Sickle Cell Disease in Social Security Disability Evaluations: Pain and Treatment Settings (2025)

Chapter: 4 Health Care Delivery in Sickle Cell Disease: Patient Choices, Care Settings, and Health Care Providers

4

Health Care Delivery in Sickle Cell Disease: Patient Choices, Care Settings, and Health Care Providers

Sickle cell disease (SCD) typically manifests with pain and, over time, may lead to progressive deterioration of organ function punctuated by acute exacerbations, both of which can require care in the outpatient setting and inpatient hospitalization. As Chapters 2 and 3 note, acute pain is the most common presenting symptom in individuals with SCD. Early in life, acute pain is most often caused by vaso-occlusion, or a blockage of blood flow, whereas later in life, several disease-related pathologies can cause acute pain (see Chapter 2). Pain crises and other acute SCD-related organ injuries, including acute chest syndrome, stroke, and infection, often require care in the health care setting, but most adults living with SCD manage SCD-related pain at home (Smith et al., 2008). Similarly, pediatric patients and caregivers report they most often manage pain at home (Dampier et al., 2002).

This chapter details the use of various treatment settings, including day hospitals, infusion centers, and emergency department observation units, for people living with SCD, as well as emergency department visits and hospitalizations. The chapter will address item 3a from the Statement of Task:

- When and how often is hospitalization used in the treatment of SCD?

- What factors impact the decision for a patient to present to a hospital for treatment?

- What factors lead to hospital staff’s decision on whether to admit a patient?

- What factors determine the length of hospitalization?

- What factors contribute to hospital readmissions within 30 days of discharge?

- Are any of the factors discussed unique to SCD or used in a different way when making decisions related to hospitalization for individuals with SCD compared to individuals with other impairments?

- How have these considerations changed over the past 10 years?

CARE SETTINGS AND HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS INVOLVED IN CARE

Changes in the Health Care Delivery System

Many changes have occurred within the health care delivery system during the past 15 years that have resulted in decreased emergency department visits and hospitalizations for individuals living with SCD. One key change since 2010 has been the establishment of alternative payment models by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Innovation Center. These models have advanced value-based care while reducing fragmented or duplicative care and preventable emergency department visits (Fowler et al., 2025). As of 2020, 35.4 percent of Medicaid payments, for example, were made through alternative payment models (Health Affairs, 2022). One such model, known as bundled payments, provides one payment for Medicare beneficiaries for 29 defined inpatient clinical “episodes,” such as stroke and sepsis, from the index admission through 90 days after discharge. Although SCD is not included in this bundled payment system, there have been significant “spill-over” activities that include other high-cost patient populations (Fowler et al., 2025).

Another alternative payment model is the Integrated Care for Kids Model, a program for Medicaid beneficiaries that aims to reduce health care costs and improve quality of care for children with complex medical and behavioral needs through early identification of those needs, risk stratification, and service integration. This payment model is designed to break down silos between health care, educational, and out-of-home settings, such as foster care and residential behavioral health, with the goals of improving care coordination and reducing emergency department visits (Jones and Lucienne, 2023).

Concurrent with the establishment of alternative payment models for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries, there has been an increase in types and usage of outpatient settings to reduce emergency department visits and hospital admissions to manage SCD-related complications over the past 10 years.

Alternative Care Settings to Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalizations

With the development of new care settings, the dependence on emergency department and hospitalization management of SCD has decreased. An infusion center or day hospital setting may be appropriate for adults

and children with SCD who only have acute pain management needs, and research has shown them to be effective models of acute care delivery for adults with SCD (Benjamin et al., 2000; Lanzkron et al., 2021). While SCD-specific day hospitals were used initially to provide care, infusion centers have been used increasingly as they are more focused on delivering intravenous treatments for many conditions in addition to SCD, such as inflammatory bowel disease, and delivering chemotherapy for cancer. Staff at SCD-specific day hospitals have extensive expertise in SCD, while staff at infusion centers typically consist of nurses and advanced practice providers such as advanced practice nurses and physician assistants with a broad range of clinical expertise. Both settings operate only during business hours, however, and are only available at limited hospitals with sufficient patient volumes and resources to support these services.

While these care settings are often considered “outpatient” from a billing perspective with a shorter length of stay, the clinical presentation and effect on functioning is physiologically no different from an emergency department visit. However, the day hospital model in a single-site study had an admission rate of 5 percent versus 58 percent from the emergency department (Adewoye et al., 2007). In the ESCAPED trial, time to administer pain medication at an infusion center was 62 minutes compared to 132 minutes in the emergency department, and individuals were 3.8 times more likely to have their pain reassessed within 30 minutes (Lanzkron et al., 2021). In addition, the probability of admission from the infusion center was 9.3 percent compared to 37 percent from the emergency department.

A nine-site study confirmed these results, finding that the probability of inpatient admission was 1.2 percent from the infusion center compared to 39.8 percent from the emergency department (Laperche et al., 2024). Finally, a different single-site study found the mean number of emergency department treat-and-release visits per year per patient fell from 1.4 to 1 after opening an infusion center for SCD care, and the probability of inpatient admission was 2.8 percent versus 52 percent from the emergency department (Bliamptis et al., 2025). Data from a recent multicenter study found that increasing use of infusion centers to care for individuals with SCD could potentially avert over 55,000 hospital stays over 10 years, saving over 6.4 million hours of patient time, $1.9 billion in direct medical costs, and $2 billion in social costs if they were made more widely available. The study authors also estimated that a patient would save approximately $277 a year over 10 years (Skinner et al., 2022).

Another approach to caring for individuals with SCD who only require acute pain management is to move them to an emergency department-based observation unit. Emergency department-based observation units are designed to care for patients who are expected to require inpatient-level of care for less than 24 hours and are staffed by emergency department physicians,

advanced practice providers, or both who follow clinical care protocols for patients with specific conditions who meet eligibility criteria. One study found this approach reduced the hospital admission rate for adults with SCD from 33 percent to 20 percent and hospital return rates from 67 percent to 41 percent at 30 days (Lyon et al., 2020). Another study also found the hospital admission rate for adults with SCD was lower from the emergency department-based observation unit (36 percent) than from the emergency department (53 percent) (Cline et al., 2018). Emergency department-based observation units are only available at a limited number of hospitals with sufficient patient volumes and resources to support these services.

Emergency Department Visits for Sickle Cell Disease

Some individuals with SCD have frequent, severe complications that require evaluation and treatment in the emergency department setting. Data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey showed individuals living with SCD made approximately 222,000 visits annually, reflecting an estimated 13 percent increase from 1999 to 2020, with severe pain crises accounting for two-thirds of these visits. This study also found that children (aged 0-19 years) with SCD were more likely to be admitted to the hospital than adults, at 35 percent versus 26 percent, respectively (Attell et al., 2024).

