The Future of Youth Development: Building Systems and Strengthening Programs (2025)

Chapter: 5 OST Workforce

5

OST Workforce

The quality and competency of the workforce supporting out-of-school-time (OST) programs are important elements of program quality, contributing to young people’s level of engagement in programs and the impact of programs on their outcomes. Staff are a critical piece of young people’s experiences in OST programs. The relationship between OST staff and participants for their experiences and outcomes is discussed in more detail in Chapters 6 and 7. This chapter1 focuses on the staff themselves—offering a picture of their multifaceted role, the beliefs that inform their approaches to working with children and youth, and the competencies and practices that may foster positive youth development. The committee follows the path of youth development practitioners in OST settings, discussing motivations, educational background, and experiences that lead individuals to enter the field of youth development, as well as often-cited challenges that push them to leave their job or the field altogether. The chapter ends with discussion of opportunities to strengthen the career trajectories of youth development practitioners to create more stable and high-quality OST settings for children and youth.

___________________

1 This chapter was greatly supported by a commissioned paper authored by two researchers: Dr. Bianca Baldridge, Harvard University, and Dr. Deepa Vasudevan, American Institutes for Research.

Key Chapter Terms

Direct-service or frontline staff: Staff who work directly with youth and deliver programs, supports, and services.

Youth development practitioner: Adult leaders who guide youth through social, educational, and personal development, often in informal educational spaces. This includes professionals and volunteers.

Youth work: Activities of a social, cultural, educational, or political nature conducted by, with, and for young people.

PROFILE OF THE YOUTH DEVELOPMENT WORKFORCE

The contexts, populations, and settings in youth development are varied—thus, there is no narrow or universal definition of the profession. However, the committee’s review found that the profession centers on fostering the holistic development of children and youth, and that youth development practitioners are adult leaders who guide children and youth through social, educational, and personal development within informal educational spaces. They operate within family, community, and societal contexts, emphasizing a developmental-ecological perspective that underscores the interplay between individuals and their physical, social, cultural, and political surroundings (Freeman, 2013; Fusco et al., 2013; Krueger, 2002).

Throughout the report the committee uses the term youth development practitioner; however, those who engage in this work may be recognized by other titles, including but not limited to youth worker, informal educator, afterschool practitioner, teaching artist, coach, or counselor. Youth development practitioners operate within many youth-serving settings across many sectors, including school districts, community-based organizations, United Ways, cultural institutions such as libraries and museums, detention centers, recreation and parks, faith-based institutions, group homes, and other spaces (see Figure 4-1 in Chapter 4).

According to the Association for Child and Youth Care Practice (n.d.), roughly 2.53 million youth development practitioners work in the United States. (For comparison, in 2022, public schools in the United States employed 3.2 million full-time equivalent teachers [National Center for Education Statistics, n.d.].) Still, this count of youth development practitioners may not fully reflect the workforce’s size, as many volunteer and part-time positions span various locales where young people are confined or need support (Baldridge et al., in preparation). In addition, many professions would not be counted because of their context, though youth development is a key part of their job; for example, teen librarians spend their days supporting

youth development, but their profession is listed as librarian. Indeed, taking the frame of “allied youth fields,” Robinson and Akiva (2021) suggest that professions associated with supporting youth development include child welfare, juvenile justice, police, mental health, housing, transportation, and others. In this sense, far more professions are involved in youth development than in teaching.

No sources provide population-level data on youth development practitioners in the United States. Therefore, the committee examined existing survey data to better understand practitioners’ characteristics and experiences. Organizations such as the National AfterSchool Association, as well as independent researchers, have conducted surveys to gauge the breadth of experiences of youth development practitioners. The most recent and largest survey to date is the Power of Us Workforce Survey (American Institutes for Research [AIR], 2025), a national cross-sector survey of over 10,000 paid staff and volunteers who work with children and youth outside of classroom settings. Without population-level data, it is not possible to assess the extent to which this sample represents the youth development workforce, but the survey helps to build a national profile of these workers (see Table 5-1). Survey results indicate an overrepresentation of females and of White youth development practitioners (AIR, 2025). Most respondents hold full-time positions, and most are located in metropolitan areas.

Roles and Responsibilities

Professional preparedness for youth development practitioners entails content-based knowledge and preparation, knowledge and experience engaging in youth development practices, and managerial adeptness. The Power of Us survey outlined common roles and titles that youth development practitioners may hold in OST settings (AIR, 2025):

- An organizational leader (e.g., executive director, officer, president) leads the organization or a major team at the organization.

- A program leader (e.g., program manager, program director, program coordinator, youth development manager) oversees the development, design, and implementation of one or more programs, supports, and services to youth at the organization.

- A site leader (e.g., site director, camp director, club manager, youth minister, youth librarian, head coach) oversees the implementation and supervises the delivery staff at a site.

- Frontline staff (e.g., instructor, youth development professional, activity specialist, camp counselor, coach, museum educator, childcare provider) work directly with youth and deliver programs, supports, and services at the organization.

TABLE 5-1 Select Characteristics of Respondents to the Power of Us Workforce Survey

| Characteristics | Survey Respondents |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–25 Years Old | 19% |

| 26–39 Years Old | 37% |

| 40–54 Years Old | 28% |

| 55 Years and Up | 14% |

| Race/Ethnicitya | |

| American Indian | 1% |

| Asian | 3% |

| Black or African American | 14% |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 17% |

| Middle Eastern | <1% |

| Native Hawaiian | <1% |

| White | 56% |

| Two or More Races/Ethnicities | 7% |

| Unsure | 1% |

| Not White | |

| Not White | 43% |

| Sex | |

| Female | 74% |

| Male | 21% |

| Position Type | |

| Full Time | 71% |

| Part Time | 20% |

| Other | 9% |

| Tenure in the Field | |

| Earlier Career (<15 Years) | 53% |

| Sustained Career (>15 Years) | 45% |

| Work Locationb | |

| Metro Area | 80% |

| Nonmetro Area | 20% |

| Leadership Position | |

| Yes | 73% |

| No | 27% |

a Respondents could select more than one race/ethnicity, so percentages will not sum to 100%.

b Metro area and nonmetro area are defined based on the rural-urban continuum from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (Economic Research Service, 2025).

SOURCE: Generated by the committee, with data from AIR, 2025.

In practice, the lines between these roles are often blurred, with practitioners wearing many hats and their job expectations evolving to meet the needs of the programs, which can add to the difficulties in defining this profession. Most of the respondents in the Power of Us survey—regardless of role—reported that they work directly with youth (AIR, 2025). It is also common for youth workers to share both anticipated and unanticipated job responsibilities, which can range from activity planning and engaged supervision to event planning, meal preparation, transportation, custodial work, and grant writing (Baldridge, 2018; Bloomer et al., 2021; Vasudevan, 2019). In addition, youth development practitioners might take on family-like responsibility for their youth participants—as first responders in emergencies, advocates at school and court, and both temporary and long-term legal guardians (Bloomer et al., 2021; Starr, 2003; Vasudevan, 2019). They often self-identify as multihyphenates (e.g., artists and youth workers), taking on “boundaryless” constructions of their professional identities, in terms of time commitment, occupational role development, and engagement approaches with young people (Vasudevan, 2019). Researchers have raised concerns that youth workers often have to play the role of hero—or take on too many roles in the lives of youth—without adequate training, support, professional mentorship, or sense of being valued in the work (Anderson-Nathe, 2008; Baldridge, 2019; Baldridge et al., 2024; Van Steenis, 2020; Vasudevan, 2019).

In public sessions with OST staff,2 the committee heard that many were accustomed to taking on formal and informal responsibilities as part of their role within the program, including organizing programming, managing funding and compliance, engaging with families and communities, and negotiating resources for transportation and food, among others. Despite the mental and physical exhaustion that youth development practitioners may face, “they are still fairly engaged and feel a high degree of pride and accomplishment in their field” (Barford & Whelton, 2010, p. 281). For example, one program leader shared:

I come and speak at panels like this, I respond to funders, and then I change clothes and learn how to make slime with first graders. [. . .] We all wear a lot of hats because if we had an immense amount of funding, we would be able to not do both of those things in a 2-hour period. But we do learn a huge number of skills through this work because we do have to wear as many hats as we need to wear to make sure that we are accomplishing our goals.

