Bridge Railing Design Requirements (2024)

Chapter: 2 Literature Review

CHAPTER 2

Literature Review

Scope

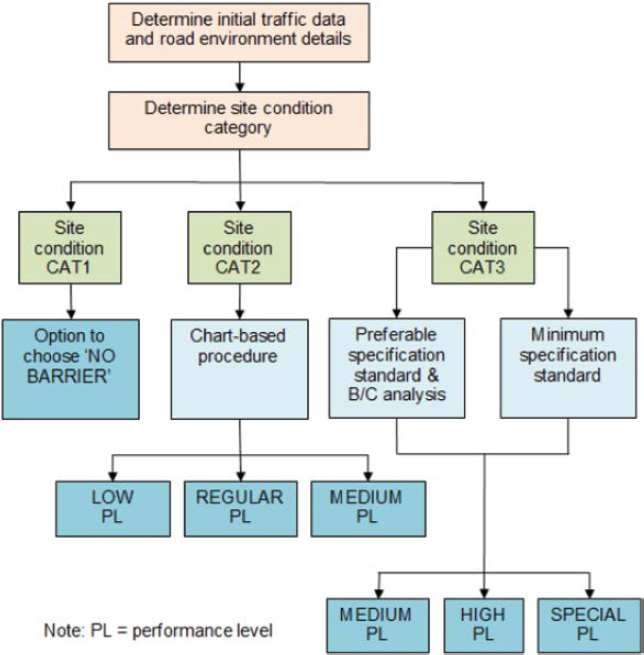

This review considered the state of the practice in the testing, design, and evaluation procedures for bridge rail systems. For this review, the current AASHTO LRFD BDS (AASHTO 2020a) was considered to be the state of the practice; research in the roadside safety community not included in the current AASHTO LRFD BDS is considered to be the state of the art. Research efforts identified in this review include but are not limited to (1) full-scale crash tests demonstrating MASH-compliant systems, (2) guidelines and alternative methods for the design of bridge rail systems, and (3) guidelines and alternative methods for the design of bridge deck overhangs. Priority is placed on domestic literature, with particular emphasis on NCHRP reports, NCHRP projects, and literature published in the Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board.

After the initiation of this research project, NCHRP Project 12-119, “MASH Railing Load Requirements for Bridge Deck Overhang” (Steelman et al. 2023) was initiated and completed to investigate bridge overhang design with AASHTO MASH test criteria. That work is reported separately and is not part of the literature review in this chapter.

Comparison of NCHRP Report 350 to MASH 2016 Criteria

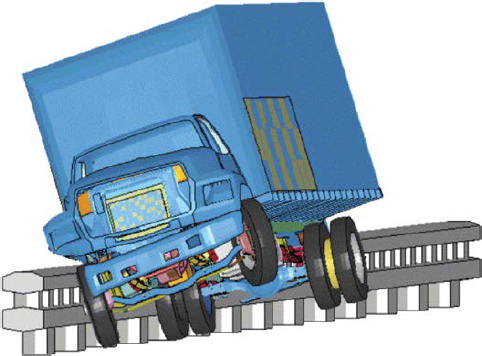

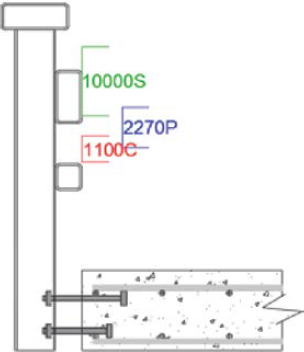

The conversion from NCHRP Report 350 (Ross et al. 1993) to MASH 2016 (AASHTO 2016) is accompanied by significant changes to vehicle characteristics and impact conditions. With the goal of representing the 85th percentile crash severity, the implementation of MASH 2016 is characterized by heavier vehicles, higher speeds, and more severe impact angles. While some barriers deemed acceptable under NCHRP Report 350 may be grandfathered into MASH compliance (Silvestri-Dobrovolny et al. 2017), some once-adequate barriers will fail to meet MASH standards. For example, the NCHRP Report 350-approved 32-in. New Jersey safety shape was found to be inadequate under MASH Test Level (TL)-4 conditions by researchers at the Midwest Roadside Safety Facility (MwRSF) in a full-scale crash test, as demonstrated in Figure 1 (Polivka et al. 2006). Subsequent testing of the same system at the Texas A&M Transportation Institute (TTI) substantiated this finding (Bullard et al. 2010).

Note that for longitudinal barriers, the differences between the first edition of MASH (AASHTO 2009b) and MASH 2016 (AASHTO 2016) criteria are minimal. No changes were made to the test conditions or vehicle dimensions. Changes were focused on vehicle damage documentation, particularly regarding floor pan and undercarriage photography. As such, any longitudinal system meeting MASH 2009 criteria meets MASH 2016 criteria.

Changes to Test Vehicles

To reflect the ever-changing fleet of vehicles in use on the road, revisions to crash-testing standards often include updates to vehicle characteristics. From the standards of NCHRP Report 350 (Ross et al. 1993) to those of MASH 2016 (AASHTO 2016), both the passenger car and pickup truck test vehicles saw marked increases in their test inertial weights and overall dimensions. Notable changes include a 57% increase in the weight of the small passenger car, a 13% increase in the weight of the pickup truck, and the removal of the center of mass height requirement for the passenger car. Changes to key dimensions for the small passenger car and pickup truck are presented in Table 1.

The conversion from NCHRP Report 350 to MASH 2016 also imposed significant changes on the single-unit truck (SUT) test vehicle. Most notably, the SUT increased in weight by 25%. Changes to key dimensions of the SUT test vehicle are shown in Table 2.

Table 1. Changes to nominal characteristics of small passenger car and pickup truck.

| Vehicle Type | Testing Standard | Test Vehicle | Weight (lb) | Dimensions | Center of Mass Location | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Length (in.) | Track Width (in.) | Front Overhang (in.) | Behind Front Axle (in.) | Above Ground (in.) | ||||

| Small Passenger Car | NCHRP Report 350 | 820C | 1,808 | 146 | 53 | 30 | 31 | 22 |

| MASH 2016 | 1100C | 2,420 | 169 | 56 | 35 | 39 | NA | |

| Pickup Truck | NCHRP Report 350 | 2000P | 4,410 | 211 | 65 | 31 | 55 | 28 |

| MASH 2016 | 2270P | 5,000 | 237 | 67 | 39 | 63 | 28 | |

NOTE: The 820C car from NCHRP Report 350 and the 1500A sedan from MASH 2016 are excluded from this table; NA = not applicable.

Table 2. Changes to nominal characteristics for SUTs and tractor-trailer vehicles.

| Vehicle Type | Testing Standard | Test Vehicle | Weight (lb) | Dimensions | Height of Ballast Center of Mass (in.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Length (in.) | Trailer Overhang (in.) | Bed Height (in.) | |||||

| Single-Unit Truck | NCHRP Report 350 | 8000S | 17,637 | 343 | NA | 51 | 67 |

| MASH 2016 | 10000S | 22,046 | 394 | NA | 49 | 63 | |

| Tractor-Van Trailer | NCHRP Report 350 | 36000V | 79,300 | 780 | 87 | 52 | 73 |

| MASH 2016 | 36000V | 79,300 | 780 | 87 | 50 | 73 | |

| Tractor-Tank Trailer | NCHRP Report 350 | 36000T | 79,300 | 780 | NA | NA | 81 |

| MASH 2016 | 36000T | 79,300 | 780 | NA | NA | 81 | |

NOTE: NA = not applicable.

Unlike the lighter vehicles, the characteristics of the tractor-van trailer and tractor-tank trailer were left unchanged in the conversion. However, under the standards of NCHRP Report 350, it was common practice to use loose material, such as sandbags or hay bales, as ballast. Although the standards recommended that the ballast be firmly secured to the floor of the cargo box, arresting these materials completely would be virtually impossible. Consequently, the motion of the ballast material within the cargo box could reduce the impact loads imposed on the barrier by increasing the time interval over which the vehicle’s change in momentum occurs. In MASH 2016, sandbags and hay bales are still considered acceptable, but more rigid ballast materials, such as metal or concrete blocks, are also proposed. In recent practice, the use of portable concrete barriers as ballast material is common. As such, while the weights of the articulated test vehicles have been left unchanged in the conversion, the impact forces associated with these vehicles require attention nonetheless and are discussed in Chapter 3.

Changes to Test Conditions

In addition to test vehicle modifications, the implementation of MASH 2016 is also accompanied by changes to the impact conditions of tests required for the evaluation of bridge rails. The nominal impact angle required in all small passenger car tests increased from 20 degrees to 25 degrees, and the nominal impact speed required in the SUT test increased from 50 mph to 56 mph. When combined with increases in vehicle weights, these changes resulted in nearly universal, significant increases in the impact severity of full-scale crash tests. The impact severity (IS) associated with a test is equal to the lateral component of the vehicle’s kinetic energy:

| (1) |

wherein m is the vehicle mass (slugs), v is the vehicle’s initial velocity (fps), and θ is the impact angle. This parameter is a key metric in the evaluation of a full-scale crash test, as it quantifies the lateral impact energy that must be accepted and redirected by the barrier. When evaluating the testing procedure from a designer’s perspective, the IS of an impact is roughly analogous to lateral impact force—higher IS values indicate higher lateral forces exerted on the barrier. Changes to the testing matrices relevant to bridge rail systems are collected in Table 3. Except for articulated vehicle tests 5-12 and 6-12, nominal IS values increased in all test designations.

Table 3. Comparison of NCHRP Report 350 to MASH 2016 test conditions for longitudinal barriers.

| Test Level | Test No. | Testing Standard | Test Vehicle | Vehicle Weight (lb) | Nominal Impact Conditions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed (mph) | Angle (degrees) | IS (kip-ft) | IS % Increase | |||||

| 1 | 1-10 | NCHRP Report 350 | 820C | 1,808 | 31 | 20 | 6.8 | — |

| MASH 2016 | 1100C | 2,420 | 31 | 25 | 13.9 | 104% | ||

| 1-11 | NCHRP Report 350 | 2000P | 4,410 | 31 | 25 | 25.3 | — | |

| MASH 2016 | 2270P | 5,000 | 31 | 25 | 28.7 | 13% | ||

| 2 | 2-10 | NCHRP Report 350 | 820C | 1,808 | 44 | 20 | 13.7 | — |

| MASH 2016 | 1100C | 2,420 | 44 | 25 | 28.0 | 104% | ||

| 2-11 | NCHRP Report 350 | 2000P | 4,410 | 44 | 25 | 51.0 | — | |

| MASH 2016 | 2270P | 5,000 | 44 | 25 | 57.8 | 13% | ||

| 3 | 3-10 | NCHRP Report 350 | 820C | 1,808 | 62 | 20 | 27.2 | — |

| MASH 2016 | 1100C | 2,420 | 62 | 25 | 55.5 | 104% | ||

| 3-11 | NCHRP Report 350 | 2000P | 4,410 | 62 | 25 | 101.2 | — | |

| MASH 2016 | 2270P | 5,000 | 62 | 25 | 114.8 | 13% | ||

| 4 | 4-10 | NCHRP Report 350 | 820C | 1,808 | 62 | 20 | 27.2 | — |

| MASH 2016 | 1100C | 2,420 | 62 | 25 | 55.5 | 104% | ||

| 4-11 | NCHRP Report 350 | 2000P | 4,410 | 62 | 25 | 101.2 | — | |

| MASH 2016 | 2270P | 5,000 | 62 | 25 | 114.8 | 13% | ||

| 4-12 | NCHRP Report 350 | 8000S | 17,637 | 50 | 15 | 98.7 | — | |

| MASH 2016 | 10000S | 22,046 | 56 | 15 | 154.8 | 57% | ||

| 5 | 5-10 | NCHRP Report 350 | 820C | 1,808 | 62 | 20 | 27.2 | — |

| MASH 2016 | 1100C | 2,420 | 62 | 25 | 55.5 | 104% | ||

| 5-11 | NCHRP Report 350 | 2000P | 4,410 | 62 | 25 | 101.2 | — | |

| MASH 2016 | 2270P | 5,000 | 62 | 25 | 114.8 | 13% | ||

| 5-12 | NCHRP Report 350 | 36000V | 79,300 | 50 | 15 | 443.9 | — | |

| MASH 2016 | 36000V | 79,300 | 50 | 15 | 443.9 | 0% | ||

| 6 | 6-10 | NCHRP Report 350 | 820C | 1,808 | 62 | 20 | 27.2 | — |

| MASH 2016 | 1100C | 2,420 | 62 | 25 | 55.5 | 104% | ||

| 6-11 | NCHRP Report 350 | 2000P | 4,410 | 62 | 25 | 101.2 | — | |

| MASH 2016 | 2270P | 5,000 | 62 | 25 | 114.8 | 13% | ||

| 6-12 | NCHRP Report 350 | 36000T | 79,300 | 50 | 15 | 443.9 | — | |

| MASH 2016 | 36000T | 79,300 | 50 | 15 | 443.9 | 0% | ||

NOTE: Cells with — have no data; the figures in these rows are the baseline values used to compare changes.

