Transporting Freight in Emergencies: A Guide on Special Permits and Weight Requirements (2024)

Chapter: 4 Harmonization and Coordination of Special Permitting for Overweight Divisible Loads

CHAPTER 4

Harmonization and Coordination of Special Permitting for Overweight Divisible Loads

Introduction

In the context of truck permitting offices and state agencies’ response to emergencies and disasters, the time to prepare through harmonization and coordination is before the event takes place. These offices and agencies can develop comprehensive emergency commodity lists, detail the specific goods required for various emergencies, and simultaneously initiate the creation of MOUs with neighboring states and relevant agencies. These MOUs should define roles, responsibilities, and regulations related to the transportation of emergency commodities, aligning with the developed lists. A proactive approach enables streamlined processes; minimizes confusion; and ensures an efficient, coordinated response to emergencies, ultimately saving valuable time and resources and promoting regional collaboration.

Development and Evaluation of Emergency Commodity Lists

A truck permit-issuing office’s definition of emergency and emergency commodities is the definition that is contained in the state’s declaration implementing special permitting. For permitting offices, involvement in specifying the language used in the declaration or specifying emergency commodities varies by state. For states adopting more restrictive models of special permitting, there is an opportunity to develop and evaluate an emergency commodity list for preparedness before the emergency.

Although there is no single generic list of emergency commodities, and the commodities needed depend on the nature of the emergency, several state-level emergency declarations resulting in special permitting for divisible loads on state roads have included commodity-specific restrictions, usually related to harvests or a particular commodity shortage, like fuel, heating oil, or propane.

For more generalized disasters or emergencies, like pandemics, hurricanes, or floods, misunderstandings among carriers and enforcement officers exist in regard to the commodities covered by the declaration and the permits. States should be on the lookout for abuse of the special permitting process to move overweight divisible loads that may not otherwise qualify as emergency supplies and communicate appropriate information to state enforcement officials.

The following suggestions are based on the best practices that were identified during this project. An approach toward developing and evaluating the commodity list can be based on the following three-step process:

- Step 1: Understand the nature of the emergency and related needs (i.e., commodity-specific emergency versus diverse-commodity emergency).

- Step 2: Develop a list of commodities needs based on the understanding of the final usage.

- Step 3: Evaluate the commodity list.

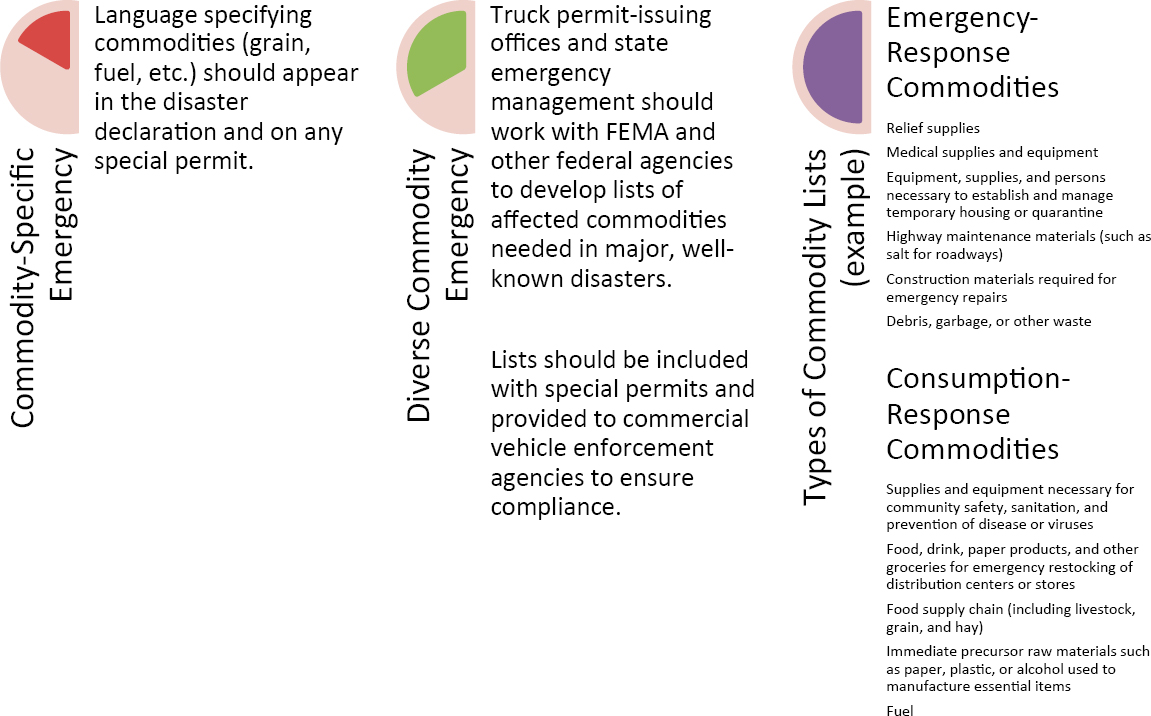

For Step 1, with emergencies affecting specific commodities (e.g., grain and fuel), language specifying those commodities should appear in the disaster declaration and on any special permit. Whereas, for emergencies or disasters requiring a diverse mix of commodities in divisible loads, truck permit-issuing offices and state emergency management should work with FEMA and other federal agencies to develop lists of affected commodities needed in major, well-known disasters (like hurricanes or wildfires); those should also be included with special permits and provided to commercial vehicle enforcement agencies to ensure compliance.