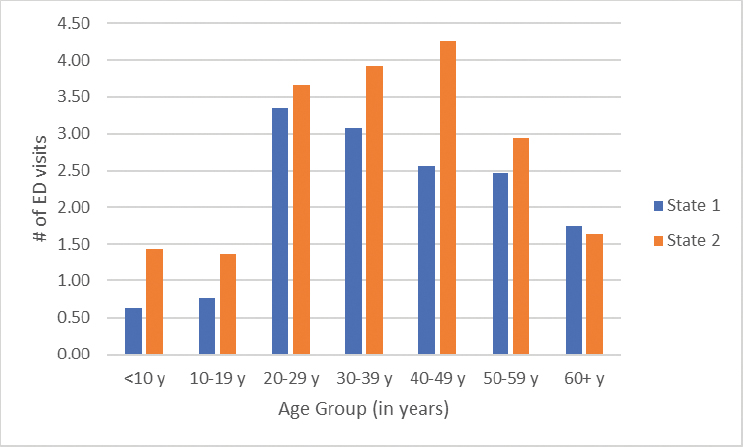

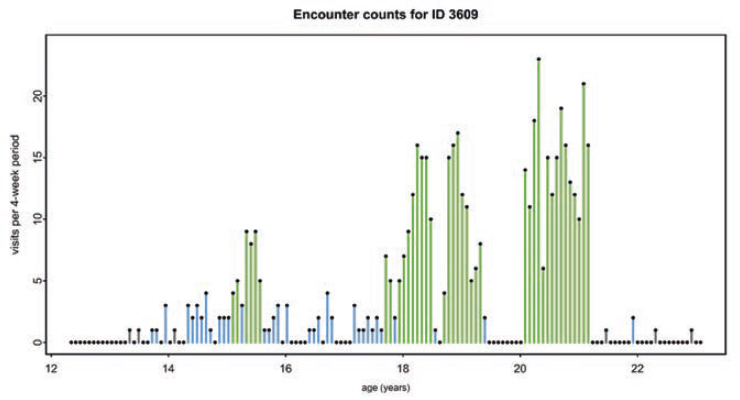

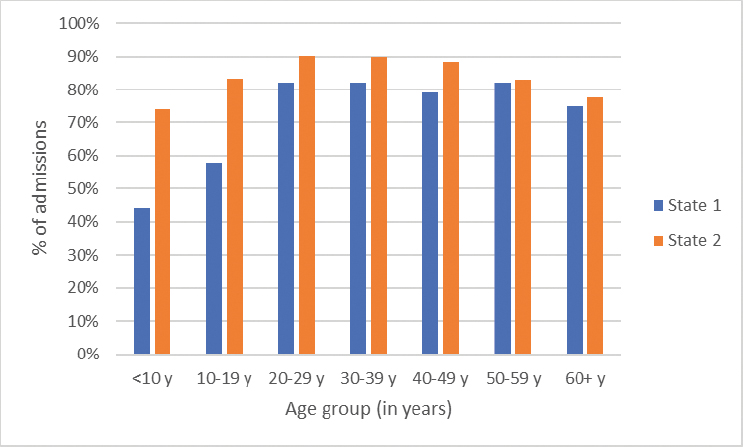

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), most people living with SCD visit the emergency department at some point in their lives (CDC, 2023). CDC established the Sickle Cell Data Collection program in 2015 to characterize the epidemiology of SCD in California and Georgia, which together are home to approximately 15,000 people with SCD (Snyder et al., 2022). Examining these data has provided critical insights into the frequency and nature of emergency department visits and hospital admissions, the duration of stays, and hospital readmissions. In 2019, the number of treat-and-release emergency department visits increased two- to three-fold from childhood to adulthood (Figure 4-1). Emergency department use can vary over time for an individual living with SCD, with multiple visits one year and few to no emergency department visits in subsequent years (Figure 4-2). Furthermore, over 75 percent of hospitalizations for people 20 years and older living with SCD began in the emergency department (Figure 4-3).

The types of health care providers in the emergency department setting vary between the pediatric and adult setting, as well as the academic versus community hospital setting. Pediatric emergency departments are found in academic centers. They are staffed primarily by health care providers who completed residencies in pediatrics or family medicine, and most of whom are board-certified in pediatric emergency medicine. Most pediatric residencies

SOURCE: Sickle Cell Data Collection, unpublished, presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024, by Mary Hulihan.

NOTE: Around the time this individual turned 21, and continuing to almost age 24, the individual’s emergency department use was infrequent or not at all.

SOURCES: Sickle Cell Data Collection, unpublished, presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024, by Mary Hulihan. Paulukonis et al., 2018, p. 159. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

SOURCE: Sickle Cell Data Collection, unpublished, presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024, by Mary Hulihan.

include rotations in hematology/oncology and emergency medicine, providing training in caring for children with SCD in emergency department and inpatient settings. Adult academic emergency departments are staffed by a range of health care providers including board-certified emergency medicine physicians and advanced practice providers, neither of whom routinely receive dedicated training on SCD from expert SCD health care providers across care settings. Health care providers in community hospital emergency departments may include physicians and advanced practice providers with focused expertise and training in emergency medicine, as well as health care providers trained in family medicine and internal medicine and who received on-the-job training. Again, providers in this setting often do not receive dedicated training on SCD from expert SCD health care providers across care settings.

Hospitalizations for Sickle Cell Disease

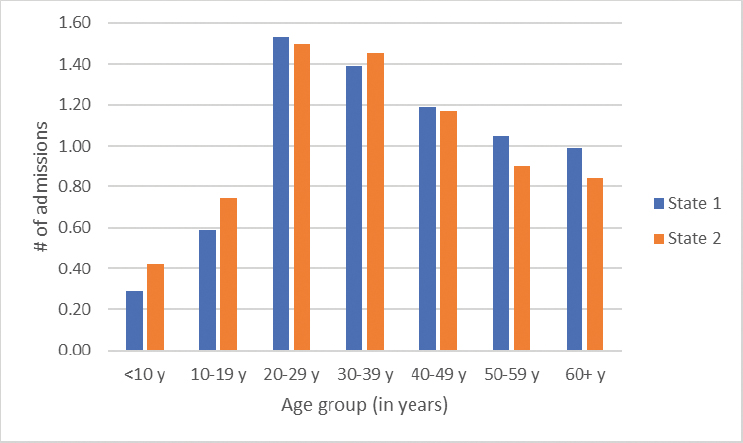

According to 2019 data from the CDC’s Sickle Cell Data Collection program, the average number of hospital admissions for people living with SCD varied by age group (Figure 4-4), with the 20 to 29 and 30 to 39 age groups representing peak ages for hospitalization. The rate of hospitalization varies by age, from approximately 0.2 to 0.7 times per year for children to a maximum average of as much as 1.5 times per year for the 20 to 29 age group.

SOURCE: Sickle Cell Data Collection, unpublished, presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024, by Mary Hulihan.

