Enabling 21st Century Applications for Cancer Surveillance Through Enhanced Registries and Beyond: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: Proceedings of a Workshop

Proceedings of a Workshop

WORKSHOP OVERVIEW1

Population-based cancer surveillance plays a pivotal role in assessing the nation’s progress in cancer control. Cancer surveillance systems collect and analyze information on cancer incidence, morbidity, and mortality. These data help inform cancer research and care interventions aimed at reducing the burden of cancer on patients, families, and communities, including the ability to identify differences in cancer outcomes. The data are crucial for identifying emerging trends in health outcomes, prioritizing potential avenues for future research, allocating resources to areas of unmet need, and suggesting potential opportunities to improve the quality of cancer care. However, current systems of cancer surveillance face challenges with data timeliness and completeness for analyses and keeping the infrastructure and workforce at pace with the rapid advances in informatics and cancer treatment (Jones et al., 2021).

To examine these challenges, the National Cancer Policy Forum of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine hosted a public workshop titled Enabling 21st Century Applications for Cancer Surveillance

___________________

1 This workshop was organized by an independent planning committee whose role was limited to identification of topics and speakers. This Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the rapporteurs as a factual summary of the presentations and discussions that took place at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants and are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

Through Enhanced Registries and Beyond on July 29 and 30, 2024. Lisa Richardson, director of the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and co-chair of the workshop planning committee, introduced the workshop as an opportunity to explore opportunities to enhance and modernize cancer surveillance to improve cancer research, care, and outcomes for all patients. Robin Yabroff, scientific vice president of Health Services Research at the American Cancer Society and workshop co-chair, said discussions would focus on opportunities to improve the timeliness, quality, and completeness of cancer registry data.

This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the workshop presentations and discussions. Observations and suggestions from individual participants are discussed throughout the proceedings, and highlights are presented in Boxes 1 and 2. Appendixes A and B include the Statement of Task and workshop agenda, respectively. Speaker presentations and the workshop webcast have been archived online.2

PERSPECTIVES ON THE CURRENT STATE OF CANCER SURVEILLANCE

Patient Perspectives

Kelly Shanahan, director of research at Metavivor, a physician, and a person living with metastatic cancer, highlighted the importance of cancer surveillance for improving patient care and the need for cancer registry databases to be representative of all patients in the United States. When Shanahan was diagnosed with Stage 2 breast cancer in 2008, she chose bilateral mastectomy over lumpectomy and weeks of daily radiation therapy because the closest oncology services were a 45-minute drive from her home. She also continued working at her obstetrics/gynecology practice during chemotherapy. In 2013, she experienced severe back pain but dismissed it as a pulled muscle or herniated disk. However, several months later, scans revealed widespread bone metastases and several fractures.

Shanahan said people living with metastatic cancer often feel they are not captured in national databases that provide information on cancer statistics that drive efforts to reduce the cancer burden. For example, she explained that the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) collects cancer incidence and survival data

___________________

2 https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/41759_01-2024_enabling-21st-century-applications-for-cancer-surveillance-through-enhanced-registries-and-beyond-a-workshop (accessed October 8, 2024).

from some population-based cancer registries but does not cover the entire U.S. population. As a result, large regions of the country are currently not counted in the SEER data, rather data are reported to other central cancer registries. Shanahan noted that initial breast cancer diagnoses are generally based on pathology. However, metastatic recurrence is often diagnosed by imaging and the recurrences of patients who are diagnosed with metastases after an early-stage breast cancer diagnosis are not measured. She suggested that to track these cases, it would be essential to establish an International Classification of Diseases (ICD)3 diagnosis code for metastatic recurrence following a primary cancer diagnosis, as they are not currently counted. Also, it would be important to be able to link a patient’s recurrence with their early-stage diagnosis in the registry, she said. “I want to be counted,” she concluded.

Sarah Greene, independent consultant, cancer researcher, and patient advocate, shared that she was diagnosed with Stage 3 endometrial cancer in 2022 and that following surgery, chemotherapy, and continuing immunotherapy, she has had no evidence of disease for 18 months. She attributed her successful outcome to “outstanding guideline-based care.” And while evidence-based guidelines are largely informed by clinical trials, she said they are also “tethered to the comprehensive surveillance data.”

Given the lag time for registration of cancer cases, Greene speculated that she was likely not yet a data point in SEER, but she emphasized that, like Shanahan, she wants to be counted and her data to be used for research. As a researcher, she has experienced the challenges of integrating data from different sources, and while there has been some progress toward harmonization, “we still have a really long way to go,” she said. She explained that there is significant investment in developing novel cancer treatments, but it is challenging to gather outcomes data at a population level, including data on recurrence, treatment side effects, and longer-term outcomes. Greene emphasized that “every data point is a person who has gone through this terrible disease.” She proposed a role for patient advocacy in driving the needed changes in cancer registration and highlighted the importance of “putting a human face” on the role of cancer registries to make a persuasive value proposition to policy makers and decision makers, health systems, industry, health care payers, and other relevant parties for addressing the structural barriers to cancer surveillance and research.

___________________

3 See https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases (accessed October 10, 2024).

Opportunities and Challenges for Improving Cancer Surveillance and Registries

Panelists from NCI, CDC, the American College of Surgeons, and the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) provided background on their respective databases and discussed opportunities and challenges for improving cancer surveillance and registries.

Douglas Lowy, principal deputy director of NCI, presented data to illustrate the need for more comprehensive cancer registries. One analysis that used SEER data led to a conclusion that reductions in cancer mortality were associated, in part, with treatment advances (Howlader et al., 2020). However, an important limitation of the study, Lowy said, was that the main conclusion was entirely inferential because SEER does not include data on patient treatment or response.

Lowy offered four approaches for improving cancer surveillance, by enabling it to be

- more comprehensive, by collecting patient-level data on cancer prevention, screening, treatment, and survivorship and linking the data to enable studies of outcomes;

- timelier, by striving to include real-time, patient-level diagnosis, treatment response, and recurrence data;

- a major source for real-world data; and

- a source of detailed data about molecular characteristics, imaging, and other features.

Lowy emphasized that for each of the approaches, the collection of detailed, patient-level data is essential for quality improvements and inferences based on real-world data.

The National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program

The NCI SEER Program4 was established in 1973 “to support research on the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of cancer,” said Lynne Penberthy, associate director of the Surveillance Research Program at NCI and director of the SEER Program. Cancer reporting to state registries is required of all cancer care providers and exempt from privacy regulations promulgated under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). SEER receives about 900,000 incident cases annually from 18 population-based cancer