___________________

2 Recordings of these sessions can be found at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/41823_02-2024_the-experiences-of-youth-and-practitioners-in-afterschool-programming-a-public-information-gathering-session-of-the-committee-on-out-of-school-time-settings and https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42554_04-2024_the-experiences-of-youth-and-practitioners-in-afterschool-programming-part-ii. For a proceedings in brief, see National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2024).

Beliefs and Practices

As with their occupational roles, youth development practitioners hold diverse, multifaceted identities and belief systems that inform their approaches to their work (Baldridge, 2018; McLaughlin et al., 1994; Noam & Bernstein-Yamashiro, 2013; Vasudevan, 2019; Walker & Larson, 2006). Beliefs about children and youth and the systems they navigate influence their everyday work with young people and, consequently, young people’s experiences within OST programs. Some studies have illuminated that many practitioners use ecological, system-based thinking and actively resist individualistic savior narratives about their work with children and youth living in poverty and from marginalized3 communities (Baldridge, 2014; Ross, 2013; Singh, 2021; Travis, 2010). However, Starr (2003) also documented that youth workers can take on savior mentalities in some cases, as well as deficit-oriented views of youth and families. Fusco et al. (2013) and Baldridge (2020a) argue that some feel obliged to take this approach based on the framing and requirements of directors and funders. These underlying beliefs influence how participants are treated in OST programs and can translate to negative experiences and decreased engagement with programs (Anderson & Larson, 2009; Baldridge, 2019; Fusco et al., 2013; Starr, 2003).

Early research documented common traits, beliefs, and practices of youth workers (Halpern, 2002; Hirsch, 2005; McLaughlin et al., 1994); however, the study of everyday youth work practices and on-the-job experiences is limited and in need of deeper inquiry (Larson et al., 2015). Youth development practitioners often draw on practice-based wisdom that informs their everyday approaches to connecting and relating to young people (Baizerman, 2013). Scholars have studied the complexity of practice-based dilemmas that youth workers must confront daily and their strategies to address ethical issues (Walker & Larson, 2006).

Core Competencies

Core competencies include the knowledge, skills, and personal attributes needed to create and support positive youth development settings (Astroth et al., 2004). In general, youth development researchers agree that staff characteristics are critical to high-quality youth development programming and

___________________

3 In a scoping review of 50 years of research, Fluit et al. (2024) synthesized an integrated definition of marginalization as “a multifaceted concept referring to a context-dependent social process of ‘othering’ where certain individuals or groups are systematically excluded based on societal norms and values, as well as the resulting experiences of disadvantage” (p. 1). The authors note that both the process and outcomes of marginalization can vary significantly across contexts (Fluit et al., 2024). See Box 1-3 in Chapter 1.

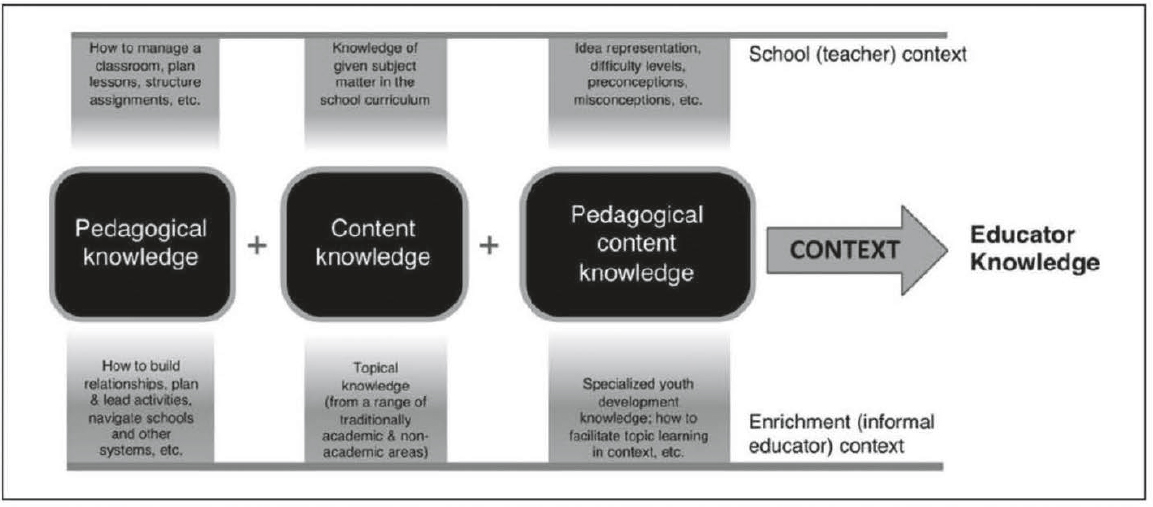

the experiences of children and youth, but there is no consensus around what those characteristics are or how youth development practitioners should best acquire them (Astroth et al., 2004). Given their varied roles (e.g., planner, facilitator, trainer, mentor, counselor, manager, supervisor), practitioners may require a broad range of competencies. According to Larson et al. (2015), “The work of running a program and facilitating youth development is more complex and multidimensional than is generally appreciated” (p. 74). Vance (2012) depicts three forms of youth development practitioner knowledge, building on the model of teacher knowledge from Shulman (1986): pedagogical knowledge, content knowledge, and pedagogical content knowledge. Akiva et al. (2023) lays this out as a generalized model of educator knowledge. As shown in Figure 5-1, the focus in youth development (an enrichment context) is on building relationships, leading activities, navigating context, topical knowledge, and specialized youth development knowledge.

Although staff can foster motivation and engagement in youth (Chung et al., 2018), they also have the potential to decrease participation or affect young people’s experiences negatively if their practices lack quality. In recent decades, a number of organizations have made recommendations around core competencies, with similar themes, including program planning, developmentally appropriate practice, behavior management, cultural competence, and professionalism (Curry et al., 2013; Garst et al., 2019; Newman, 2020; Vance & Goldberg, 2020). The National AfterSchool Association identified similar core knowledge competencies across multiple roles and experience levels, adaptable to state standards of practice and training (Warner et al., 2017). Christensen and Rubin (2020) assessed two review articles that included over 20 competency frameworks for youth development practitioners, finding that a few competencies were least cited but likely critical for staff working with children and youth from marginalized backgrounds: mental health and trauma-informed practice, building leadership, advocacy and empowerment, and intentional cultural responsivity and humility.

As stated in the National Academies report on summertime experiences (National Academies, 2019) cultural responsiveness is a key component of intentional programming. Programs that are not responsive to students’ cultural values, beliefs, and backgrounds are, at a minimum, unlikely to attract and retain youth, and at worst could do harm. As mentioned earlier, program staff often start in the field as a program participant, so they are well situated to promote cultural and linguistic competence in programming (Baldridge, 2019). In education, for example, Perry (2019) found that there are benefits in academic performance, persistence, and self-worth when a student has a teacher who looks like them (i.e., is the same race/culture; Perry, 2019); similarly, Sanchez (2016) found positive results in mentoring studies, where mentors and mentees can create shared trust and experiences.

The same may be true in OST programs. Although they are limited, current statistics of demographics of the youth work profession do not mirror estimates of the racial demographics of children and youth in programs (Afterschool Alliance, 2020; AIR, 2025). This could pose a challenge to the authentic implementation of contextually rich, culturally responsive programming (Wallace Foundation, 2022). Chapter 6 offers further discussion of the link between program staff and cultural competence and what it means for program quality.

Bright (2015) critiques competency trainings for their potential to reproduce “structures of hierarchy and inequality, and for failing to acknowledge experiences of oppression and discrimination” (p. 32). It is equally important to value and honor the vital knowledge, skills, and abilities developed more informally through staff members’ experiences and situatedness within communities, without the assumption that knowledge must be formally acquired to be valid.

ENTRY TO THE FIELD

A small body of research shows that—like most workers in the education, care-based, and helping professions—many youth development practitioners enter the field through part-time paid or volunteer work during high school and college. Some grow up attending youth programs and feel inspired to give back, while others describe their unintentional entry into the profession through a first job (Vasudevan, 2019). This section discusses some motivations driving individuals to enter the field through formal and informal pathways.