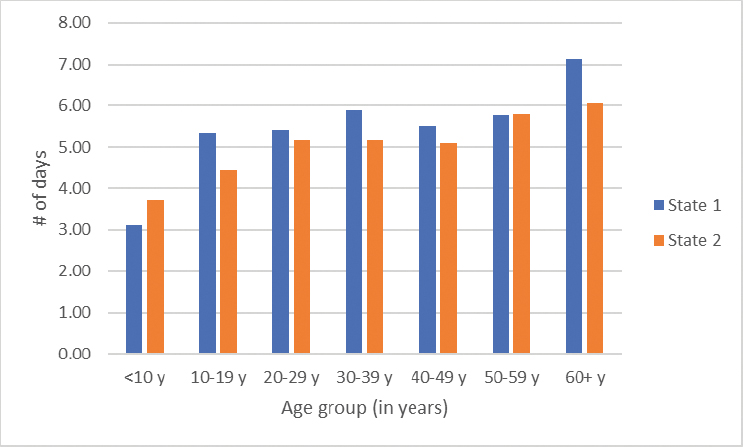

The average length of stay also varies by age (Figure 4-5). Children under 10, for example, stay an average of three to almost four days per hospitalization, with the average length of stay increasing as individuals get older. However, these average numbers of annual admissions and length of stay must be interpreted knowing that a significant proportion may not have any acute care utilization. A retrospective study of eight states found that 29 percent of people in the study population had no sickle cell-related emergency department visits or hospitalizations over a 2-year period (Brousseau et al., 2010).

“I experience one to two crises annually. Last year I experienced a change in the type and intensity of pain. My crisis precipitated acutely in minutes. I cannot manage with oral medication at home. I have to go to the [emergency department] for emergency treatment. My hospitalizations used to be 3 days tops. Now I’m in the hospital 5 to 6 days. . . . I have also noticed that full recovery after discharge from the hospital takes several weeks.”

—Adult living with SCD1

Similarly, inpatient data for SCD published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project estimated

___________________

1 Excerpt from Call for Perspectives Response.

SOURCE: Sickle Cell Data Collection, unpublished, presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024, by Mary Hulihan.

that inpatient stays for children and adults with SCD cost more than $800 million in 2016, with those aged 18 to 34 years incurring more than 50 percent of those costs (Fingar et al., 2019). Data from the National Inpatient Sample revealed that length of stay for adults with SCD decreased by half a day from 5.6 days in 2010 to 5.1 days in 2019 (Deenadayalan et al., 2023).

The types of health care providers who treat SCD in the hospital setting vary by patient age. Children with SCD are treated most commonly by a pediatrician-led team, and care is directed by pediatric subspecialists, such as pediatric hematologists-oncologists, in the tertiary or quaternary care settings. After transition to adult care, most inpatients with SCD are managed by hospitalists or primary care providers without dedicated formal training in SCD across care settings. In addition, there may not be any guidance provided by a health care provider with SCD expertise during the inpatient admission because of a workforce shortage, as many older hematologists are retiring and fewer physicians are entering the field (NASEM, 2020).

Table 4-1 summarizes the different types of acute care settings for children and adults living with SCD, the interventions they provide, the expertise of the care providers, and the options to escalate treatment to the next level of care.

TABLE 4-1 Acute SCD Care Settings

| Setting (Typical Hours of Accessibility) | Interventions | Role & Expertise of Person(s) Implementing Care | Options for Escalation of Care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults and Children | |||

| Home (24 hours/day, 7 days/week) | Oral hydration | Patient (child or adolescent) | Infusion center or day hospital |

| Oral pain medications, including opioids | Parent or caregiver | ED | |

| Sickle Cell Clinic (8 a.m. - 5 p.m., Monday - Friday) | IV fluids | +/− Home health aid | Day hospital |

| +/− Intramuscular or subcutaneous opioids | Registered nurse, nurse practitioner +/− health care provider with pediatric hematology/oncology, adult hematology, or SCD expertise | ED | |

| +/− IV opioids | Health care provider with pediatric hematology/oncology, adult hematology, or SCD expertise | ||

| Infusion Center (8 a.m. - 5 p.m., Monday - Friday) | IV fluids | Registered nurse, nurse practitioner | ED |

| IV pain medications, including ketorolac and opioids | +/− Health care provider with pediatric hematology/oncology, adult hematology, or SCD expertise | ||

| +/− Ketamine (oral or IV) | |||

| +/− Patient-controlled analgesia | |||

| +/− Simple blood transfusion | |||

| +/− Apheresis | |||

| Setting (Typical Hours of Accessibility) | Interventions | Role & Expertise of Person(s) Implementing Care | Options for Escalation of Care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day Hospital (8 a.m. - 5 p.m., Monday - Friday) | IV fluids | Registered nurse, nurse practitioner | ED |

| IV medications, including ketorolac and opioids | Health care provider with pediatric hematology/oncology, adult hematology, or SCD expertise | ||

| +/− Ketamine (oral or IV) | |||

| +/− Simple blood transfusion | |||

| Patient-controlled analgesia | |||

| Children | |||

| Pediatric* ED (24 hours/day, 7 days/week) | IV fluids | Pediatric registered nurse | Inpatient unit |

| *Note that many children present to adult EDs | IV opioids | Pediatric emergency medicine physician | ICU |

| Intranasal fentanyl | |||

| +/− Ketamine (oral or IV) | |||

| +/− Patient-controlled analgesia (rare) | |||

| Hospital Pediatric Inpatient Unit (24 hours/day, 7 days/week) | IV fluids | Pediatric hematology/oncology physician* | Tertiary and quaternary pediatric hospital |

| IV opioids | Pediatric health care provider | ICU | |

| Patient-controlled analgesia | * Non-urban pediatric hospitals may only have pediatric hospitalists | ||

| Simple blood transfusion | |||

| +/− Ketamine (oral; IV rare) | |||

| +/− Apheresis | |||

| Setting (Typical Hours of Accessibility) | Interventions | Role & Expertise of Person(s) Implementing Care | Options for Escalation of Care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Pediatric ICU (24 hours/day, 7 days/week) | IV fluids | Pediatric critical care registered nurse | Tertiary and quaternary pediatric hospital |

| IV opioids | Pediatric critical care physician | ||

| Patient-controlled analgesia | Pediatric critical care provider | ||

| Simple blood transfusion | |||

| Ketamine (oral or IV) | |||

| +/− Apheresis | |||

| +/− Lidocaine infusion |

NOTES: “Health care provider” includes both physicians and advanced practice providers; +/− = variability by health system; ED = emergency department; ICU = intensive care unit; IV = intravenous.

Use of Individualized Care Plans

Individualized care plans are a guideline-recommended tool used to help mitigate the negative effects of care variability for individuals living with SCD when needing more intensive therapies for a pain crisis or SCD-related complication (Brandow et al., 2020; NHLBI, 2014). Many studies that examined the effectiveness of individualized care plans were conducted only in the emergency department setting (Powell et al., 2018; Schefft et al., 2018; Siewny et al., 2024; Tanabe et al., 2017). These studies, in addition to others, demonstrated more timely pain management, improved patient experience in the emergency department, and possibly decreased risk of hospital admission (Balsamo et al., 2019). Other limited data show that for children with SCD, individualized care plans improve home pain management and decrease the risk of an emergency department visit and hospitalization (Crosby et al., 2014). During hospital admissions, individualized care plans may support decreasing length of stay and total amounts of opioids for individuals with SCD who are more frequently in the hospital (Liles et al., 2014; Welch-Coltrane et al., 2021).