___________________

4 See https://seer.cancer.gov (accessed October 11, 2024).

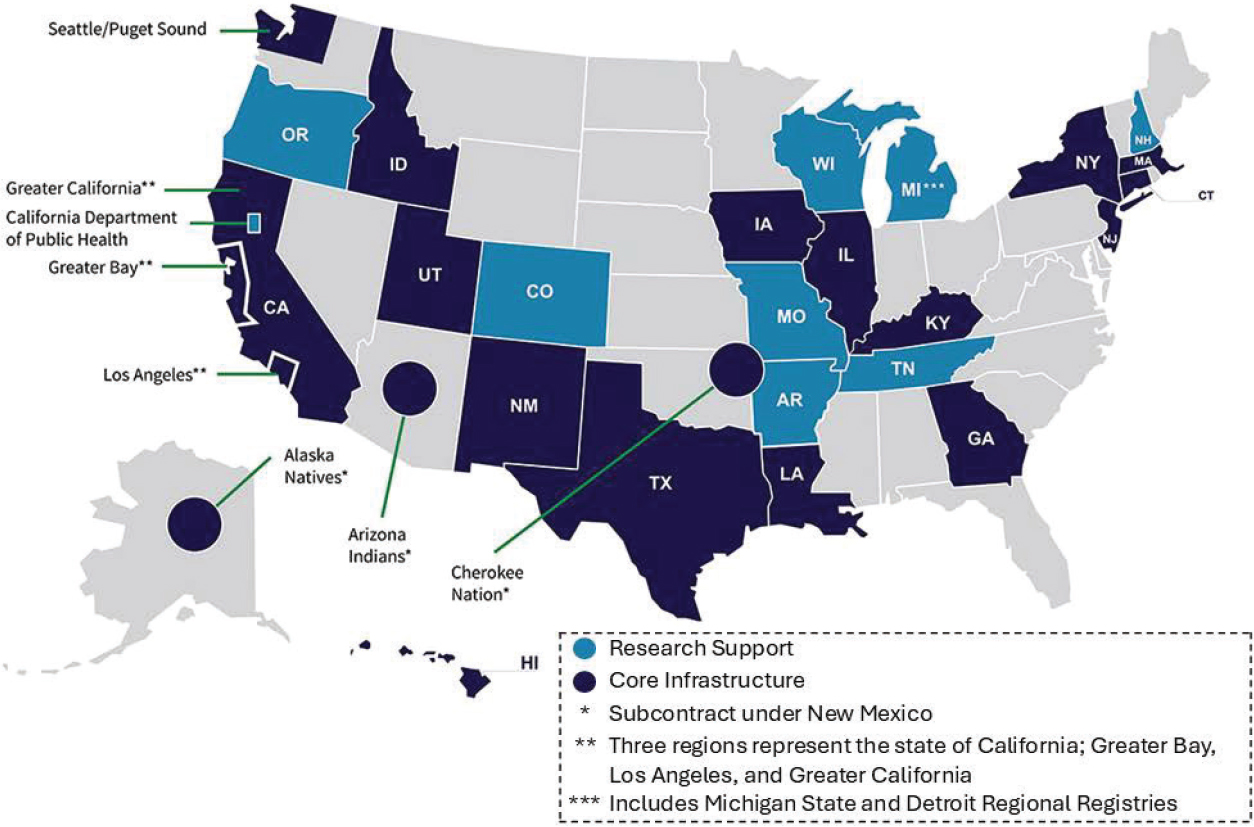

registries covering 48 percent of the U.S. population (see Figure 1) (Penberthy and Friedman, 2024). Penberthy noted that registries submit de-identified data to the SEER Data Management System,5 a central database that can help with facilitating data linkages. In addition to collecting data from the patient’s electronic health record (EHR), SEER taps up to 35 other data sources to inform the patient’s case record. These include medical claims data; pharmacy data; clinical trial information; pathology, imaging, genomic, and genetic results reports from specialty services; and nonmedical data sources, such as motor vehicle administration, veteran, and Social Security information.

Penberthy described some challenges experienced by population-based registries, such as SEER and the CDC National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR). These challenges include the rapid advancement and increasing complexity of how cancer is diagnosed and treated, the lack of data outside of clinical trials on the dissemination and use of new cancer diagnostics and treatments and their impact on patient outcomes, and the lack of access to the full patient health record across multiple potential cancer data sources. She noted that treatment guidelines are frequently based on data from clinical trials, which include only about 5 percent of the population of adult patients with cancer (Unger et al., 2016). She added that these limited, often non-representative, datasets impact the generalizability of treatment guidelines to real-world use. She also emphasized the need for rapid and efficient collection of population-level data.

Penberthy said that a strength of cancer registries is their general ability to adapt as clinical care evolves. For example, SEER is expanding to include genomic and genetic data and information on treatments and social determinants of health. However, the manual collection of data remains a limitation of registries in many cases, and accessioning and reporting can be slow, with complete and finalized registry data running 2–3 years behind diagnoses, she said.

Penberthy agreed with Shanahan that population-level data on recurrent metastatic cancer are lacking. She explained that surveillance of metastatic disease is challenging because diagnoses of recurrence are made across a wide range of care specialties, clinical settings, and diagnostic modalities. Overcoming these challenges will require a multimodal approach, Penberthy said. She suggested that one potential near-term practical solution is a SEER Program collaboration with the Department of Energy (DOE) to develop the Modeling Outcomes using Surveillance Data and Scalable Artificial Intelligence for Cancer (MOSSAIC) project,6 an application programming interface (API) that can capture data on metastatic recurrence from pathology reports (Hsu et al., 2024). Penberthy added that one potential policy approach to improving

___________________

5 See https://seer.cancer.gov/seerdms (accessed October 11, 2024).

6 See https://computational.cancer.gov/about/mossaic (accessed October 20, 2024).

SOURCES: Penberthy presentation, July 29, 2024; SEER, 2024.

surveillance data collection could be linking reimbursement by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to clinician reporting of disease status for each outpatient encounter.

CDC National Program of Cancer Registries

The NPCR was established in 1992 by the Cancer Registries Amendment Act,7 which authorized CDC to provide funding to support state cancer registries, said Vicki Benard, chief of the Cancer Surveillance Branch at CDC. The legislation was introduced8 in response to public demands because Vermont had one of the highest U.S. breast cancer mortality rates. At the time, many states did not have population-based registries, and some states, including Vermont, did not have any cancer registries.

The NPCR currently supports cancer registries in 46 states, Washington, D.C., and three U.S. territories, which Benard said covers 97 percent of the U.S. population (NCCDPHP, 2024). Benard added that some registries are co-funded by both NPCR and SEER, and NPCR and SEER together collect and disseminate cancer surveillance data for the entire U.S. population.

Benard highlighted that one challenge for the NPCR is the several-year lag time between submitting new cancer diagnoses to registries and including that data in national reports. She said that this lag time limits the utility of these data for timely decision making. She added that many cancer registries are working with outdated systems, and many also lack sufficient information technology (IT) support to consolidate the volumes of data submitted. To facilitate more timely receipt of incidence data, Benard said that CDC has been focused on national interoperability, including “an infrastructure to transmit cancer pathology reports electronically from laboratories to cancer registries, using Health Level Seven International (HL7)9 standards for health information exchange.” CDC is collaborating with the Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL) to leverage the APHL Informatics Messaging Services (AIMS),10 a national cloud-based infectious disease reporting platform, to facilitate daily cancer pathology reporting from laboratories to state cancer registries. CDC is also working to increase the uptake of electronic protocols

___________________

7 See https://www.congress.gov/bill/102nd-congress/senate-bill/3312 (accessed October 13, 2024).

8 See https://www.congress.gov/bill/102nd-congress/house-bill/4206 (accessed October 13, 2024).

9 HL7 is a set of global standards for the electronic exchange of health information. See https://www.hl7.org (accessed October 8, 2024).

10 See https://www.aphl.org/programs/informatics/pages/aims_platform.aspx (accessed October 11, 2024).

for cancer data reporting. Challenges for real-time data reporting via a cloud platform, Benard said, are that pathology data are often unstructured and in narrative text. Because additional patient information will also be needed, she said, CDC is pilot testing an infrastructure for leveraging EHR data.

CDC’s vision for cancer surveillance is a cloud-based infrastructure11 to streamline the reporting of registry data to a single portal, Benard said. To this end, she said CDC has developed tools to automate processes and a testing site for cloud infrastructure. She added that CDC has worked with the state- and territory-level central cancer registries on data governance and is continuing to work with partners to develop a minimum dataset, additional tools, and pilot projects to ensure the availability of high-quality, timely cancer surveillance data.

The National Cancer Database

The National Cancer Database (NCDB)12 is a nonfederal joint program of the Commission on Cancer (CoC)13 and the American Cancer Society that was established in 1989. Bryan Palis, senior manager and senior statistician at the American College of Surgeons, said that the NCDB drives the development and implementation of evidence-based quality-of-care metrics that are established standards of best practice based on demonstration of survival benefit. Palis described the NCDB as comprehensive, accruing 1.5 million case records per year from more than 1,400 hospitals; detailed, capturing a wide range of data for more than 70 disease sites and covering about 74 percent of U.S. cases; high quality, as accreditation standards for cancer programs from the CoC drive data accuracy; and contemporary, as cancer cases are submitted at least monthly to the Rapid Cancer Reporting System (RCRS).14

“High-quality cancer registry data are essential to accurately assess treatment and outcomes,” Palis said. He explained that standardized abstraction

___________________

11 See https://www.cdc.gov/national-program-cancer-registries/data-modernization/cloud-based-computing.html (accessed October 13, 2024).