For Step 2, commodities can be divided into two categories, emergency-response commodities and consumption-response commodities. The list can be developed based on the needs; if commodity-type overlaps between these two categories, the commodity can be prioritized based on immediate need before adding to any one of these categories.

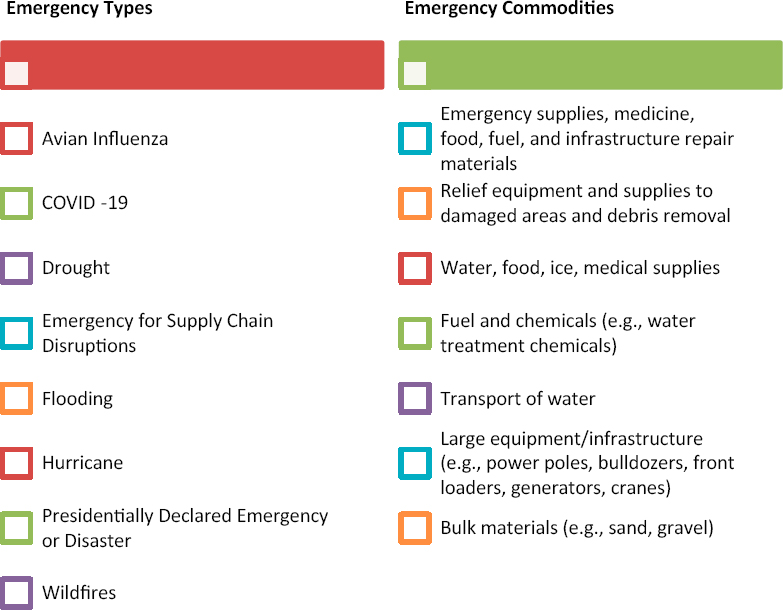

For Step 3, one approach can be to have subject matter experts and officials from nearby states evaluate the commodity list against parameters selected by state agencies to avoid any confusion and potential abuse of the special permitting process to move overweight divisible loads that may not qualify as emergency supplies. These parameters can be selected by truck permitting agencies based on the state or regional agencies’ approach (permissive or restrictive as discussed in Chapter 2) and concerns regarding the risks. Figure 6 and Figure 7 provide examples of developing a list of emergencies and emergency commodities based on the steps described. The lists of emergencies and emergency commodities provided in these figures are not comprehensive and are only a small sample from the data and information collected during this project. The stakeholders and decision-makers may want to develop their own comprehensive list, but they can use this as a starting point.

Considerations for Harmonization and Raising Weight Limits During Emergencies

While harmonization efforts exist across the United States to implement more uniform practices for OS/OW permitting and marking and escort requirements, states issue these permits differently or do not use the same type of agency for permitting. Furthermore, although weight limits for the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways are uniform because of compliance clauses designed to maintain compliance under USCs (e.g., 23 USC 127) and, therefore, prevent any loss of federal highway funding, state highway weight limits vary widely. Consequently, even if a state harmonizes its escort, marking, or lighting requirements with another state, the permitting process and the limitations on state roads may still vary. Additionally, county and municipal governments may require, or attempt to require, their own limitations on county or municipal roadways.

The use of regional MOUs during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates a proactive approach to interstate cooperation and the importance of adaptive regulatory frameworks in response to rapidly evolving challenges. For instance, MAASTO states have already harmonized their emergency divisible loads (EDLs) by signing an MOU. The purpose of this MOU is to establish a minimum EDL permitted weight that all 10 MAASTO states can agree to and adopt. As stated in the MOU, in case of a major disaster declaration under the Stafford Act and corresponding state declaration, this MOU creates a MAASTO regionwide EDL management policy. See Appendix B for the MAASTO agreement.

Following are advantages and potential considerations associated with such regional MOUs, using the MAASTO’s harmonization of EDLs as a case study:

- Efficiency in disaster response: A pre-established MOU allows states to rapidly respond to emergencies without getting entangled in bureaucratic hurdles. The ability to quickly move resources across state lines is crucial in times of crisis.

- Consistency and clarity: A harmonized weight limit across the MAASTO states ensures consistency in regulations. Trucking companies and logistics providers can plan their routes and loads more effectively knowing they will not face different regulations as they cross state lines.

- Collaboration: The MOU fosters a spirit of collaboration among states. This promotes mutual aid and facilitates the sharing of best practices, leading to improved responses in the future.

