Development, Implementation, and Evaluation of Community-Based Suicide Prevention Grants Programs: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 5 Communicating Program Results

5

Communicating Program Results

After the session focused on program evaluation, the workshop turned to the topic of communicating program results. The session opened with two presentations that established a conceptual basis for broader dialogue in the subsequent moderated panel discussion. Following the panel discussion, the final portion of the session was dedicated to an audience Q&A.

This chapter offers guidance for developing communication strategies that amplify program impact and promote engagement. Effective communication of program results requires intentional strategy, audience engagement, and thoughtful message design. Drawing on insights from behavioral science and suicide prevention practice, this chapter outlines best practices for dissemination—including audience tailoring, data storytelling, visual design, and real-time adaptation—and presents examples of how communication can support impact, build coalitions, and inform public dialogue.

STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION AND DATA STORYTELLING

The foundational presentations in this session explored strategic approaches to communicating program results. Speakers focused on tailoring communications to particular audiences and using data storytelling to convey impact in ways that are clear, compelling, and meaningful to diverse stakeholders.

Best Processes for Strategic Communication of Program Results

Jeff Niederdeppe (Cornell University) began by suggesting it is more appropriate to think in terms of best processes, rather than best practices, as there is no one-size-fits-all approach to effective communication and dissemination. However, he explained, a set of helpful questions and frameworks can guide efforts. Because communication and dissemination activities are often carried out under resource constraints, he stressed the importance of having a clear strategy to maximize impact. Niederdeppe urged participants to bring the same level of thought and planning to communication and dissemination that is typically applied to program implementation and evaluation, emphasizing that some of the same principles and concepts apply across both domains.

Niederdeppe identified a set of key strategic questions that should guide communication and dissemination efforts:

- Why communicate program results?

- How should program results be communicated?

- To whom to say it?

- What to say?

- When to say it?

- Where to say it (via what channels)?

- How to say it (e.g., stories, evidence, figures, statistics)?

- Is there potential for unintended negative consequences?

Put more succinctly, in communication and dissemination, the foundational questions are who, what, when, where, why, how, and with what potential risk. Of these, he noted, why is the most important question—why are we disseminating program results? What is the goal? What is the purpose of these dissemination efforts? He followed up these questions by pointing to the complexity of behavioral, institutional, and policy change processes, which are rarely linear.

To illustrate this complexity, Niederdeppe presented two conceptual models: the COM-B model of planning behavioral interventions and a typical policy process logic model (see Figure 5-1). He emphasized the circular nature of the two models, with various overlapping and intervening factors that may or may not coalesce to create momentum for change. Understanding which pieces must coalesce for change to happen is essential, he said, for determining how and when evidence might inform practice and policy. One pathway is agenda-setting—identifying a topic, program, or policy as important and worthy of attention. Another pathway, Niderdeppe continued, is direct advocacy or persuasion: convincing key audiences that an intervention should be implemented or that an issue should be reframed.

SOURCES: Presented by Jeff Niederdeppe on April 29, 2025. The COM-B model (top) is reprinted from McDonagh and colleagues (2018) under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). The Population Reference Bureau Policy Process: A Theoretical Framework (bottom) is reprinted with permission from Population Reference Bureau (2009).

A third pathway involves mobilizing constituencies, building coalitions, and bringing together stakeholders with shared interests to collaborate on an issue. These strategies are not mutually exclusive, but each requires resources.

Each of these pathways suggests a different set of behaviors and foci, Niederdeppe observed, underscoring the need for a clearly articulated goal and a corresponding theory of change to guide dissemination decisions. If the goal is agenda-setting, Niederdeppe explained, the strategy might involve maximizing community exposure to a topic, because people would see the topic being raised repeatedly as important. If the goal is persuasion, attention must be given to identifying the specific actors to be persuaded, whether they are decision makers, knowledge brokers, or other intermediaries. Reframing an issue toward a more public health community-based approach may require crafting messages that align with shared values and invite audiences to see the issue the same way. Reflecting on the day’s emphasis on a comprehensive public health approach to suicide prevention, Niederdeppe added that while this framing is widely used among researchers and practitioners, it may not resonate as strongly with general policymakers or lay audiences.