12 See https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer-programs/national-cancer-database/ (accessed October 13, 2024).

13 The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC) is a group of professional organizations dedicated to improving outcomes for persons with cancer through the monitoring of comprehensive quality care as well as promoting cancer prevention, research, and education. See https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer-programs/commission-on-cancer (accessed October 15, 2024).

14 See https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer-programs/national-cancer-database/rapid-cancer-reporting-system (accessed October 15, 2024).

processes outlined in the Standards for Oncology Registry Entry manual15 and staging system developed and compiled by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)16 help ensure the quality and consistency of the data submitted to NCDB and used in CoC reports. He noted that more than 90 percent of CoC-accredited programs are compliant with CoC requirements for cancer registry data quality control and timeliness of data submission. A recent evaluation of NCDB quality control procedures found NCDB to have “a high level of case completeness, comparability with uniform standards for data collection, timely data submission, and high rates of compliance with validity standards for registry and data quality evaluation,” Palis said (Palis et al., 2024). NCDB is working to facilitate real-time quality reporting, including its 2020 implementation of the RCRS.17 One of the challenges NCDB is working to address is the limited data on systemic therapy, recurrence, and progression. Although these data might be captured, he said, they are not reported by NCDB due to data missingness and coding variability. Palis suggested data collection might be improved by using synoptic checklists that incorporate a continuum of cancer outcomes (e.g., no evidence of disease, recurrence, and progression).

Lawrence Shulman, professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, provided examples of how NCDB data are used, including for benchmarking. He described the use of NCDB data on Stage 3 breast cancer survival as a metric of quality of care. The analysis found that survival was better at NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers versus large or small community hospitals (Shulman et al., 2018). Shulman said, however, that the data are not sufficiently detailed to determine why this is the case and therefore are of limited use for quality improvement efforts.

Shulman also shared examples of the Cancer Quality Improvement Report18 for the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. The first example compared 30- and 90-day mortality for a particular complex cancer surgery at the University of Pennsylvania versus all CoC programs and high-volume CoC programs, identifying areas for improvement. The second example benchmarked hospital compliance with the quality measure requiring pathology analysis of at least 12 regional lymph nodes for primary colon cancer surgery;

___________________

15 See https://www.facs.org/media/vssjur3j/store_manual_2022.pdf (accessed October 8, 2024).

16 See https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer-programs/american-joint-committee-on-cancer/cancer-staging-systems/cancer-staging-system-products (accessed October 8, 2024).

17 See https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer-programs/national-cancer-database/rapid-cancer-reporting-system (accessed October 13, 2024).

18 See https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer-programs/national-cancer-database/qualitytools (accessed October 15, 2024).

Shulman shared data showing that increased compliance improved survival outcomes across hospital types, and that sharing data with cancer programs was associated with improved compliance over time (Shulman et al., 2019).

CoC-accredited programs can also apply to use NCDB for research, and Shulman noted about 1,300 applications per year. Research use of NCDB has resulted in more than 4,500 publications, and Shulman shared an example that described differences in care for early-onset colorectal cancer that can inform cancer surveillance (Nogueira et al., 2024).

North American Association of Central Cancer Registries

NCI began publishing cancer mortality atlases in the 1970s, which Betsy Kohler, executive director of the NAACCR,19,20 said inspired an increase in cancer registries across the country as states sought to understand their cancer death rates. The mission of NAACCR, a nonprofit, volunteer organization representing the United States and Canada, includes education and training for registries, registry certification, data publication, and promotion of data use for research and public health purposes (NAACCR, 2024). Its certification involves independent assessment of central registry data quality based on objective and measurable criteria for data completeness, timeliness, and quality of reporting (White et al., 2017).

Kohler said that NAACCR also works collaboratively with partners including NCI, CDC, CoC, and the National Cancer Registrars Association (NCRA) to develop cancer surveillance standards. She explained further that within the collaboration, a mid-level tactical group (MLTG)21 focuses on change management and implementation of data standards, while a high-level strategic group (HLSG)22 focuses on collaborative decision making and interagency strategic planning. Standards are updated annually. Kohler said the process of introducing a new data item takes about 18 months and is “incredibly complex” (see Figure 2).

Kohler said population-based cancer registries experience ongoing challenges, including the complexity of collating individual patient data from

___________________

19 See https://www.naaccr.org (accessed October 13, 2024).

20 Betsy Kohler was the executive director of the NAACCR at the time of the workshop. At the time of publication of the proceedings the director is Karen Knight. See https://www.naaccr.org/board-resolutions/#1727105112085-6447aff5-03f1 (accessed December 16, 2024) and https://www.naaccr.org/naaccr-board (accessed December 16, 2024).

21 See https://my.naaccr.org/committee-details?cid=a0O5e000002k6msEAA (accessed October 15, 2024).

22 See https://my.naaccr.org/committee-details?cid=a0O5e000002k6mqEAA (accessed October 15, 2024).

NOTES: API = application programming interface; HLSG = high-level strategic group; MLTG = mid-level tactical group; NAACCR = North American Association of Central Cancer Registries; SSDI = site specific data items; UDS = uniform data standards; WG = working group.

SOURCES: Kohler presentation, July 29, 2024; Hill, 2023.

many different sources to create a high-quality cancer record; decades-old data systems with limited capability for real-time data reporting; under-resourced registries; and state policies that restrict data sharing from and among central registries. Each state has its own set of variables that are mostly derived from other sources such as SEER, NAACCR, and CoC manuals, but they differ in scope and content.

Reflecting on the overview of the current state of cancer surveillance and registries, Yabroff emphasized the need for data collection on cancer progression and recurrence and questioned whether payers could require submission of ICD for Oncology (ICD-O)23 codes for disease status and how those data might then be captured by registries. Shulman agreed that relevant codes are needed to support cancer surveillance and said that “terminology needs to be unambiguous” so clinicians do not waste valuable time hunting for the correct code to enter in a patient record. Penberthy noted that codes for secondary malignancies exist, but they are not always consistently or correctly used. She suggested that an important policy opportunity would be to encourage or enforce the use of these codes in a more accurate way. “A challenge for the use of ICD codes for surveillance is that it would require access to claims data,” she added.

Richardson emphasized the importance of improving data capture with a focus on progression and recurrence in cancer surveillance and registries. She asked about the potential role of artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance data collection. Lowy said that the NCI and DOE MOSSAIC project,24 which aims to develop novel solutions for near real-time disease reporting for cancer by automating the capture of data from unstructured pathology reports, has great potential but also limitations due to curation and quality control concerns. Heidi Hanson, group leader of biostatistics and multiscale system modeling at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory and lead of MOSSAIC, noted the opportunity for AI use in cancer surveillance and registries. However, she also mentioned issues of data scarcity and longitudinal follow-up. She explained that the current AI model works well for unstructured pathology reports, but numerous other potential data sources exist, and to take full advantage of technological solutions, it would be necessary to “link patients at the national level, follow patients longitudinally, and make data available for training of AI models.” Peter Gabriel, associate director of the Penn Center for Cancer Care Innovation at the University of Pennsylvania, also suggested that embedding Oncology Data Specialist (ODS)-Certified cancer registrars in care teams might increase the capture of recurrence data. He acknowledged, however,

___________________

23 See https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/other-classifications/international-classification-of-diseases-for-oncology (accessed October 24, 2024).

24 https://datascience.cancer.gov/collaborations/nci-department-energy-collaboration (accessed October 24, 2024).

that the current workforce of registrars is likely not sufficient to do this. Benard agreed that such an approach would require funding and resources that are not currently available. Penberthy and Shulman also added that not all recurrences are diagnosed in a hospital setting and that the data come from a wide range of sources. Thus, a holistic approach to data collection is needed. Kohler noted that data captured from multiple sources for a single patient could be conflicting because not all data are captured at the same time and would need to be resolved. Penberthy said this is an example of why some level of manual review will always be needed, such as to issue judgment on such conflicts. Furthermore, Eric Durbin, director of the Kentucky Cancer Registry and president-elect of NAACCR, suggested that a national patient identifier would help to facilitate data linkages and solve an array of cancer surveillance challenges, including the capture of recurrence data. Richardson agreed and said this has long been discussed, but concerns about privacy and confidentiality are often raised.