DECIDING TO ESCALATE CARE

Individuals with SCD must often decide on when and where to seek additional care once they have exhausted pain management strategies in their home environment, start to experience other SCD-related complications, or both. One study identified four prominent themes that influenced delays in care seeking in young adults with SCD despite experiencing ongoing pain: (1) trying to treat pain at home (77 percent), (2) avoiding the emergency department because of past treatment experiences (55.7 percent), (3) the desire to avoid admission to the hospital (47.8 percent), and (4) the importance of time in the lives of the young adults with SCD as a factor in avoiding admission (54.1 percent) (Jenerette et al., 2014).

If an individual with SCD already has established care with a comprehensive SCD center, they may have access to acute care visits at a clinic, an infusion center, a day hospital, or a combination (Table 4-1). It is also important to acknowledge how the SCD pain episode evolves and the individual’s perception of the pain. A slow, nagging onset that builds over time may lead to home pain management. However, a rapid escalation where pain jumps suddenly from manageable levels (e.g., 7 or 8 on a scale of 10) to unbearable (10+) within an hour or so may lead to earlier care seeking. In these cases, seeking hospital care early is crucial. If a patient delays departing for the hospital while at a 7 or 8 pain level, the pain will likely become unmanageable by the time they arrive, highlighting the need for advocacy and timely care. If those care settings are accessible, other considerations then include availability, anticipated duration of the pain crisis, and likelihood of other complications:

- Is it a Sunday evening and only the emergency department is available, but the infusion center will open at 8:00 on Monday morning? If so, the individual may decide to cope with the pain crisis another 12 hours at home and go to the infusion center in the morning.

- Is it a Friday morning, but the pain crisis is severe and expected to last through the weekend? This individual may go directly to the emergency department since they anticipate needing a hospital admission for management of their pain crisis.

- Does the individual have a fever and cough like the last time acute chest syndrome was diagnosed? If so, they may have to go to a hospital where they know they can receive expert SCD care, which is not available in all, or even most, emergency department or hospital settings.

These are only some of the questions and considerations that may affect where an individual with SCD seeks care during an escalating crisis. Box 4-1 illustrates the type of decision-making process in which an individual with SCD or their caregiver might engage.

BOX 4-1

Decision Tree: Managing Sickle Cell Pain at Home to Hospitalization

-

Pain Management at Home

Start: Experiencing sickle cell pain

Home Interventions:- Hydration by increasing fluid intake

- Over-the-counter pain relievers, such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen

- Prescription pain medication, if available

- Warm compresses and rest

- Breathing exercises and relaxation techniques

-

Pain Reassessment (Time variable)

Is the pain improving? Do negative aspects of care seeking outweigh the potential positives?- Yes: Continue home management and monitor symptoms

- No: Move to next step

- Fever (≥101°F) → Risk of infection

- Shortness of breath → Possible acute chest syndrome

- Swelling in arms/legs → Possible blood clot

- Persistent vomiting → Risk of dehydration

- Mental confusion or severe fatigue → Possible oxygen deprivation

Is the pain improving? Do negative aspects of care seeking outweigh the potential positives? Are other symptoms and signs absent?- Yes: Continue home management and monitor symptoms

- No: Move to next step

-

Seeking Outpatient or Emergency Care

Is a primary care or sickle cell specialist available?- Yes: Contact for urgent appointment or advice on next steps

- No: Proceed to Emergency Department/Urgent Care/Day Hospital/Infusion Center

For many individuals living with SCD, going to the emergency department is a last resort, largely because of their prior experiences, including encountering a lack of knowledge about SCD and its symptoms among emergency department professionals (Abdallah et al., 2020; Lapite et al., 2023). One study, for example, found that about 50 percent of people living with SCD who had a pain crisis in the past six months that was sufficiently severe to interfere with their usual daily activities had not visited the emergency department over the course of the past 12 months (Linton et al., 2020), preferring to stay home and manage their pain as best as possible. Over 80 percent of those who go to the emergency department are walk-ins, as opposed to coming in via ambulance, with pain being the most common complaint (Attell et al., 2024). Most 911 calls for patients with SCD are dispatched as lower-urgency basic life support runs. This designation often results in delay of treatment, and cases are handled by emergency medical technicians with a basic license who are unable to administer needed intravenous medications. This contributes to individuals with SCD presenting independently to the emergency department rather than arriving by ambulance.

“It has to be worth it to go and seek medical attention. We don’t want to be there because we already know what we will face, unfortunately, in that space. This can last for days or weeks if we are admitted, and we are already thinking about what we will miss, what can I not do. Sometimes we are under pressure. We have to think about work, and if I can maybe leave here under a pain scale of 4, I can have a full paycheck.”

—Sharee T., adult living with SCD2

Studies show that individuals often experience stigma and biased care from health care staff, manifesting as questioning of their own lived experience and SCD expertise while perpetuating “drug-seeking” stereotypes (Wu et al., 2024). A review of 27 studies of stigma in SCD found four domains: (1) social consequences of stigma, (2) the effect of stigma on psychological well-being, (3) the effect of stigma on physiological well-being, and (4) the impact of stigma on patient-provider relationships and care-seeking behaviors. All four domains are associated with negative consequences (Bulgin et al., 2018).

“There are times I feel my care management is so poor in the hospital that I actually should just let them discharge me because I am uncertain that my health is in the best hands. There have been times people were so hostile to me in the hospital I was afraid to sleep because I didn’t know if they would do something to me when I was in bed.”

—Christelle S., adult living with SCD3

___________________

2 Presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024.

3 Presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024.

HEALTH CARE PROVIDER DECISIONS TO ADMIT TO THE HOSPITAL

In most cases, health care providers in the emergency department decide on the disposition of a patient within six to eight hours of an initial presentation. This can include discharge from the emergency department to home or to an outpatient facility, such as an infusion center; admission to an emergency department-based observation unit for less than 24 hours; or admission to the hospital. Factors informing this decision include the clinical stability and acute care needs of the patient, whether they have access to an infusion center or other SCD-specific outpatient care facilities, and the expected duration of needed acute care services. If the individual’s vital signs are persistently abnormal, it is likely they need further intervention and will be admitted to the hospital. Similarly, if there is a high suspicion or confirmed presence of acute complications, such as acute chest syndrome, the patient will be admitted. Social drivers of health and access to care are also considered in the decision to admit an individual to the hospital. A patient with SCD who does not have access to pain medications at home or the ability to see an SCD expert in 24 to 48 hours may be prioritized for a hospital admission.

FACTORS UNIQUE TO SICKLE CELL DISEASE IN MAKING DECISIONS RELATED TO HOSPITALIZATION

Many factors affecting decisions related to hospitalization that the preceding sections addressed are unique to SCD, with the medical and psychosocial complexity intersecting for many individuals with SCD. In addition, this complexity tends to increase across an individual’s lifespan as SCD causes progressive multi-organ damage. Vaso-occlusive crises, for example, are cyclical and often unpreventable even when predictable, such as with weather changes. They are associated with severe and life-threatening complications and are challenging to manage in the home setting. Access to comprehensive SCD care and outpatient care coordination supports can enable individuals with SCD to stay out of the emergency department and hospital, but many individuals living with SCD in the United States lack access to this level of comprehensive SCD care (Kanter et al., 2020; Phillips et al., 2022; Schlenz et al., 2016). The unpredictable nature of vaso-occlusive crises combined with the risks of morbidity and mortality lead to a vicious, repetitive cycle of emergency department visits and admissions for some individuals. The mortality risk associated with re-presenting to the hospital after a recent admission often drives the decision to readmit a patient (Ballas and Lusardi, 2005).