Motivations

While those outside the profession may have notions of youth work as babysitting or a steppingstone to other careers, youth development practitioners tend to perceive their work as deeply necessary to the public good, collective well-being, and community transformation (Starr, 2003). In general, they understand their work as being “for a cause” (Starr, 2003, p. 3) and hold complex understandings of the systems in which they operate (Ross, 2013). In the words of one experienced youth worker, “We are the glue that holds communities together” (Vasudevan, 2019, p. 88). Through qualitative interviews with 20 youth practitioners, Vasudevan (2019) reports that those who stay in this workforce often express deep commitments to working with children and youth, drawing on service-oriented callings driven by place-based, social justice, spiritual, and self-reflective personal missions.

In a qualitative study of youth practitioners, Baldridge et al. (2024) report that many youth development practitioners from marginalized backgrounds cite inspiration from educators and mentors when they were youth, or a steadfast belief in the power of education and mentorship in guiding young people from marginalized backgrounds (see also Heathfield & Fusco, 2016; Starr, 2003; Watson, 2012). Many of these youth workers want to give back or pay it forward to honor the youth workers, mentors, and educators who guided their paths (Baldridge et al., 2024).

The Power of Us survey showed that most respondents joined the youth development field in their teens or early 20s because of a sense of purpose (e.g., passion, interest, mission) or personal connections (e.g., recommendations from friends or family, participation in the same or a similar program as a young person; AIR, 2025).

Education and Experience

There is no unified set of educational prerequisites or standardized training to enter the youth development field. Professionalization, in the form of standardized licensure and credentialing pathways, has been debated for decades as a path toward sustainability in the field (Borden et al., 2011; Fusco, 2012; Johnston-Goodstar & VeLure Roholt, 2013; Vasudevan, 2017). Scholars and advocates have raised concerns that standardization of practices will promote a “case management” approach to engagement with youth, thus hindering the more relational, organic, and collective aspects of youth work in practice (Fusco, 2012; Johnston-Goodstar & VeLure Roholt, 2013). Additionally, Baldridge (2020b) argues that requiring higher education and specialized youth development degrees may increase racial and class stratification in this work.

Still, youth development practitioners have a range of formal educational and training experiences (Fusco, 2012; Vasudevan, 2019). Some hold high school diplomas, while others have advanced degrees and vocational content specializations. In the Power of Us survey, 40% of respondents held a bachelor’s degree, most commonly in education (23%), liberal arts (19%), health and medical sciences (11%), business (9%), or social work (9%); the survey also revealed that a master’s degree was more common for respondents who are older, are White, serve in leadership positions, and have been in the field for 15 years or more (AIR, 2025).

Depending on their goals and purposes, some organizations require an associate’s or advanced degree; others might require a high school diploma or lived experience with a particular setting or community. Some youth development practitioners come to OST settings after gaining hands-on experience as a volunteer—for example, members of AmeriCorps, a national service program, can choose to volunteer with youth-serving organizations,

offering insight into the youth development profession and a chance to gain practical and leadership skills. Americorps Vista, in particular, places volunteers in local-level agencies and organizations that serve low-income communities (AmeriCorps, n.d.).

The practice of bringing in young local community members and former program participants as volunteers or staff has long been a practice in OST programs and continues today (Halpern, 2003). Originally an expedient and cost-effective way of staffing programs with few resources, it is now a more intentional strategy that offers older youth a pathway to leadership development and adult staff roles. As one program leader shared in a public session, “We have volunteers from three different universities that come in every day, about 40 weekly volunteers. [. . .] In the 7 years since [I started], a number of those volunteers have become staff members of the organization.”4 This strategy also benefits programs by fostering a strong sense of mission and continuing relationships between participants (Matloff-Nieves, 2007).

It should be noted that, beyond degrees, organizational condition and resources matter, as does occupational identity construction (Bloomer et al., 2021; Vasudevan, 2019). Past research demonstrates that on-the-job professional development, connection to youth, and belief in capabilities are stronger predictors of career continuity than a previous degree (Hartje et al., 2008). Choosing youth work as a profession, otherwise known as “work volition,” also matters for career continuity (Blattner & Franklin, 2017). And Vasudevan (2019) reported that those who persisted in youth development occupations often cited supportive supervisors and external mentors (e.g., college professors) who offered practical and theoretical guidance in the work. Regardless of how youth workers enter the profession, research over the last 30 years demonstrates that youth workers find joy and fulfillment in their work with youth despite the challenges and precarity that exist within the field (Baizerman, 1996; Baldridge, 2018; Halpern, 2002; McLaughlin, 2000; Starr et al., 2023; Vasudevan, 2019; Yohalem & Pittman, 2006).

RECRUITMENT, RETENTION, AND ADVANCEMENT OF STAFF IN OST SETTINGS

Despite reports of high job satisfaction and a desire to stay in the workforce long term, many youth development practitioners leave their positions just after a few years because of numerous challenges (Halpern et al., 2000; McLaughlin, 2000; National AfterSchool Association, 2006; Yohalem & Pittman, 2006). Over 75% of respondents in the Power of Us survey stated they are “very committed” to the youth development field

___________________

4 Public information-gathering session, February 8, 2024.

and 60% have remained in the field since their first job; yet most respondents noted they have had between two and five different jobs in the field over their career (AIR, 2025). So, while youth development practitioners appear dedicated to staying in the field, they are unlikely to stay with the same program or organization long term. Understaffed programs are more likely to have program waiting lists, leaving young people without program access. Furthermore, understaffing can lead to more burnout for existing staff, and high turnover can jeopardize the trust built with participants. Understaffing leads to more focus on recruitment, which takes focus away from improving program quality. As one program leader stated in a public session, “At my previous position, all I did was hire and interview, and it really took away from the other work I was doing—data analysis, growing the program, growing partners, all of that stuff.”5 Hiring can be challenging—job expectations often evolve in part because relying on grant funding can mean meeting new requirements or expectations, which can make it difficult to write accurate job descriptions or adequately describe responsibilities to job applicants.

The following sections offer a glimpse into some of the challenges youth development practitioners face that contribute to attrition or may sway individuals against entering the field.

Visibility, Recognition, and Respect

Youth development practitioners are often an afterthought as educators and mentors in young people’s lives. For many reasons, including credential-ism, status hierarchies, and the cultural reality that in the public imagination, teacher is synonymous with educator, youth development practitioners are often left out of broader educational policy and research discourse (Baldridge, 2018; Pozzoboni & Kirshner, 2016). Even though families, school-based professionals, and young people rely on the capabilities, talents, and supervision provided by these professionals and youth-serving organizations, this reliance has not translated into unified public codification, external recognition, or consistent structural support for the youth development workforce. Over the past three decades, national and local efforts to elevate the status of this workforce have increased through standards, certification processes, and national advocacy; however, youth development practitioners continue to experience challenges regarding visibility, recognition, and respect (Baldridge, 2019; Borden et al., 2020; Fusco, 2018; Hirsch, 2005). For example, practitioners recently described how they were called on as essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic to take on the work of facilitating community hubs and online learning—this put them in a vulnerable position without an

___________________

5 Heard in public session panel held by committee on February 8, 2024.

increase in benefits and compensation (Baldridge et al., 2024). In Vasudevan’s (2019) study of career “persisters,” some youth development practitioners shared that, despite their sense of personal fulfillment from their job, they experienced stigmatization among friends and families in their chosen career path, and they observed financial devaluation within larger community organizations that provide services for both adults and young people.

Historically, in the United States, the work of developing relationships, organizing local civic activities, engaging in service, and providing care for children has often been the responsibility of women and people from racially marginalized populations (Daniels, 1987; Hochschild, 2003). In this paradigm, scholars have argued that service-oriented professions, such as social work and nursing, become codified as “semi-professions” when compared with fields such as law and medicine (Abbot & Meerabeau, 1998; Mehta, 2013). What is more, youth development and health care practitioners within the nonprofit structure face what Sarah Jaffe (2021) calls a “labor of love ideology,” in which the nobility of these professions is praised—but not necessarily rewarded—by the larger society.