If the goal is coalition-building, Niederdeppe continued, it is necessary to determine which organizations and individuals to engage; engagement may need to extend beyond stakeholders focused on suicide prevention for veterans or military personnel, and include those who care about some broader community-based change ideas central to a public health approach, such as workforce development or building connections between people.

Niederdeppe underscored the importance of identifying the intended audience once the “why” is clear, as decades of communication, and dissemination research have demonstrated that understanding the values and beliefs of the audience is central to crafting messages that will resonate. Here, decisions must be made—is the focus on communicating with institutional decision makers? If so, is the emphasis on trying to persuade those who opposed previous policies or programs, or is the purpose to instead mobilize those who already are inclined to support these policies or programs? Or is the aim to target the general public to build pressure from the ground up? Is the purpose to persuade the public that an issue is important, or is the purpose to mobilize those already affected? Niederdeppe followed up these questions by highlighting that scholarly communities are key actors in a broader dissemination and communication strategy.

The next step is to determine what should be said, Niederdeppe noted, cautioning against the common practice of disseminating findings as new evidence is developed, expecting that exposure alone will lead to change. Instead, he advised starting from the end goal, such as promoting a program or changing policy, and then working backward to understand who the

audience is—what are their values and beliefs and how might those drive their support for or opposition to policies or programs (see Figure 5-2). For example, Niederdeppe explained, a decision maker who is trying to decide whether to allocate funding for a suicide prevention program focused on community-level change for veterans might be most persuaded by evidence of improving social connections. For another decision maker, evidence of economic development for veterans, or the overall health impact (suicides prevented, number of people who seek help) might be more persuasive; others might be most concerned about return on investment or political feasibility. Understanding what drives support for or opposition to these policies or programs, he reiterated, is central to determining what messages are likely to resonate with the audience. From there, the process continues by working backward to determine whether new evidence connects directly with the intended audience’s values, or if combining it with well-established existing bodies of scientific knowledge or previous experiential or institutional knowledge about how political and program implementation processes will be more effective.

The timing of dissemination is also critical, Niederdeppe noted. The process of policy and program change and implementation is non-linear,

SOURCE: Presented by Jeff Niederdeppe on April 29, 2025.

and different audiences operate on different time horizons that are important to them. Echoing earlier comments from Yanovitzky, he emphasized that it is fundamental to consider a communication strategy from the very beginning, because it is unlikely that critical audiences will need the information at the very moment evidence or results are published or reported. For example, institutional decision makers will not wait for evidence to come by and then make a decision, they are more likely to seek out relevant findings when a policy window opens or a political opportunity arises. Researchers must be ready, Niederdeppe urged, to engage at those moments. Similarly, public interest may depend on personal experience or news relevance, while practice communities often need guidance long before peer-reviewed results are available. On the other hand, he noted, scholarly audiences may require traditional publication but can influence official guidance and professional norms.

Next, Niederdeppe touched upon dissemination channels. The important questions here, he stated, are where is your audience? Where are they engaging with information? What channels resonate with and reach those audiences? Depending on the answers to these questions, relevant channels may include social media, traditional media, community gatherings, or peer-reviewed literature. He cautioned against jumping to social media platforms and engaging influencers without understanding whether such platforms align with the intended audience’s habits and preferences. What might work for one audience may be ineffective for another audience.

Niederdeppe went on to highlight the value of communication science for dissemination decisions. Research in this field can help determine whether to use storytelling, anecdotes, emotional appeals, data-driven arguments, or direct engagement with opposition. There is a robust body of work that may help inform decision making, but researchers must engage with the work to make use of it effectively.

Finally, Niederdeppe emphasized the importance of considering potential unintentional negative consequences of dissemination efforts. While it is impossible to anticipate all possible outcomes once information enters a complex information ecosystem, some risks are well documented and should be factored into early planning. He suggested keeping in mind the medical principle of “do no harm” and pointing to the Werther effect—the risk of suicide contagion following publicity of a suicide. Other risks include stigmatization, message co-option, or framing that emphasizes individual responsibility rather than a community or public health model. Niederdeppe closed his presentation by cautioning that disseminating results very publicly can run the risk of catalyzing oppositional forces when a subtler or more focused dissemination strategy with decision makers that does not bring in media attention may have a better chance effecting change under the radar and avoid catalyzing oppositional forces.

