Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) Education and Outreach (2025)

Chapter: 5 Develop Practitioner Guidance for Delivering ADAS Education and Training

CHAPTER 5

Develop Practitioner Guidance for Delivering ADAS Education and Training

During Phase II of the project, the research team developed guidance for practitioners who aim to deliver ADAS education or training. Their work was informed by the findings from Phase I.

The review activities indicated a lack of evidence in the scientific literature that supports the effectiveness of ADAS training outside of research settings and little guidance from SDOs to guide practitioners who want to provide ADAS education or training. In addition, the review of existing ADAS educational materials resulted in several findings that indicate it may be challenging for practitioners to use them. These materials generally fall into two categories.

One category is materials that provide only generic, high-level information about ADAS, which cannot give a learner a full and complete understanding. For instance, procedural information was frequently missing due to its vehicle-specific nature.

The other category mainly included materials from manufacturers, which presented many specific details for multiple specific ADAS systems. These materials often combined multiple types of ADAS in one section or grouped different ADAS under umbrella terms (e.g., forward collision prevention), which could confuse learners or lead them to conflate systems. These materials also required the learner to determine on their own which information is pertinent to their specific vehicle.

Across both categories of materials, ADAS information rarely stated learning objectives or identified the intended audience for the materials. Very few materials presented learners with an opportunity to apply or assess their knowledge. Materials contained many potential inaccuracies, some of which could be very challenging to identify without existing knowledge or experience with ADAS.

Finally, the research team observed that practitioners who might use the guidance developed during this project will represent different organizations that will have different motivations and aims for providing education to different audiences. The presentation of ADAS information will need to be tailored according to the audience and the opportunities available for the organization to connect with each audience.

For these reasons, the research team developed a process to guide practitioners who aim to provide ADAS education or training through identifying and customizing ADAS learning materials to fit their organization’s aims, audience of learners, learning objectives, and resources. The guidance to practitioners is presented in two deliverables: a practitioner guide and a webinar.

5.1 Approach

Development of the process for delivering ADAS education and training was informed by the findings from Phase I and two case studies that simulated how practitioners might provide ADAS education or training for the featured population and ADAS (i.e., new users of ACC). The research team intentionally selected characteristics of each case study to illustrate the robustness of the process in different scenarios (see Table 14). The first case study considers how a state transportation agency might develop new learning materials to provide education about ACC to drivers of passenger vehicles. The second case study demonstrates how the process could be applied to identify existing materials that could be incorporated into

company-provided training about ACC for operators of a specific model of CMV. In this way, practitioners can review both case studies and determine which aspects may apply to their given situation. For example, a practitioner might be interested in general ADAS education for commercial drivers, so parts of both case studies could be useful.

Table 14. Characteristics of case studies featuring new users of ACC.

| Characteristic | Case Study 1 | Case Study 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Driver type | Passenger vehicles | CMVs |

| Practitioner organization | Government (state transportation) agency | Business |

| Aim | Education | Training |

| Materials | Create new learning materials | Identify existing materials |

5.1.1 Initial Draft of Process

The research team identified and reviewed various examples of guidance for practitioners, including guides, checklists, and toolkits. Though most of the examples were identified during a specific search for practitioner guidance (with an emphasis on CRP products), some examples had been identified by the team during Phase I or shared with the team by members of the SME panel.

Each team member evaluated a set of guidance products and documented useful information regarding content, layout, level of detail, tables, and figures. This activity helped the team identify desired qualities and informed the organization of this project’s practitioner guide.

Next, the team created a first draft of the sequence of steps practitioners can follow to provide ADAS education and training. The team planned to modify the framework (shown in Figure 4) developed in Phase I to create a tool for practitioners. Although the framework was helpful for documenting the landscape of existing materials, it did not translate well into direct guidance for practitioners. The various concepts of the framework were integrated into different steps of the draft process.

This early draft of the process included concepts such as:

- The process of providing ADAS education is unlikely to be linear and may consist of several rounds of iteration.

- The process will be constrained by resources such as effort and time.

- The process should begin by defining the purpose of providing ADAS education, including identifying a specific ADAS, an intended audience, and objectives.