Compensation

Nearly 20 years ago, researchers and advocates conducted national and local surveys to identify critical needs and challenges faced by the youth development workforce, identifying depressed wages and inadequate benefits as commons issues (Halpern et al., 2000; McLaughlin, 2000; National AfterSchool Association, 2006; Yohalem & Pittman, 2006). These issues appear to persist today. Most respondents (69%) of the Power of Us survey identified better pay and/or benefits as a needed job improvement. This sentiment was more common among respondents aged 18–25, most of whom receive an hourly wage, not an annual salary, which they reported at less than $20 per hour. For comparison, full-time teachers earn about $30 per hour on average (AIR, 2025).

This common experience of low wages combined with demanding work, including long hours that often extend into evenings and weekends, creates a significant challenge in terms of retaining and stabilizing the workforce. Lower-paid employees are more likely to seek new job opportunities compared with those with higher salaries. In its findings from a workforce survey, the National AfterSchool Association (2006) reports bifurcation—a “tale of two workforces”—with full-time program directors and managers expressing more stability and support and higher compensation rates than part-time, direct-service staff.

However, results from the Power of Us survey suggest promising progress in perceptions around wages in the youth development workforce (AIR, 2025). Three out of five (about 60%) respondents (combining leadership

and nonleadership practitioners) suggested that that they are paid a fair amount for the work they do; of those in nonleadership positions, 58% indicated they are paid fairly.

The results from the Power of Us survey aside, average wages for youth development practitioners remain low relative to the cost of living, especially for younger entrants into the field. When asked what they would change about their jobs, respondents cited better pay and benefits (AIR, 2025), followed by less stress (discussed in the following section).

Many youth development practitioners face financial predicaments when entering this workforce (e.g., student loan debt), and they often employ individual coping strategies to persist in the field (Baldridge, 2020a; Vasudevan, 2019), such as taking on additional jobs, relying on family finances, and renegotiating work boundaries at the individual level; however, these individual choices often come at a personal cost, such as prolonging educational advancement and repayment of debt, pay reductions, and adapting life planning (Vasudevan, 2019). Vasudevan (2019) reports that practitioners cite gentrification, housing affordability, and student loans as creating additional barriers to their ability to continue in the field. In a study of Black youth development practitioners, Baldridge (2020b) documents food insecurity, housing instability, and homelessness among respondents.

Job Stress

The blurring of personal and professional boundaries is both a testament to the enthusiastic commitment of youth development practitioners and a source of challenge in navigating organizational expectations and the potential for emotional burnout (Bloomer et al., 2021; Vasudevan, 2019). Bloomer et al. (2021) explored the effects of role ambiguity, finding that, although youth workers are often initially offered some core guidance about their responsibilities, their duties expand over time:

I really would like to know what my job role is. I feel like years ago it used to be to recreate, since I am in recreation, but it seems like in the last 10 years or so, we’re not really recreation anymore. It’s like we’re trying to be everything else, plus recreation. I have to be a social worker, I have to be a janitor. [. . .] I have to go out and weed and blow grass. We have to do the food. It’s just the list goes on and on and on. [. . .] We’ve added it seems like 15 or 20 other titles to the list of what we have to do. (p. 5)

Relatedly, Colvin et al. (2020) identified tensions between public stakeholders’ interpretation and expectations of practitioners’ responsibilities in library and OST settings compared with practitioners’ understanding of their primary obligations and activities in these contexts. Whereas external stakeholders held context-driven, narrow stereotypes of the work in these

settings (e.g., organizing books, providing academic tutoring), practitioners defined and prioritized the relational aspects of their work with children and youth (Colvin et al., 2020).

Although human-serving occupations can be fulfilling, the emotional labor required can result in high stress (e.g., Kim, 2011). OST staff working in programs serving low-income communities may be more likely to work with children and youth facing challenges in their home lives; in a public session, one program leader shared.6

Staff burnout is definitely an issue, and from my experience, it doesn’t have to do with pay or compensation, it has to do with a lot of the trauma that our kids come from. And often afterschool or out-of-school time is the space where they feel safest and have the time to share. Building trusting relationships with youth is probably the most important work that we do all day, every day. And so, we try to give them the opportunity to share that trauma, and they do. And that takes a lot of emotional energy. And I think nobody’s in this for the compensation. [. . .] We do this because we love it. Because we really, really care about the futures and the well-being of these young people. So, there is burnout because it’s not just a 9 to 5. It’s an all day, every day. It’s a part of your soul if you’re doing this work.

Job stress can decrease the use of educator practices that support healthy development, lower the quality of adult–child relationships, and increase burnout and attrition (White et al., 2020). The Power of Us survey found that almost half of respondents (47%) feel burned out at work and that 38% indicated that less stress was a needed improvement in their job (AIR, 2025).

Opportunities for Professional Development

Professional development can help practitioners work more effectively with or on behalf of children and youth (Peter, 2009). The variety in professional development topics mirrors the variation in the youth development field, as programs have different foci that may require specialized professional development (e.g., sports; academic enrichment; science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). Training preferences and perceptions of critical training topics vary among youth workers from different regions, though their overall experiences and perspectives may be similar (Evans et al., 2010).

Professional development in the youth development field consists of workshops; trainings; on-site orientations and mentoring programs; seminars and conferences; local, regional, and statewide networks; online resources; community-driven approaches; and other opportunities focused on improving the

___________________

6 Public information-gathering session, February 8, 2024.

skills of staff who work with children and youth (Bowie & Bronte-Tinkew, 2006; Mahoney et al., 2010; Pheng & Xiong, 2022). Although there are currently no uniform standards for professional development in this field, there is guidance on the quality, competences, and trajectories, as exemplified in statewide afterschool networks (e.g., 2014 Washington State Quality Standards [School’s Out Washington, 2014]) and the National AfterSchool Association’s (2023) core competencies. Professional development options cover a variety of topics, such as youth development issues, activities and program planning, and human resources administration. Box 5-1 offers details on some professional development approaches. With some consensus, researchers have found that high-quality professional development is sustained, coherent, content focused, and based in a community of learners.

Most respondents in the Power of Us survey stated that they participate in trainings, webinars, and conferences for professional learning, and most (84%) have access through their employer (AIR, 2025). These rates were lower for early career respondents and those in part-time or nonleadership positions. Respondents reported lower participation in collaborative professional learning with colleagues or experts, such as professional networking (36%), professional learning communities (25%), coaching (22%), or shadowing (12%). Furthermore, four out of five respondents overall shared that their professional learning met their needs. Yet when asked about improvements to their professional learning opportunities, 34% noted that they want more professional development opportunities, and 40% noted that they wanted more resources such as funding and materials to participate in professional learning (AIR, 2025).

There has also been a growing recognition of the important role young people and community play in building capacity of youth development professionals. Baldridge et al. (2024) found that critical practices for furthering OST capacity-building include healing and restorative activities; intergenerational learning; and liberatory, antiracist practices that lift up lived experiences, honor cultural traditions, and acknowledge sociopolitical contexts (Baldridge et al., 2024; Ginwright & James, 2002; example in Renick et al., 2021).

Organizational Constraints and Culture

Funder expectations to quantify success have placed pressures on program leaders to rapidly increase youth participation numbers and to track metrics such as daily attendance as the primary measure of youth engagement; youth workers have found these expectations to be misaligned with their cultivation of spaces in which youth can attend and participate in programming as needed (Fusco et al., 2013). Although some programs are created to focus on nonacademic areas—such as identity development, sociopolitical development, and critical consciousness–raising—donors can

BOX 5-1

Professional Development Approaches for Youth Development Practitioners

General Training

This approach is the most common among professional development opportunities for youth development practitioners. It consists of workshops on relevant topics at national or regional conferences (usually in the form of one-time sessions lasting 1–2 hours), at out-of-school-time (OST) worksites, and through regional quality improvement initiatives. The goal of these workshops is to provide one-time or short-term training content, often without follow-up support to integrate knowledge into practice. General training approaches can sometimes improve program quality (Fukkink & Lont, 2007), but effects can be limited and short lived (Akiva et al., 2017).

Continuous Improvement

Quality improvement systems drive continuous improvement in youth development practices. Coaching and staff practices include in-service training to build professional knowledge and skills and opportunities for staff participation in decision-making through site-based teams. Quality improvement systems can be as or more effective than general training. However, they involve long lists of standards that can seem overwhelming and impractical in low-resource settings. Such systems tend to operate on top-down assumptions, as external experts developed the measurement tools and system administrators defined quality by these measurements. Youth development practitioners may be involved in improving quality, but not in actively defining what quality should look like in any given setting (Akiva et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2013).