Data Storytelling: Best Practices for Communicating Impact

Corbin Standley (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention [AFSP]) opened his presentation by framing data storytelling, which combines data, visuals (such graphs, charts, illustrations), and narratives (such as stories about the program and about those impacted), as an approach that helps data come alive and inspire action. He then laid out three steps for effective storytelling:

- Knowing the audience. Audience-specific data communication ensures the message is clear, relevant, and impactful.

- Finding the story. Knowing what the data are saying will help develop a meaningful narrative that is insightful for the audience.

- Visualizing the impact. Displaying data with the right visuals to ensure the story is communicated clearly and interpreted correctly.

In terms of knowing the audience, Standley said, “I always come back to the evaluator’s motto of ‘it depends’—how you’re communicating depends on who your audience is.” The approach to communication should vary depending on who the audience is, what they need, and what response is desired. He suggested considering two guiding questions:

- What do you want the audience to think, feel, or do as a result of encountering the data story, findings, or results?

- What does the audience need to know to get there?

He then outlined how this approach could be applied across four key audiences:

- Researchers and academia.

Desired response: View the findings as credible and as a meaningful contribution to the scholarly discourse.

What they need to know: Is the data valid and reliable, and adding to the body of knowledge? - Funders or donors.

Desired response: Continued or increased support for the programs or interventions.

What they need to know: How has their investment made—or how will it make—a difference? - Policymakers and staffers.

Desired response: Take a legislative or policy action.

What they need to know: How did or will this affect the constituents in my district?

- Community members.

Desired response: View the findings as relevant and trustworthy and be motivated to engage.

What they need to know: How does it affect me, my family, and my community?

To find the story in data, Standley explained, he tends to think about a storytelling structure as a roller coaster, with the storytelling elements taught in middle and high school—rising action, falling action, and conclusion—adapted to a set of five elements and corresponding questions that can help frame findings in a way that resonates with different audiences:

- Context: Why does this matter?

- Characters: Who is impacted by the data and who are the characters in the story?

- Climb: What did the program or intervention do?

- Consequence: What are the findings?

- Conclusion: What does it mean? What should people do as a result? What action are we hoping takes place as a result of these program findings?

To illustrate this approach, Standley shared the development and early evaluation findings from the ASFP program L.E.T.S. Save Lives, an introductory suicide program designed by and for Black and African American communities that was launched in February 2024 (see Figure 5-3). The context was that suicide rates have been increasing in Black and African American communities for several years. Standley highlighted Keon Lewis as one of the key characters of this story. Lewis, a college student at the time, was inspired to act as a result of friends losing loved ones to suicide. He joined a local chapter of AFSP and later approached the national office with the goal to develop a program specifically for Black and African American communities. In response ASFP put together an advisory committee of people with lived experience, scholars, researchers, and experts from Black and African American communities to co-develop the L.E.T.S. Save Lives program, as well as the evaluation—the climb.

Continuing, Standley shared the consequence—or evaluation findings showed early signs of impact, with over 2,000 people reached, 95 percent of participants reporting they feel comfortable supporting a loved one who may be struggling, and a 20 percent increase in participant likelihood to reach out for support for themselves or others. The conclusion, Standley shared, is that a follow-up survey found 60 percent of participants had reached out to someone that they were concerned about within two months after attending the program. “Conversations are happening that weren’t before,” he noted. As part of the next phase, Lewis is partnering with AFSP

SOURCE: Presented by Corbin Standley on April 29, 2025; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

to scale the reach of L.E.T.S. Save Lives through the Omega Psi Phi fraternity and historically Black colleges and universities throughout the country, extending its impact to new communities.

Building on Niederdeppe’s presentation, Standley turned to the question of how to visualize the impact of a data story and effectively communicate it across different platforms and formats. While researchers often default to traditional outputs such as reports and slide shows, he encouraged participants to consider a broader range of formats that can be integrated into communication strategies from the beginning. These might include handouts, posters, data displays, social media graphics, and other materials tailored to the target audience and context.