Building on Kohler’s point on state policies that restrict data sharing from central registries, Roy Jensen, William R. Jewell, M.D. Distinguished Kansas Masonic Professor of Cancer Research at the University of Kansas, noted that it would be essential to have model legislation that balances patient privacy protections with the need for health care professionals and researchers to access registry data. Kohler agreed and said that it is difficult to balance population size, privacy, and data utility, and challenges vary by state. Shulman said that some of the programs that report data to NCDB are very small and noted that there are approaches to develop “cohorts” for analyses that ensure data privacy.

LESSONS LEARNED FROM U.S. AND INTERNATIONAL CANCER SURVEILLANCE EFFORTS

Several speakers representing local, state, and international surveillance efforts and end users of registry data shared their perspectives on potential strategies for improving cancer surveillance, including opportunities for multidisciplinary collaboration.

U.S.-Based Perspectives

A Regional Registry Perspective: Greater Bay Area Cancer Registry

Scarlett Lin Gomez, professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and director of the Greater Bay Area Cancer Registry (GBACR) in California, said that the GBACR25 is one of

___________________

25 See https://cancerregistry.ucsf.edu (accessed October 15, 2024).

the nine original registries in the SEER Program (Kohler et al., 2011). After the statewide California Cancer Registry26 was established in 1988, the GBACR was expanded from five to nine counties and is based at UCSF. Gomez shared her perspective on opportunities and challenges for local registries in four areas: data dissemination, data access, data availability and quality, and linkages.

First, data dissemination has evolved from hardcopy reports to interactive online dashboards and maps, which Gomez said provides opportunities for broad dissemination to a wide range of end users. She pointed out that the tools in the California Health Maps27 allow for reporting of data from “more geographically meaningful units,” such as zones comprising similar census tracts. Los Angeles County, for example, is divided into several hundred zones, she said. One challenge, Gomez said, is that “numerator data” are available from the registry, but there is often a lack of timely “denominator data” (e.g., census tract data, detailed population subgroup data such as race/ethnicity) for analysis of cancer trends. Gomez noted that another challenge at the local level is balancing data granularity with data suppression rules for small populations.

Second, there are increasing challenges for registries trying to release data and researchers trying to access data (Iyer et al., 2023). Gomez said that limiting data use slows research progress, and it is unclear whether patients are better protected by restrictive use policies. Gomez said that data access policies vary by state, and she advocated for changes in policies that limit data access.

The third point Gomez raised is data availability and quality challenges. Examples mentioned by Gomez included the high percentage of missing registry data for key elements (e.g., birthplace and Hispanic origin); lack of data on cancer progression and recurrence, health behaviors, and patient sociodemographic information; and variability in data quality and completeness across registries, even within a state (In et al., 2019; Lee and Singh, 2022; Mendez et al., 2024; Montealegre et al., 2014).

Last, Gomez said that data linkages can provide opportunities to fill gaps in data availability. However, linkages are “administratively difficult given [the] need to share patient identifying information,” she added. She suggested there are opportunities to use methods such as privacy protecting record linkage; approaching institutional privacy offices to develop data use agreements with indemnity language as required by states; and engaging patient advocates in conversations about the use of their data.

Despite the challenges, Gomez said that there have been many successes in gleaning new knowledge from cancer registry data (Abrahão et al., 2024; Giannakeas et al., 2024).

___________________

26 See https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CCDPHP/DCDIC/CDSRB/Pages/About-the-CCR.aspx (accessed October 15, 2024).

27 See https://www.californiahealthmaps.org (accessed October 15, 2024).

A Central Registry Perspective: Pennsylvania Cancer Registry

Wendy Aldinger, manager of the Pennsylvania Cancer Registry (PCR), shared her perspective on opportunities and challenges for a central cancer registry. The PCR was established by the Pennsylvania Cancer Prevention, Control, and Research Act of 198028 and has been collecting data statewide since 1985 with funding from NPCR (PCR, 2024).

As an NPCR registry, Pennsylvania had the opportunity to be one of the first states to use the CDC Registry Plus software29 to collect and process registry data and be involved in developing and testing of subsequent Registry Plus components. Pennsylvania also participated in the APHL-AIMS platform initiative discussed by Benard, which Aldinger said has resulted in 22 new laboratories reporting to the registry, with minimal effort on its part. PCR also works closely with the Pennsylvania cancer control program and Pennsylvania Breast & Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program,30 which use registry data to support state cancer control initiatives.

Aldinger said that as PCR is a central registry, its funding has remained level in the face of rising costs. She added that because of the funding challenges, it is difficult to test and implement new technologies, some of which require additional IT support, while keeping up with the registry workload using the current, often manual procedures. There is also the push for real-time data, for which there is also a cost, she said.

A Registry Curator and End-User Perspective: Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center

Stephen Schwartz, co-principal investigator of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center’s Cancer Surveillance System (CSS), provided a perspective as both the head of a local registry and a registry data user. He discussed a successful effort to speed up cancer case ascertainment to improve the CSS and an unsuccessful effort that was aimed at accessing state administrative health data, which could expand what a cancer registry could tell us about the full spectrum of cancer care.

The first effort focused on reducing delays in cancer case ascertainment, both to identify trends more rapidly and take action where possible, and facilitate clinical trial recruitment closer to diagnosis, which he noted is par-

___________________

28 See https://www.legis.state.pa.us/WU01/LI/LI/US/PDF/1980/0/0224..PDF (accessed October 15, 2024).

29 See https://www.cdc.gov/national-program-cancer-registries/registry-plus/index.html (accessed October 13, 2024).

30 See https://www.pa.gov/en/agencies/health/diseases-conditions/cancer/pa-bccedp.html (accessed October 15, 2024).

ticularly important for cancers that are late stage at diagnosis and rapidly fatal. Schwartz explained that presumptive cases for the CSS were first identified through screening of daily, weekly, and monthly hospital electronic pathology feeds. He said that trained staff then used a case-finding software system to determine if a patient was a likely registry candidate based on site, histology, age, sex, and residence. A request to complete a NAACCR abstract was then sent to the hospital. After the abstract was received, a new incidence record was accessioned into the CSS registry. While case finding and accessioning each took only a couple of days, receiving the abstract from the hospital could take weeks to months, he said. To address this, it was determined that the core data needed to confirm an incident case were available after case finding, and it could then be accessioned into CSS for use in surveillance and research, while the NAACCR abstract was being completed. As a result, Schwartz said, cases from the institutional electronic pathology feeds can now be available in CSS within a week.

Schwartz also described the effort to access state administrative health data, particularly All-Payer Claims Databases31 and hospital discharge databases, to expand the scope of the registry content. Relevant information in these databases include data on diagnostic modalities and treatments, the health of cancer survivors, and payments (which could be used to estimate costs of care). This effort has not been successful, as access to the Washington State All-Payer Claims Database is “substantially limited by state regulation,”32 he said. Access is available only for “circumscribed research projects.” Use for public health surveillance is not permitted, and data may not be rereleased (and therefore could not be reported to or made available via external linkages to NCI or CDC databases). Schwartz added that the state cancer registry also cannot access these data, and lack of access impacts other disease surveillance efforts.

A Registry End-User Perspective: Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute

The Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI)33 is part of the Health Care Systems Research Network (HCSRN),34 a consortium of research centers at 20 U.S. health care systems, said Jessica Chubak, senior investigator at KPWHRI. “Each research center has a similarly structured data

___________________

31 See https://www.ahrq.gov/data/apcd/index.html (accessed October 13, 2024).

32 See https://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=43.371.020 (accessed December 16, 2024).

33 See https://www.kpwashingtonresearch.org (accessed October 15, 2024).

34 See https://hcsrn.org (accessed October 15, 2024).

warehouse with many different types of comprehensive health and health care data,” she said. Although the sources of cancer data might be different across health care systems (e.g., internal cancer registry versus external data sources), data in each research center’s HCSRN virtual data warehouse are saved in a common structure. Chubak said Kaiser Permanente Washington collaborates with the Seattle-Puget Sound Registry,35 the SEER registry at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center.