- Flexibility: The activation of the MOU based on major disaster declarations, such as under the Stafford Act, provides flexibility. It allows for the MOU to be operative only when truly needed, ensuring normal regulatory processes are not unnecessarily disrupted.

Developing MOUs

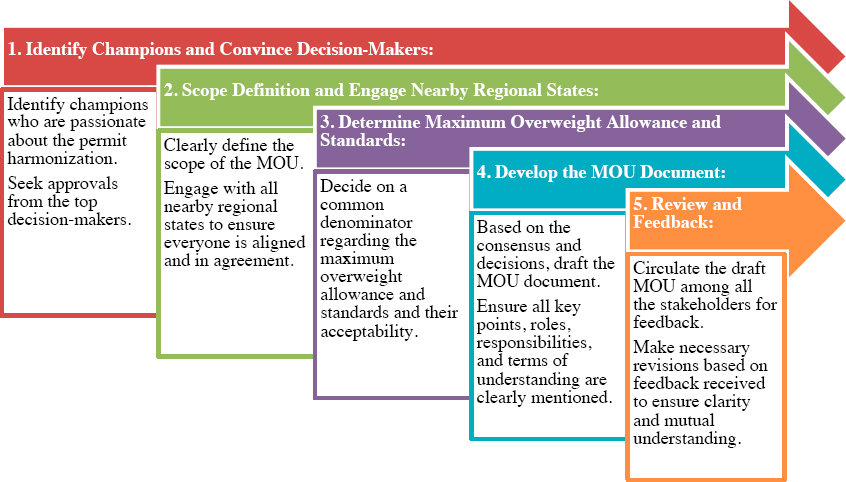

Before any potential crises arise, it is critical for states to initiate coordination. Being proactive means that in the face of a disaster or emergency, there is no delay caused by bureaucratic hurdles, allowing for swift and decisive planning and action. Hence, drafting of the MOU document should be undertaken before the emergency or disaster, ensuring it is comprehensive; details key points, roles, responsibilities; and outlines terms of understanding. Based on the feedback from various stakeholders, the following steps (see Figure 8) assist in developing a robust MOU.

- Step 1: Identify internal and regional champions passionate about the permit harmonization during emergencies; these individuals will be the driving force behind the MOU. Next, secure approvals from the top decision-makers, making certain they grasp the benefits and the importance of the MOU.

To convince the decision-makers, develop persuasive evidence or highlight case studies showing benefits and advantages of the MOU, emphasizing saving time, money, and other resources. A good starting point can be the MAASTO MOU that has led to coordination among 10 states. Additionally, addressing and dispelling any misconceptions or reservations they might have will be beneficial.

- Step 2: At a minimum the MOU’s scope should be well defined, highlighting its applicability specifically to state roads and excluding interstates. As an example, the MAASTO MOU is provided in Appendix B.

- Step 3: As the development process of the MOU evolves, engage neighboring regional states to ensure alignment and foster mutual understanding, ownership, and collaboration. A critical part of developing an MOU is determining the maximum overweight allowance and standards in deciding a common figure that all states intending to participate find acceptable.

- Step 4: Based on the consensus and decisions from the previous steps, draft the MOU document. Ensure all key points, roles, responsibilities, and terms of understanding are clearly mentioned.

- Step 5: Once the draft is ready, disseminate it among stakeholders for feedback. Revisions are made based on this feedback to ensure absolute clarity and mutual understanding. After refining the document and achieving consensus, obtain the final approval. Next, representatives from each state affix their signatures, making the MOU official.

The next phase is the broad dissemination of the finalized MOU to all pertinent departments and officials in the signatory states. It is crucial not only that the MOU’s provisions are on paper but also that they are implemented rigorously. As with all such agreements, a regular review mechanism is essential to ensure the MOU remains relevant and effective. Any required updates, stemming from evolving circumstances or feedback, should be incorporated promptly. Periodically review the MOU to ensure its relevance and effectiveness, and update the MOU as needed based on changing circumstances, requirements, or feedback from stakeholders.

Some considerations and potential challenges with developing MOUs include the following:

- Balancing state sovereignty and regional collaboration: States may be wary of ceding too much regulatory control to a regional body. It is essential to strike a balance between regional harmonization and preserving states’ rights to regulate their own affairs.

- Regular updates: The MOU and its associated regulations may need periodic reviews and updates to ensure they remain relevant and effective. What works now might not work in a decade, given changing technology, infrastructure, and emergencies.

- Communication channels: It is crucial to maintain clear and open communication channels between the participating states. Miscommunication could undermine the effectiveness of the MOU.

- Overreliance: While MOUs provide a framework for collaboration, states should not solely rely on them. Individual state preparedness and resilience building are equally critical.

In conclusion, regional MOUs like the one adopted by MAASTO states represent a forward-thinking approach to disaster preparedness and response. While they offer numerous advantages, it is also important to be aware of the challenges and ensure the MOUs are living documents, regularly updated to meet the evolving needs of the region.