In small passenger car tests, IS increased by roughly 104%. In pickup truck tests, IS increased by 13%. In SUT tests, IS increased by 57%, increasing the nominal IS value for TL-4 bridge rails from 101.2 kip-ft to 154.8 kip-ft. As most bridge rails on major roadways are expected to meet TL-4 requirements, this increase in demand is particularly significant.

Impact Force Estimation Methods

The accurate estimation of impact demands is a key factor in the design of effective and efficient bridge rail systems. Low estimates may result in catastrophic structural failures or vehicle rollover events. Alternatively, high estimates may result in more expensive systems and overdesigned deck overhangs, imposing unnecessary stress on bridge owners’ budgets. Force estimates, then, provide an essential foundation for the design of any bridge rail system. However, the impact between a vehicle and a bridge rail system is an immensely complicated event. As a consequence of this intricacy, a wide variety of force estimation methods employing diverse philosophies and disparate levels of sophistication are currently used in practice. A singular, most accurate method has yet to be decided upon in the roadside safety community. The progression of impact force estimation methods, many of which still see use in contemporary applications, is demonstrated in the following sections.

Theoretical Methods

The oldest and lowest-resolution impact force estimation methods are those that attempt to idealize three-dimensional (3D) impact conditions and estimate the lateral impact force in a closed-form solution applicable to a two-dimensional (2D) space (a horizontal impact plane). As impact scenarios between vehicles and barrier systems are highly complicated, theoretical methods are likely the least accurate of the impact force estimation methods. However, they retain value for approximate validation of more complicated methods, are relatively simple to perform, and their use does not require specialized software or equipment. Unlike the more robust estimation methods, theoretical models cannot predict vertical impact forces.

Olson Method

In the early to mid-1900s, the bridge rail design process was largely performance-based, and detailed analyses were rare. The first rigorous mathematical model for estimating impact forces was proposed by Olson et al. (1970). By analyzing high-speed films of full-scale crash tests, the general behavior of an impacting vehicle was identified and modeled using basic principles of dynamics. The model relies on several assumptions necessary to represent the impact with closed-form solutions.

- Vehicle decelerations are constant throughout the impact scenario.

- Vertical and rotational vehicle accelerations are neglected.

- The lateral component of the vehicle velocity has been completely arrested at the instant the vehicle is parallel to the barrier.

- Vehicle snagging does not occur.

- Vehicle crush does not alter the location of the vehicle center of mass.

- The vehicle moves as a point mass with its entire mass collected at the vehicle centroid.

- Barrier flexibility may or may not be included in the model. Typically, concrete barriers are assumed to have zero flexibility.

- Tire-to-pavement friction forces are neglected.

- The barrier does not contain features with the propensity to produce significant abrupt vertical motion.

- With the application of these assumptions to the model, the average lateral impact force can be estimated. The idealized impact scenario is shown in Figure 2.

The lateral movement of the vehicle c.g. can be expressed as:

| (2) |

in which AL is the distance from the vehicle front end to the vehicle c.g. (ft), θ is the impact angle, B is one-half of the vehicle width (ft), and D is the lateral deflection of the barrier (ft). The time interval over which the vehicle becomes parallel to the system is estimated using the average lateral velocity (Vlat,avg), assuming the lateral velocity at parallel is equal to zero:

| (3) |

With the magnitude and time interval of the vehicle c.g. motion estimated, the average lateral deceleration of the vehicle can subsequently be estimated:

| (4) |

where Glat is average lateral vehicle deceleration (gs), alat is average lateral vehicle deceleration (ft/sec2), g is the acceleration due to gravity (ft/sec2), ∆Vlat is the change in lateral velocity (ft/sec), and g∆t is the time interval from impact to maximum lateral movement of the vehicle’s center of gravity.

From Equation 4, the average lateral and longitudinal impact forces can be estimated via basic principles of dynamics:

| (5) |

| (6) |

wherein W is the vehicle weight (kips), and μ is the estimated friction coefficient between the barrier and the vehicle. The frictional relationship between the lateral and longitudinal impact forces applies to all theoretical models presented herein.

Hirsch Modification to the Olson Method

In the wake of two 1976 bridge rail failures causing high-profile, multiple-fatality accidents, T.J. Hirsch developed a modification to the Olson method in 1978 (Hirsch 1978). Whereas the Olson method produced an estimate of the average lateral impact force, Hirsch sought an estimate for the maximum lateral impact force. To relate the average and peak lateral forces, Hirsch idealized the stiffness of both the vehicle and the barrier as a linear spring, resulting in a sinusoidal relationship between the impact force and the time after impact (Figure 3).

With this idealization, the relationship between the average lateral force estimated via the Olson method and the peak lateral force is obtained from trigonometric relationships.

| (7) |

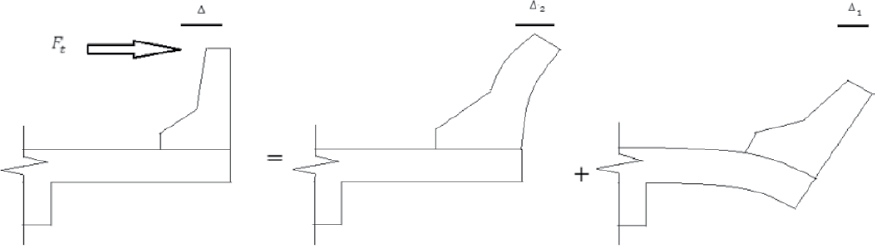

Impulse-Momentum Method

The most recent impact force estimation method relying only on a theoretical model is the impulse-momentum method first proposed by Ritter et al. (1993). In this method, it is assumed that the collision between the vehicle and the barrier is perfectly elastic. As such, the lateral velocity is mirrored across the barrier during impact; the final lateral velocity is equal to the initial lateral velocity but in the opposite direction. The lateral impulse exerted during the collision is equal to the change in lateral vehicle momentum during impact

| (8) |

wherein ρf,lat and ρi,lat are the final and initial lateral vehicle momenta, respectively (slug-fps), mv is the vehicle mass (slugs), vf,lat is the final lateral velocity (fps), vi,lat is the initial lateral velocity, and θ is the impact angle. The time elapsed between vehicle impact and the point at which the vehicle is parallel to the system is estimated via the Olson method. As such, the magnitude of the impulse and the time over which it occurs can be estimated. If a triangular force pulse is assumed (Figure 4), the relationship between the impact duration and peak lateral force is

| (9) |

which, when rearranged, provides an estimate for the peak lateral force:

| (10) |

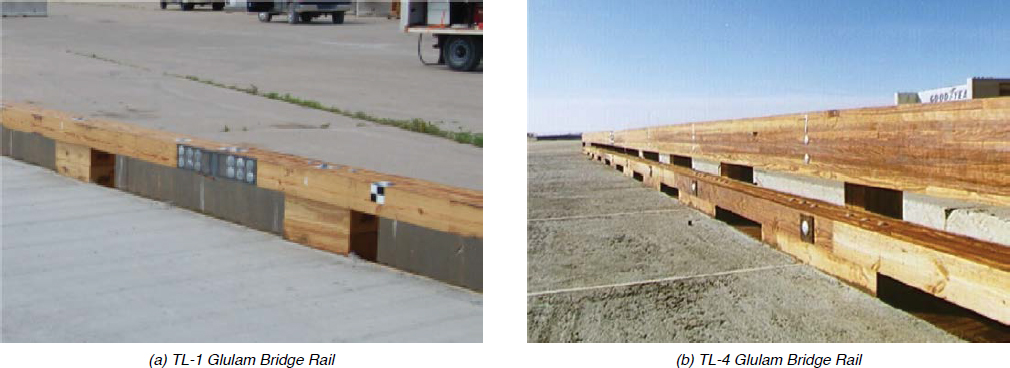

This method has seen use in multiple barrier design processes as a design load estimator (Ritter et al. 1993; Faller et al. 1996). Additionally, the method has been used to establish demand criteria to which an existing barrier system was evaluated (Loken et al. 2019). The results of this method can be obtained alternatively by increasing the dynamic factor of π/2 to 2 in Hirsch’s modification to the Olson method. Consequently, the impulse-momentum method will always provide the highest lateral impact force estimates of any theoretical model in the preceding discussion.

Computational Methods

Impact scenarios are characterized by a level of complexity that is virtually impossible to fully describe with simple mathematical relationships. Numerical methods, then, are far better suited to analyze vehicle impacts than theoretical methods. The finite element method has proven to be an invaluable tool in the design and analysis of roadside safety hardware under impact loading, though its use is often accompanied by extreme computational demands. For this reason, early computational methods employed low-resolution models with many simplifying assumptions. With the advancement of technology, however, high-fidelity modeling has not only become more practical but has come to define state-of-the-art methods in the roadside safety community.

BARRIER-VII

BARRIER-VII is a rudimentary 2D finite element analysis software developed in the 1970s to aid in the design of roadside safety hardware (Powell 1973). The software performs calculations with low-fidelity models (represented in Figure 5) to simulate impact conditions. Although the manifest purpose of BARRIER-VII is to evaluate the performance of a barrier under impact conditions, impact force estimates can be extracted from the simulation as cumulative lateral barrier forces over the impact area. While it is not a common method of force estimation, this method was employed by Bloom et al. in 1974 as part of an FHWA project to establish bridge rail guidelines (Bloom et al. 1974). In this application, the impact forces acting on concrete barriers

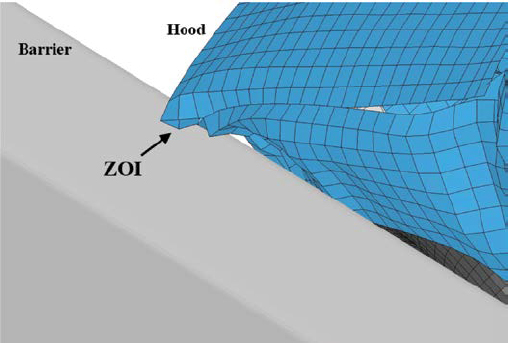

LS-DYNA

LS-DYNA is an advanced simulation tool produced by Livermore Software Technology Corporation in Livermore, California (Hallquist 2007). With nonlinear dynamic capabilities, LS-DYNA has proven to be a valuable tool for analyzing vehicle impact scenarios (Figure 6). As computing power becomes less expensive and more readily available, LS-DYNA is used more and more frequently within roadside safety applications. Currently, LS-DYNA represents the state of the art in collision simulation technology.

LS-DYNA sees extensive use in both the design and evaluation of bridge rail systems. Through advanced simulation in LS-DYNA, a system’s performance can be predicted prior to full-scale crash testing, resulting in better-informed and more successful tests. Impact force estimates can be extracted from these collision simulations in two ways: (1) direct measurement of contact forces between vehicle parts and the barrier system and (2) calculation of forces exerted by the

vehicle from measurements of the vehicle’s lateral, longitudinal, and rotational accelerations. The former of these methods allows for not only an estimate of the impact force magnitude but of the application location and footprint as well. To reduce noise, both extraction methods are commonly smoothed with a 50-ms averaging filter.

Whereas theoretical models are limited to lateral and longitudinal impact force estimates, LS-DYNA is capable of estimating vertical impact forces as well, using one of the two methods previously described. Additionally, LS-DYNA simulations are capable of capturing the effect of tail-slap, which occurs when the box of an SUT or articulated vehicle strikes a barrier. Lateral impact forces associated with tail-slap are typically more severe than those exerted in the initial impact sequence (Bligh et al. 2017). As such, accounting for tail-slap is important when estimating impact forces exerted by SUTs and articulated vehicles.