Chubak offered two proposals to advance registry-based cancer research from her perspective as an end user of registry data. First, Chubak proposed easing data sharing restrictions, as other speakers had already suggested. She said that linkages between registries and health care systems data are critical for cancer research and that broader access to registry data by health systems could improve research efforts.

Chubak’s second proposal was to require and fund the inclusion of recurrence in cancer registries. She listed several overarching challenges for collecting such data, including distinguishing recurrence from progression; the ability to follow a patient over time and across health systems, payers, and geographies; the accuracy of data collection methods; and cost. She suggested that a multipronged approach to recurrence data collection is needed, with likely no “one-size-fits-all” solution. Funding and regulatory barriers will need to be addressed for any solution, she concluded.

International Perspectives

Cancer Data, Registries, and Surveillance in Canada

Craig Earle, chief executive officer of the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC),36 shared a perspective on cancer surveillance in Canada. He noted that health care is under provincial jurisdiction in Canada, and CPAC is a federally funded organization tasked with advancing a pan-Canadian cancer strategy in collaboration with provinces and other partners (CPAC, 2024). One area of focus for CPAC is improving cancer data.

Each of the 13 provincial jurisdictions has a cancer registry that reports data to a central Canadian registry (Statistics Canada, 2024). Earle said cancer staging was not routinely entered into most cancer registries in Canada about two decades ago, so one of CPAC’s initiatives was to introduce staging, through first the Collaborative Stage system and later the AJCC staging sys-

___________________

35 See https://seer.cancer.gov/registries/sps.html (accessed October 15, 2024).

36 See https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca (accessed October 16, 2024).

tem.37 Cancer stage is now captured by registries across Canada, but challenges persist. The AJCC standards are frequently updated. The process is “time, training, and resource intensive,” Earle said, and as a result, “many jurisdictions only stage select cancer sites.” To improve capture of cancer stage, CPAC supported two synoptic reporting initiatives, one for collection of pathology and surgical data and another in which communities of practice would use synoptic data for quality improvement (Arnaout et al., 2024). Although synoptic reporting of pathology data has been adopted across Canada, Earle said neither synoptic surgical reporting nor the communities of practice for quality improvement were sustainable.

Cancer data are also needed for cancer system performance reporting, and from 2008 through 2018, CPAC issued annual reports comparing cancer system performance across jurisdictions (CPAC, 2018). However, there were concerns about the resources required within the jurisdictions for this process and varying opinions about the benefit of making such comparisons, Earle said. In 2018, the approach was changed to “monitoring jurisdiction-specific progress towards the priorities of the Canadian Strategy for Cancer Control,”38 but he added that there has been recent interest in again reporting on cancer system performance.

Furthermore, Earle said that the ability to link cancer registries to other data sources in Canada varies across provinces. In Ontario, for example, ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences)39 has an advanced virtual data warehouse. Similarly, through Statistics Canada,40 the Canadian Cancer Registry has been linked with sources of social determinants of health data (e.g., individual tax files, immigration data, and census data).

In 2023, CPAC and the Canadian Cancer Society41 released the Pan-Canadian Cancer Data Strategy.42 Earle said interested parties, including health administrators, researchers and academic institutions, as well as federal, provincial, and territorial policy makers, were engaged in an iterative process

___________________

37 The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system uses TNM, which is a global system that evaluates cancer through Tumor (e.g., size, spread), lymph Node spread, and Metastases. The Collaborative Stage system was a combination of TNM, SEER Extent of Disease, and SEER Summary Stage data that is no longer in use. See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/ajcc-staging-system and https://seer.cancer.gov/tools/collabstaging (accessed October 13, 2024).

38 See https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Canadian-Strategy-Cancer-Control-2019-2029-EN.pdf (accessed October 13, 2024).

39 See https://www.ices.on.ca/our-organization (accessed October 16, 2024).

40 See https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/start (accessed October 13, 2024).

41 See https://cancer.ca/en (accessed October 16, 2024).

42 See https://dev.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/about-us/corporate-resources-publications/pan-canadian-cancer-data-strategy (accessed October 8, 2024).

to identify data gaps and establish funding priorities, such as improving the efficiency, timeliness, and quality of data capture and access; enhancing linkages to current data; and filling gaps in current data collection.

Cancer Surveillance and Registries in Europe

Europe has 180 population-based cancer registries across 41 countries, covering about two thirds of the population of Europe (Arndt and Siesling, 2024), said Volker Arndt, director of the Baden-Württemberg Cancer Registry and head of the Unit of Cancer Survivorship at the German Cancer Research Center or Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ).43 “Registration practices differ, and harmonization is a key task of the European Network of Cancer Registries,”44 he said, adding that the European Commission has recently committed €13 million to support quality improvement of European cancer registry data. Arndt shared his perspective on cancer surveillance and registries based on his experience with cancer registration in Germany.

Arndt said that prior to the Federal Cancer Registry Act in 1995,45 Germany had only a few cancer registries (Robert Koch Institute, 2016). By 2009, all states had registries (Robert Koch Institute, 2019). Additional legislation followed in 2009, addressing the collection and sharing of harmonized data at the federal state-level;46 in 2013, enabling quality assurance through registries;47 in 2021, addressing access to cancer registry data;48 in 2022 a call was launched to leverage AI to enhance the use of registry data;49 and, in 2024, addressing linkage of cancer registry and other data for research use.50 Arndt said that Germany now has 15 federal state-level cancer registries and one nationwide childhood cancer registry. “All data are pooled at the national level,” Arndt added (Katalinic et al., 2023).

___________________

43 See https://www.dkfz.de/en/krebsregister/index.html (accessed October 16, 2024).

44 See https://encr.eu (accessed December 16, 2024).

45 The Federal Cancer Registry Act was passed in Germany parliament in November 1994 and was in effect from 1994 to 1999. See http://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzeiger_BGBl&jumpTo=bgbl194s3351.pdf (accessed November 23, 2024).

46 See https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bkrg (accessed November 23, 2024).

47 See http://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzeiger_BGBl&jumpTo=bgbl113s0617.pdf (accessed November 23, 2024).

48 See http://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzeiger_BGBl&jumpTo=bgbl121s3890.pdf (accessed November 23, 2024).

49 See https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/ministerium/ressortforschung/handlungsfelder/forschungsschwerpunkte/krebsregisterdaten.html (accessed November 23, 2024).

50 See https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/gdng (accessed November 5, 2024).

Arndt highlighted some of the key characteristics of population-based cancer registration in Germany, including a comprehensive data catalog of more than 130 items spanning tumor information, primary and subsequent treatment, recurrence and progression, genetics, and other information.51 He said that reporting is mandatory for clinicians involved in the treatment of the patient’s cancer and patient consent is only required for follow-up contact for future research purposes, such as recruitment of survivors to obtain further information. Additionally, data can be exchanged between states, allowing for longitudinal tracking of patients who move or receive care in a different state. Arndt said that clinicians receive a financial incentive for reporting (Katalinic et al., 2023). He added that an approach to capturing patient-reported outcomes is in development.

Arndt also discussed several examples of the applications of population-based cancer registry data, such as tracking quality indicators of cancer care (e.g., for a particular type of cancer or by type of hospital); understanding the patient experience (e.g., travel distance to treatment and willingness to travel further for a certified cancer center); and studying real-world outcomes (e.g., recurrence rates for a particular cancer relative to treatment and other factors) (Holleczek et al., 2023; Klora et al., 2024; Schulz et al., 2024).

Arndt noted that challenges with cancer registration still persist including data quality (e.g., completeness and timeliness); increased workload for clinicians and registry staff; the need for data validation and harmonization; and costs. The initiative in Germany to leverage AI to enhance the use of registry data and the recently introduced legislation on linking cancer registry data with health insurance data52 could help overcome some of these challenges, he concluded.