Standley shared a few examples of real-world data visualizations,1 as well as illustrations of a wide range of visualization options for both

___________________

1 Examples included the Who Was Involved visualization in the “Impact Spotlight” for the 2023 International Survivors of Suicide Loss Day, available at https://www.datocms-assets.com/12810/1732043814-14842_afsp_impact_spotlight_issue3_m1.pdf; and a social media graphic shared on the AFSP Instagram page, viewable at https://www.instagram.com/p/DA59XVct-wA/?img_index=1

As an aside, Standley drew particular attention to the Instagram graphic, which reflects results from an annual Harris Poll commissioned by the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention and the Suicide Prevention Resource Center. According to the 2024 survey, 91 percent of U.S. adults believe suicide can be prevented at least some of the time, a notable increase since the survey began in 2015. Standley framed this shift as evidence of changing public attitudes, echoing earlier comments by Quinlan, and a testament to the collective efforts of those working in suicide prevention at the community and societal levels.

quantitative and qualitative data (see Figure 5-4). He offered several suggestions of how specific tools can be used depending on the communication goal:

- If the goal is to highlight a single key number, icon arrays or pie charts may be appropriate.

- To illustrate change over time or compare outcomes across two time points, options include barbell graphs, back-to-back charts, or histograms.

- To compare variables, scatter plots, heat maps, and line graphs can be effective.

- Qualitative data and narrative content can be visualized meaningfully using pull quotes, images, icon arrays, Venn diagrams, timelines, social network mapping, sentiment gauges, journey mapping, and storyboarding.

Standley highlighted storyboarding as a particularly valuable technique that allows researchers to align the logic model with the theory of action in crafting a story. He also cited quote graphics, used strategically on social media platforms, as a simple yet powerful tool to share themes in ways that resonate with audiences. He encouraged workshop attendees to explore Stephanie Evergreen’s (2019) work on how evaluators and researchers can improve the presentation of findings through appropriate illustration selection.

SOURCES: Presented by Corbin Standley on April 29, 2025; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention; Evergreen (2019).

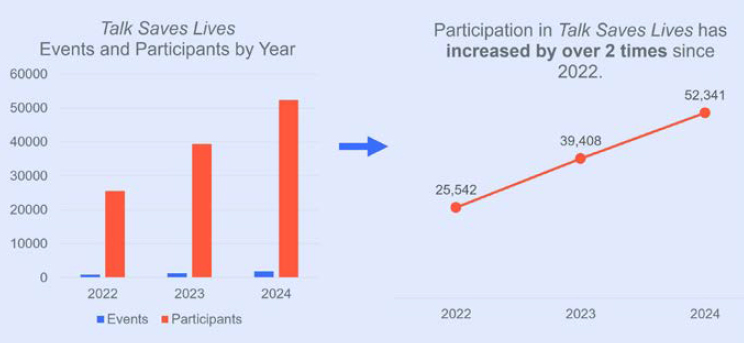

To illustrate how to improve the effectiveness and clarity of data visualizations, Standley next showcased a “before and after” example from the AFSP flagship program Talk Saves Lives (see Figure 5-5). He noted that the bar graph on the left leaves it up to the audience to interpret that the takeaway message is participation in the program increased over the last several years. The line graph on the right outlines the exact numbers and provides the takeaway in the graph title—participation in Talk Saves Lives has increased by over two times since 2022.

Standley reiterated the importance of selecting visualization tools that offer both clarity and meaningful interpretation, drawing on participant reflections shared AFSP’s International Survivors of Suicide Program to illustrate this point (see Figure 5-6). In the word cloud example on the left, we can see that participants used terms such as hope, healing, and connection appear prominently, but the visualization offers little insight into what those words actually meant to participants. The thematic quote panel on the right provides that missing context by presenting direct quotes that reflect shared experiences and emotions—for example, the sense of connection and understanding that arises from being among others who understand the unique grief of suicide loss. These survivor voices tell a more powerful story than a word cloud alone can convey.