Exchange transfusion, or apheresis, is required at times for acute complications of SCD and vaso-occlusive complications such as severe acute chest syndrome and stroke. This highly specialized procedure is not available at

all hospitals. When needed and not available, patients must often transfer to another hospital. Delays in care (Mueller et al., 2021; Shannon et al., 2021) often occur when interhospital transfer is needed because of hospital overcrowding (Hoot et al., 2021) and lack of bed availability, sometimes resulting in increased length of stay, increased rates of complications, and increased complexity of the discharge process.

FACTORS AFFECTING LENGTH OF HOSPITALIZATION

Many of the factors influencing a patient’s length of stay in the hospital mirror the factors that determine the initial decision to admit: the clinical stability of the patient, their ability to access or follow-up with a sickle cell expert and access an infusion center or day hospital for continued pain management and opioid tapering, as well as whether the health care provider believes the patient’s report of pain or other symptoms. Ultimately, the duration an individual with SCD should stay in the hospital depends on whether it is safe for them to go home. Are labs stable or improving? Are their vital signs reassuring? Are there signs of blood cells breaking down or kidney injury? Are there signs of infection? These are questions the health care providers caring for patients with SCD in the hospital ask when deciding whether a patient still warrants hospitalization.

Increased length of stay is often associated with increasing patient complexity from medical factors, psychosocial factors, or both (Feeney et al., 2022, 2023). It is also important to consider an individual’s other chronic conditions. For example, it becomes more common across the lifespan for individuals with SCD to have heart failure, lung disease, or kidney disease as they age or to have a stroke or neurocognitive deficits, making it important to make sure the individual is stable prior to discharge. Psychosocial considerations may include issues related to housing instability, lack of insurance and access to medications, and difficulties with the self-management skills required to effectively manage a chronic condition. Comorbid depression has also been associated with higher rates of hospitalizations, longer length of stay, greater illness severity, and higher charges during hospitalization (Jonassaint et al., 2016; Kidwell et al., 2021; Onyeaka et al., 2019). These factors may lead to more complex acute care needs, as well as difficulties navigating the discharge process and transition out of the hospital.

Length of stay may increase when attempting to avoid hospital readmissions, a priority for patients and health systems alike. One study found that for some young adults with childhood-onset chronic conditions, including SCD, there may be longer lengths of stay in pediatric hospitals versus adult hospitals, but the rates of readmission were lower in the pediatric hospitals (Lutmer et al., 2025). The investigators hypothesized that the increased length of stay may be partially attributed to pediatric hospitals investing

in additional resources such as care coordination to decrease readmission rates. Addressing transitional care needs from the hospital to home or hospital to other discharge locations, such as a skilled nursing facility, also contributes to increased length of stay.

There is considerable variability in the training and expertise of the health care providers caring for children and adults with SCD who are hospitalized. It is more common for children with SCD than for adults to receive care primarily from their SCD care team when admitted. Adults with SCD, in contrast, more often receive care from hospital medicine providers, with or without consultation from an SCD expert or hematologist. In some cases, pediatric hematologists may extend care to adults with SCD because of the shortage of adult hematologists who treat the disease. Several retrospective cohort studies suggest that while adults with childhood-onset conditions, including SCD, often have shorter lengths of stay when cared for in adult hospitals compared to pediatric hospitals, some populations may have increased morbidity and risk of readmission (Jan et al., 2013a; Jan et al., 2013b; Okumura et al., 2006). Taken together, using length of stay as a metric of disease severity is challenging given the patient-, provider-, and system-level issues that affect this quality-of-care indicator.

NAVIGATING CARE TRANSITIONS AND THE DISCHARGE PROCESS

When the decision is made to discharge an individual with SCD from the hospital, it is important to determine not only whether they are clinically stable enough for discharge but also what additional support the person needs for a safe discharge. Ruchi Doshi, a dually trained internal medicine and pediatric hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at Duke University, emphasized to the committee that patient supports during the transition from hospital to an outpatient care environment, such as the home, include care coordination, access to medications, and the ability to carry out activities of daily living.4 Care coordination support encompasses ensuring the individual can make outpatient appointments with both primary care providers and specialists and has transportation to get to scheduled appointments. Access to medication means the health care team ensures the patient can afford and acquire medications. Finally, many patients after hospitalization, including those living with SCD, may need additional assistance with activities of daily living, including shopping for groceries, preparing meals, and cleaning their home, until they have fully recovered from their most recent crisis.

___________________

4 Presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024.

FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO HOSPITAL READMISSION

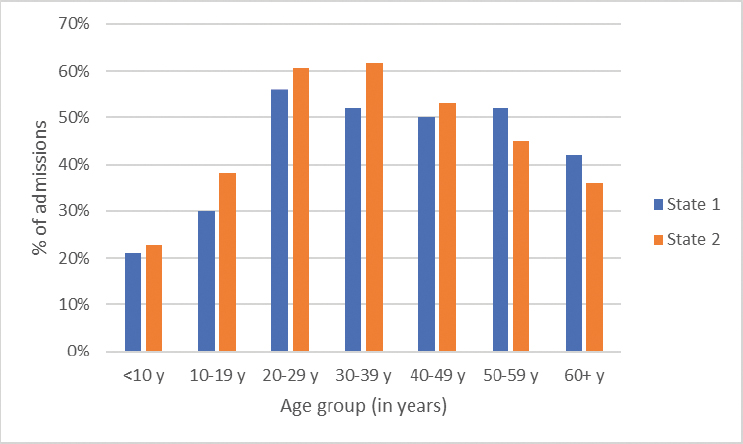

According to 2020 data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, SCD tops the list for 30-day readmissions for adults across all diagnoses (Jiang and Barrett, 2024). Over 50 percent of hospitalizations for 20- to 49-year-olds living with SCD in 2019 were followed by another hospitalization or emergency department visit within 30 days of discharge from the first hospitalization (Figure 4-6).

Readmission can be related to the biology of SCD; a lack of personal resources of the patient; lack of hospital resources, including health care providers with expertise in treating SCD; lack of community resources; or a combination of these. Additional factors related to the biology of SCD and risk of readmissions include sequelae of previous complications or treatment. For instance, strokes are more likely within 30 days of acute chest syndrome (Ohene-Frempong et al., 1998), and hemorrhagic strokes are more common after certain treatments for SCD (Strouse et al., 2006). Life-threatening, delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions can occur after a transfusion given for preventive care or for acute care (Thein et al., 2020) and may resemble a pain crisis. Pain crises, caused by multiple interwoven pathophysiologies, can be stuttering, biphasic, and triphasic and last for weeks depending on the cause. In most cases, medical testing cannot

SOURCE: Sickle Cell Data Collection, unpublished, presented at the “Hospitalization and Sickle Cell Disease – public webinar” on December 20, 2024, by Mary Hulihan.

determine the underlying biology. This means that applying traditional 30-day readmission criteria to the SCD population is challenging because a new, unpredictable, and potentially unpreventable pain crisis may occur within this timeframe.