DATA COLLECTION METHODOLOGIES AND TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCES IN CANCER SURVEILLANCE

Peter Paul Yu, physician-in-chief of the Hartford HealthCare Cancer Institute and Clinical Member at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK), said that data standards including data dictionaries describing elements of importance for cancer reporting have been developed over decades by multiple organizations such as NPCR, SEER, and NCDB. He noted, however, that these can be specific to each organization’s use cases and do not necessarily align with one another. New data element lists continue to be developed, including

___________________

51 See https://www.basisdatensatz.de/basisdatensatz (accessed October 16, 2024).

52 See https://www.recht.bund.de/bgbl/1/2024/102/VO.html (accessed October 16, 2024).

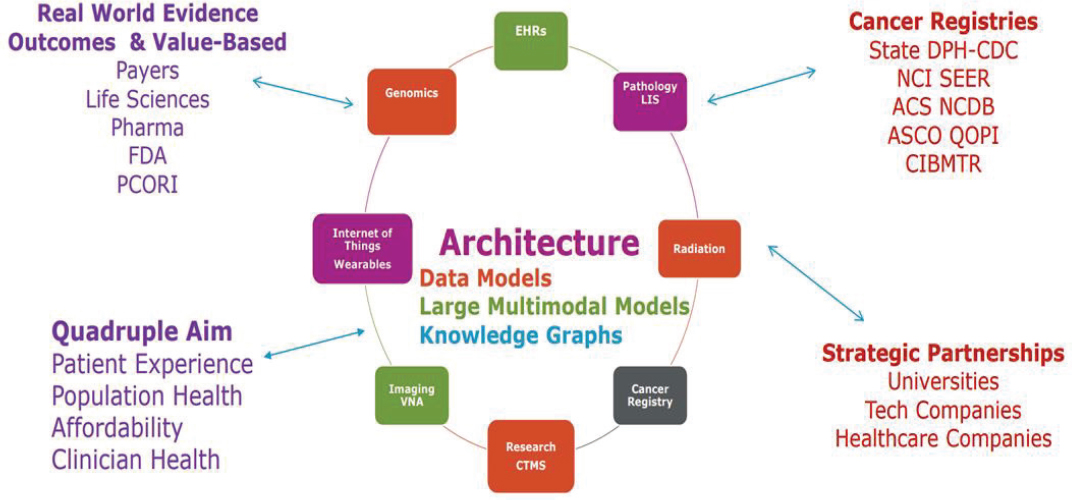

USCDI+53 for cancer, a domain-specific list to accompany the U.S. Core Data for Interoperability (USCDI) dataset54 maintained by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC). Attention is also turning to the need for data elements to describe information derived from omics-based tests.55 The challenges, Yu said, include data capture in both human and machine-readable formats (e.g., structured data entry in EHRs and synoptic pathology reports), harmonization of data dictionaries, and adoption of transmission standards (e.g., state cancer registry capabilities and bidirectional data sharing). There are emerging methods, such as common data models, but he noted that new approaches can be complex, and they could create additional burdens for data entry. There are potential roles for new technologies, such as generative AI, and knowledge graph56 extensions, which can capture relevant data from existing sources (e.g., social determinants of health information from census data). The ultimate goal of capturing data is to inform a learning health care system (see Figure 3) and improve care quality and value, which Yu said involves applying data science and machine learning to high quality digital data to answer key questions.

Many panelists representing a range of organizations involved in data collection and curation for cancer surveillance shared their perspectives on current approaches and emerging tools for automation and analytics.

Curating Real-World Electronic Health Record Data with the Flatiron Health Database

Emily Castellanos, senior medical director at Flatiron Health, said that Flatiron Health curates real-world data from more than 3 million patient records across a network of oncology practices (Castellanos et al., 2024). About three quarters of the network is community oncology practices that

___________________

53 See https://www.healthit.gov/topic/interoperability/uscdi-plus (accessed October 14, 2024).

54 See https://www.healthit.gov/isp/united-states-core-data-interoperability-uscdi (accessed October 16, 2024).

55 Omics refers to any of several areas of biological study defined by investigating the entire complement of a specific type of biomolecule or all of a molecular process within an organism, such as proteomics, metabolomics, genomics, and transcriptomics. See https://www.britannica.com/science/omics (accessed October 14, 2024).

56 Knowledge graphs are models used to organize interlinked concepts to connect data and context, thereby empowering analytics, integration, and human–system interfaces. See https://www.turing.ac.uk/research/interest-groups/knowledge-graphs (accessed October 16, 2024).

NOTES: ACS = American College of Surgeons; ASCO = American Society of Clinical Oncology; CIBMTR = Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research; CTMS = Clinical Trial Management System; DPH-CDC = Division of Population Health-Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; LIS = laboratory information system; NCDB = National Cancer Database; NCI = National Cancer Institute; PCORI = Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; QOPI = Quality Oncology Practice Initiative; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; VNA = vendor neutral archive.

SOURCE: Yu presentation, July 29, 2024.

use Flatiron’s EHR product, OncoEMR,57 and about one quarter is academic medical centers for which Flatiron Health integrates into the local EHR system (Guadamuz et al., 2023).

Real-world data can be found in both structured and unstructured formats in the EHR, Castellanos said, adding that mapping and harmonization of structured data are necessary because formats can vary by site. Much of the real-world data in the EHR is in unstructured documentation (e.g., clinician notes, pathology reports, and radiology reports), which is converted into structured variables through human abstraction, machine learning, and/or natural language processing. Flatiron Health also links to patient data from outside sources, such as genomic data, claims data, socioeconomic status information, Social Security death index data,58 and obituary information, she said (Castellanos et al., 2024).

Castellanos shared an example of the breadth of critical, complex clinical information that can be captured from unstructured data, such as those in imaging or biomarker reports. However, systematic abstraction of unstructured data is resource intensive and requires staff training and standardization of policies and procedures to ensure continuity across organizations and time. Quality assurance is also necessary, including assessing abstractor agreement, assessing and adjudicating discrepant or implausible data, and validating form entries to reduce human error, she said (Castellanos et al., 2024).

Castellanos said that Flatiron is developing machine learning and AI approaches to augment human abstracting. She described one approach that trains the software to use regular expressions59 to find certain phrases to determine how something might be documented in a chart. She said that teams of clinical experts work with the software engineers to inform the training of the machine learning models with selected phrases and labeled abstracted data. She added that “the model learns which phrases indicate metastatic diagnoses based on training examples, from which it will generate predictions.”

Castellanos discussed several challenges for advancing abstraction of real-world data from EHRs. The first is how to ensure data quality for machine learning and AI approaches. Another is determining “the right balance between humans and technology,” and she said that it is unlikely that machine learning extraction will be done without any human involvement. Finally, she raised the question of how to add and quickly scale new variables. “Will there be new techniques which will allow us to scale without having to abstract thousands of patients?” Castellanos queried.

___________________

57 See https://flatiron.com/oncology/oncology-ehr (accessed October 16, 2024).

58 See https://www.ssa.gov/dataexchange/request_dmf.html (accessed October 16, 2024).

59 Regular expressions are specific syntax used to search for terms. See https://www.csfieldguide.org.nz/en/chapters/formal-languages/regular-expressions (accessed December 16, 2024).

The National Cancer Database Rapid Cancer Reporting System for Real-Time Reporting

Palis said that the NCDB invested in the RCRS, a real-time data collection infrastructure, in direct response to feedback from CoC-accredited cancer programs. He said that the programs expressed their need for real-time data to support expedited reporting of key quality of care metrics for benchmarking hospital performance.

Per CoC standards, local registries at CoC-accredited programs now report all newly diagnosed cancer cases to the RCRS at least monthly,60 Palis said. It is also expected that staging, first course treatment,61 and follow-up data will be reported when available, which he said is “an incremental move towards concurrent abstraction.” Palis noted that moving from submission of complete record layout data to incremental reporting with concurrent abstraction is a “fundamental shift in the way that registries operate” and that the American College of Surgeons is developing relevant standards and technology enhancements. He added that the benefits of continued enhancements to the NCDB real-time reporting platform will only be realized if registries have automation tools to reduce their workload.

To improve the accuracy of case submissions, interactive data quality reports provide programs with information on the completeness of reported data for required items. Programs can monitor their quality measure performance “in real-time from data updated daily,” Palis said, and see their rolling performance rate for the prior 12 months. Hospitals can also view their performance benchmarked against others (ACS, 2022). Another enhancement, which will be launched in 2025, is the capability for CoC-accredited programs to create interactive benchmark reports based on real-time data and submit these to NCDB, Palis concluded.