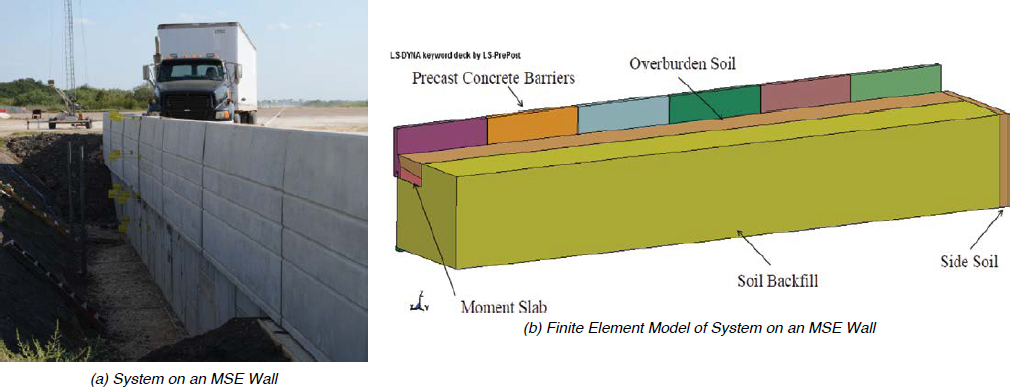

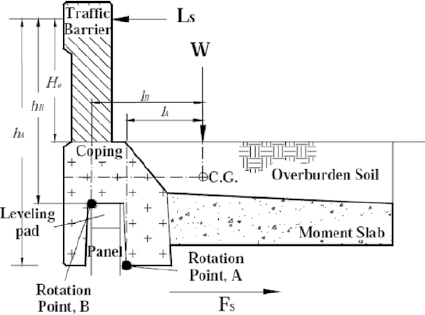

Several contemporary barrier studies have implemented LS-DYNA in their methodologies. In a research effort to propose guidelines for barriers installed on mechanically stabilized earth (MSE) retaining walls and updates to barrier design loads, Bligh et al. (2017) used LS-DYNA simulations to estimate the impact forces of MASH TL-4 and TL-5 test vehicles on concrete barriers of varying heights. Similarly, Silvestri-Dobrovolny et al. (2017) determined MASH equivalency of bridge rails approved under NCHRP Report 350 using impact forces extracted from LS-DYNA simulations. In both studies, impact simulations were used to form updated impact force estimates associated with MASH test vehicles. In these applications, impact forces were measured directly from part contacts and processed with a 50-ms averaging filter.

Measurement Methods

Theoretical and computational models estimate impact forces based on the mechanics, assumptions, and predictions of virtual impact scenarios. Conversely, impact forces can also be estimated via data collected in full-scale crash tests. In a full-scale crash test, impact forces can be estimated via direct measurement with an instrumented wall or calculated from measurements of the vehicle accelerations during the impact sequence.

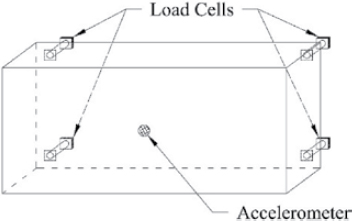

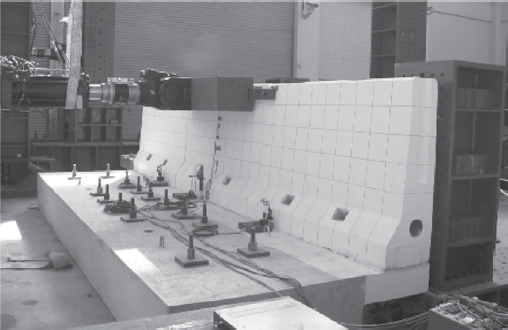

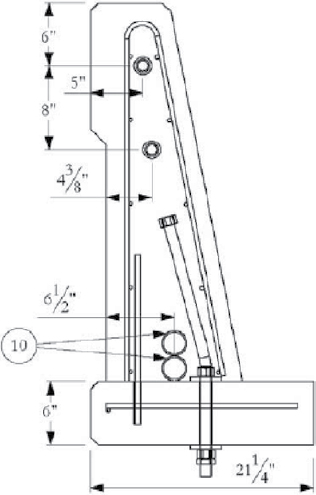

Instrumented Barrier

Impact forces can be measured in crash tests through the use of instrumented barriers. Barrier instrumentation types include load cells, accelerometers, and strain gages. In an instrumented wall test, load cells are installed on the nonimpact side of an impacted barrier to measure lateral impact forces exerted on the barrier. Additionally, instrumented walls are typically fastened with an accelerometer to account for inertial effects. A typical instrumented wall installation is shown in Figure 7.

Current design forces for bridge rails in AASHTO LRFD BDS were extracted from instrumented wall tests performed by Noel et al. (1981) and Beason et al. (1989). The studies featured

calibrated, instrumented concrete barriers subjected to a combined 18 full-scale crash tests of a variety of vehicles ranging from small passenger cars to a tractor-tank trailer. In both tests, results were passed through a 50-ms averaging filter to reduce data noise.

Instrumented walls represent a robust method of estimating impact forces. This method is capable of estimating a variety of pertinent impact conditions, such as impact force magnitudes, application heights, and vehicle-barrier contact area distributions. Additionally, instrumented wall tests are able to account for tail-slap effects. Instrumented wall tests, however, are expensive to perform and are typically unable to provide data on longitudinal or vertical impact forces. To expand the utility of instrumented wall test results, researchers derived relationships with which the results of an instrumented wall test could be extrapolated to other, noninstrumented crash tests. The relationship used to account for variations in conditions between tests, as described by Bligh et al. (2017), is demonstrated in Equation 11:

| (11) |

wherein Fi is the impact force, Vi is the impact velocity, θi is the impact angle, Li is the longitudinal distance from the front of the test vehicle to its c.g., Ki is the barrier contact area or stiffness, and Wi is the vehicle weight. Subscripts distinguish the impacts, with the parameters of the instrumented wall test denoted with subscript 1 and the impact with the desired conditions denoted with subscript 2.

Alternatively, impact forces can be measured indirectly through the use of strain gages. By securing strain gages to the reinforcing steel of a concrete barrier, impact forces can be calculated from deformations measured in the testing sequence.

Inertial Estimation

A more efficient, but less robust, alternative to the instrumented wall test is the vehicle-based inertial estimation method. Typically, in contemporary full-scale crash tests, an accelerometer is installed near the test vehicle’s c.g. to measure lateral, longitudinal, and vertical accelerations. Using the acceleration data from this instrument, rudimentary impact force estimates are derived from Newton’s second law of motion. However, due to the variation of mass, crush, and ballast character along the length of the vehicle, acceleration measurements may vary drastically at different locations within the vehicle. For this reason, if impact force estimates are to be derived from acceleration measurements, multiple accelerometers need to be installed along the vehicle length (Beason et al. 1989). As accelerations are sensitive to vehicle characteristics and mass distribution, the inertial estimation method differs between single-unit vehicles (like small passenger cars, pickup trucks, SUTs) and articulated, double-unit vehicles (like tractor trailers and tractor-tank trailers). To estimate the impact forces exerted by single-unit vehicles, Beason et al. (1989) installed two accelerometers along the vehicle length. The acceleration at the vehicle c.g. was linearly interpolated from the results of the two accelerometers. In the same study, articulated vehicles were treated as two single-unit vehicles connected by a hinge and analyzed in the same manner. For both vehicle types, impact force estimates derived via the inertial estimation method trended strongly with the impact forces measured by the instrumented wall used in the study.

A procedure for estimating impact forces using vehicle deceleration data is outlined by Eller and Reid (2007). In this method, the lateral and longitudinal coordinate system is transformed to coincide with that of the barrier using yaw measurements, and lateral impact forces are calculated accordingly using vehicle deceleration measurements.

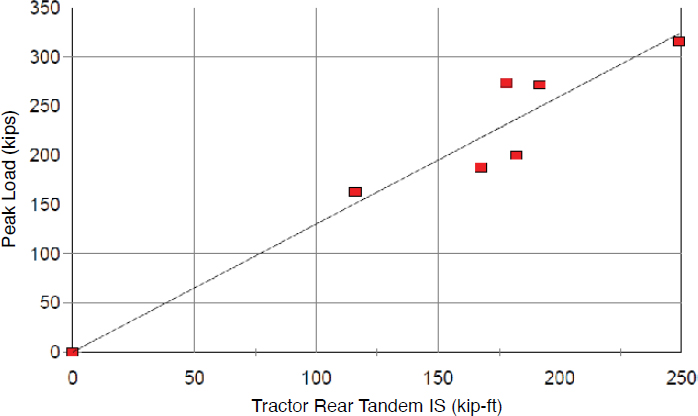

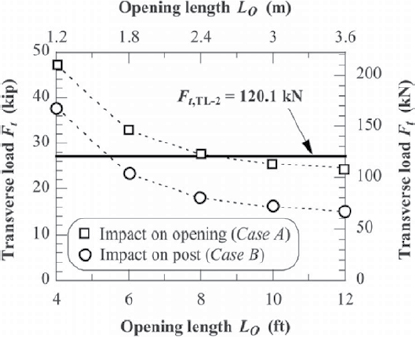

Linear Regression from Impact Severity

In a research effort to design a TL-5 F-shape barrier, researchers at MwRSF developed an alternative method of estimating vehicle impact forces (Faller et al. 2004). The alternative method correlates impact forces measured from vehicle inertia with measured impact severities using linear regression. To develop the relationship, estimated peak lateral loads were plotted against impact severity for six tractor-tank trailer crash tests performed at TTI. Plots of peak lateral loads versus total impact severity and rear tandem impact severity are shown in Figures 8 and 9, respectively.

The results of this study suggested that the relationship between impact severity and peak lateral impact load was roughly linear. The approximate linear increase of peak lateral impact load with respect to the total tractor-trailer impact severity was

| (12) |

where Ft was the peak lateral impact load (kips) and IStotal was the total impact severity of the tractor-tank trailer (kip-ft). Similarly, the approximate linear increase of peak lateral impact load with respect to the rear tandem impact severity was

| (13) |

where ISrear tandem was the impact severity of the rear tandem (kip-ft). Using the nominal MASH 2016 TL-5-12 impact severity of 443.9 kip-ft, the peak lateral force estimated using Equation 12 is 246 kips. To estimate the impact force using Equation 13, the research team first estimated the average weight carried by the rear tandem axle in a comparison of known measurements from crash-tested tractor-tank trailers. It was determined that the average rear tandem axle weight for the MASH tractor-tank trailer was 34,145 lb. Using this axle weight, the peak lateral force estimated using Equation 13 is 248 kips. In sum, this study estimates the nominal MASH TL-5 impact load at just under 250 kips.

AASHTO LRFD BDS Design Parameters

Design parameters currently recommended in AASHTO LRFD BDS have not been updated to reflect the more severe impact conditions of MASH. Additionally, advances in technology have allowed for a more confident estimation of these parameters. As such, several alternative design values have been proposed in the years following the implementation of MASH.

Existing AASHTO LRFD BDS Design Parameters

Current AASHTO LRFD BDS design loads for bridge rails are shown in Table 4. The current design loads were derived from the results of instrumented wall tests performed at TTI in the 1980s (Noel et al. 1981; Beason et al. 1989). Where necessary, dimensional analyses were performed to correct the instrumented wall measurements for changes in impact conditions and barrier height (Bligh et al. 2017). Minimum rail heights required for vehicle stability were determined via crash testing.

