Practices for Controlling Tunnel Leaks (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

The 2022 National Tunnel Inventory lists 552 tunnels, and this number has increased each year since the implementation of the National Tunnel Inspection Standards (NTIS). In addition to the tunnels in their inventories, many states also have cut-and-cover tunnel structures (which support air rights developments such as parks or buildings) that may not be included in the 552 tunnels, and many more cut-and-cover structures are planned across the country. When tunnels and underground structures leak, the investigation and design to control the infiltration and the repairs to the tunnel and its systems caused by the leakage result in significant expense. The remediation of water infiltration is expensive, so effective methods to reduce or control infiltration for the long term are needed.

Background

Water infiltration is a common problem in tunnels and, if left unchecked, accelerates the deterioration of a structure and its functional system elements. In highway tunnels, structural deterioration caused by water infiltration is indicated by corrosion, delamination, spalling, loose and missing tiles, and efflorescence and dripping. The operation of tunnel functional systems such as lane signals, signs, ventilation fans, conduits, and lighting may be affected, as well as their anchorages and supports. In low-temperature climates, water infiltration results in icicles overhead, ice formation on walls, and slippery roadways, all of which are hazards for the traveling public. Controlling water infiltration is a challenge to tunnel owners. Solutions that last for many years are needed. Although various methods exist to reduce or control infiltration, understanding the best methods and materials to use in certain situations will improve the success of the remediation.

Before repairing a structure that has deteriorated because of water infiltration, staff need to investigate and determine the source and location of the leak, and to mitigate the water to prevent deterioration reoccurring. Shallow cut-and-cover tunnels and tunnels constructed in urban areas may have utilities above the tunnel that are a potential source of infiltration. This is a special case and requires investigation and testing to confirm if a utility is the source. Other potential sources of water infiltration are surface runoff and groundwater. Because tunnels are constructed with joints to accommodate movement (to prevent cracking), tunnels have numerous joints and these locations are common avenues for water infiltration. Investigating construction details of joints and waterproofing (if any was installed) are helpful in understanding how the leakage is occurring and in formulating mitigation strategies.

Tunnel leaks are typically mitigated from the inside of the tunnel (negative side) because the outside of the tunnel is buried and inaccessible. Where it is possible to repair waterproofing from the outside (positive side) by excavating and making repairs, this approach may be taken. Methods used to mitigate infiltration from the inside are varied and include but are not limited

to redirecting the water; injecting grouts into cracks, joints, and gaskets; replacing joint seals; grouting behind the liner; applying coatings to the inside of the liner; and creating wells. Selection of these methods will reflect the degree of infiltration, the subgrade conditions, and other factors. Remediation is typically consistent with the design strategy for the tunnel to avoid putting unintended hydrostatic loads on the liner if the liner was not designed for that condition.

Objectives

The objective of this synthesis is to document the experience of state DOTs in controlling and mitigating leakage in their highway tunnels. The specific areas addressed in the synthesis are (1) problems caused by leakage; (2) the methods used to investigate, detect, and identify the source of water infiltration; and (3) the mitigation methods used by state DOTs and method effectiveness over time. The synthesis study attempts to capture the extent of leakage in existing air rights structures that may not be included in the state tunnel inventory, given that these are effectively cut-and-cover tunnel structures, to the extent this information is known by the state DOT tunnel managers. In addition, the synthesis also documents if acceptance criteria are used by state DOT tunnel owners on new tunnel construction and rehabilitation projects and the specifics of any such acceptance criteria.