Strengths-Based Support

This approach begins with identifying existing strengths in program or staff practices, rather than the problematic areas. The orientation of training shifts from prescribing best practices to staff to identifying with staff the effective practices already occurring at a site. Then, with facilitation, the staff may begin to consider amplifying or “growing” these practices. Like the continuous improvement approach, the strengths-based approach commits to longer-term, continuous engagement with staff in a facilitative role. Also, the strengths-based approach focuses on supporting quality improvement in local contexts, rather than relying on general prescriptions. Unlike the continuous improvement approach, which relies on comprehensive and often complex definitions and measurements of quality, the strengths-based approach engages and relies on more intuitive assessment and judgment from the staff and site leaders (Akiva et al., 2017).

Professional Learning Communities

Professional learning communities use a practice-focused method to serve as a platform for enhancing the capabilities of youth development practitioners in various educational settings. Typically, a professional learning community engages a cohort of 10–15 professionals in multiple workshops to address a shared goal, such as problem-solving, improving practice, or learning new skills. The goal, along with the length and frequency of the workshops, depends on the

group’s needs. Three components are key to professional learning communities: practice to build skills and confidence; reflection to assess progress and foster accountability; and collaboration to share experiences, solve challenges, and build relationships among participants (Vance et al., 2016).

SOURCE: Generated by the committee, with excerpts from Akiva et al., 2017; Fukkink & Lont, 2007; Smith et al., 2013; and Vance et al., 2016.

instead incentivize focusing only on academics at the expense of these other vital forms of youth development (Baldridge, 2014; Kwon, 2013). These pressures constrain flexibility and creativity in organizations that initially draw and motivate youth development practitioners in this career path (Baldridge, 2019; McLaughlin, 2018; Vasudevan, 2019). Practitioners and program leaders who spend time pushing back on directives from the organization’s board or funder demands, instead of engaging with youth in the way they would like, may simply exit the field.

In addition to the factors mentioned earlier (e.g., financial precarity and familial pressures), in interviews with youth development practitioners, Baldridge et al. (2024) and Vasudevan (2019) found that uneven access to ongoing professional pathways for marginalized populations of youth development practitioners can prompt their exit from direct-service engagement. These practitioners reported encountering barriers to promotion and access to leadership positions, disparities in pay and benefits, and managerial pushouts associated with internal climates of inequities and tokenization (Baldrige et al., 2024). Furthermore, some youth development practitioners cite racism in the workplace, as well as a deficit framing toward youth (e.g., youth needing to be fixed), which counters their belief system and diminishes their motivation to remain in the field (Baldridge, 2019; Wallace Foundation, 2022).

OPPORTUNITIES TO STRENGTHEN THE WORKFORCE TRAJECTORY FOR YOUTH DEVELOPMENT PRACTITIONERS

Each one of our programs have had to find our own ways to survive. And there are different funding streams that do that, but the more stability, the more structures, the more support there is, I think the more that you will see the opportunities for staff to have careers in this space and not just as a stepping-stone in a larger journey.7

___________________

7 Stated by a program director in a public information-gathering session, February 8, 2024.

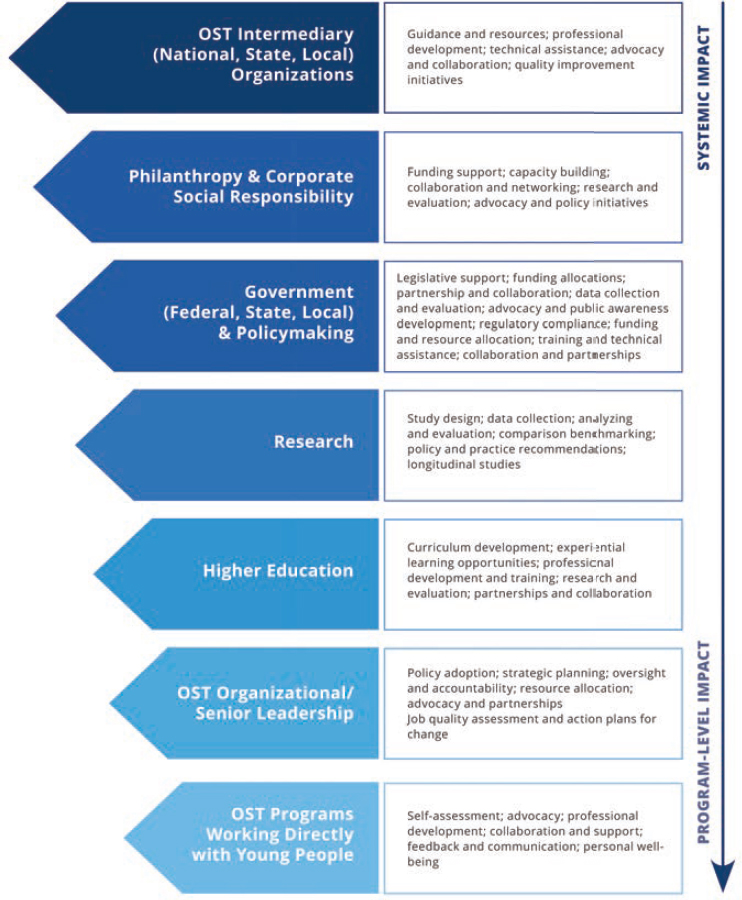

Invest in Job Quality

As stated, the quality of programs is tied to the quality of staff, but more importantly for this chapter’s discussion is understanding that staff quality is impacted by the quality of jobs in the youth development field. The challenges that youth development practitioners face create instability in the OST workforce. To address this instability, the National AfterSchool Association (n.d.), a professional association comprised of 30,000 youth development practitioners serving in OST spaces, released a resource that lays out job quality standards and guidelines for policy advocates and policymakers, government agencies, philanthropic organizations, OST intermediaries, and others (see Figure 5-2). At the core of these standards are fair and livable wages and high-quality working conditions (i.e., safe, inclusive, and supportive environments). Researchers have found that supportive supervisors and a positive work environment can buffer the effects of stress, thereby decreasing burnout (Boyas et al., 2013; Maslach et al., 2001; White et al., 2020). When employees perceive that their supervisors care about their emotional well-being, they are, on average, more motivated and committed to their job (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002).

At its October 2023 public session, the committee heard from OST organizational leaders on the need for employers to commit to creating higher-quality jobs. While this commitment can lead to important program-level impacts, system-level impacts are also possible if funders can incentivize and encourage job quality improvement in the same way they have incentivized improving program quality—by funding elements of job quality directly. For example, the Minnesota Foundation for Women funded “rest grants” for 40 nonprofit women leaders, primarily in youth development, to cultivate rest and well-being (Smith, 2023).

State and federal governments can enhance job quality at the highest levels through legislation and regulations. During and after the pandemic, federal support was provided through the American Rescue Plan and the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Funds Act, which supported OST programs (discussed further in Chapter 8). Some states and cities used these funds to invest in youth workers by helping to provide a living wage.

Other key elements of job quality are training and career development. Regardless of entry, pathway, or organizational requirement, long-term youth development practitioners express a desire for more preparation and knowledge in their work (Peter, 2023). Both private and public institutions have responded to this demand by establishing new training programs and expanding existing ones (Borden et al., 2020). Training can include professional development initiatives, certification, and graduate programs (Silliman et al., 2020).

SOURCE: National AfterSchool Association, n.d.

Some youth development practitioners receive opportunities for professional development through organizational training or intermediary organizations, such as state-level OST networks, that often have relationships with school districts and local governments. When organizations invest in employees through professional development, it signals to employees

that they are valued, which can promote job satisfaction and effectiveness (White et al., 2020). However, staff members are often limited to what their organizations can afford; for staff working with lower-resourced community organizations, accessing educational opportunities can be difficult. Both organizational support and dedicated funding appear key to expanding professional development opportunities for youth development practitioners. National and local intermediaries can also directly provide professional development and even workforce credentials, and/or they can provide information on professional development and supports for workforce pathways (e.g., credentials, postsecondary learning opportunities).