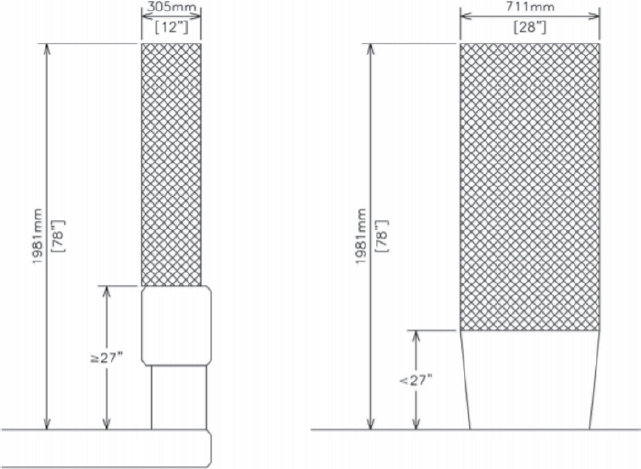

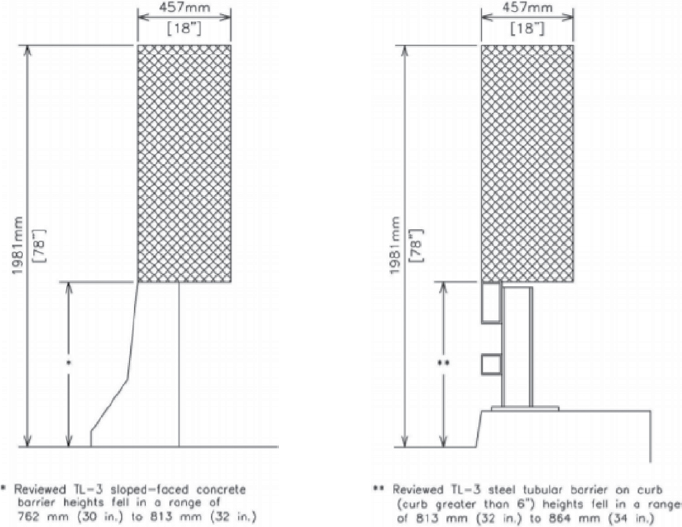

Contemporary Minimum Height Requirements

When a vehicle strikes a bridge rail system, an overturning moment proportional to the height discrepancy between the vehicle’s center of mass and the resultant force of the rail is produced. For the vehicle to remain stable, the height of the barrier must be sufficiently tall such that the

Table 4. Current AASHTO LRFD BDS design parameters for bridge rails.

| Design Parameter | Railing Test Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL-1 | TL-2 | TL-3 | TL-4 | TL-5 | TL-6 | |

| Minimum Height of Rail, H (in.) | 27.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 32.0 | 42.0 | 90.0 |

| Lateral Force, Ft (kips) | 13.5 | 27.0 | 54.0 | 54.0 | 124.0 | 175.0 |

| Longitudinal Force, FL (kips) | 4.5 | 9.0 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 41.0 | 58.0 |

| Vertical Force, Fv (kips) | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 18.0 | 80.0 | 80.0 |

| Distribution of Lateral Force, Lt (ft) | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 8.0 | 8.0 |

| Distribution of Vertical Force, Lv (ft) | 18.0 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 |

| Height of Resultant Load, He (in.) | 18.0 | 20.0 | 24.0 | 32.0 | 42.0 | 56.0 |

weight of the vehicle can negate the overturning moment. The implementation of MASH was accompanied by near-universal increases to impact severities. Increases to vehicle speeds and weights result in more significant overturning moments exerted during impact, diminishing the validity of current height requirements. As such, in the years following the implementation of MASH, several studies have been performed to determine new height requirements. Additionally, full-scale crash tests performed under MASH test conditions can be used to verify existing or alternative height requirements.

TL-1 Minimum Height

Researchers at the MwRSF conducted a full-scale crash test on a timber bridge rail to MASH test designation no. 1-11 in 2009 (Rosenbaugh et al. 2009). The bridge rail was 19.75-in. tall, significantly shorter than the current TL-1 height requirement of 27 in., but it successfully redirected the 2270P pickup. The results of this test, shown in Figure 10, indicate that the current height requirement of 27 in. is sufficient for TL-1 systems.

TL-2 Minimum Height

In 2018, MwRSF conducted a full-scale crash test on a combination bridge rail to MASH test designation no. 2-11 (Bielenberg et al. 2020). The combination rail was 48-in. tall, with a 24-in. steel structure mounted on a 24-in. rigid concrete parapet. In the test, the 2270P vehicle maintained stability while contacting the upper rail only minimally, as shown in Figure 11. The 24-in. concrete parapet, then, was believed to be the primary contributor to the stability of the vehicle, suggesting that the current 27-in.-height requirement is sufficient for TL-2 systems.

In 2022, TTI conducted a full-scale MASH TL-2 crash test on a 20-in.-tall permanent low-profile barrier. This 20-in.-tall barrier met the performance criteria in MASH.

TL-3 Minimum Height

In 2017, research was conducted at TTI under NCHRP Project 20-07(395) to determine the MASH equivalency of NCHRP Report 350-approved bridge rail systems (Silvestri-Dobrovolny et al. 2017). After an analysis of full-scale crash tests failed to produce a confident TL-3 height requirement for MASH conditions, computer simulations were performed in LS-DYNA to estimate the minimum barrier height for vehicle stability. Simulations were conducted with a

vertical, rigid barrier at heights of 27 in., 28 in., and 29 in. impacted by the 2270P pickup. The critical roll scenario from each simulation is shown in Figure 12. The simulated crash test of the 27-in. barrier resulted in vehicle rollover. At a barrier height of 28 in., the vehicle did not experience rollover but was on the edge of instability. Confident stability was observed at a barrier height of 29 in.; the vehicle experienced some roll motion after impact but was stable throughout the test. The resulting minimum height recommendation for TL-3 systems, then, was 29 in.

Two full-scale crash tests were performed to MASH test designation 3-11 by MwRSF in 2018 on a 30-in.-tall timber rail (Schmidt et al. 2019). Both tests were successful, with the 2270P pickup experiencing minimal roll. The rail was backed by a tall, timber noise wall, but the test vehicle did not engage the noise wall; therefore, the 30-in. rail was deemed sufficient for maintaining stability. The maximum roll experienced by the vehicle in the two tests is shown in Figure 13.

TL-4 Minimum Height

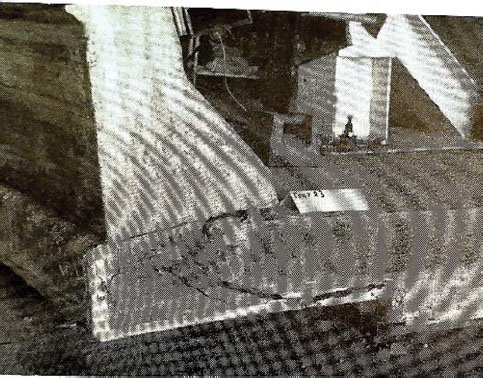

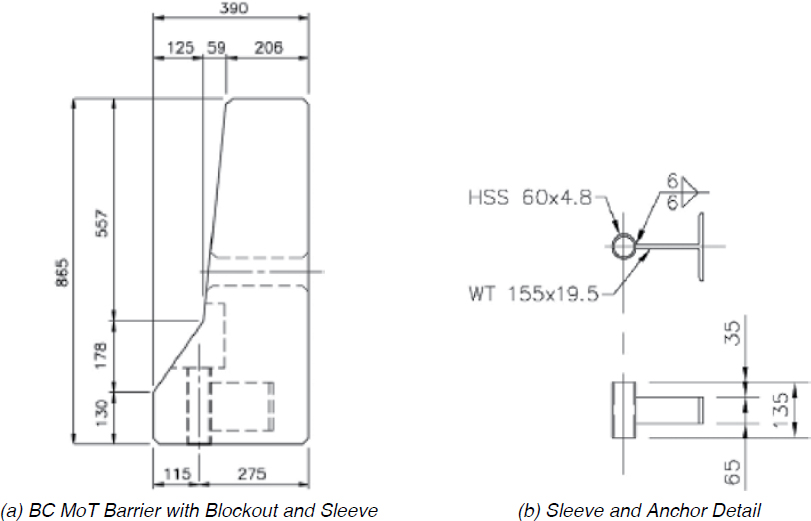

In 2006, as part of an effort to assess the effects of the proposed changes to impact conditions under MASH, MwRSF conducted a full-scale crash test according to MASH test designation no. 4-12 on a 32-in.-tall New Jersey safety shape barrier (Polivka et al. 2006). While the 32-in. test article was proven adequate for TL-4 conditions under NCHRP Report 350, it failed to successfully redirect the impacting vehicle. The SUT rolled over the barrier, as shown in Figure 14.

Under a similar study, TTI performed a full-scale crash test according to MASH test designation 4-12 on a 32-in. New Jersey safety shape bridge rail (Bullard et al. 2010). In this test, conducted in 2010, the SUT maintained stability, but researchers determined the vehicle would have rolled over the barrier had the test installation length been longer. The critical roll angle experienced by the test vehicle is shown in Figure 15. The results of the test, then, agreed with those of a similar test performed by MwRSF in 2006 (Polivka et al. 2006). The required height for stability in TL-4 impacts is greater than 32 in.

With the 32-in. height deemed insufficient, multiple studies were performed to establish an alternative minimum height for TL-4 barriers. In 2011, researchers at TTI conducted a parametric simulation study using LS-DYNA to investigate the effect of barrier height on vehicle stability (Sheikh et al. 2011). Rigid, single-slope barriers of varying heights were impacted in a series of simulated tests conforming to MASH test designation 4-12. Beginning with a barrier

height of 42 in., the height was incrementally reduced until a critical roll scenario was achieved at a barrier height of 36 in., as shown in Figure 16. As a result of the study, a minimum height requirement of 36 in. was proposed.

To investigate the proposed height requirement, a full-scale crash test conforming to MASH test designation no. 4-12 was performed on a 36-in. single-slope barrier. The results of the test were consistent with the simulation study; the SUT maintained stability throughout the test, as shown in Figure 17. In summary, this study established a crash-tested minimum TL-4 barrier height of 36 in. required to maintain SUT stability.

In 2012, an LS-DYNA computer simulation study was performed at MwRSF to determine the critical height for TL-4 barriers (Rosenbaugh et al. 2012). By varying the height of a vertical, rigid barrier and accounting for a critical vehicle damage mode, the required barrier height was determined to be 34.5 in. The successful simulations with maintained SUT stability are shown in Figure 18. This barrier height has not been confirmed in full-scale crash testing.

Multiple 36-in. barriers have been successfully crash tested to MASH TL-4 criteria since the proposal of the alternative minimum barrier height. MwRSF conducted a successful MASH test designation no. 4-12 crash test on a 36-in.-tall single-slope concrete barrier (Rosenbaugh 2019). In the same year, TTI performed a successful MASH 4-12 crash test on a 36-in.-vertical concrete

barrier (Bligh et al. 2018). Successful MASH TL-4 tests on 36-in. concrete barriers are shown in Figure 19.

Additionally, the 36-in. minimum height has been evaluated for metal post-and-beam systems. In 2019, MwRSF conducted full-scale crash tests according to MASH test designation nos. 4-10, 4-11, and 4-12 on a 36-in. steel tube bridge rail (Pena et al. 2019). All tests were successful, further substantiating the sufficiency of 36-in.-tall barriers to contain and redirect vehicles under TL-4 impact conditions. The results of MASH test no. 4-12 performed in the MwRSF study are shown in Figure 20.

TL-5 Minimum Height

Neither vehicle dimensions nor impact conditions were changed in the conversion from NCHRP Report 350 to MASH. As such, it is believed by researchers at MwRSF that the existing TL-5 minimum barrier height of 42 in. remains sufficient for MASH conditions (Stolle et al. 2022). In a MASH-equivalency study, researchers at TTI evaluated TL-5 barriers using this height requirement (Silvestri-Dobrovolny et al. 2017). Additionally, several successful MASH TL-5 crash tests have been performed on barriers with heights less than or equal to 42 in. These tests, which are summarized in Table 5, suggest that the existing height requirement is adequate for MASH TL-5 conditions.

Table 5. Summary of successful crash tests with 42-in. height to MASH test designation no. 5-12.

| Testing Organization | Year | Barrier Type | Barrier Height (in.) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MwRSF (Faller et al. 2004) | 2005 | Open concrete bridge rail | 42.0 | Success |

| MwRSF (Rosenbaugh et al. 2007) | 2007 | Vertical concrete median barrier | 42.0 | Success |

| TTI (Buth and Menges 2011) | 2011 | Concrete safety shape bridge rail | 41.3 | Success |

| TTI (Sheikh et al. 2016) | 2016 | Metal post-and-beam | 42.0 | Success |

| TTI (Williams, Bligh, et al. 2015) | 2018 | Open concrete bridge rail | 42.0 | Success |

TL-6 Minimum Height

Currently, only two full-scale crash tests have been performed to NCHRP Report 350 test designation no. 6-12, both of which featured a 90-in.-tall barrier shown in Figure 21. (Beason et al. 1989; Hirsch and Fairbanks 1984). TL-6 impact conditions did not change in the conversion from NCHRP Report 350 to MASH, and no full-scale tests have been conducted since the adoption of MASH criteria.

In 2018, an LS-DYNA computer simulation study was performed to estimate the required height for MASH TL-6 barriers (Whitfield 2018). The results of the study suggested that a 62-in. vertical wall could be adequate to prevent a TL-6 tractor-tank trailer from rolling over during impact. The maximum roll of the vehicle in the simulation is shown in Figure 22. The findings of this study have not been confirmed through full-scale crash testing.