Standley concluded by emphasizing that this example illustrates why visual storytelling should be planned from the outset. Building visualizations into the broader dissemination strategy can ensure findings are not only seen but understood in ways that resonate with the intended audience.

SOURCE: Presented by Corbin Standley on April 29, 2025; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (2024).

SOURCE: Presented by Corbin Standley on April 29, 2025; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (2024).

PANEL DISCUSSION AND AUDIENCE Q&A

Following Niederdeppe’s and Standley’s presentations, Mary Cwik (Johns Hopkins University), Novalene Alsenay Goklish (Johns Hopkins University, Brandi Jancaitis (Virginia Department of Veterans Services), Richard McKeon (SAMHSA), and Itzhak Yanovitzky (Rutgers University) joined them for the moderated panel discussion. Bernice Pescosolido (Indiana University; member, workshop planning committee) served as the moderator for this discussion. Panelists responded to guiding questions on the following topics: tailoring communication to different audiences, evaluating communication strategies, and sharing academic literature effectively.

Tailoring Communication to Different Audiences

Pescosolido began the moderated discussion by noting that this is a uniquely promising moment for public engagement, citing recent data from a representative sample in Indiana, where more than 90 percent of respondents—across a politically conservative state—expressed support for school-based mental health and suicide prevention programming. This surprising level of consensus, she said, reflects a shift in public attitudes and underscores the importance of thoughtful, inclusive communication strategies. She then invited the panelists to share examples of best practices for tailoring communication efforts and addressing the expectations of different communities, particularly in crafting messages that help audiences feel included.

Standley responded that one key focus for AFSP is the continuum of impact. Their work is trying to move individuals and the broader public from awareness to behavior change. However, he acknowledged that it can be difficult to communicate to funders, policymakers, and other stakeholders that a one-year intervention will not necessarily demonstrate measurable reductions in suicide rates at the community level.

Echoing earlier remarks by Kristen Quinlan, Standley pointed to indicators of progress, such as increased knowledge and awareness, reduced stigma and negative attitudes around suicide prevention, greater openness to discussing suicide and mental health, and growing willingness to reach out—either to support loved ones and friends who may be struggling or to seek help oneself.

Setting realistic expectations for evaluation, he added, requires recognizing that behavior change is complicated. Multiple elements must align to achieve behavior change, including awareness, knowledge, and attitude shifts, and the development of intent to change, Standley continued. How long the process of behavior change takes will vary depending on the community, the intervention, funding level, and the program’s sustainability.

Communicating clearly about behavior change while tailoring language to the audience is important for getting people on the same page.

Yanovitzky raised the distinction between tailoring and targeting. Targeting, he explained, involves trying to engage a homogenous group of people, while tailoring involves trying to make a message more relatable. The goal is engagement, not dissemination, he said. To develop tailored messaging, the first step is clarifying the communication goal, Yanovitzky stressed. The goal might be to increase knowledge, to persuade, or to guide people in navigating action, as in cases where people are already motivated to act but are not sure how to proceed. Determining the nature of the underlying communication problem or opportunity is essential, Yanovitzky noted, as different problems and opportunities call for the application of different strategies.

Tailoring should be grounded in data about the target audience—not just demographic data, which he cautioned against over-reliance on, but deeper insights into beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, and values. As an example, he referenced Pescosolido’s account of recent survey findings showing broad support for youth mental health programming in Indiana, noting that other survey data suggest support becomes more conditional when parents are asked specifically whether they would consent to depression screening for their children. He explained that concerns may differ across communities—for instance, some parents may worry about stigma in school settings, while others may have questions about how to access follow-up care. These nuances, he explained, underscore why audience research is essential to effective tailoring. It allows communicators to align goals, identify the right audiences, and understand where those audiences are—both geographically and in terms of readiness to act.

Niederdeppe emphasized the importance of engaging communities from the very beginning of program design and development. He noted that the people most interested in the results of an intervention are those who were involved in its origin, development, design, and implementation. One of the most effective ways to understand the values and needs of an audience, he suggested, is to collaborate with them from the outset in developing interventions. This ensures the intervention reflects the community’s interests, goals, and conditions at the forefront, and builds a natural audience for communicating results. While it is not always possible to have a personal conversation with every potential stakeholder, Niederdeppe reiterated a point made earlier in the session: incorporating communication strategy into the earliest stages of intervention planning—particularly by involving community partners—can help ensure that dissemination efforts are aligned, meaningful, and impactful.