In addition, the draft process also highlighted areas where practitioners would benefit from specific guidance:

- How and where to find ADAS educational materials

- How to evaluate whether educational materials fit with the practitioners’ purpose and constraints

- How to modify material to better fit the purpose

- How to solicit feedback on the educational material to better understand if it will fit their needs

5.1.2 Passenger Vehicle Case Study Exercise

The research team began the exercise for the first case study. The desired case study characteristics (see Table 14) were fleshed out into a scenario that established details about the practitioners, their organization, motivations, and aim for providing education about ACC to new users. Each researcher played the part of different stakeholder people and roleplayed those during the exercise, which played out over several weeks.

As the team worked through the steps of the draft process in the context of the case study scenario, they identified areas where steps were missing or steps that required additional content. This process also identified several opportunities to provide practitioners with tools or resources, including the Resource Identification Tool, the Content Organization Tool, and the Aid for Identifying Opportunities for Confusion in ADAS Information. In parallel to the case study exercise, the team drafted content and tools for the guide and performed several iterations of drafting content to describe steps in the process and revising content based on the experience of applying the guidance to the case study scenario.

5.1.3 CMV Case Study Exercise

To prepare for the second case study, the research team attempted to contact several individuals and companies associated with the CMV industry, including trucking companies and associations, fleet managers, a manufacturer, a federal agency, dealerships, and manufacturers. The team conducted one formal interview with an associate from a commercial vehicle manufacturer and held a few informal conversations with an employee from a trucking company. In addition, the research team consulted the draft Recommended Practices document from TMC titled Optimization of Driver Training for ADAS and reviewed updated information from FMCSA’s TechCelerate Now program. Finally, the research team identified numerous online learning materials for ADAS in CMVs.

The research team followed a similar process for this case study, developing a detailed scenario and role-playing different stakeholder perspectives. This case study involved searching for materials and a training objective, which highlighted additional aspects that needed to be added or better explained in the process description and informed the addition of the ADAS Information Source Tracker.

5.1.4 Feedback on Process and Practitioner Guidance

As the development of the practitioner guidance has neared completion, the research team obtained feedback from three different entities. In August 2024, the research team submitted a speaker proposal for the 2025 Lifesavers Conference on Roadway Safety. The proposed talk included a case study illustrating how tools and strategies from the draft practitioner guide can be applied to education for ACC and stated that the Lifesavers audience would be asked to provide their feedback. The proposal was accepted.

In preparation for the presentation at Lifesavers, the research team gave a presentation to four other ADAS technical experts at DSRI. The presentation introduced the project, gave an overview of Phase I findings, and introduced the steps of the process. After each step was presented, the corresponding information from the case study was presented. The DSRI technical experts gave substantive feedback on the steps of the process, the level of detail, and suggested reorganization of the presentation to introduce the whole process and then present the whole case study. This feedback led to a reorganization of the presentation and the practitioner guide itself. The research team integrated feedback from DSRI technical experts by reducing the number of slides, reducing the amount of text, and including more figures into the Lifesavers presentation.

At the Lifesavers Conference, two members of the research team presented it to an audience of approximately 30 practitioners. These practitioners confirmed that their organizations would likely use a team approach on an ADAS educational and training effort. Nearly all practitioners agreed that they would be able to identify someone with ADAS expertise and to work with a content creation team to develop the learning materials. The Q&A portion of the session revealed that practitioners are aware that ADAS are

continuously changing and that the effort to keep training and educational materials up to date is a significant barrier. Several noted the lack of standardization across manufacturers and the lack of requirements for manufacturers to provide education or training to consumers and expressed a desire for standardized content. One practitioner noted hesitancy to help their agency’s constituents identify information for the ADAS on their vehicles due to potential liability. Another practitioner expressed appreciation for the Resource Identification Tool.

After incorporating the feedback from Lifesavers attendees, the research team prepared a summary of the Practitioner Guide contents, highlighting the Process for Providing ADAS Education and Training. The summary and a link to a brief survey were distributed to the SME panel. Seven members of the panel provided substantive comments, which the research team incorporated into the draft practitioner guide. Overall, the SME panel provided positive feedback about the clarity and flexibility of the Process for Providing ADAS Education and Training. They noted that the steps were logical and clear and that the “team approach” to providing ADAS education and training was a strong approach. A member of the SME panel noted that a large organization should be able to follow the outlined process but that it may be difficult for a smaller organization to complete this task as they may have fewer resources. To address this feedback, the case studies demonstrate how different organizations can take different approaches to providing ADAS education and training based on their resources and objectives.