Contemporary Design Force Estimates

Contemporary research suggests that the current AASHTO design loads for bridge rails require modification. Uncertainties in the efficacy of current design loads stem from a variety of sources.

Primarily, in the conversion from NCHRP Report 350 to MASH 2016, vehicle characteristics and impact conditions were modified, resulting in greater impact severities, suggesting potential impact force increases. Additionally, current design loads for TL-4 and TL-5 bridge rails were established from crash tests in which the ballast mass was not rigidly secured to the vehicle, potentially resulting in uncharacteristically low impact force estimates (Bligh et al. 2017). As a consequence of the ballast conditions, the impact loads of TL-5 vehicles could require modification despite their weights remaining unchanged in the conversion to MASH. Last, advances in technology have provided insight into impact behavior not available at the formation of the current AASHTO design forces, such as the engagement of trailer boxes and the height at which loads are applied.

TL-3 Design Loads

Using finite element simulations in LS-DYNA, Silvestri-Dobrovolny et al. (2017) estimated TL-3 impact loads as part of a MASH-equivalency study for barriers approved under NCHRP Report 350. A TL-3 impact load estimate of 71 kips exerted at a height of 19 in. was extracted from a simulation in which a MASH 2270P test vehicle impacted a rigid, vertical parapet at 62 mph and at a 25-degree impact angle. The results of this study are listed in Table 9, which summarizes results for TL-3 through TL-6.

Alternatively, if Equation 11 is used to extrapolate instrumented wall loads to the impact conditions of MASH, an estimated TL-3 design load of 52 kips is achieved (Bullard et al. 2010). This extrapolated estimate is also shown in Table 9.

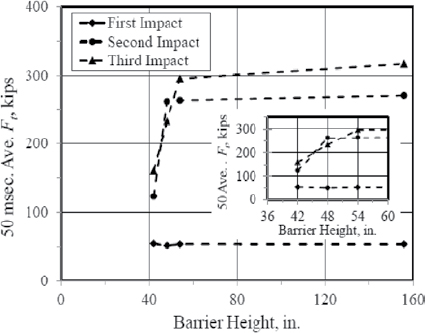

TL-4 and TL-5 Design Loads

Similarly, Bligh et al. (2017) estimated TL-4 and TL-5 impact loads using LS-DYNA simulations. Simulations of SUT and tractor-trailer impacts with rigid barriers of varying heights were performed from which lateral impact loads and their application heights were extracted. Due to the relationship between the barrier height and the interaction between the cargo box and the barrier, impact forces were found to vary significantly with the barrier height. For a relatively short barrier, the floor of the trailer clears the top of the barrier. As a result, the lateral impact

force is significantly reduced, and the vertical force is increased as the vehicle leans on the barrier to remain stable. With increasing barrier height, greater portions of the trailer impact load are exerted laterally onto the barrier, and the vertical force is reduced. The relationship between barrier height and impact behavior is depicted in Figure 23.

The variation of impact loads with respect to barrier height is shown in Tables 6 and 7 for TL-4 and TL-5, respectively. Variations are also demonstrated in Figures 24 and 25. Due to the variation of impact forces with respect to barrier height, Bligh et al. recommended the division of TL-4 and TL-5 into subcategories based on the height of the barrier. Proposed subcategories TL-4-1 and TL-5-1 correspond to the minimum height required for vehicle stability for TL-4 and TL-5, respectively. Subcategories TL-4-2 and TL-5-2 correspond to TL-4 and TL-5 barriers

Table 6. TL-4 impact force variation with barrier heights (Bligh et al. 2017).

| Design Parameter | Barrier Height (in.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | 39 | 42 | Tall | |

| Ft Transverse (kips) | 67.2 | 72.3 | 79.1 | 93.3 |

| FL Longitudinal (kips) | 21.6 | 23.6 | 26.8 | 27.5 |

| Fv Vertical (kips) | 37.8 | 32.7 | 22.0 | — |

| Lt or LL (ft) | 4 | 5 | 5 | 14 |

| He (in.) | 25.1 | 28.7 | 30.2 | 45.5 |

NOTE: Ft = transverse force; FL = longitudinal force; FV = vertical force; Lt = distribution length of transverse force; LL = distribution length of longitudinal force; He = height of transverse and longitudinal loads.

Table 7. TL-5 Impact force variation with barrier height (Bligh et al. 2017).

| Design Parameter | Barrier Height (in.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42 | 48 | 54 | Tall | |

| Ft Transverse (kips) (First Impact) | 54.6 | 51.7 | 53.8 | 53.7 |

| Ft Transverse (kips) (Second Impact) | 123.0 | 261.8 | 263.5 | 270.4 |

| Ft Transverse (kips) (Third Impact) | 159.0 | 232.8 | 295.5 | 316.6 |

| FL Longitudinal (kips) | 73.5 | 74.6 | 77.2 | 72.6 |

| Fv Vertical (kips) | 160.0 | 108.0 | 62.8 | — |

| Lt or LL (ft) | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| He (in.) | 34.3 | 42.9 | 46.6 | 51.7 |

NOTE: — = not applicable.

taller than the minimum required height for vehicle stability, respectively. The final design parameters proposed in this study are collected in Table 9. The estimates produced in these rigid wall simulation studies are considered to be conservative, as they correspond to simulated impacts with rigid parapets. In reality, any impacted barrier will deform, if only slightly, decreasing the sustained impact force.

Most recently, Cao et al. (2019) performed high-fidelity finite element simulations in LS-DYNA to investigate the impact behavior of solid parapet barriers. Simulations were conducted with a single-slope TL-4 barrier and a safety-shaped TL-5 barrier impacted by an SUT model revised to represent MASH conditions and a 36000V tractor-trailer model, respectively. These impact simulations are depicted in Figure 26.

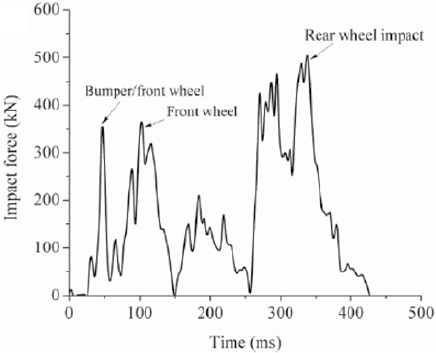

The progression of the simulated TL-4 test is shown in Figure 27. The corresponding filtered impact force response is shown in Figure 28. The maximum lateral force measured in the simulation was roughly 112 kips, significantly higher than the impact forces measured in the rigid wall tests performed by Bligh et al. in 2017.

Likewise, the progression of the simulated TL-5 test is shown in Figure 29. The corresponding, filtered impact force response is shown in Figure 30. The maximum lateral force measured in the simulation was roughly 415 kips. Similar to the simulated TL-4 test, this maximum force was remarkably higher than the impact forces measured by Bligh et al. in 2017.

Cao et al. also investigated the height at which lateral forces were exerted in the simulated impacts. Impact heights varied significantly between the three characteristic phases of impact and between the TL-4 and TL-5 vehicles. Most notably, the third, and most severe, impact phase for the TL-4 SUT was found to exert forces significantly lower than the height of the barrier. Conversely, the third impact phase for the TL-5 tractor trailer was found to exert forces across the entire height of the barrier. Detailed impact height distributions are shown in Table 8.

TL-4 impact loads were also estimated using instrumented wall extrapolation per Equation 11 (Bullard et al. 2010). These estimates are shown alongside LS-DYNA estimates in Table 9.

TL-6 Design Loads

Full-scale crash testing of TL-6 systems is rare. As of 2019, only two full-scale crash tests of tractor-tanker vehicles have been performed, neither of which were under MASH criteria. In the instrumented wall test from which the current AASHTO LRFD BDS design loads were extracted, a 90-in.-vertical barrier was impacted by an 80,000-lb tractor tanker (Beason et al. 1989). In this test, a peak dynamic tail-slap load of 408 kips acting at a height of 56 in. was measured by the instrumented wall. On-board accelerometers corroborated this data. The product of the peak tail-slap acceleration and the participating trailer mass was roughly 400 kips. Additionally, in another test, a 90-in. “Roman wall” concrete barrier successfully redirected a tractor tanker (Hirsch and Fairbanks 1984). The barrier impacted in this test was designed assuming two applied loads: a 60-kip load applied at 21 in. corresponding to the weight of the trailer and a 144-kip load applied at 84 in. corresponding to the ballast weight. Both forces were derived from extensive assumptions of the vehicle’s mass distribution and impact behavior.

As part of a research effort to design a cost-effective TL-6 barrier, researchers at the MwRSF elected to use a 350-kip design load for a rigid barrier impact (Whitfield 2018). In the study, the lower-bound strength of the successfully tested Roman wall barrier was estimated via traditional yield-line analysis to be 350 kips. In the full-scale crash test of that barrier, minimal damage was

Table 8. Impact force height distribution (Cao et al. 2019).

| Vehicle | Barrier Height (in.) | Height Range for Impact Force Application (in.) (Percentage of Total Barrier Height) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Impact | Second Impact | Third Impact | ||

| SUT | 36 | 18–23 (50–64%) | 20–26 (56–72%) | 5–17 (14–47%) |

| Tractor Trailer | 42 | 20–25 (48-60%) | 2–14 (5–33%) | 2-42 (5–100%) |

Table 9. Alternative AASHTO LRFD BDS design values for TL-3 through TL-6.

| Design Parameter | Railing Test Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL-3a | TL-4-1b | TL-4-2 | TL-5-1 | TL-5-2 | TL-6 | |

| Bridge Rail Height, H (in.) | ≥ 29 | 36 | > 36 | 42 | > 42 | —c |

| Lateral Force, Ft (kips) | 71 52d |

70 76d 112f |

80 76d 112f |

160 415f |

260 415f |

350e 408g |

| Longitudinal Force, FL (kips) | — | 22 | 27 | 75 | 75 | — |

| Vertical Force, Fv (kips) | — | 38 | 33 | 160 | 108 | — |

| Distribution of Lateral Force, LL (ft) | — | 4 | 5 | 10 | 10 | — |

| Distribution of Vertical Force, Lv (ft) | — | 18 | 18 | 40 | 40 | — |

| Height of Resultant Load, He (in.) | 19 | 25 | 30 | 34 | 43h | — |

aTL-3 parameters extracted from NCHRP Project 20-07(395) (Silvestri-Dobrovolny et al. 2017) unless noted.

bTL-4 parameters extracted from NCHRP Web-Only Document 326 (Bligh et al. 2017) unless noted.

cDashes indicate parameters without alternative proposed values.

dSecondary TL-3 and TL-4 design loads extracted from NCHRP Web-Only Document 157 (Bullard et al. 2010).

eTL-6 design load extracted from TL-6 barrier design study (Whitfield 2018).

fExtracted from finite element simulations (Cao et al. 2019).

gPeak dynamic load extracted from instrumented wall study with TL-6 test vehicle (Beason et al. 1989).

hIf barrier height exceeds 54 in., use He = 52 in.

observed. As such, the researchers hypothesized that the lateral load exerted by the tractor tanker was no greater than 350 kips.

In the same study, a series of simulations was performed in LS-DYNA in which a tractor-tank trailer impacted a rigid wall of varying heights at 50 mph and at an impact angle of 15 degrees. In agreement with the findings of similar TL-4 and TL-5 simulations, lateral impact forces were found to increase with increasing barrier height. Maximum impact forces of 136, 159, 168, and 160 kips were imparted to barriers with heights of 50, 62, 70, and 90 in., respectively. However, these impact forces were not used as design forces in the study, as the goal of the simulation effort was to determine the minimum TL-6 barrier height, rather than the design load.

Alternative Design Parameters

Design parameter alternatives extracted from contemporary research are presented in Table 9. Studies in which parameters were proposed are denoted with superscripts. Parameters with no recommended modifications are indicated by dashes.

Design and Analysis of Bridge Rail Systems

Bridge rail systems protect drivers from the dangerous conditions of elevated roadways. To ensure the safety of passengers in an errant vehicle, a bridge rail must have a structural capacity sufficient to resist the forces exerted by the vehicle during the impact sequence and contain the vehicle. As such, structural adequacy is a crucial design consideration for any bridge rail. Structural failure of a bridge rail system is likely to result in a fatal accident.

Bridge rail systems are highly diverse. A variety of materials, shapes, and features make up the current portfolio of in-use systems. In general, bridge rail systems can be categorized as concrete,

metal post-and-beam, combination, flexible, or timber. Additional specializations can be added to any system, such as curbs, pedestrian railings, or retaining walls. In this section, the existing philosophy of AASHTO LRFD BDS Section 13 is presented alongside summaries of relevant, contemporary research for the entire landscape of bridge rail systems.