Jancaitis underscored the importance of understanding the audience and directly engaging with the military-connected community through

focus groups, survey, and lessons learned. She illustrated this with an example of her work with the Virginia State Department of Behavioral Health on marketing for 988 in Virginia. Because there was not enough time to convene a formal focus group, she relied on her team—more than half of whom were military connected—to serve as an informal review panel. Their input quickly surfaced a critical issue that the contracted marketing firm had missed. For instance, they flagged an image of a 988-responder sitting in a cubicle in an open bay behind her, raising immediate concerns about data privacy and the perception of confidentiality.

Jancaitis added that using stock images can present a particular challenge in this context. Visual details such as a popped collar, missing rank insignia, or inappropriate hairstyle can erode a message’s credibility with military audiences. “It doesn’t matter how long you took to craft that message,” she said. “Nobody is reading it” if the imagery signals inauthenticity.

Jancaitis also discussed the disconnect that can arise around terminology. In clinical settings, the term “safety planning” is well understood and generally viewed as positive. But among some community members, it may instead trigger fears of hospitalization, loss of rights or benefits, or the inability to support one’s family. She stressed the importance of taking messages directly to the communities they are intended to reach, to ensure they are interpreted as intended.

She concluded with a final cautionary example. While supporting a research effort, her team assumed that having university and institutional review board approval would be sufficient to ensure community participation in a survey. That assumption proved mistaken. Community members, she said, “deconstructed every element of the survey”—work that had taken months to develop. The lesson, she emphasized, was that involving the community from the outset could have prevented that breakdown entirely.

Cwik brought up that the Johns Hopkins Center for Indigenous Health shared results with the community in addition to journals and policymakers. To utilize this momentum, her team created a large in-person event where the community members could receive the information directly from the researchers, which, she suggested, is better than the community having to gather information from the website or opening a newsletter. Cwik also noted that they made this large in-person event a celebration of the study being successfully completed: there was food, cultural singing, dancing. This study she mentioned was an elder youth program, so there were also a panel of Elders who spoke about their involvement in the program. The Center where Cwik and Goklish work also prioritized the community’s culture, having as much of the celebration as possible in Apache, with translations, as well as sharing pictures and stories about working with the Elders and how the program worked. The final thing she mentioned was that, in an effort to express data in

a creative way, one of the staff members took qualitative data from the study and created a painting of a cottonwood tree. The staff member then told an Apache story about the cottonwood tree that was related to the data gathered, which ended up being culturally congruent data.

Goklish continued discussing staff creatively discussing data by saying that having the parents and students see that their Elders were having a positive impact on the students. The data reflected this, showing that student’s self-esteem increased as well as their connection to tradition and culture. She went on to discuss that having meetings to go over curriculum and allowing the Elders to go into the schools to teach had an impact immediately, but also that a continued loop of input from the Elders, the community, and feedback to the Elders ensures that the results and impact are felt both within the community and with the staff at the schools.

Evaluating Communication Strategies

Pescosolido asked how programs have approached evaluating their communication strategies. McKeon said, in terms of communication strategies, his team invested in trying to do focused research to get feedback from demographic groups who are at greater risk as well as a group of people who had a history of lived experience around suicide (in terms of a history of suicidal thoughts and attempts). The feedback around these focus groups (for example, one subgroup was concerned about if police would be sent/would someone end up hospitalized?) helped craft messaging to connect with the community and ease any fears.

Yanovitzky chimed in, stating that it is important to consider how communication strategies are aligned with underlying processes of change. He went on to say that, to influence policymaking, the communicator must respect the underlying process by which policymaking occurs. Yanovitzky stated, “having [a] communication strategy focus not on why, but [on] what can you expect to happen when you communicate with your audience would go a long way in terms of influencing behaviors.” Communicators must respect the audience and the underlying process.