In addition, reducing the length of inpatient stays may also increase emergency department revisits and readmissions if patients transition too early to outpatient care when they are still experiencing disease exacerbation, including ongoing pain crises. For example, the all-cause 30-day readmission rate for SCD was 46.6 percent when an individual with SCD left the hospital against medical advice (Fingar et al., 2019; Leschke et al., 2012). Individuals with SCD who leave the hospital before they are medically ready may do so because of personal circumstances such as needing to care for a family member or because of the quality of care received during the inpatient stay. Lack of outpatient follow-up with an SCD provider has also been linked to increased readmissions.

Doshi told the committee that one way to prevent readmissions is to facilitate outpatient care. It is important, she said, to coordinate outpatient follow-up, ensure medication availability, and encourage medical adherence. This can be a challenge, though, as most individuals living with SCD still lack access to comprehensive SCD care or other care delivery models that ensure care coordination (Kanter et al., 2020). Community-based organizations can assist individuals living with SCD in many ways, including by providing transportation to and from appointments, assisting with basic needs, and linking them to community resources (NASEM, 2020, Chapter 8, Table 8-1). Addressing social determinants of health, such as transportation to appointments, housing with temperature control, and appropriate home supports, is important, as is avoiding premature discharge. At the same time, there are factors out of the control of the patient or hospital, such as frequent previous hospitalizations; comorbid and concurrent chronic illnesses; the severity of the individual’s disease; and various triggers for vaso-occlusive crises, such as weather, dehydration, and stress (Brodsky et al., 2017).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Most adults and children manage their pain at home. Once they have exhausted pain management strategies in their home environment or start to experience other SCD-related complications, they must decide where and when to seek medical care in other settings. Many people with SCD avoid going to the hospital for a variety of reasons, including past negative treatment experiences and the desire to avoid admission to the hospital. People with SCD often report experiencing stigma and biased care from health care staff.

With the development of new care settings, the dependence on emergency departments and hospitalization management of SCD decreased in select areas of the United States. Infusion centers or day hospitals may be appropriate treatment settings for adults and children with SCD who only have acute pain and require intravenous opioids, and research has shown them to be effective models of acute care delivery associated with decreased emergency department visits and hospitalizations. For these reasons, health care utilization rates as measured by emergency department visits and hospitalizations can underestimate the pain experience, exclude crises that are self-treated at home, and do not account for the effect of pain crises on daily functioning.

Nevertheless, individuals living with SCD have frequent, severe complications that require evaluation and treatment in the emergency department setting. The rates of hospitalization and lengths of stay vary by age, with both generally increasing with increasing age. The types of health care providers in the hospital setting also vary by age. Children with SCD are most commonly treated by a pediatrician-led team, and care is directed by pediatric hematologists-oncologists in the tertiary or quaternary care settings. After transition to adult care, most people with SCD are managed by hospitalists or primary care providers without dedicated formal training in SCD across care settings.

Based on its review of the literature and its expert assessment, the committee reached the following conclusion:

Conclusion 4-1: Sickle cell disease (SCD) treatment in emergency department settings or the number of times a person is hospitalized is too restrictive a measure of disease severity.5

- Growing use of alternative models of care, including home, infusion centers, or day hospitals, has enabled similar levels of care in alternative settings.

- Access to different care settings varies among individuals, depending on distance from types of facilities, insurance coverage, and the availability of specialists in SCD across a broad range of disciplines.

- Many factors other than the severity of an acute pain crisis affect an individual’s decision to seek care and the provider’s decision to recommend admission.

___________________

5 This sentence was changed after release of the report to clarify the limitations of the current measure.

Hospital readmission for people living with SCD is a common occurrence, with over 50 percent of hospitalizations among those 20 to 49 years old being followed by another hospitalization or emergency department visit within 30 days of discharge. Readmission can be related to the biology of SCD, as well as lack of patient, hospital, and community resources. A new, unpredictable, and potentially unpreventable pain crisis or other acute complication of SCD may occur within 30 days of discharge, requiring readmission. In addition, reducing the length of inpatient stays may also increase emergency department revisits and readmissions if patients transition too early to outpatient care when they are still experiencing disease exacerbation, including ongoing pain crises.

Individuals with SCD who leave the hospital before they are medically ready may do so because of personal circumstances such as needing to care for a family member or due to the quality of care received during the inpatient stay. Lack of outpatient follow-up with an SCD provider has also been linked to increased readmissions. Other factors that may contribute to readmissions are out of the control of the individual or hospital, such as frequent previous hospitalizations; comorbid and concurrent chronic illnesses; the severity of the individual’s disease; and various triggers for pain crises, such as weather, dehydration, and stress. All these factors pose challenges for applying traditional 30-day readmission criteria to the SCD population.

Based on its review of the literature and its expert assessment, the committee reached the following conclusion:

Conclusion 4-2: Duration of hospitalization of at least 48 hours and interval to readmission within 30 days is determined by a variety of factors not specific to disease characteristics, including access to care, health care provider and individual preferences, and disease stigma.

REFERENCES

Abdallah, K., A. Buscetta, K. Cooper, J. Byeon, A. Crouch, S. Pink, C. Minniti, and V. L. Bonham. 2020. Emergency department utilization for patients living with sickle cell disease: Psychosocial predictors of health care behaviors. Annals of Emergency Medicine 76(3S):S56–S63.

Adewoye, A. H., V. Nolan, L. McMahon, Q. Ma, and M. H. Steinberg. 2007. Effectiveness of a dedicated day hospital for management of acute sickle cell pain. Haematologica 92(6):854–855.

Attell, B. K., P. M. Barrett, B. S. Pace, M. L. McLemore, B. T. McGee, R. Oshe, A. M. DiGirolamo, L. L. Cohen, and A. B. Snyder. 2024. Characteristics of emergency department visits made by individuals with sickle cell disease in the U.S., 1999-2020. AJPM Focus 3(1):100158.

Ballas, S. K., and M. Lusardi. 2005. Hospital readmission for adult acute sickle cell painful episodes: Frequency, etiology, and prognostic significance. American Journal of Hematology 79(1):17–25.

Balsamo, L., V. Shabanova, J. Carbonella, M. V. Szondy, K. Kalbfeld, D.-A. Thomas, K. Santucci, M. Grossman, and F. Pashankar. 2019. Improving care for sickle cell pain crisis using a multidisciplinary approach. Pediatrics 143(5):e20182218.

Benjamin, L. J., G. I. Swinson, and R. L. Nagel. 2000. Sickle cell anemia day hospital: An approach for the management of uncomplicated painful crises. Blood 95(4):1130–1136.

Bliamptis, J., A. You, J. Groesbeck, S. Sacknoff, S. Byrne, and S. Gopal. 2025. A telemedicine triage model for infusion center–based management of adult sickle cell pain episodes. Blood Advances 9(3):603–605.