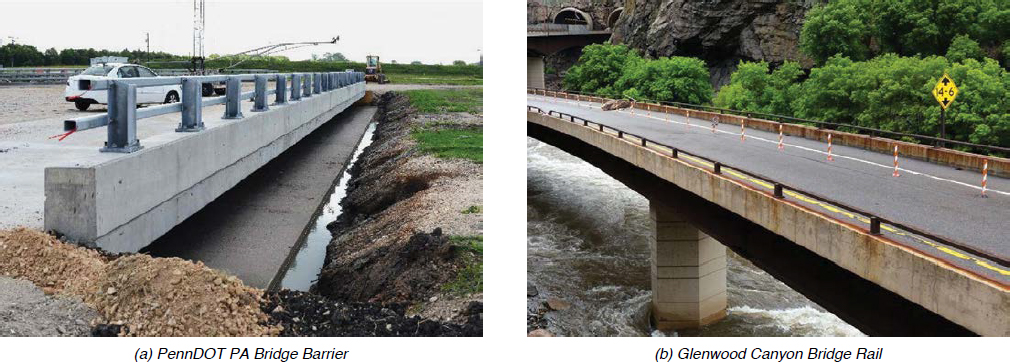

Concrete Bridge Rails

Concrete barriers are the most common type of safety hardware found on bridges and can be categorized as either solid concrete parapets or open concrete rails, as shown in Figure 31. Design philosophies and analysis procedures differ between these bridge rail systems.

Solid concrete parapets are continuous slabs of reinforced concrete often featuring a specialized face shape to influence impact behavior. Typical solid concrete parapets include the New Jersey safety shape, the F-shape, the single-slope, and the vertical wall. Alternatively, open concrete rails are post-and-beam systems composed of a continuous concrete beam secured to concrete posts extending from the deck. Due to their frequency of use, extensive research has been conducted on concrete bridge rails since the formulation of the current AASHTO design philosophy.

Existing AASHTO LRFD BDS Philosophy

Solid concrete parapets and open concrete rails require different design and analysis methods. As such, AASHTO provides separate guidance for each type of concrete barrier.

Solid Concrete Parapets

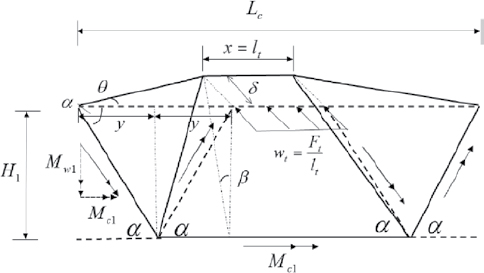

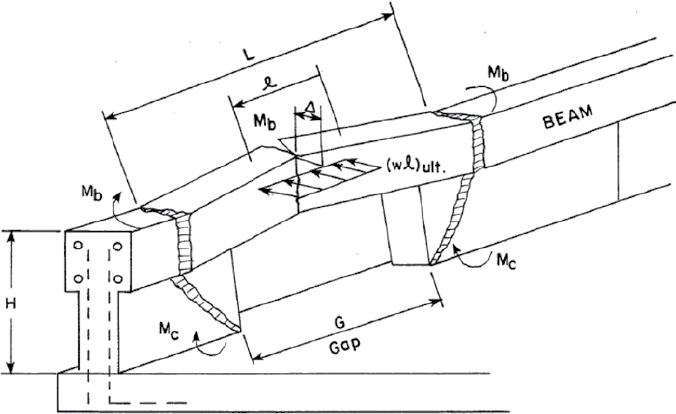

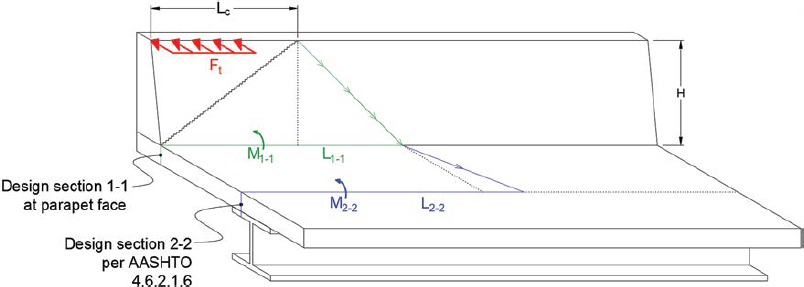

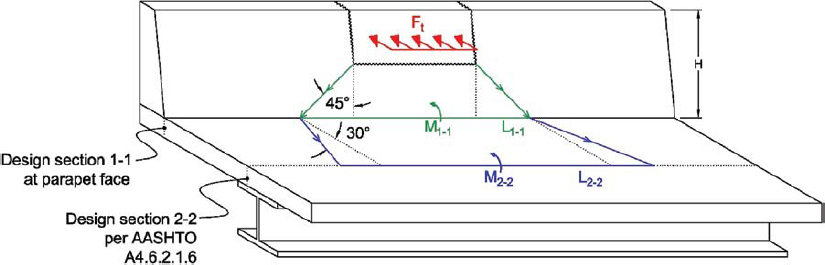

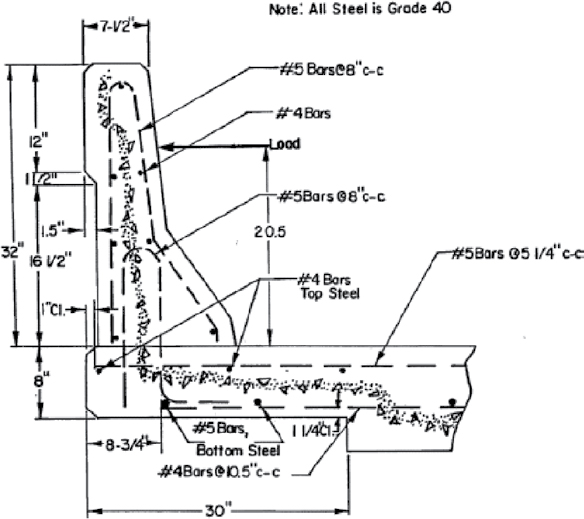

The current AASHTO design procedure for solid concrete parapets employs a yield-line analysis method proposed by Hirsch (1978). The method is founded in an assumed v-notch failure mechanism about the impact location, as shown in Figure 32. Rigid, triangular plates rotate about lines of yielded steel to produce the failure pattern. To determine the capacity of the barrier, an energy balance is performed with a virtual displacement, Δ, applied at the top of

the parapet. External work due to the applied force, Ft, is equated to the internal work done by the rotation of the rigid plates about the yield lines:

| (14) |

where Mi is the flexural strength of the parapet about a particular yield line, and θi is the corresponding rotation about that yield line.

Manipulating this relationship to reflect the flexural strength of the parapet about its longitudinal and vertical axes produces the current AASHTO design equation for a continuous, solid concrete parapet:

| (15) |

in which the result, Rw, is the critical load applied at the top of the parapet at which the parapet will experience the yield-line failure mechanism; Lt is the longitudinal distribution length of the impact force (ft); Mw is the flexural resistance of the parapet about its vertical axis (k-ft); Mb is the additional flexural resistance of a beam component (k-ft), if any; Mc is the flexural resistance of the parapet about its longitudinal axis (k-ft/ft); H is the height of the parapet (ft); and Lc is the critical length of the yield-line pattern (ft). The critical length is determined as the length of the yield-line pattern, which minimizes the resistance of the barrier:

| (16) |

The result of Equation 15, Rw, is depicted in Figure 32.

An additional yield-line mechanism is possible at locations of parapet discontinuities, such as parapet terminals or untreated expansion joints. In this alternative failure mechanism, one rigid plate rotates about one yield-line extending outward from the parapet base at the free edge, as shown in Figure 33. By applying an energy balance to the alternative yield-line mechanism, the current AASHTO design equations for solid concrete parapet free ends are produced.

| (17) |

| (18) |

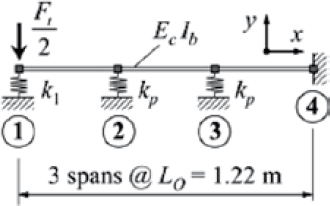

Open Concrete Rails

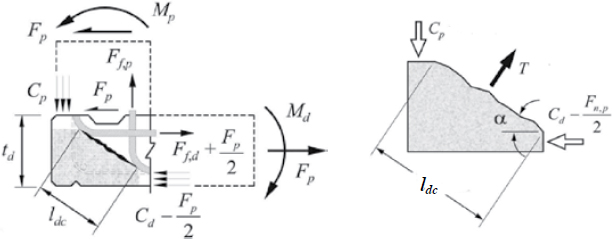

Open concrete rails may be favored over solid barriers for aesthetic considerations or in scenarios where vented water flow is required in the event of an overtopping flood. Currently, AASHTO recommends open concrete rails be designed in a different manner than the yield-line method used for solid parapets. In the yield-line method for solid parapets, the flexural strength of the concrete is used to determine the critical length of the failure mechanism. Alternatively, for concrete post-and-beam systems, the flexural strengths of the posts about the longitudinal axis and of the beam about the vertical axis are used to determine the critical number of railing spans participating in failure and, consequently, the lateral resistance of the barrier. For reference, single-, two-, and three-span failure modes are shown in Figure 34. It should be noted that the illustration in Figure 34 is specific to metal post-and-beam systems. Mp in Figure 34 is analogous to the flexural resistance of the concrete beam about the vertical axis, Mb.

For interior failure modes involving an odd number of railing spans, N, Equation 19 applies.

| (19) |

Whereas for interior failure modes involving an even number of railing spans, Equation 20 applies

| (20) |

in which L is the post spacing (ft), Mb is the flexural resistance of the beam about the vertical axis (k-ft), and Pp is the shear force on a single post (kips), which is equal to

| (21) |

where Mc,post is the flexural resistance of a single post about the longitudinal axis (k-ft) and is the height of the barrier resultant force (ft). Due to the rigidity of concrete barrier systems, the height of the resultant barrier force is considered to be equal to the height of the barrier.

To determine the resistance of an interior span, Equations 19 and 20 are evaluated for increasing values of N until the minimum value of R is identified. For end segments, the resistance of the barrier is calculated in Equation 22.