Niederdeppe added an important series of questions: why are the researchers evaluating communication? Is it to demonstrate benefit to a funder so that there are additional resources? That sort of evaluation, he said, demands a certain level of rigor and investment. Niederdeppe went on to ask, “how can we do this better?” He stated that a lot of organizations engage in modest, light experimentation and a-b testing. Niederdeppe recognized that while it is not the same level of rigor typically associated with peer-reviewed evidence that would justify a large investment, it does give information in real time that can inform practice.

Sharing Academic Literature Effectively

Pescosolido mentioned that academic publications don’t always disseminate in a way that researchers would like, and asked what are ways that program developers and evaluators share academic literature in a more effective way? Before turning this question over to the panel, she shared her experience in that special issue publications seem to draw more academics and policymakers, as opposed to one-off articles.

Standley agreed with special issues being more attractive to academics and policymakers, but expanded, stating that publishing in a journal outside the field of suicide prevention, suicide research, and death studies is key, as publishing in those journals is “preaching to the choir.” Instead, he suggested, consider publishing in journals like the American Journal of Public Health, Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, social work journals, or other journals that are adjacent, but not suicide specific. Standley went on to say that these other journals may be more open to other methodologies and suggested that a researcher might want to target methodological journals that publish participatory community engaged research or ones that publish mixed-methods and qualitative research.

Yanovitzky spoke to questions around implementation: how does someone navigate complex funding and legal environments? If someone was able to recruit and meet targets for clinical trials, especially in groups that are challenging to recruit, how did they do it? What did they do? How did they put their information out there? Yanovitzky said, “I want to encourage a lot of program relevant data, that maybe they’re not measuring, maybe it’s anecdotal. There’s a lot of value to bring to the surface, so we can all benefit from that and move to [the] implementation side.”

Pescosolido asked panelists to reflect on how grant programs might support grantees to evaluate local programs to facilitate that kind of publication. McKeon commented on communications to policymakers, that it is important to keep in mind the time frame for a policymaker is very different than other people, that they typically only have four to eight years, so they need to see more rapid change. He went on to say that when people are advocating for money, there is a tendency to talk about possibilities and, with suicide prevention’s complexity and time-intensive nature, it is important to use a combination of metrics. McKeon suggested matching data with stories, utilizing compelling examples to make it clear why this initiative or intervention is important. He also noted that, for policymakers, it is important to focus on how your intervention will reduce suicide in the United States, rather than at a global level. For example, someone could say “these things reduced suicide in the White Mountain Apache community” or “this reduced suicide in the Henry Ford Health Care System” but maintain the goal of applying it in other communities.

Jancaitis spoke about the difficulties they are facing with their research grantees. She noted that it took a lot of time to work through academic approvals, hiring a team, working around student schedules, and their research is about to blossom into findings that can be used. However, she described challenges with figuring out how to package this research into a “toolkit-type digestible” and usable format, while keeping it completely free and accessible. She mentioned that a lot of research teams were unwilling to work with them since there are so many rules around what constitutes proprietary information. Jancaitis closed by saying that, as the funder, it was their responsibility to put in the proposal that their research should be free and accessible for grantees.

Audience Q&A

During the audience Q&A, several participants raised important questions about communication strategies, the role of credible messengers, and how to translate research findings into accessible tools for communities and policymakers. Panelists responded by reflecting on the challenges of crafting effective messaging, ensuring cultural relevance, and building trust with diverse audiences. The discussion also highlighted opportunities to align communication approaches with shared values and strategic partnerships.

Crafting Effective Messaging and Identifying Credible Messengers

Matthew Miller (VA Office of Suicide Prevention) commented that the general purposes for the communication might be agenda setting, persuasion, and coalition building, but that wasn’t necessarily practice in federal government or how we think in public health or in suicide prevention: “We think in terms of realizing data, [we] don’t think in terms of crafting a message,” he stated. He went on to say that crafting a message could be viewed as manipulative but was curious on the panel’s thoughts around the role of federal government, public health, suicide prevention, and crafting a message versus just releasing data.