Brandow, A. M., C. P. Carroll, S. Creary, R. Edwards-Elliott, J. Glassberg, R. W. Hurley, A. Kutlar, M. Seisa, J. Stinson, J. J. Strouse, F. Yusuf, W. Zempsky, and E. Lang. 2020. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: Management of acute and chronic pain. Blood Advances 4(12):2656–2701.

Brodsky, M. A., M. Rodeghier, M. Sanger, J. Byrd, B. McClain, B. Covert, D. O. Roberts, K. Wilkerson, M. R. DeBaun, and A. A. Kassim. 2017. Risk factors for 30-day readmission in adults with sickle cell disease. The Americam Journal of Medicine 130(5):601.e9–601.e15.

Brousseau, D., P. L. Owens, A. L. Mosso, J. A. Panepinto, and C. A. Steiner. 2010. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 303(13):1288–1294.

Bulgin, D., P. Tanabe, and C. Jenerette. 2018. Stigma of sickle cell disease: A systematic review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 39(8):675–686.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2023. CDC’s Sickle Cell Data Collection program data useful in describing patterns of emergency department visits by Californians with sickle cell disease (SCD). https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/features/kf-sc-data-collection-californians.html (accessed March 20, 2025).

Cline, D. M., S. Silva, C. E. Freiermuth, V. Thornton, and P. Tanabe. 2018. Emergency department (ED), ED observation, day hospital, and hospital admissions for adults with sickle cell disease. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 19(2):311–318.

Crosby, L. E., K. Simmons, P. Kaiser, B. Davis, P. Boyd, T. Eichhorn, T. Mahaney, N. Joffe, D. Morgan, and K. Schibler. 2014. Using quality improvement methods to implement an electronic medical record (EMR) supported individualized home pain management plan for children with sickle cell disease. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management 21(5):210–217.

Dampier, C., E. Ely, D. Brodecki, and P. O’Neal. 2002. Home management of pain in sickle cell disease: A daily diary study in children and adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology 24(8):643–647.

Deenadayalan, V., R. Litvin, J. Vakil, P. Kanemo, H. Shaka, A. Venkataramanan, and M. Zia. 2023. Recent national trends in outcomes and economic disparities among adult sickle cell disease-related admissions. Annals of Hematology 102(10):2659–2669.

Feeney, C., M. Chandler, A. Platt, S. Sun, N. Setji, and D. Y. Ming. 2023. Impact of a hospital service for adults with chronic childhood-onset disease: A propensity weighted analysis. Journal of Hospital Medicine 18(12):1082–1091.

Feeney, C. D., A. Platt, J. Rhodes, Y. Marcantonio, S. Patel-Nguyen, T. White, J. A. Wilson, J. Pendergast, and D. Y. Ming. 2022. Redesigning care of hospitalized young adults with chronic childhood-onset disease. Cureus 14(8):e27898.

Fingar, K. R., P. L. Owens, L. D. Reid, K. B. Mistry, and M. L. Barrett. 2019. Characteristics of inpatient hospital stays involving sickle cell disease, 2000–2016. HCUP Statistical Brief #251 (September). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb251-Sickle-Cell-Disease-Stays-2016.pdf.AHRQ (accessed April 30, 2025).

Fowler, E., P. Rawal, and R. Calloway. 2025. The spillover effect of the CMS Innovation Center. NEJM Catalyst 6(1).

Health Affairs. 2022. Value-based payment as a tool to address excess US health spending. Health Affairs Research Brief (December 1). https://doi.org/10.1377/hpb20221014.526546.

Hoot, N. R., R. C. Banuelos, Y. Chathampally, D. J. Robinson, B. W. Voronin, and K. A. Chambers. 2021. Does crowding influence emergency department treatment time and disposition? JACEP Open 2(1):e12324.

Jan, S., G. Slap, D. Dai, and D. M. Rubin. 2013a. Variation in surgical outcomes for adolescents and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Pediatrics 131 (Supplement_1):S81–S89.

Jan, S., G. Slap, K. Smith-Whitley, D. Dai, R. Keren, and D. M. Rubin. 2013b. Association of hospital and provider types on sickle cell disease outcomes. Pediatrics 132(5):854–861.

Jenerette, C. M., C. A. Brewer, and K. I. Ataga. 2014. Care seeking for pain in young adults with sickle cell disease. Pain Management Nursing 15(1):324–330.

Jiang, H. J., and M. L. Barrett. 2024. Clinical conditions with frequent, costly hospital readmissions by payer, 2020. Statistical Brief #307 (April). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/SB307-508.pdf (accessed April 30, 2025).

Jonassaint, C. R., V. L. Jones, S. Leong, and G. M. Frierson. 2016. A systematic review of the association between depression and health care utilization in children and adults with sickle cell disease. British Journal of Haematology 174(1):136–147.

Jones, E. B., and T. M. Lucienne. 2023. The integrated care for kids model: Addressing fragmented care for pediatric Medicaid enrollees in seven communities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 34(1):503–509.

Kanter, J., W. R. Smith, P. C. Desai, M. Treadwell, B. Andemariam, J. Little, D. Nugent, S. Claster, D. G. Manwani, J. Baker, J. J. Strouse, I. Osunkwo, R. W. Stewart, A. King, L. M. Shook, J. D. Roberts, and S. Lanzkron. 2020. Building access to care in adult sickle cell disease: Defining models of care, essential components, and economic aspects. Blood Advances 4(16):3804–3813.

Kidwell, K., C. Albo, M. Pope, L. Bowman, H. Xu, L. Wells, N. Barrett, N. Patel, A. Allison, and A. Kutlar. 2021. Characteristics of sickle cell patients with frequent emergency department visits and hospitalizations. PLOS One 16(2):e0247324.

Lanzkron, S., J. Little, H. Wang, J. J. Field, J. R. Shows, C. Haywood, Jr., M. Saheed, M. Proudford, D. Robertson, A. Kincaid, L. Burgess, C. Green, R. Seufert, J. Brooks, A. Piehet, B. Griffin, N. Arnold, S. Frymark, M. Wallace, N. Abu Al Hamayel, C. Y. Huang, J. B. Segal, and R. Varadhan. 2021. Treatment of acute pain in adults with sickle cell disease in an infusion center versus the emergency department: A multicenter prospective cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine 174(9):1207–1213.

Laperche, J. C., A. Apudhyay, M. Eakin, A. A. Boucher, L. M. Decastro, S. H. Guarino, R. Kribs, W. R. Smith, V. Morgan-Smith, A. R. O’Brien, A. Lauriello, J. A. Little, C. Sylvestre, and S. Lanzkron. 2024. Comparing emergency department and infusion clinic outcomes among individuals with sickle cell disease seeking care for vaso-occlusive crises. Blood 144(Supplement 1):5062.

Lapite, A., I. Lavina, S. Goel, J. Umana, and A. M. Ellison. 2023. A qualitative systematic review of pediatric patient and caregiver perspectives on pain management for vaso-occlusive episodes in the emergency department. Pediatric Emergency Care 39(3):162–166.