Furthermore, postsecondary learning opportunities can support continuing education for OST staff and open formal pathways to recruit interested individuals. Evans et al. (2010) note low levels of organizational support for continuing education in youth development work. These opportunities are scarce, but undergraduate and master’s programs in youth development show promise in providing multidisciplinary and praxis-oriented approaches to preparing practitioners to enter the field or continue their education in pursuit of career advancement (see Box 5-2). Some higher education institutions extend opportunities to preservice teachers to build their capacity, working together with youth development professionals to build, for instance, equitable practices in the classroom (e.g., Renick et al., 2021). Mahoney et al. (2010) note that a comprehensive approach to professional development would ideally provide both pre- and in-service training for the afterschool workforce; they identify university–community partnerships as a viable path for this training. Vandell and Lao (2016) further detail strategies for workforce engagement in partnership with community organizations and universities.

Providing these support structures not only helps improve young people’s experiences; it also offers an organizational advantage by decreasing staff turnover (Hartje et al., 2008). More comprehensive training opportunities can enhance youth development practitioners’ competencies and OST program quality (Bowie & Bronte-Tinkew, 2006; Peter, 2023; Rhode Island KIDS COUNT, 2003). Staff members who feel competent at their jobs and receive ongoing supervision, support, and professional development trainings are more likely to have intentions of continuing to work in the field, thus increasing staff retention rates (Astroth et al., 2004; Hartje et al., 2008; Hassett, 2022).

Further Data Collection and Research on the OST Workforce

As noted, the Association for Child and Youth Care Practice (n.d.) estimates that there are 2.5 million youth development practitioners in the United States. In 2003, the Annie E. Casey Foundation estimated that

BOX 5-2

Examples of Higher Education Degree and Training Programs

Undergraduate and master’s programs that prepare youth development practitioners may be housed in different departments, including social work, community psychology, education, youth development, sociology, anthropology, and public health (Brion-Meisels et al., 2016).

- The University of California, Irvine Department of Education offers a certificate in afterschool education that combines fieldwork and research. Graduate students work alongside faculty members to conduct research investigating the out-of-school-time (OST) experience, while undergraduates have the chance to work directly in OST and summer programs.

- The City University of New York’s Youth Studies Consortium serves as a clearinghouse to increase capacity for youth studies at the university by developing new courses, certificate and degree programs, web resources, counseling services for students, and faculty research opportunities. Available coursework includes associate, undergraduate, and master’s degrees, as well as certificate programs.

- Rhode Island College offers a bachelor’s degree in youth development through its school of education. This multidisciplinary program combines courses in education, social work, and nonprofit studies to prepare students to work with populations aged 3–21 in a variety of settings. The program includes a student-chosen minor or self-designed concentration composed of five-plus courses, in addition to a 180-hour internship.

- The University of Minnesota offers a youth studies major though its school of social work. The program includes coursework and experiential learning. Students engage community through regular site visits, program observations, community-engaged learning, international exchanges, and internships.

- Clemson University’s Youth Development Leadership Program is a non-thesis master’s degree designed to prepare students for a career addressing the physical, emotional, environmental, and social issues that young people may be facing. The program also partners with a variety of youth-related agencies and organizations to provide learning and work opportunities for students.

- Innovative Digital Education Alliance (IDEA), formerly known as Great Plains Interactive Distance Education Alliance (Great Plains IDEA) and AG IDEA, is a consortium of 20 public universities who provide online education. The consortium has offered a variety of online courses, certificates, and degrees in areas pertaining to agriculture and human sciences to over 11,500 students.

- The University of Louisville’s Social Justice Youth Development Certificate provides youth development professionals in Louisville with training and resources over the course of 30 weeks. The first semester of the program focuses on racial affinity groups as well as racial processing and healing, while the second semester focuses on equity and cultural humility.

there were between two million and four million frontline youth services workers in the United States (Yohalem & Pittman, 2006). These discrepancies reflect the challenge of accounting for the accurate number of youth development practitioners in the country, given the lack of population-level data collection on this workforce. Some efforts are under way to counter this. The Bureau of Labor Statistics oversees the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC),8 a federal statistical standard used by federal agencies to classify workers into occupational categories for the purpose of collecting, calculating, or disseminating data. This system allows for the collection of data on topics such as employment and earnings, skills and education, demographic characteristics, and working conditions. To date, no standard has been applied to youth development practitioners. Thus, the California AfterSchool Network (n.d.) is pursuing such a designation, as a dedicated SOC code would enable the “consistent quantification of the OST workforce, providing essential data on its size, demographics, and trends [. . . it] would streamline partnerships with workforce agencies, fostering collaborative relationships conducive to achieving shared goals” (p. 1). Without this data collection, policymakers, advocates, researchers, and others in the youth development field lack an accurate picture of youth development practitioners on a national scale, which restricts policy-level support for these workers. More research is needed across the spectrum of recruitment and retention, with foci including (1) criteria and best practices for preparing youth development practitioners to enter the field and for continued training and education for those in the field; (2) specific competencies to serve children and youth from low-income and marginalized backgrounds; (3) cost of staff turnover to participants and organizations; and (4) the impact of greater investments in job quality measures, such as wages, benefits, job design, and career advancement.

CONCLUSION

Youth development practitioners are adult leaders who guide children and youth through social, educational, and personal development within informal educational spaces. They are paramount to the success of OST programs. It is widely believed that programs for children and youth are most successful when staff are creative, well trained, skilled at building relationships, and capable of making long-term commitments to programs. Staff must be effective at connecting with young people and understanding their needs, developing and executing interesting activities, interacting with families and other stakeholders in the OST ecosystem, and communicating the mission and policies of the program, among other areas (Bowie & Bronte-Tinkew, 2006).

___________________

8 For more information see https://www.bls.gov/soc/

In practice, there is great variation in the roles of this profession, the responsibilities they take on, and the educational and experiential paths they take to join the field. Youth development practitioners can be executive directors who oversee program administration or instructors who work directly with participants; they may be volunteers or part- or full-time staff. They often fulfill many roles to meet the needs of the program and the young people they serve; a program leader may be serving meals to participants one day and writing grant proposals the next day. Some are school-age youth earning valuable work skills; others are AmeriCorps volunteers or trained youth development specialists with master’s degrees. This heterogeneity has helped the field remain flexible, innovative, and inclusive.

Whether programs focus on violence prevention or arts-based learning, youth development practitioners prioritize building positive, meaningful relationships with young people (Colvin et al., 2020; Hirsch, 2005; Watson, 2012) and are crucial to fostering positive outcomes for youth (Bouffard & Little, 2004; Newman, 2020; see further discussion in Chapters 6 and 7). Finding and retaining high-quality staff is critical to helping participants develop and sustain an interest in OST programs.

Research finds that youth development practitioners are committed to their work and the youth they serve; however, as this chapter reviews, they face challenges around recognition, compensation, job stress, and professional development that can affect their likelihood to enter or stay in the field. These challenges lead to staff turnover, an often-cited problem in the youth development field, as it impacts program availability and quality. Lower staffing levels mean lower organizational capacity and fewer program spots for children and youth, and they require program directors to spend more time on hiring instead of on program development. At the same time, without a federally recognized occupational code and formalized apprenticeship designations, there are no wage protections, which has prompted both public and private funders of OST programs to often (unintentionally) underestimate the needs of staff, from allowable use of dollars for staff compensation, to indirect rate restrictions on talent development and retention.

Based on its findings, the committee offers the following conclusions in support of actionable recommendations (presented in Chapter 9) to improve recognition of this essential workforce and to support its growth and strengthen the career trajectories of its members.

Conclusion 5-1: Youth development practitioners face a number of challenges that can influence retention, such as lack of recognition and respect, low wages, job stress, and limited training and professional development. Addressing the challenges contributing to staff attrition in out-of-school-time programs requires organizational commitment and capacity. Especially for programs serving primarily children and

youth from low-income households that rely on public funding, commitment and capacity often depend on system-level support structures and funding.

Conclusion 5-2: The quality and competency of the workforce supporting out-of-school-time (OST) programs are important elements of program quality, contributing to young people’s level of engagement in programs and the impact of programs on their outcomes. More professional development opportunities through education and training (e.g., through postsecondary degrees, certificates, and organization-led trainings) for individuals interested in or currently serving in youth development can help build the OST workforce pipeline and strengthen career trajectories, which ultimately will strengthen program quality.