Niederdeppe responded by first acknowledging that he did not mention in his presentation who should be doing the communication, which is central. He said that, in the last 10 to 15 years, there has been a steady erosion of trust in the federal government, public health, and in messaging in general. Niederdeppe emphasized that the federal government is not always best positioned to be the voice of communication; therefore, the question becomes: who is positioned to do that communication in a credible way, reaching the correct audience? Despite there being no one-size-fits-all solution, one thing communication science teaches, he said, is that an

unexpected messenger can have a lot of value—for example, communicating in a way that defies expectations based on one’s political orientation, which is connected to the coalition-building idea. Niederdeppe went on to explain that to identify people as credible messengers, the person must share a goal of implementing a policy or program, even if they have different reasoning but are willing to partner and are able to communicate resonantly and with values consistent with the group. He also mentioned that there is tremendous value to just having data for the purposes of planning and strategy, but that the researcher loses control once the data are put out into the public and can be mis- or re-interpreted in any number of ways, so decisions about when and how to release and frame data can be complicated.

Yanovitzky joined in on the conversation and stated that while he does not like to respond to questions before doing due diligence (which, in this context, means performing problem analysis, audience analysis, and pre-testing), his team has protocols to figuring out trusted communicators. He said that they do not assume who these communicators are, even still trusted voices like the CDC, he would rather find out for himself who these people are. Sometimes, Yanovitzky stated, he utilizes intermediaries or people from the community. He works with the National Alliance of Mental Illness and can get data from the researcher, use the data, and interpret the data, then tell stories about the data in terms of how it is making an impact on the community. “Here is the point. Data don’t speak for themselves. If you don’t speak for data then there’s an information vacuum, and anybody can go and interpret the things. […] I can show a graph and manipulate the scale in a manner that makes a small change [look] like a big change. That’s manipulation.” Yanovitzky further stressed that, as long as there is the notion that there is an ethical standard (i.e., the third party looking at the report or if there are disclaimers about how data were interpreted), credibility is shown that way—however, there is no way to ensure credibility; rather, the target audience has the power to decide that. He went on to say that if someone wanted to be strategic, he suggested that they use scientific and robust tools for answering the questions who, how, and how we package information in a way that can facilitate comprehension.

Standley added that he often trains evaluators and researchers on how to share findings with policymakers, since it is very different than with community communication. One thing he suggested is called the “taxonomy of research use” which means understanding research evaluation data is one of many sources of information that policymakers are using to make decisions and that policymakers often use research in many different ways. Policymakers have two ways they use information: conceptual use (to shape the conversation and understand the scope of an issue) and instrumental use (to understand an issue well enough that they can propose legislation or support appropriations to target that issue). Standley noted that researchers

and evaluators should act as mindful and honest information brokers when talking to policymakers, staffers, or others, especially in situations where data may be used tactically to support decisions that were made before the data were reviewed.

Leveraging Shared Values and Strategic Partnerships

Another audience member mentioned that, as a Staff Sergeant Parker Gordon Fox Suicide Prevention Grants Program awardee, they often leverage Standley’s planning process. They mentioned that, though they present themselves as fairly liberal, they grew up on a farm hunting and fishing but also own a firearm and are a veteran. This audience member stated that they think the most effective route for communication around firearm safety is having specialists present the data around safety, rather than talking about policy to prevent ownership. They also mentioned that there are more opportunities when discussing safety this way, because they could partner with the National Rifle Association (NRA) since there are shared interests. This shared interest also serves as an avenue for the NRA, or similar partners, can present data to populations of interest on the researchers’ behalf to garner interest and buy-in. The audience member said that they have tried this method and ground level testing in different populations which has been pretty successful.

REFERENCES

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. (2024). Supporting those affected by suicide—the impact of International Survivors of Suicide Loss Day. Impact Spotlight, 3. https://www.datocms-assets.com/12810/1732043814-14842_afsp_impact_spotlight_issue3_m1.pdf

Evergreen, S. D. H. (2020). Effective data visualization: The right chart for the right data (2nd ed.). Sage.

McDonagh, L. K., Saunders, J. M., Cassell, J., Curtis, T., Bastaki, H., Hartney, T., & Rait, G. (2018). Application of the COM-B model to barriers and facilitators to chlamydia testing in general practice for young people and primary care practitioners: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 13(1), 130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0821-y