| (22) |

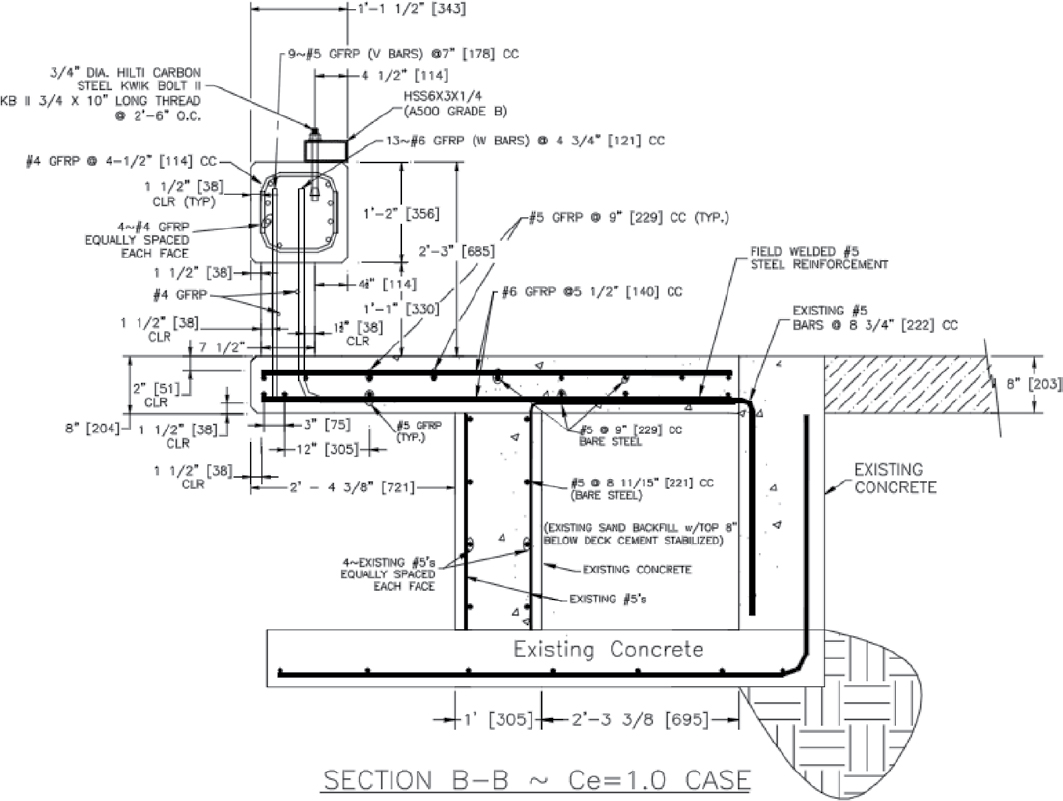

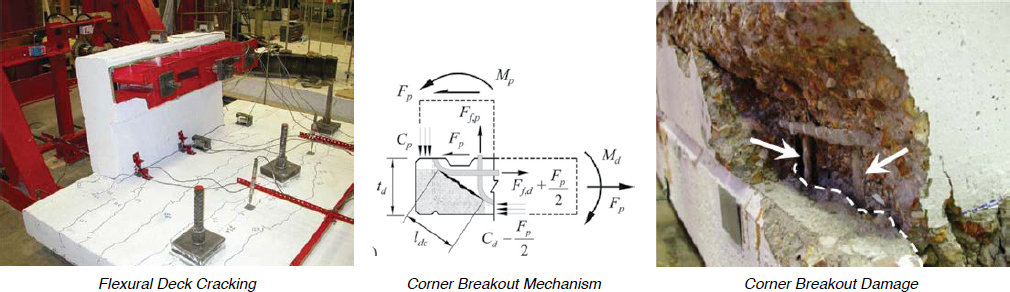

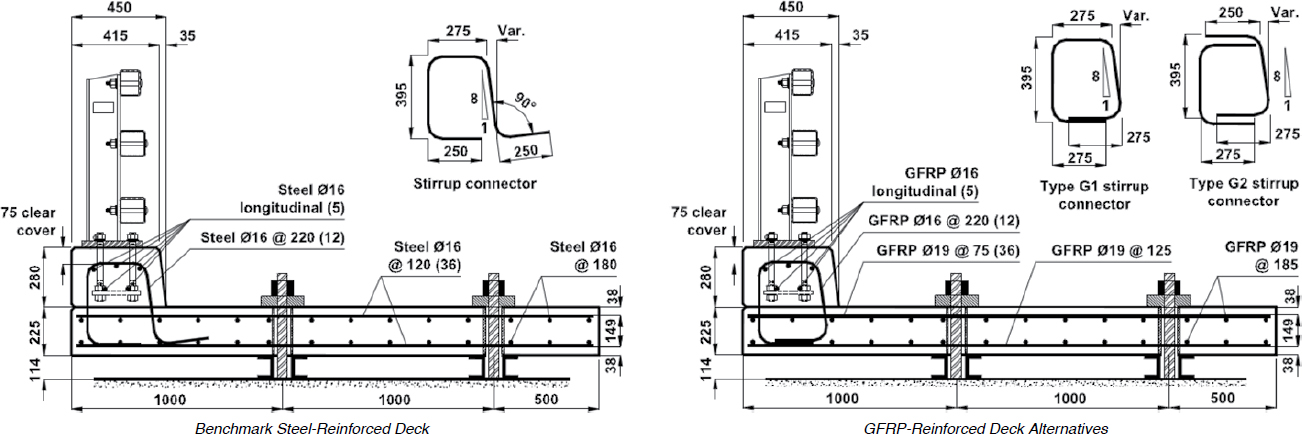

GFRP-Reinforced Concrete Rails

Glass fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRP) reinforcement is becoming increasingly common in practice, but GFRP-reinforced parapets are not yet currently addressed in AASHTO LRFD BDS Section 13 guidance. AASHTO issued the first LRFD Bridge Design Guide Specification for

GFRP-Reinforced Concrete Bridge Decks and Traffic Railings in 2009 (AASHTO 2009a), followed by a 2nd edition, LRFD Bridge Design Guide Specification for GFRP-Reinforced Concrete with “Bridge Decks and Traffic Railings” removed from the title (AASHTO 2018). In 2020, a revised 2nd edition was published with errata (AASHTO 2020b). Due to the brittle nature of GFRP compared to steel, yield-line approaches cannot be applied in the design of GFRP-reinforced bridge rails. The 2nd edition Guide Specification notes that inelastic methods are permitted for GFRP-reinforced concrete railings, but “equilibrium of forces and compatibility of deformations shall be explicitly accounted for by implementing suitable analytical or numerical methods.” A post-and-beam design methodology is provided in Appendix A5 of the 2nd edition Guide Specification, which appears similar to the method found in Appendix A13 of the AASHTO LRFD BDS and is similarly termed an “inelastic” method. However, the provision requiring that compatibility is enforced together with equilibrium requires an additional layer of rigor compared to metal post-and-beam inelastic analyses, which is necessary to ensure adequate safety when large strains are anticipated in GFRP. Resistance factors for flexure with sections controlled by high GFRP strains are dependent on the GFRP strain and can fall as low as 0.55 according to the 2nd edition Guide Specification.

State of the Art

Due to the frequency with which concrete rails are implemented on bridges, many research efforts have been conducted regarding their analysis and design. These efforts have been focused primarily on solid concrete parapets, though guidance does exist for open concrete rails that is not currently found in AASHTO LRFD BDS.

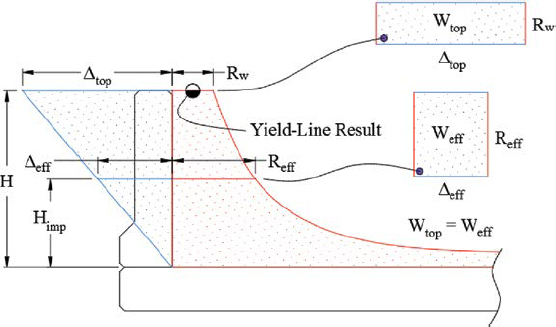

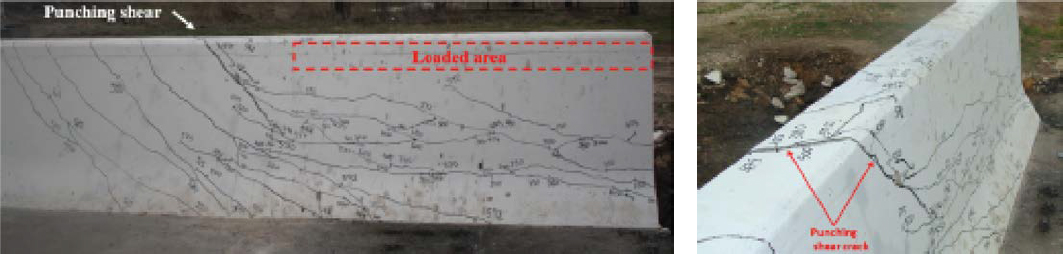

Steel-Reinforced Solid Concrete Parapets

Since the formulation of the current AASHTO LRFD BDS guidance on solid concrete parapet design, advances in computer simulation and a large number of crash tests have brought the accuracy of the current methodology into question. The current, v-shaped yield-line mechanism, for example, is rarely observed in full-scale crash tests involving solid concrete parapets. Based on impact force estimates, damage to solid concrete parapets designed according to current guidance is generally less severe than would be expected, indicating significant reserve capacity not accounted for in the current methodology. Recent research has posed three possible explanations for the current misrepresentation of parapet strength: (1) the actual yield-line pattern differs from the pattern presented in AASHTO LRFD BDS, (2) deformation and inertial activation of the barrier results in higher capacity, and (3) the lateral load should be applied at a height more representative of actual impacts, rather than at the top of the barrier. These explanations are discussed herein. Additionally, current AASHTO LRFD BDS guidance suggests that the failure of a parapet barrier will be governed by flexure. Conversely, recent research indicates that, in some cases, punching shear strength may govern the strength of the barrier.

Modified Yield-Line Pattern

A series of experimental studies on the failure mechanisms of parapet barriers performed in 2004 was the first to explicitly suggest an alternative yield-line mechanism (Korea Highway Corporation 2004; Woo et al. 2004; Kang et al. 2004). With these studies as a foundation, Jeon et al. (2008) conducted static loading tests on the standard Korean barrier shape to investigate failure behavior, as shown in Figure 35.

In Jeon et al. (2008), two full-scale parapet specimens were loaded with a ramping force until failure. The cracking patterns of each specimen at failure are shown in Figure 36. Values corresponding to each crack indicate the applied load (kN) at which the crack formed. In both tests, cracks formed predominately in a trapezoidal shape about the load application area, terminating at the top of the toe rather than at the base of the barrier. With the cracking patterns clearly

deviating from the yield-line mechanism currently presented in AASHTO LRFD BDS, the research team proposed a suite of possible yield-line patterns (Figure 37).

Possible yield-line mechanisms varied significantly. The current AASHTO LRFD BDS yield-line pattern is depicted in pattern YL1. Additional mechanisms following the same pattern as YL1 are shown, YL2 and YL3, which terminate at the top and bottom of the toe, respectively. The novel yield-line mechanism proposed by the research team, YL4, is characterized by a trapezoidal shape whose bottom edge is coincident with the top of the toe. YL5 describes a single, horizontal yield line at the top of the toe.

The parapet strength at each potential failure mechanism was evaluated. The strength of yield-line mechanisms YL1, YL2, and YL3 were determined from current AASHTO LRFD BDS guidance. Pattern YL5 was omitted from the evaluation, as its occurrence was deemed impossible for sufficiently long barrier spans.

Trapezoidal pattern YL4, which was of particular interest following the results of the static load tests, was analyzed in detail. The mechanism is shown in Figure 38. Using the same principles as those used to form the current AASHTO LRFD BDS guidance, Jeon et al. (2008) derived alternative strength equations corresponding to the trapezoidal yield-line mechanism. Equating the external work done by the applied load and the internal work associated with the rotation of the yield lines yielded a relationship between the applied load and the deformation of the barrier:

| (23) |

where H1 is the height of the trapezoid, Mw1 is the flexural strength of the parapet about the vertical axis over height H1, Mc1 is the flexural strength of the parapet about the longitudinal axis over height H1, x is the length of the base of the trapezoid, and α is the angle at which the diagonal yield-lines extend from the base of the trapezoid. Minimizing Equation 23 resulted in

| (24) |

The estimation of the parapet strength in Equation 24 assumes that the base of the trapezoid has a length x equal to the load application width, Lt. Values of x less than Lt are possible but were neglected in this study.

The strength of the barrier in each test was determined using yield-line patterns YL1 through YL4 and compared to the failure strength. This comparison is shown in Table 10. The trapezoidal

Table 10. Comparison of ultimate strengths (Jeon et al. 2008).

| Test | Lt (mm) | Theoretical Flexural Strength (kN) | Test Load at Failure (kN) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YL1 | YL2 | YL3 | YL4 | |||

| 1 | 1,070 | 614.0 | 442.6 | 513.6 | 434.3 | 330.0 |

| 2 | 2,440 | 751.7 | 566.2 | 659.4 | 528.4 | 360.0 |

yield-line pattern resulted in the lowest theoretical barrier strength. The research team suggests that because the trapezoidal yield-line pattern yielded the strength nearest the actual failure strength, this alternative yield-line pattern is the most accurate. However, the analysis assumed a trapezoid base length of Lt, which does not agree with the horizontal yield-line length observed in the static load tests. Additionally, it is possible that the ultimate strength of the barrier was controlled by punching shear rather than by flexure, further obfuscating the direct comparison between the theoretical yield-line strength and the measured failure load.

The trapezoidal modified yield-line mechanism was further studied by Khederzadeh and Sennah (2014). In this effort, the length of the horizontal yield-line at the base of the trapezoidal failure pattern was allowed to vary as a function of Lt, resulting in a more robust analysis method. Three unique scenarios were evaluated: (1) the length of the horizontal yield-line, x, is greater than the load application length, (2) the length of the horizontal yield-line, x, is equal to the load application length, and (3) the length of the horizontal yield-line, x, is less than the load application length. In addition to the introduction of variable base length, this method deviated from that of Jeon et al. (2008) in that the cantilever strength of the parapet was separated into the strength at the parapet base, Mc,b, and the average strength over the height of the parapet, Mc,w. For each scenario, equations were derived to estimate parapet strength. Khederzadeh and Sennah (2014) further bolstered the trapezoidal yield-line analysis method by expanding its application to parapet-end conditions, such as terminals and expansion joints. The suggested failure shape at barrier ends was clearly observed in a quasi-static load test performed by Alberson et al. (2005), the results of which are shown in Figure 39. The tested barrier was an F-shape bridge rail.