Conclusion 5-3: Formalizing national population-level data collection of youth development practitioners can provide a more accurate number and understanding of these staff, which can support policy-level improvements for the out-of-school-time workforce.

REFERENCES

Abbott, P., & Meerabeau, L. (1998). The sociology of the caring professions. University College London Press.

Afterschool Alliance. (2020). America After 3PM: Demand grows, opportunity shrinks. https://afterschoolalliance.org/documents/AA3PM-2020/AA3PM-National-Report.pdf

Akiva, T., Delale-O’Connor, L., & Pittman, K. J. (2023). The promise of building equitable ecosystems for learning. Urban Education, 58(6), 1271–1297.

Akiva, T., Li, J., Martin, K. M., Horner, C. G., & McNamara, A. R. (2017). Simple interactions: Piloting a strengths-based and interaction-based professional development intervention for out-of-school time programs. In Child & Youth Care Forum 46(3), 285–305.

American Institutes for Research (AIR). (2025). The power of us: The youth fields workforce. Findings from the National Power of Us Workforce Survey.

AmeriCorps. (n.d.). AmeriCorps VISTA. https://americorps.gov/serve/americorps/americorps-vista

Anderson, N. S., & Larson, C. L. (2009). “Sinking, like quicksand”: Expanding educational opportunity for young men of color. Educational Administration Quarterly, 45(1), 71–114.

Anderson-Nathe, B. (2008). Contextualizing not-knowing: Terminology and the role of professional identity. Child & Youth Services, 30(1–2), 11–25.

Association for Child and Youth Care Practice. (n.d.). Welcome to ACYCP. https://acycp.org

Astroth, K. A., Garza, P., & Taylor, B. (2004). Getting down to business: Defining competencies for entry-level youth workers. New Directions for Youth Development, 2004(104), 25–37.

Baizerman, M. (1996). Youth work on the street: Community’s moral compact with its young people. Childhood: A Global Journal of Child Research, 3(2), 157–65.

———. (2013). The quest for (higher) professional status: Second thoughts. Child & Youth Services, 34(2), 186–195.

Baldridge, B., Vasudevan, D., Downing, V., Tesfa, E., & Aquiles-Sanchez, P. (In preparation). Toward an expanding typology of youth work settings.

Baldridge, B. J. (2014). Relocating the deficit: Reimagining Black youth in neoliberal times. American Educational Research Journal, 51(3), 440–472.

———. (2018). On educational advocacy and cultural work: Situating community-based youth work[ers] in broader educational discourse. Teachers College Record, 120(2), 1–28.

———. (2019). Reclaiming community: Race and the uncertain future of youth work. Stanford University Press.

———. (2020a). The youthwork paradox: A case for studying the complexity of community-based youth work in education research. Educational Researcher, 49(8), 618–625.

———. (2020b). Negotiating anti-Black racism in ‘liberal’ contexts: The experiences of Black youth workers in community-based educational spaces. Race Ethnicity and Education, 23(6), 747–766.

Baldridge, B. J., DiGiacomo, D. K., Kirshner, B., Mejias, S., & Vasudevan, D. S. (2024). Out-of-school time programs in the United States in an era of racial reckoning: Insights on equity from practitioners, scholars, policy influencers, and young people. Educational Researcher, 53(4), 201–212.

Barford, S. W., & Whelton, W. J. (2010). Understanding burnout in child and youth care workers. Child & Youth Care Forum 39, 271–287.

Blattner, M. C. C., & Franklin, A. J. (2017). Why are OST workers dedicated—or not? Factors that influence commitment to OST care work. Afterschool Matters, 25, 9–17.

Bloomer, R., Brown, A. A., Winters, A. M., & Domiray, A. (2021). “Trying to be everything else”: Examining the challenges experienced by youth development workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 129, 106213.

Borden, L. M., Conn, M., Mull, C. D., & Wilkens, M. (2020). The youth development workforce: The people, the profession, and the possibilities. Journal of Youth Development, 15(1), 1–8.

Borden, L. M., Schlomer, G. L., & Wiggs, C. B. (2011). The evolving role of youth workers. Journal of Youth Development, 6(3), 124–136.

Bouffard, S., & Little, P. (2004). Promoting quality through professional development: A framework for evaluation (Issues and Opportunities in Out-of-School Time Evaluation, No. 8.). Harvard University Harvard Family Research Project.

Bowie, L., & Bronte-Tinkew, J. (2006). The importance of professional development for youth workers (Research-to-results: Practitioner insights No. 2006-17). Child Trends. https://cms.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2006/12/child_trends-2007_06_15_rb_prodevel.pdf

Boyas, J. F., Wind, L. H., & Ruiz, E. (2013). Organizational tenure among child welfare workers, burnout, stress, and intent to leave: Does employment-based social capital make a difference? Children and Youth Services Review, 35(10), 1657–1669.

Bright, G. (2015). The early history of youth work practice. In Youth work histories, policy and contexts (pp. 1–21).

Brion-Meisels, G., Savitz-Romer, M., & Vasudevan, D. S. (2016). Not anyone can do this work: Preparing youth workers in a graduate school of education. In B. Kirshner & K. Pozzoboni (Eds.), The changing landscape of youth work: Theory and practice for an evolving field (pp. 71–90).

California AfterSchool Network. (n.d.). Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) code. https://www.afterschoolnetwork.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/qr_code_can-soc_code_work.pdf?1714070424

Christensen, K. M., & Rubin, R. O. (2020). Exploring competencies in context: Critical considerations for after-school youth program staff. Child & Youth Services, 43(2), 161–186.

Chung, H. L., Jusu, B., Christensen, K., Venescar, P., & Tran, D. A. (2018). Investigating motivation and engagement in an urban afterschool arts and leadership program. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(2), 187–201.

Colvin, S., White, A. M., Akiva, T., & Wardrip, P. S. (2020). What do you think youth workers do? A comparative case study of library and afterschool workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 119.

Community Matters & Breslin, T. (2003). Out-of-School time program standards: A literature review. Rhode Island KIDS COUNT.

Curry, D., Eckles, F., Stuart, C., Schneider-Muñoz, A. J., & Qaqish, B. (2013). National certification for child and youth workers: Does it make a difference? Children and Youth Services Review, 35(11), 1795–1800.

Daniels, A. K. (1987). Invisible work. Social Problems, 34(5), 403–415.

Economic Research Service. (2025). Rural–urban continuum codes—Documentation. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/documentation

Evans, W. P., Sicafuse, L. L., Killian, E. S., Davidson, L. A., & Loesch-Griffin, D. (2010). Youth worker professional development participation, preferences, and agency support. Child & Youth Services, 31(1–2), 35–52.

Fluit, S., Cortés-García, L., & von Soest, T. (2024). Social marginalization: A scoping review of 50 years of research. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–9.

Freeman, J. (2013). The field of child and youth care: Are we there yet? Child & Youth Services, 34(2), 100–111.

Fukkink, R. G., & Lont, A. (2007). Does training matter? A meta-analysis and review of caregiver training studies. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(3), 294–311.

Fusco, D. (Ed.). (2012). Advancing youth work: Current trends, critical questions. Routledge.

———. (2018). Some conceptions of youth and youth work in the United States. In P. Alldred, F. Cullen, K. Edwards, & D. Fusco (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of youth work practice. SAGE Publications.

Fusco, D., Lawrence, A., Matloff-Nieves, S., & Ramos, E. (2013). The accordion effect: Is quality in afterschool getting the squeeze? Journal of Youth Development, 8(2), 14.

Garst, B. A., Weston, K. L., Bowers, E. P., & Quinn, W. H. (2019). Fostering youth leader credibility: Professional, organizational, and community impacts associated with completion of an online master’s degree in youth development leadership. Children and Youth Services Review, 96, 1–9.

Ginwright, S., & James, T. (2002). From assets to agents of change: Social justice, organizing, and youth development. New Directions for Youth Development, 96, 27–46.

Halpern, R. (2002). A different kind of child development institution: The history of afterschool programs for low-income children. Teachers College Record, 104(2), 178–211.

Halpern, R., Barker, G., & Mollard, W. (2003). Making play work: The promise of after-school programs for low-income children. Teachers College Press.