Reconceptualizing Electronic Health Record Data Entry: The Penn Smart Form Documentation Tool

Shulman said that critical patient data are largely in free text, and they are inconsistently reported in EHRs. It is important to recognize that automated data extraction technologies can only extract what is in the EHR, he added. More complete data can also help elucidate why a patient’s clinician

___________________

60 See https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer-programs/commission-on-cancer/standards-and-resources/2020/implementation (accessed October 23, 2024).

61 First course treatment includes “all types of treatment documented in the treatment plan and given to the patient prior to progression of disease or recurrence of disease.” See https://training.seer.cancer.gov/treatment/first-course (accessed December 17, 2024).

has made particular treatment choices. To enhance the content in EHRs, the University of Pennsylvania has developed and implemented an EHR-based documentation tool that prompts the entry of key data in a structured format. Shulman said that “the smart form,” together with cancer staging and routinely collected patient-reported outcomes and other structured data in the EHR (drugs, doses, lab results, etc.) will give a more comprehensive picture of persons with cancer across their care continuum. He emphasized that the form facilitates documentation, does not add work, and need not be reiterated in a free text entry.

Shulman also described a recent study that looked at the impact of payment policies on how clinical information is documented. Clinicians focus on information required for reimbursement, he said, and the result is “poor-quality, low-value documentation that is not structured or computable and contributes to clinician burnout” (Gabriel et al., 2023). The authors proposed a payment approach to reimburse for documenting key data in a structured format.

Lessons From the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium

Jeremy Warner, founding director of the Center for Clinical Cancer Informatics and Data Science at Brown University, said informatics requires people, process, and technology. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the ability to gather timely data on persons with cancer who were diagnosed with COVID-19 was lacking. The people and technology were there, Warner said, but the processes were missing. The COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC19)62 was formed to fill the gap. The consortium now includes 123 institutions and more than 600 investigators.

Warner provided information on some essential elements that needed to be rapidly assembled to launch CCC19, from overall governance of the consortium to committee structures, the data model, terminology, quality metrics, analytics, and outreach and patient engagement. Warner noted that processes were copied from other organizations when possible, and persons with cancer who were experiencing COVID-19 were engaged to inform the development of the database.

Echoing a number of other speakers, Warner said that critical elements needed to populate the CCC19 registry, such as cancer treatment regimens, treatment toxicity, cancer status, and performance status, were not found in structured EHR data and often not in unstructured data either (Kim et al., 2019).

___________________

62 See https://ccc19.org (accessed October 16, 2024).

In summarizing the lessons learned from CCC19, Warner said that “goodwill was critical but can be fleeting” and some type of reward is necessary to sustain engagement. Studies found that the main factors that drove outcomes were those for which data were often missing or represented only in free text, such as cancer status, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status,63 institutional factors (e.g., differences in surgical outcomes), and COVID-19 vaccination status (Grivas et al., 2021; Hawley et al., 2022; Kuderer et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2022). He said data entries of “unknown” were allowed and missingness was tolerated, but they were taken into account in quality metrics (CCC19, 2020).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Electronic Pathology Implementation Project

Sandy Jones, public health advisor in the cancer surveillance branch at CDC, said that the agency has made significant progress with implementing real-time electronic pathology reporting from laboratories to central cancer registries. However, the lack of structured pathology data presents a persistent challenge and can hamper the identification of reports that should be submitted to registries.

CDC developed the Electronic Mapping, Reporting, and Coding (eMaRC) Plus64 software in 2005 to facilitate the receipt and processing of narrative and synoptic pathology reports by central registries. Jones also described how CDC has used the eMaRC Plus rule-based language model to develop eMaRC Lite,65 a new tool to process narrative pathology reports that reduces the amount of manual review needed. eMaRC Lite determines reportability and auto-codes four required data elements: histology, behavior, primary site, and laterality. More than 30 hospital-based and central cancer registries are currently working with eMaRC Lite. Initial results have shown that a false negative rate of less than 1 percent can be achieved, but, Jones said, “the model will need to be monitored for accuracy and retrained on a regular basis.”

___________________

63 The ECOG Performance Status Scale, developed by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), now known as the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group, was published in 1982. This scale assesses a patient’s level of functioning, with and without restriction, using a variety of factors, including the ability to care for oneself, daily activity, and physical ability (e.g., walking, working). This scale provides a grade from 0 (fully active, no restrictions) to 5 (deceased). See https://ecog-acrin.org/resources/ecog-performance-status (accessed October 23, 2024).

64 See https://www.cdc.gov/national-program-cancer-registries/registry-plus/emarc-plus.html (accessed October 16, 2024).

65 See https://info.cap.org/future-of-cancer-data-summit-insights/downloads/NPCR-ePath-FactSheet.pdf (accessed October 30, 2024).

Jones said that CDC is working to improve the timeliness of cancer reporting. She elaborated on CDC’s partnership with APHL to use its AIMS platform to enable daily reporting to registries by pathology laboratories. The effectiveness of this infrastructure for daily cancer pathology reporting has been demonstrated by nearly 200 laboratories across the United States.66 She added that CDC is developing a national cloud-based platform to enable secure, real-time reporting of cancer cases to central registries. The platform will also offer shared tools and services for data processing and analysis. For example, as part of its efforts to improve timely reporting of childhood cancers, CDC launched the NPCR National Oncology rapid Ascertainment Hub (NPCR NOAH).67 This system supports laboratories in reporting pathology data in standard HL7 format. Faster reporting through CDC’s cloud-based platform supports timely assessment of interventions, resource allocation, clinical trial recruitment, and identification of research priorities. Jones also discussed the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA),68 an infrastructure that facilitates the timely exchange of high-quality, standardized data among Quality Health Information Networks (QHINs).69 She emphasized the importance of implementing data standardization for successful data sharing among health care systems “so that systems can automatically populate the appropriate fields in the EHR with data received from other health care systems.”

CodeX Minimal Common Oncology Data Elements

Su Chen, clinical science principal at MITRE and co-chair of the CodeX HL7 Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR), Accelerator discussed leveraging open common data models to advance cancer data interoperability at CodeX.70 Chen explained that CodeX is an HL7 FHIR accelerator, which is a member-driven community focused on advancing clinical specialty data standards, such as minimal Common Oncology Data Elements (mCODE™),

___________________

66 See https://www.cdc.gov/national-program-cancer-registries/data-modernization/advancing-electronic-reporting.html (accessed October 23, 2024).

67 See https://www.cdc.gov/national-program-cancer-registries/about/pediatric-young-adult-cancer.html (accessed October 16, 2024).

68 See https://www.healthit.gov/topic/interoperability/policy/trusted-exchange-framework-and-common-agreement-tefca (accessed October 19, 2024).

69 A Quality Health Information Network (QHIN) is a network that directly connects participating organizations to achieve interoperability. The qualification process includes completing an application, onboarding, and designation. See https://www.healthit.gov/topic/interoperability/policy/trusted-exchange-framework-and-common-agreement-tefca (accessed October 19, 2024).

70 See https://www.hl7.org/codex (accessed October 23, 2024).

to improve patient experience and outcomes in real care settings. A broad range of CodeX use cases are underway, including a pilot focused on cancer registry reporting.

mCODE71 is a core set of common cancer data based on the FHIR common health data exchange standard. Chen explained that mCODE is an open data model that is standardized and affords API capabilities, which can help to implement digital health solutions at scale. She said that standards are only valuable if they are used widely, effectively, and in actual health care settings. Chen noted significant uptake by vendors, with about half of U.S. patient records in vendor systems that use mCODE. A recent study at the Mayo Clinic found that mCODE used in the context of routine patient care increased data capture with minimal to no clinician burden, she continued (Tevaarwerk et al., 2024). In addition, mCODE is now being used for data capture beyond academic hospitals in community cancer clinics.