Leschke, J., J. A. Panepinto, M. Nimmer, R. G. Hoffmann, K. Yan, and D. C. Brousseau. 2012. Outpatient follow-up and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease patients. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 58(3):406–409.

Liles, E. A., J. Kirsch, M. Gilchrist, and M. Adem. 2014. Hospitalist management of vaso-occlusive pain crisis in patients with sickle cell disease using a pathway of care. Hospital Practice (1995) 42(2):70–76.

Linton, E. A., D. A. Goodin, J. S. Hankins, J. Kanter, L. Preiss, J. Simon, K. Souffront, P. Tanabe, R. Gibson, L. L. Hsu, A. King, L. D. Richardson, and J. A. Glassberg. 2020. A survey-based needs assessment of barriers to optimal sickle cell disease care in the emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine 76(3):S64–S72.

Lutmer, J., E. Bucholz, K. A. Auger, M. Hall, J. Mitchell Harris, 2nd, A. Jenkins, R. Morse, M. I. Neuman, A. Peltz, H. K. Simon, and R. J. Teufel, 2nd. 2025. Association between hospital type and length of stay and readmissions for young adults with complex chronic diseases. Journal of Hospital Medicine 20(4):335–343.

Lyon, M., L. Sturgis, R. Lottenberg, M. E. Gibson, J. Eck, A. Kutlar, and R. W. Gibson. 2020. Outcomes of an emergency department observation unit-based pathway for the treatment of uncomplicated vaso-occlusive events in sickle cell disease. Annals of Emergency Medicine 76(3S):S12–S20.

Mueller, S. K., E. Shannon, A. Dalal, J. L. Schnipper, and P. Dykes. 2021. Patient and physician experience with interhospital transfer: A qualitative study. Journal of Patient Safety 17(8):e752–e757.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2020. Addressing sickle cell disease: A strategic plan and blueprint for action. Edited by M. McCormick, H. A. Osei-Anto, and R. M. Martinez. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NHLBI (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute). 2014. Evidence-based management of sickle cell disease. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Ohene-Frempong, K., S. J. Weiner, L. A. Sleeper, S. T. Miller, S. Embury, J. W. Moohr, D. L. Wethers, C. H. Pegelow, F. M. Gill, and the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. 1998. Cerebrovascular accidents in sickle cell disease: Rates and risk factors. Blood 91(1):288–294.

Okumura, M. J., A. D. Campbell, S. Z. Nasr, and M. M. Davis. 2006. Inpatient health care use among adult survivors of chronic childhood illnesses in the United States. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 160(10):1054–1060.

Onyeaka, H. K., U. Queeneth, W. Rashid, N. Ahmad, S. Kuduva Rajan, P. R. Jaladi, and R. S. Patel. 2019. Impact of depression in sickle cell disease hospitalization-related outcomes: An analysis of the National Inpatient Sample (NIS). Medicina 55(7):385.

Paulukonis, S. T., E. Roberts, R. Brathwaite, T. Wun, and M. M. Hulihan. 2018. Episodes of high emergency department utilization among a cohort of persons living with sickle cell disease. Blood 132(Supplement 1):159.

Phillips, S., Y. Chen, R. Masese, L. Noisette, K. Jordan, S. Jacobs, L. L. Hsu, C. L. Melvin, M. Treadwell, N. Shah, P. Tanabe, and J. Kanter. 2022. Perspectives of individuals with sickle cell disease on barriers to care. PLOS One 17(3):e0265342.

Powell, R. E., P. B. Lovett, A. Crawford, J. McAna, D. Axelrod, L. Ward, and D. Pulte. 2018. A multidisciplinary approach to impact acute care utilization in sickle cell disease. American Journal of Medical Quality 33(2):127–131.

Schefft, M. R., C. Swaffar, J. Newlin, C. Noda, and I. Sisler. 2018. A novel approach to reducing admissions for children with sickle cell disease in pain crisis through individualization and standardization in the emergency department. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 65(10):e27274.

Schlenz, A. M., A. D. Boan, D. T. Lackland, R. J. Adams, and J. Kanter. 2016. Needs assessment for patients with sickle cell disease in South Carolina, 2012. Public Health Reports 131(1):108–116.

Shannon, E. M., J. Zheng, E. J. Orav, J. L. Schnipper, and S. K. Mueller. 2021. Racial/ethnic disparities in interhospital transfer for conditions with a mortality benefit to transfer among patients with Medicare. JAMA Network Open 4(3):e213474.

Siewny, L., A. King, C. L. Melvin, C. R. Carpenter, J. S. Hankins, J. S. Colla, L. Preiss, L. Luo, L. Cox, M. Treadwell, N. Davila, R. V. Masese, S. McCuskee, S. S. Gollan, and P. Tanabe. 2024. Impact of an individualized pain plan to treat sickle cell disease vaso-occlusive episodes in the emergency department. Blood Advances 8(20):5330–5338.

Skinner, R., A. Breck, and D. Esposito. 2022. An impact evaluation of two modes of care for sickle cell disease crises. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research 11(6):399–409.

Smith, W. R., L. T. Penberthy, V. E. Bovbjerg, D. K. McClish, J. D. Roberts, B. Dahman, I. P. Aisiku, J. L. Levenson, and S. D. Roseff. 2008. Daily assessment of pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Annals of Internal Medicine 148(2):94–101.

Snyder, A. B., S. Lakshmanan, M. M. Hulihan, S. T. Paulukonis, M. Zhou, S. S. Horiuchi, K. Abe, S. N. Pope, and L. A. Schieve. 2022. Surveillance for sickle cell disease – Sickle Cell Data Collection program, two states, 2004-2018. MMWR Surveillance Summaries 71(9):1–18.

Strouse, J. J., M. L. Hulbert, M. R. Debaun, L. C. Jordan, and J. F. Casella. 2006. Primary hemorrhagic stroke in children with sickle cell disease is associated with recent transfusion and use of corticosteroids. Pediatrics 118(5):1916–1924.

Tanabe, P., C. E. Freiermuth, D. M. Cline, and S. Silva. 2017. A prospective emergency department quality improvement project to improve the treatment of vaso-occlusive crisis in sickle cell disease: Lessons learned. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 43(3):116–126.

Thein, S. L., F. Pirenne, R. M. Fasano, A. Habibi, P. Bartolucci, S. Chonat, J. E. Hendrickson, and S. R. Stowell. 2020. Hemolytic transfusion reactions in sickle cell disease: Underappreciated and potentially fatal. Haematologica 105(3):539–544.

Welch-Coltrane, J. L., A. A. Wachnik, M. C. B. Adams, C. R. Avants, H. A. Blumstein, A. K. Brooks, A. M. Farland, J. B. Johnson, M. Pariyadath, E. C. Summers, and R. W. Hurley. 2021. Implementation of individualized pain care plans decreases length of stay and hospital admission rates for high utilizing adults with sickle cell disease. Pain Medicine 22(8):1743–1752.

Wu, J. K., K. McVay, K. M. Mahoney, F. A. Sayani, A. H. Roe, and M. Cebert. 2024. Experiences with healthcare navigation and bias among adult women with sickle cell disease: A qualitative study. Quality of Life Research 33(12):3459–3467.

This page intentionally left blank.