———. (2000). Youth programs as alternative spaces to be: A study of neighborhood youth programs in Chicago’s West Town. Youth & Society, 31(4), 469–506.

Hartje, J., Evans, W., Killian, E., & Brown, R. (2008). Youth worker characteristics and self-reported competency as predictors of intent to continue working with youth. Child Youth Care Form, 37, 27–41.

Hassett, M. P. (2022). The effect of access to training and development opportunities, on rates of work engagement, within the US federal workforce. Public Personnel Management, 51(3), 380–404.

Heathfield, M., & Fusco, D. (2016). Honoring and supporting youth work intellectuals. In K. Pozzoboni & B. Kirshner (Eds.), The changing landscape of youth work: Theory and practice for an evolving field (pp. 127–146). Information Age Publishing.

Hirsch, B. J. (2005). A place to call home: After-school programs for urban youth. Teachers College Press.

Hochschild, J. L. (2003). Social class in public schools. Journal of Social Issues, 59(4), 821–840.

Jaffe, S. (2021). Work won’t love you back: How devotion to our jobs keeps us exploited, exhausted, and alone. Bold Type Books.

Johnston-Goodstar, K., & VeLure Roholt, R. (2013). Unintended consequences of professionalizing youth work: Lessons from teaching and social work. Child & Youth Services, 34(2), 139–155.

Kim, H. (2011). Job conditions, unmet expectations, and burnout in public child welfare workers: How different from other social workers? Children and Youth Services Review, 33(2), 358–367.

Krueger, M. (2002). A further review of the development of the child and youth care profession in the United States. Child and Youth Care Forum, 31(1), 13–26.

Kwon, S. A. (2013). Uncivil youth: Race, activism, and affirmative governmentality. Duke University Press.

Larson, R. W., Walker, K. C., Rusk, N., & Diaz, L. B. (2015). Understanding youth development from the practitioner’s point of view: A call for research on effective practice. Applied Developmental Science, 19(2), 74–86.

Mahoney, J. L., Levine, M. D., & Hinga, B. (2010). The development of after-school program educators through university-community partnerships. Applied Developmental Science, 14(2), 89–105.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422.

Matloff-Nieves, S. (2007). Growing our own: Former participants as staff in afterschool youth development programs. Afterschool Matters, 2007, 15–24.

McLaughlin, M. (2000). Community counts: How youth organizations matter for youth development. Public Education Network.

———. (2018). You can’t be what you can’t see: The power of opportunity to change young lives. Harvard Education Press.

McLaughlin, M., Irby, M., & Langman, J. (1994). Urban sanctuaries: Neighborhood organizations in the lives and future of inner city youth. Jossey-Bass.

Mehta, J. (2013). From bureaucracy to profession: Remaking the educational sector for the twenty-first century. Harvard Educational Review, 83(3), 463–488.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Shaping summertime experiences: Opportunities to promote healthy development and well-being for children and youth. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25546

———. (2024). Promoting learning and development in K-12 out-of-school time settings. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27885

National AfterSchool Association. (n.d.). Out-of-school time job quality standards. https://cdn.ymaws.com/naaweb.org/resource/collection/09323F21-6295-4670-80D5-824790C2B13D/NAA_OST_Job_Quality_Standards_for_Release.pdf

———. (2006). Understanding the afterschool workforce: Opportunities and challenges for an emerging profession. Cornerstones for Kids.

———. (2023). Core knowledge, skills & competencies for out-of-school time professionals. https://cdn.ymaws.com/naaweb.org/resource/collection/F3611BAF-0B62-42F9-9A26-C376BF35104F/NAA_Core_Knowledge_Skills_Competencies_for_OST_Professionals_rev2023.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). Back-to-school statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts

Newman, J. Z. (2020). Supporting the out-of-school time workforce in fostering intentional social and emotional learning. Journal of Youth Development, 15(1), 239–265.

Noam, G., & Bernstein-Yamashiro, B. (2013). Youth development practitioners and their relationships in schools and after-school programs. New Directions for Youth Development, 137, 57–68.

Perry, A. (2019, October 16). For better student outcomes, hire more Black teachers. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/for-better-student-outcomes-hire-more-black-teachers/

Peter, N. (2009). Defining our terms: Professional development in out-of-school time. Afterschool Matters, 9, 34–41.

Pheng, L. M., & Xiong, C. P. (2023). Creating and supporting pathways to sustained careers in youth work. In G. Hall, J. Gallagher, & E. Starr (Eds.), The heartbeat of the youth development field: Professional journeys of growth, connection, and transformation (pp. 17–55).

———. (2022). What is social justice research for Asian Americans? Critical reflections on cross-racial and cross-ethnic coalition building in community-based educational spaces. Educational Studies, 58(3), 337–354.

Pozzoboni, K. M., & Kirshner, B. (Eds.). (2016). The changing landscape of youth work: Theory and practice for an evolving field. Information Age Publishing.

Renick, J., Abad, M. N., van Es., E. A., & Mendoza, E. (2021). “It’s all connected”: Critical bifocality and the liminal practice of youth work. Child & Youth Services, 42(4), 349–373.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698.

Robinson, K., & Akiva, T. (2021). It takes an ecosystem: Understanding the people, places, and possibilities of learning and development across settings. Information Age Publishing.

Ross, L. (2013). Urban youth workers’ use of “personal knowledge” in resolving complex dilemmas of practice. Child & Youth Services, 34(3), 267–289.

Sanchez, B. (2016). Mentoring for Black male youth. National Mentoring Resource Center & Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. https://nationalmentoringresourcecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/BlackMales_Population_Review.pdf

School’s Out Washington. (2014). Quality standard for afterschool & youth development programs. https://schoolsoutwashington.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Quality-Standards-PDF-2-14-14-Final-webwithnewlogo.pdf

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15, 4–14.

Silliman, B., Edwards, H. C., & Johnson, J. C. (2020). Long-term effects of youth work internship: The Project Youth Extension Service approach. Children and Youth Services Review, 119, 105436.

Singh, M. V. (2021). Resisting the neoliberal role model: Latino male mentors’ perspectives on the intersectional politics of role modeling. American Educational Research Journal, 58(2), 283–314.

Smith, C., Akiva, T., Sugar, S., Devaney, T., Lo, Y. J., Frank, K., Peck, S. C., & Cortina, K. S. (2013). Continuous quality improvement in afterschool settings: Impact findings from the Youth Program Quality Intervention study. Forum for Youth Investment.

Smith, K. (2023, September 25). $10K grants to help 40 female nonprofit leaders combat burnout, courtesy of Women’s Foundation. The Minnesota Star Tribune. https://www.startribune.com/womens-foundation-of-minnesota-grants-female-leaders-rest-wellness-burnout-nonprofit-philanthropy/600307416

Starr, A. (2003). ‘It’s got to be us’: Urban youthworkers. Children & Youth Services Review, 25(11), 911–933.

Starr, E., Franklin, E., Franks, A., Hall, G., McGuiness-Carmichael, P., Parchia, P., KarmelicPavlov, V. A., & Walker, K. (2023). Youth fields workforce perspectives. Afterschool Matters, 37, 7–45.

Travis, R., Jr. (2010). What they think: Attributions made by youth workers about youth circumstances and the implications for service-delivery in out-of-school time programs. Child & Youth Care Forum, 39(6), 443–464.

Van Steenis, E. J. (2020). Toward a valued career: A multisite study of youth workers in different stages of the profession [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Colorado at Boulder.

Vance, F. (2012). An emerging model of knowledge for youth development professionals. Journal of Youth Development, 7(1), 36–55.

Vance, F., & Goldberg, R. (2020). Creating a rising tide: Improving social and emotional learning across California. Journal of Youth Development, 15(1), 165–179.

Vance, F., Salvaterra, E., Michelsen, J. A., & Newhouse, C. (2016). Getting the right fit: Designing a professional learning community for out-of-school time. Afterschool Matters, 24, 21–32.

Vandell, D., & Lao, J. (2016). Building and retaining high quality professional staff for extended education programs. International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 4(1), 52–64.

Vasudevan, D. S. (2017). The occupational culture and identity of youth workers: A review of the literature [Qualifying paper]. Harvard University.

———. (2019). “Because we care”: Youth worker identity and persistence in precarious work [Doctoral dissertation]. Harvard University.