5.2 Practitioner Guide

This document provides practitioners with guidance about how to identify, create, or modify ADAS materials to achieve their goals and objectives for providing ADAS education or training. The guide begins by summarizing the findings from the research team’s review of informational sources, standards, and the scientific literature. Next, the guide describes a process for practitioners to define learning objectives, find materials, evaluate whether the materials fit the practitioners’ objectives, select content for learning materials, and plan for dissemination of the learning materials. Finally, the practitioner guide includes two case studies to demonstrate how the process can be applied.

5.2.1 Process for Providing ADAS Education and Training

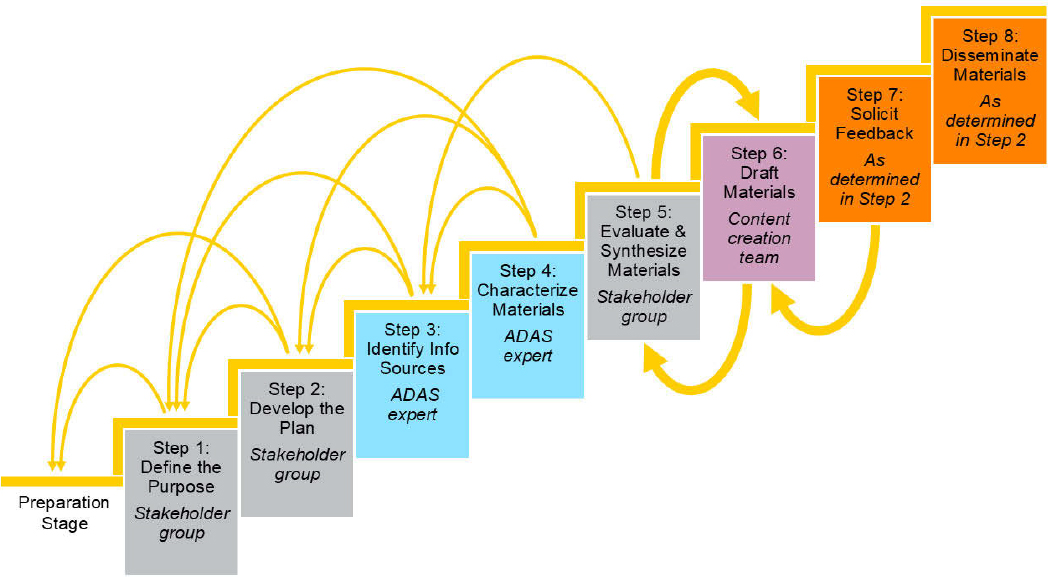

The Phase I findings illustrate that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for ADAS education and training. Practitioners who aim to provide ADAS education or training would benefit from selecting or customizing ADAS education or training materials to fit their organization’s aims, audience, learning objectives, and resources. As a result, the research team developed a process that practitioners can follow to provide ADAS education and training tailored to their specific needs. The process, shown in Figure 6, is not intended to be prescriptive. Practitioners may add, remove, or execute steps in a different order based on their needs and constraints. In addition, the process is iterative. At each step (as represented by the arrows), practitioners verify that their decisions reflect the objectives, plan, and constraints that they previously identified, or they revisit previous decisions to make adjustments. The process is flexible and can be used to evaluate existing materials or to gather information to create learning materials.

The process contains a preparation stage and eight steps.

- In the preparation stage, practitioners clarify the organization’s rationale for providing information about ADAS, identify resources that the organization will provide for the effort, and determine who will be involved in the process.

- In Step 1, practitioners identify the intended audience, learning objectives, and ADAS features to include in the learning materials.

- In Step 2, practitioners develop a plan for delivering (i.e., when, where, and how) ADAS education. In Step 3, practitioners specify the ADAS content needed for the learning materials, then plan and

- conduct a search to identify sources of ADAS information that include content related to the identified learning objectives.

- In Step 4, practitioners review the identified information sources (e.g., ADAS educational material) and extract content related to the learning objectives.

- In Step 5, practitioners evaluate and synthesize the information extracted in Step 4 and provide the specifications for the learning materials to the content creation team.

- In Step 6, practitioners review the learning material designed by the content creation team.

- In Step 7, practitioners solicit feedback for the learning materials from representatives of the target audience.