Now is the time to reshape the cancer data landscape, Chen said, emphasizing that industry, community, and federal agency efforts are aligning, with momentum building from federal agency cancer initiatives, such as the Cancer Moonshot.72

The OneFlorida+ Clinical Data Trust Model for Facilitating Research

Elizabeth Shenkman, professor and chair of the Department of Health Outcomes and Biomedical Informatics at the University of Florida, discussed the OneFlorida+73 Clinical Data Trust74 as a model of a central data repository to facilitate research. OneFlorida+ partners with academic, regional, and statewide health systems across Florida and select partners in Alabama, Arkansas, California, Georgia, and Minnesota and is a PCORnet75 network partner. At the core of OneFlorida+ is the central data trust, which contains EHR data for over 26 million patients spanning 2012 to present, she said.76

Data in the OneFlorida+ Data Trust are derived from EHRs and other sources (see Figure 4) and stored in the formats of the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model77 and PCORnet

___________________

71 See https://hl7.org/fhir/us/mcode (accessed October 23, 2024).

72 See https://www.cancer.gov/research/key-initiatives/moonshot-cancer-initiative (accessed November 1, 2024).

73 See https://onefloridaconsortium.org/about (accessed October 17, 2024).

74 See https://oneflorida.sites.medinfo.ufl.edu/data-2 (accessed October 17, 2024).

75 See https://pcornet.org (accessed November 2, 2024).

76 See https://oneflorida.sites.medinfo.ufl.edu/data-2 (accessed December 4, 2024).

77 See https://www.ohdsi.org/data-standardization (accessed October 17, 2024).

NOTES: ETL = extract, transform, and load; ID = identification; IRB = institutional review board.

SOURCES: Shenkman presentation, July 29, 2024; OneFlorida+ Clinical Research Network, 2024.

Common Data Model,78 Shenkman said. Other elements of the model include privacy-preserving record linkage; data use agreements with partners; and the ability to reidentify patients, with institutional review board (IRB)79 approval, for potential participation in clinical studies.

Shenkman said that very important clinical information, including information on symptoms, adverse events, social determinants of health, and family history, are locked in EHR text notes. To address this, OneFlorida+ developed GatorTron, a large clinical language model for transforming unstructured clinical data for entry into the Data Trust (Yang et al., 2022a) and GatorTronGPT (generative pre-trained transformer), a generative clinical large language model (Peng et al., 2023). Computing capacity and infrastructure were provided through a partnership with NVIDIA.80

Shenkman shared two recent studies that used data in the OneFlorida+ Data Trust. One study used the data to identify individuals at greatest risk for lung cancer to better target screening efforts and monitor the benefits and harms of lung cancer screening (Yang et al., 2022b). The other linked the data to EHR data and Florida SHOTS81 data to identify clinician practices with low human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination rates and evaluate targeted interventions for increasing vaccination.82

Core Clinical Data Elements for Interoperable EHRs in Cancer Surveillance

Peter Stetson, chief health informatics officer at MSK, said, “We want to predict cancer onset, tumor evolution, treatment response, [and] toxicity burden so we can improve care outcomes and value.” However, the ability to leverage AI-based methods in oncology is limited by the ability to obtain high-quality, shareable data.

Stetson described how MSK is approaching this problem using a real-world data model, the Core Clinical Data Elements (CCDE). CCDE is an OMOP-based model drawing on existing models, including NAACCR,

___________________

78 See https://pcornet.org/data/common-data-model (accessed October 17, 2024).

79 IRBs are committees that oversee research involving human subjects to protect human rights and welfare. See https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/cder-offices-and-divisions/institutional-review-boards-irbs-and-protection-human-subjects-clinical-trials (accessed October 17, 2024).

80 See https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/gatortrongpt (accessed October 17, 2024).

81 See https://flshotsusers.com (accessed October 17, 2024).

82 See https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05006833?term=Text (accessed November 26, 2024).

mCODE, and others. He said that MSK is deep phenotyping83 a cohort of patients for whom deep tumor genotyping data are available from the MSK-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (IMPACT®) genotype panel.84 He explained that by using CCDE, MSK has treatment and outcomes data for a cohort of 24,000 deeply phenotyped patients. These data are highly curated and structured, have greater than 95 percent accuracy, and are used by MSK as a reference standard for AI model development and validation of vendor models, Stetson added.

Stetson said that the benefits of the CCDE real-world data model are that it is “relieving the data quality constraint for AI,” offers a “proving ground” for AI model development, and enables data sharing outside of MSK. He added that AI-enabled curation also increases data density more quickly.

Stetson offered his perspective on a road map for moving forward, including creating an automated cancer registry on a national scale; “federated tuning of AI-enabled curation,” establishing academic–industry partnerships to facilitate a “computable phenotype ecosystem,” and enabling “cross-institutional computable journeys” to be able to predict treatment response based on full patient history across time and place of care.

Emerging Directions in Multimodal Health Data Analytics

Peter Clardy, lead of the Clinical Enterprise Team at Google Health, discussed opportunities to integrate AI tools to manage multimodal patient data. Traditional programming systems involve structured inputs, algorithms, and outputs that are highly deterministic, he said. The original AI and machine learning tools involved supervised learning, which Clardy said “would allow datasets that are highly curated with a ground source of truth to perform certain kinds of task-specific data transformations.” Emerging generative language models, such as GPT,85 learn from consuming huge volumes of data and then use an inference process for tasks, such as answering questions or data abstraction.

Clardy described three waves of AI, beginning in the 1980s with limited capabilities and evolving in the 2010s to neural networks that could successfully complete narrow tasks but could be fragile, required expensive training data, were poor at multimodal and sequential data, and could be difficult to interpret (Sharma et al., 2020). Now, in the third wave, the cost of training is lower,

___________________

83 In precision medicine, deep phenotyping is an emerging process that gathers more specific, individualized details on disease manifestations and presentations to better understand potential connections between genetic variations and disease subtypes (Delude, 2015).

84 See https://www.mskcc.org/msk-impact (accessed October 18, 2024).

85 See https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/gpt (accessed October 24, 2024).

and generative AI is more capable of handling multimodal and sequential data, resulting in “rich, expressive outputs,” he said (Howell et al., 2024).

The use of AI in health care was initially focused on what Clardy described as “mid-generation supervised learning tasks,” such as lung or breast cancer detection, pathology predictors, and genomics (Howell et al., 2024). Today, the focus is on multimodal models that can integrate data from a range of sources and formats, learn, and create a range of outputs for different applications (Acosta et al., 2022). As mentioned, a challenge for AI is that “longitudinal comprehensive patient records are multimodal, heterogeneous, and laden with unstructured data,” Clardy said. Other challenges are that health-related questions are “complex and nuanced,” and the more preprocessing of the questions and the data that are done, the more rigid and costly the systems become. And, while tools such as FHIR have increased data interoperability, capturing information from unstructured data is a persistent challenge.

Clardy noted many opportunities to integrate AI tools into health care (e.g., knowledge graphs, optical character recognition tools, and multimodal patient data management), and each will have advantages and disadvantages. Current systems are still relatively deterministic, but he said there is an increasing number of human-in-the-loop hybrid AI tool pilots. Clardy added that although it is still in the proof-of-concept stage, a generative future is emerging, where large models can extract useful individual- and population-level data from large volumes of patient records. A consideration, however, is that clarity regarding how these systems work decreases as the use of generative tools increases, Clardy concluded.

Getting Data into the Record

Several session participants commented on a range of topics related to populating the EHR with the data needed by cancer registries.

Data Elements

Shulman reiterated that essential data elements include cancer recurrence and factors that provide information about why a patient’s clinician has made particular care decisions. The challenge, he said, is balancing “all the things we might want to know with the things that we absolutely have to know.” Chen highlighted the need to consider what other data elements might be needed for clinical actionability. Another area where data elements are lacking across data models is survivorship. She raised a concern that creating “different siloed versions of these data elements” could exacerbate interoperability barriers. Chen called for cross-sector collaboration to establish a cohesive platform that does not add burden, and Yu noted the need for public–private collaboration

to develop a shared vision. Warner said that cancer is many different diseases and suggested there is a need to consider when highly detailed data are needed versus when a subset is sufficient. He added that, whether machine or human, effort is finite, and one cannot have all the elements on every cancer.

Large Language Models