissions, they do not address increasing methane emissions from natural sources (see previous sections); atmospheric methane removal holds the potential to restore atmospheric methane concentrations to preindustrial levels (Jackson et al., 2019). At the same time, potential undesired or unintended consequences of atmospheric methane removal technologies, especially in the case of open system approaches, would need to be assessed carefully and considered in the context of the goal of restoration (see Chapter 5). The twin examples of ozone and methyl chloroform demonstrate that restoring atmospheric levels of globally well-mixed GHGs is plausible and that co-benefits of emissions reductions can increase the viability of such efforts.

One demonstrated example of modern atmospheric restoration is the recovery of the ozone layer from phasing-out production and consumption of ozone-depleting substances (e.g., chlorofluorocarbons) through universal global adoption of the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (see Silverman-Roati & Webb, 2024). Atmospheric ozone levels are on track to recover to 1980 levels by roughly mid-century (WMO, 2022), though this recovery has had setbacks (Western et al., 2023). With full implementation of the Montreal Protocol and recovery of the ozone layer, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that Americans born between 1890 and 2100 are expected to avoid 443 million cases of skin cancer, approximately 2.3 million skin cancer deaths, and more than 63 million cases of cataracts, with far greater benefits worldwide (Madronich et al., 2021; U.S. EPA, 2020).

Methyl chloroform, or 1,1,1-trichloroethane (CH3CCl3), provides the strongest example of atmospheric restoration to date (Jackson, 2024). Methyl chloroform is important for studies of the global methane cycle; its only significant atmospheric sources are from industrial emissions, and it is useful as an indicator of OH abundance in the troposphere (Lovelock, 1977). Until the Montreal Protocol banned its production in 1996, methyl chloroform was widely used as an industrial solvent, cleanser of circuit boards and photographic films, degreaser, adhesive, and insect fumigant and for many other applications. It has an atmospheric lifetime of approximately 6 years, roughly half the perturbation lifetime of methane. Emission cuts therefore lead quickly to decreased atmospheric concentrations of methyl chloroform, as they would for methane. The

global concentration of methyl chloroform peaked at ~140–150 parts per trillion (ppt) around 1992 before falling to today’s value of <1 ppt (Rigby et al., 2017). The atmospheric concentration of methyl chloroform today is so low (i.e., near the detection limit) that methyl chloroform is losing its utility as a tracer of OH abundance.

In addition to the potential for atmospheric restoration, atmospheric methane removal—specifically through the enhancement of methane uptake primarily in managed ecosystems—could have the co-benefits of land restoration and improvement of ecosystem services that could lead to ecological restoration. Many areas with high methane emissions overlap with areas that have historically undergone or are currently undergoing land use changes (e.g., from agriculture) or other types of degradation (e.g., from resource extraction or natural phenomena). The global area of degraded land is estimated to be on the order of 12.16 million km2 (Gibbs & Salmon, 2015), and from 1990 to 2015, an increasing rate of anthropogenic land use change has led to the loss of 1.6 million km2 of pristine land (Theobald et al., 2020). As land has transformed for human use, methane emissions have increased and methanotrophic capacity has declined (McDaniel et al., 2019). These areas may hold the potential to enhance natural methane sinks that have been disrupted by land use changes.

For example, land restoration involving reforestation or afforestation has been successful for recovering soil methanotrophic activity (De Bernardi et al., 2022; Gatica et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023), even reaching methane consumption rates not far from previous pristine conditions (McDaniel et al., 2019). Furthermore, plant surfaces frequently sustain methanotrophic microbes (Gauci et al., 2024; Iguchi et al., 2012; Jeffrey et al., 2021; Yoshida et al., 2014). While studies of tree canopy methane fluxes show that they can act as sources or sinks of methane (Gorgolewski et al., 2023; Halmeenmäki et al., 2017; Pangala et al., 2017; Putkinen et al., 2021; Sundqvist et al., 2012), canopy measurements of certain tree species have shown that they can also act as methane sinks (Putkinen et al., 2021; Sundqvist et al., 2012); this suggests that reforestation or afforestation could have the co-benefits of enhancing methane sinks and restoring certain degraded land.

The legacy effects of land use (e.g., nitrogen and other nutrients, soil structure, or carbon quality) can have variable effects on methane dynamics, increasing or decreasing soil methane consumption or overall flux (Kim et al., 2021; Lage Filho et al., 2023; Rosace et al., 2020). Nitrogen deposition tends to decrease methanotrophy (K.-H. Chen et al., 2024; Li et al., 2021); thus, nitrogen-driven legacy effects could have a similar effect. Denitrifying methanotrophs can further remove methane formation in anoxic layers, and nitrogen-driven legacy effects would enhance this role (J. Wang et al., 2023; Xia et al., 2020).

Another example of land restoration efforts is the U.S. Department of Agriculture Grassland Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) (see Chapter 2). While CRP does reduce emissions, it has not yet been quantified whether CRP enhances net GHG removal since it will be ecosystem-dependent. CRP provides multiple benefits, including retaining carbon in various forms; perhaps atmospheric methane removal could be a co-benefit, but this has not yet been explored or quantified.

Recovery and Use of Atmospheric Methane

The technical challenges of recovering or utilizing ~2 ppm atmospheric methane as a source of fuel or value-added product mean that it is not a currently feasible use case of atmospheric methane removal technologies (see Chapter 4). However, higher-concentration methane generated from the energy, waste, and agricultural sectors is already being utilized as a fuel source, most notably as renewable natural gas (RNG). For completeness, this section summarizes current practices for the recovery and use of high-concentration methane in the energy, waste, and agricultural sectors, which could be relevant to atmospheric methane removal should breakthrough technological advances emerge.