- In Step 8, the learning materials are disseminated to the target audience.

5.2.2 Tools and Resources

The research team developed several tools and resources to assist practitioners. Three tools summarize selected findings from Phase I to help practitioners identify and evaluate sources of ADAS information. Two tools help practitioners document the search for materials and identify and organize content that is aligned to the learning objectives.

- Observed Names for Selected ADAS – Practitioners can use this table to identify common names for ADAS and other terms that can be used to search for resources.

- ADAS Information Source Tracker – Practitioners can modify and use this tool to maintain a record of search efforts and findings.

- Resource Identification Tool – Practitioners can use this tool to inform their search strategy for ADAS educational materials. The tool collates the ADAS educational materials reviewed in 2023 during Phase I of this project.

- Content Organization Tool – Practitioners can modify and use this tool to identify, review, and organize ADAS content that aligns with the learning objectives.

- Aid for Identifying Opportunities for Confusion in ADAS Information – This tool provides examples to help practitioners identify opportunities for confusion.

5.2.3 Passenger Vehicle Case Study

A state agency decided to educate drivers about ACC, emphasizing the driver’s responsibilities and awareness that the system has limitations. The audience for the learning materials were individuals registering or renewing their vehicle registration. Educational materials included printed information that was mailed with vehicle registration materials and a website. A group of stakeholders, including an agency employee with ADAS expertise who reviewed numerous information sources, identified content to address each of the learning objectives. The content creation team developed the mailer and website, incorporating feedback from the stakeholders and audience members to ensure they were visually appealing and easily understood. One of the stakeholders gathered feedback on the materials from DMV visitors. Information cards were distributed with vehicle registration materials for about 10 months. Website metrics were tracked monthly, and the webform for submitting questions was removed after 18 months.

5.2.4 CMV Case Study

In the CMV case study, practitioners from a trucking company determined how to provide training for ACC to commercial motor vehicle drivers in their fleet who would be driving a specific vehicle. Company leadership wanted the employee drivers who drove new trucks equipped with ACC to understand how to use it, when it is appropriate to use it, and the potential benefits of using ACC (i.e., lower driver stress and fatigue and better fuel efficiency). A group of stakeholders from within the company identified and reviewed materials provided by the manufacturers of the vehicle and the ADAS and selected materials to achieve their company’s aims. The practitioners created a training program that included selected videos and other materials from the ADAS manufacturer, in-vehicle training with the company’s training specialists, and evaluation of the learner’s understanding.

5.3 Webinar Materials

This presentation is updated from the materials presented at the 2025 Lifesavers Conference for Roadway Safety. The webinar begins by summarizing key findings from Phase I. Then, the research team gives an overview of the process, followed by describing the considerations and decisions associated with each step of the process. Lastly, the steps of the process are revisited through the lens of the case study. If suggested by the BTSCRP-26 panel, the research team will develop a brief survey to be administered at the end of the webinar to collect participant feedback.

5.4 Future Research

The technical memorandum provides a summary of the activities conducted by the research team to complete the project objectives. The future research needs described in the technical memorandum were formulated based on project findings during Phase I of the project. The first research need is to establish and validate a measurement tool that can be used to assess drivers’ understanding of ADAS. The lack of a validated measurement tool makes it difficult to ensure the study results are reliable, comparable, or valid. The second research need is to assess the efficacy of ADAS education and training on drivers’ understanding, use, trust, and perceptions of ADAS using validated measurement tools. Specifically, additional research findings could elucidate when (i.e., before, during, or after initial use, after becoming familiarized with the vehicle, or after experiencing edge case scenarios), how long (i.e., duration), or how often (i.e., frequency) ADAS training should be provided to drivers of passenger and commercial vehicles.

5.5 Implementation Plan

The team developed a technical memorandum detailing a plan to implement research findings and products detailed in this report. In the plan, the research team identified a target audience and potential champions for using the practitioner guide. The plan is divided into two tasks. The first task is to develop workshop materials that can be used to guide trainers or educators to apply the process outlined in the practitioner guide. The second task involves using the materials to conduct a workshop to demonstrate the process and tools outlined in the guide, to develop or modify ADAS training and education materials, and to solicit feedback about the guide. Feedback could be used to improve the process and tools in the guide and identify barriers to providing ADAS education and training.