Each case is described by the product of the load application length, Lt, and a coefficient modifier, n, which varies from 0 to 2. These cases and their corresponding critical lengths and

Table 11. Modified yield-line analysis case directory.

| Case | Condition | Demonstration | Critical Length | Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| x ≥ Lt 1 ≤ n1 ≤ 2 |

Interior | Figure 40 | Equation 25 | Equation 26 |

| End | Figure 41 | Equation 27 | Equation 28 | |

| x < Lt 0 ≤ n2 < 1 |

Interior | Figure 42 | Equation 29 | Equation 30 |

| End | Figure 43 | Equation 31 | Equation 32 |

resistances are expressed in the figures and tables that follow. Figures and equations are linked to their respective cases in Table 11.

| (25) |

| (26) |

| (27) |

| (28) |

| (29) |

| (30) |

| (31) |

| (32) |

Using these equations, Fadaee et al. performed parametric studies on TL-4 and TL-5 parapet strengths with varying rebar spacing (Fadaee et al. 2018; Fadaee and Sennah 2018). The critical trapezoid base length and, consequently, the critical lateral load were determined for a variety of reinforcement configurations for a TL-4 F-shape barrier, a TL-4 vertical parapet, and a TL-5 F-shape barrier. With the results of the parametric study, the research team was able to identify the most efficient rebar spacing to achieve the design strength at interior and exterior locations. However, the strengths determined via the modified yield-line method were not compared to strengths determined via the traditional yield-line method.

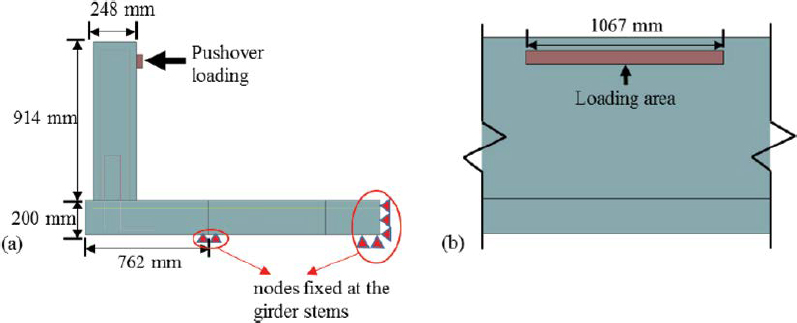

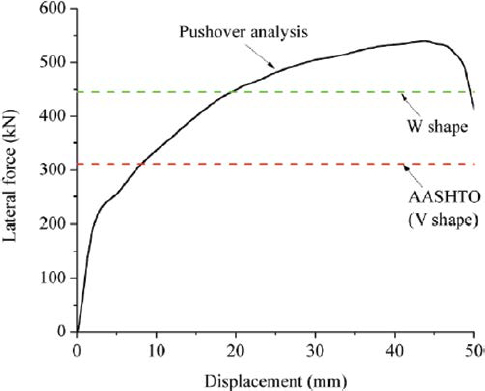

Cao et al. (2019) proposed a similar modified yield-line analysis method as a result of a simulation study of TL-4 and TL-5 concrete bridge rails. Noting a discrepancy between the rigid barrier models used in force estimation studies and the assumption of flexibility in capacity evaluations, Cao et al. performed pushover analyses to investigate the capacity of a TL-4 bridge rail subject to lateral loading. Employing an approach similar to that used in earthquake engineering, a quasi-static force was applied and incrementally increased until failure to obtain a load-deformation curve. The pushover test setup is shown in Figure 44.

The load-deflection curve obtained in the simulated pushover test is shown in Figure 45. The capacity of the simulated barrier was 120 kips. At failure, the maximum reinforcement strain was roughly 1%.

If current AASHTO LRFD BDS guidance was used, the capacity of this barrier would be estimated at just 70 kips—significantly lower than the measured capacity. This discrepancy was attributed to the yield-line mechanism observed in the simulation, which was significantly different from the mechanism assumed in AASHTO LRFD BDS. The yield-line mechanism observed in the pushover simulation is shown in Figure 46.

The yield-line mechanism observed in the test is a clear deviation from the mechanism assumed in AASHTO LRFD BDS. As such, the accuracy with which the traditional yield-line equations

can estimate the barrier capacity is questionable. The modified, trapezoidal yield-line mechanism was also observed in the TL-4 and TL-5 impact simulations carried out in the same study and shown in Figures 47 and 48, respectively. With the trapezoidal yield-line mechanism appearing in the pushover analysis, both simulated crash tests, and a review of other literature, Cao et al. elected to investigate this modified pattern in further detail.

Using a method similar to that with which the traditional yield-line equations were derived (Hirsch 1978), Cao et al. (2019) derived an alternative capacity equation corresponding to the trapezoidal yield-line pattern:

| (33) |

wherein Rw is the critical lateral load, H1 is the height of the barrier, Mw1 is the flexural resistance of the barrier about its vertical axis, and Mc1 is the flexural resistance of the barrier about its longitudinal axis, evaluated on a per-foot basis. A detailed diagram of the yield-line mechanism is shown in Figure 49.

In this study, the modified yield-line method produced a more accurate barrier capacity estimate than the traditional yield-line method. The capacity of the barrier estimated using the modified yield-line method of Equation 33 was 100 kips, which was significantly closer to the measured capacity of 120 kips when compared to the traditional yield-line result of 70 kips. Cao et al. attributed in part the discrepancy between the modified estimate and the measured capacity to other resistance mechanisms associated with complete failure, such as tensile membrane action.

It should be noted that the resistance estimate formed by Cao et al. (2019) is heavily reliant on empirical assumptions. The actual, as-derived equation of the barrier resistance in this study was

| (34) |

in which α is the angle at which the yield lines on the impact face of the barrier extend from the base and x is the length of the top edge of the central trapezoidal plate. To achieve the recommended capacity equation, α was assumed to be 45o and x was assumed to be equal to Lt.

Inertial Activation

An additional modification to the yield-line method was proposed by Schrum et al. (2016). Whereas the previously discussed studies investigated the failure patterns of the yield-line mechanism, Schrum et al. sought a capacity estimation that accounted for the flexibility and inertial activation of the barrier. Traditional yield-line methods use energy conservation principles to determine capacities. Alternatively, Schrum et al. included momentum conservation principles to determine a modified critical length. The modified critical length determined via this method was then used in the existing AASHTO LRFD BDS yield-line resistance equation.

The relationship underpinning this method is expressed in Equation 35. In the arrest of the vehicle’s motion, the initial impact severity is transformed into barrier strain energy and internal energy (IE) within the vehicle. The strain energy (SE) was estimated as the product of the external force and the displaced distance of the barrier.

| (35) |

External force was considered equal to the maximum force the barrier could resist as a function of its flexural resistances:

| (36) |

where L is the activated length of the barrier. Displacement was determined by assuming 6% reinforcement strain, which was selected because it corresponds with the onset of strain hardening in tensile tests of rebar. This assumed deflected shape, shown in Figure 50, results in a lateral displacement of

| (37) |

To estimate the strain energy imparted to the barrier, the resistance of the barrier (Equation 36) is multiplied by the lateral deflection of the barrier (Equation 37).

| (38) |

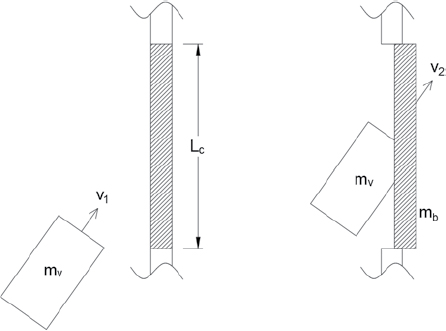

Momentum conservation was used to estimate the change in the vehicle’s internal energy throughout the impact sequence. Initially, the total momentum of the system would be equal to the momentum of the vehicle. After impact, if the collision is assumed to be plastic, the vehicle and a portion of the barrier move together with a terminal momentum related to the activated barrier mass. This relationship is expressed in Equation 39:

| (39) |

where vf is the final velocity of the two-object system, vi is the initial velocity of the vehicle, mv is the mass of the vehicle, and mb is the activated inertial mass of the barrier.

Schrum et al. (2016) suggested that the length of the barrier set into motion is equal to the critical length, Lc, as demonstrated in Figure 51.

With this assumption, the activated mass can be estimated via Equation 40:

| (40) |

where ρc is the density of the concrete, A is the cross-sectional area of the barrier, and Lc is the activated length of the barrier. The final velocity of the vehicle, then, is

| (41) |

in which γc is the unit weight of the concrete, assumed as 150 pcf, and Wv is the weight of the vehicle. With the initial and terminal vehicle velocities estimated, an estimate for the change in the kinetic energy of the vehicle, which is theoretically equal to the change in the vehicle’s internal energy, can be expressed as

| (42) |

The governing equation, then, is expressed in Equation 43. Schrum et al. (2016) recommend the relationship is solved for the critical length, Lc, with a numerical solver. The critical length determined via this relationship is then used in the traditional yield-line resistance equation.

| (43) |

This modified method was validated via computer simulation in LS-DYNA. A simulated TL-4 impact between a safety shape barrier and an SUT was performed, and the change in the vehicle’s internal energy measured in the simulation was compared to the proposed estimate (Equation 42). Measurements were made in the simulation at the point at which longitudinal rebar reached 6% strain. The vehicle’s internal energy as-measured and as-calculated was 11.9% and 13.7% of the impact severity, respectively, indicating good accuracy of the method, provided the assumptions underlying the method are valid. However, the key assumption of 6% rebar strain was challenged in the pushover analysis performed by Cao et al. (2019) in which the maximum rebar strain was just 1%.

Schrum et al. (2016) used the modified critical length to reevaluate the capacities of several existing barriers, which were then compared to the capacities estimated via the traditional method. This comparison is shown in Table 12. Using the modified critical length results in near-universal increases in barrier capacity estimates, though, for most barriers, these increases are marginal. For some barriers, however, such as the TL-5 New Jersey barrier, the T5 bridge rail, and the T201 bridge rail, significant capacity increases were observed. The modified critical length yielded a lower capacity estimate for only one analyzed system, the T202 bridge rail, which is an open concrete rail.

Badiee (2014) presented a similar method where the inertial activation of the barrier is accounted for using conservation of momentum principles. However, whereas Schrum et al. (2016) used the critical length to estimate the activated mass of the barrier, Badiee set the activated barrier based on Lt. Additionally, Badiee calculated the moment of inertia of the barrier about its longitudinal axis to account for rotational inertia effects.

Effect of Impact Height on Capacity

While the traditional and modified yield-line methods differ in their failure patterns and derivations, these methods universally assume that the load is applied at the top of the barrier. However, recent research has shown impact heights to be lower than the total height of the barrier

Table 12. Comparison of traditional and modified capacity estimates (Schrum et al. 2016).

| Class | Barrier Type | H (in.) | Mb (k-ft) | Mw (k-ft) | Mc (k-ft/ft) | Existing Rw (kips) | Modified Rw (kips) | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL-4 | Vertical | 42 | 59.7 | 38.8 | 13.1 | 166.3 | 175.6 | 5.6% |

| 1-Slope | 32 | 0 | 15.1 | 31.3 | 170.6 | 173.0 | 1.4% | |

| F-Shape | 42 | 0 | 18.0 | 21.2 | 139.9 | 148.9 | 6.4% | |

| New Jersey | 32 | 0 | 8.0 | 11.6 | 71.8 | 76.3 | 6.3% | |

| 36 | 0 | 7.2 | 11.6 | 66.9 | 69.5 | 3.9% | ||

| 42 | 0 | 7.5 | 11.6 | 65.4 | 67.6 | 3.4% | ||

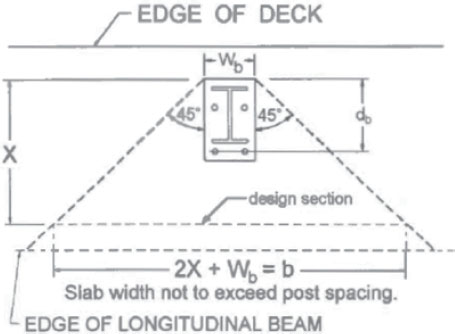

| TL-5 | Vertical | 42 | 59.7 | 38.8 | 13.1 | 185.4 | 187.4 | 1.1% |