RNG is anaerobically generated biogas that is refined for use in place of fossil natural gas. In the United States, the main sources of biogas used to produce RNG are municipal solid waste landfills, municipal water resource recovery facilities, livestock farms, and stand-alone organic waste management operations (U.S. EPA, 2024a). Globally, almost half of biogas production is based in Europe, followed by China (21%), the United States (12%), and India (9%) (IEA, 2023a). The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that global biogas production will accelerate over 2023–2028, primarily in Europe and North America, due to new policies (IEA, 2023a). For example, U.S. EPA’s new Renewable Fuel Standard rule aims to double biomethane supplies from 2023 to 2025 (U.S. EPA, 2023a). According to the IEA’s Net Zero Scenario, production of biogases should quadruple by 2030.

The ability to use recovered methane as a fuel source is dependent on the concentration and quality of the methane generated at the source and on the desired end use. Technologies exist to recover and use methane at concentrations as low as 1,500 ppm; however, enrichment of the methane source (i.e., higher concentrations) would be necessary for energy production at lower concentrations. Methane in waste gases has historically been challenging to valorize in the oil and gas sector and other sectors due to issues with the quality (e.g., high levels of dilution; presence of contaminants, like hydrogen sulfide), low commodity prices, isolated locations requiring trucking, and sites with limited or no access to power. Other barriers to methane recovery and use include market barriers; access to gas or electricity networks; and, in the case of coal mines, property rights.

The main source of RNG in the United States is landfill gas (LFG), produced from the decomposition of organic wastes generating CO2, methane, and other non-methane compounds. The current U.S. EPA GHG inventory estimates that 4.3 Tg CH4 was generated from landfills in 2022 (U.S. EPA, 2024b). LFG is approximately 50–55 percent methane, and the technology to recover LFG is in operation (Chetri & Reddy, 2021). Once LFG is moved to a point where it can be processed, LFG can be flared (which in the United States is legally required), used for electricity production, used directly for heating, or upgraded to pipeline-quality natural gas. U.S. EPA’s Landfill Methane Outreach Program works cooperatively with industry and waste officials to reduce or avoid methane emissions from landfills. It estimates that as of 2022, 535 active projects have direct emission reductions of approximately 27.8 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent

(U.S. EPA, n.d.a). The major technical challenges in recovery and use of LFG are the unpredictability of the methane generation rate, the occasional low methane production, and the high amount of trace components (Chetri & Reddy, 2021). Additional barriers to LFG use include financial barriers related to the capital investment, lack of connection to gas and electricity networks, and solid waste management practices. These barriers at high methane concentrations in LFG would be magnified for low concentrations of atmospheric sources of methane.

Livestock manure also generates methane (~2.3 Tg in the United States) via the anaerobic decomposition of organic matter. In production systems where animals are concentrated and manure is stored as a liquid or slurry (most commonly in dairy and swine production), methane may be produced. Methane can be captured by covering manure storage, and the use of anaerobic digesters can enhance methane generation from manure. In both instances, methane can be upgraded and utilized as a fuel to generate electricity or as RNG. As of January 2023, there were 343 anaerobic digester projects on livestock farms in the United States. In 2022, manure-based anaerobic digesters resulted in 0.35 Tg of direct methane reductions (U.S. EPA, n.d.b). Similar to LFG use, barriers include the large capital investment for building digesters or covering manure stores as well as upgrading the gas and lack of access to gas and electricity networks.

Another source of methane that is currently recovered and utilized is coal mine methane, which is released during coal mining activities. This methane must be removed from underground mines to prevent explosive hazards, typically through ventilation and drainage systems. Abandoned mines may continue to produce methane after mining activities have ceased. In 2015, it was estimated that approximately 1.78 Tg (66% of total U.S. coal mining emissions) of methane was emitted via ventilation in the United States (NASEM, 2018). These ventilation systems produce large amounts of dilute methane (typically <1,000 ppm), comprising the largest source of methane from coal mining. Technology has progressed to the point at which VAM can, under some conditions, be converted to useful forms of energy used to produce heat, electricity, or refrigeration (U.S. EPA, 2003, 2019). U.S. EPA’s Coalbed Methane Outreach Program (CMOP)2 aims to work with the coal mining industry to reduce coal mine methane emissions voluntarily through recovery and use projects. Australia has a similar federally funded research program (Resources Methane Abatement Fund, Department of Industry, Science and Resources).3 As of January 2023, U.S. EPA’s CMOP is aware of 25 coal mine methane projects at 16 active mines and another 35 abandoned coal mine methane projects at 66 abandoned (closed) mines (U.S. EPA, n.d.c). It estimated that methane emissions were reduced by 0.28 Tg in 2021, with a cumulative reduction of approximately 8.4 Tg since 1994. From a research perspective, improving understanding of the fluctuations in methane concentrations and emissions from mines could make a more compelling case to mine operators and project developers about the technical and economic potential for these conversion projects (see Chapter 6).

___________________

2 See https://www.epa.gov/cmop.

3 See https://business.gov.au/grants-and-programs/resources-methane-abatement-fund.

Technologies to capture and either oxidize methane or utilize it as an energy source are operational and used in the fossil fuel, waste, and agricultural sectors where methane concentrations are high. In the context of this report, these technologies are considered to be mitigation strategies as they prevent methane from entering the atmosphere at the source. The technologies described here are generally sufficient to see adoption of methane use, mitigation, or recovery from these sectors, with supportive policies, markets, and other local contexts. These same conditions would also be needed for atmospheric methane recovery to be technically and economically viable. Recovery and use of atmospheric methane at low (~2 ppm) concentrations is much more difficult, and the ability to scale to a level that would have climate-relevant impact is unlikely.

This page intentionally left blank.