Approach

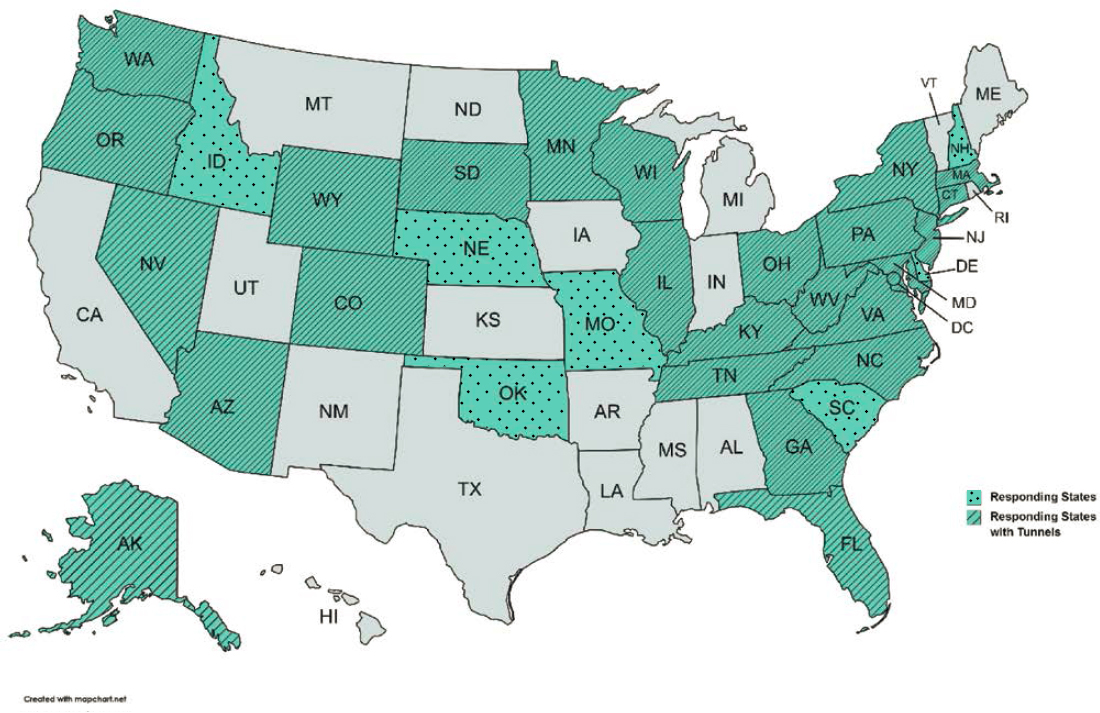

The first task of the synthesis was development of a survey to obtain information from state DOT tunnel managers about their experiences with tunnel water infiltration and remediation methods. The survey was distributed to the tunnel inspection managers of 50 state DOTs, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico (52 total). For agencies with no tunnels, the survey was sent to the bridge inspection manager. A total of 33 DOTs responded (63%), which included DOTs with no tunnels. Of the 33 DOTs that responded, 26 DOTs responded they own tunnels. Out of that group of 26, 21 stated that they had tunnels and tunnel-type structures (i.e., long decks over the roadway) with water infiltration in the past 10 years. Of the responding DOTs with water infiltration experience, follow-up interviews were held with four tunnel owners to discuss this topic in more detail. The responding DOTs and those with tunnels are shown in Figure 1.

The survey responses and case examples are limited to the experience of DOTs. Recognizing that many of the tunnels in the National Tunnel Inventory (NTI) are owned, operated, and maintained by municipalities, other state agencies, or private owners, the synthesis attempted to capture the prevalence of tunnel leaks in those tunnels and the experience of the other tunnel owners in controlling leaks, when the state DOT was aware of them. The information provided was solely from the DOTs through the survey responses and case example interviews.

The survey and interviews examined state DOTs’ experiences with controlling water infiltration in their tunnels, including the methods for detecting and identifying sources of leaks, mitigation methods and acceptance criteria for remediation projects. The results of the survey are documented in Chapter 3, while the results of the agency interviews are provided in Chapter 4.

While awaiting survey responses, the synthesis authors began a literature search to investigate the current body of knowledge about water infiltration mitigation methods and their effectiveness. The literature search investigated (1) the relationship between tunnel construction method and water infiltration, (2) successful remediation methods, and (3) industry use of acceptance criteria for rehabilitation projects focused on mitigating water infiltration. The results of the survey, the literature search, and the case examples provided by four DOTs are summarized in this report, along with a summary of the findings and possible future research on mitigation measures for water infiltration.

Terms

Terms used in the survey and synthesis report are presented here.

- Curtain Grouting—a technique where holes are drilled through the tunnel liner and chemical grout is pumped behind the liner at high pressure to prevent water permeating from directly behind and through the liner.

- Cut-and-Cover Tunnel—this type of tunnel construction involves excavating from the ground surface down, constructing a box structure, and then backfilling to cover the tunnel. Cut-and-cover tunnels are often rectangular but may be other shapes as well.

- Deck-over Structure—an enclosed roadway formed by a deck constructed over a depressed roadway, often supporting a plaza, park, buildings or other facilities. May also be referred to as “plazas,” “lids,” or “air rights structures.”

- Drill-and-Blast Tunnel—a tunnel excavated by drilling into the rock subgrade and blasting to facilitate removal of subgrade for installation of the tunnel liner. Drill-and-blast tunnels are often horseshoe shaped.

- GPR—a geophysical probing of the liner and substrate using radar pulses to identify voids and irregularities.

- Immersed Tube Tunnel—a tunnel constructed and then floated into position in a body of water, then sunk into final position. Immersed tube tunnels are often rectangular but may be other shapes.

- Jacked Tunnel—often used to cross under a roadway or railway, a jacked tunnel advances a tunnel liner hydraulically through the ground. Jacked tunnels are typically rectangular but may be circular or oval.

- LiDAR—a method of obtaining a three-dimensional (3D) representation of a surface using a laser and measuring the time for reflected light to return to the receiver.

- Photogrammetry—a high-resolution photography method used to obtain physical information, used as an aid in assessing the conditions of structures. By overlapping two-dimensional (2D) photographs, a 3D model can be created.

- Sequential Excavation Method (SEM) Tunnel—a tunnel excavated sequentially in cross section, mining a portion of a ring at a time and reinforcing the exposed ground with shotcrete, until a complete ring is completed. An SEM tunnel is typically oval or circular in shape.

- Shield-Driven/Bored Tunnel—a tunnel constructed using a tunnel shield/tunnel boring machine (TBM) to excavate the ground for installation of the tunnel liner. Bored tunnels are typically circular in shape.

- Substrate—the material or ground conditions behind the tunnel liner.

- Thermography—also called thermal imaging, this method is used to evaluate temperature fluctuations to aid in identifying otherwise undetectable issues, such as the flow of water behind a tunnel liner.

- Tunnel—the NTIS defines a tunnel as an enclosed roadway for motor vehicle traffic with vehicle access limited to portals, regardless of type of structure or method of construction, that requires, based on the owner’s determination, special design considerations that may include lighting, ventilation, and fire protection systems.

- Tunnel-Type Structure—the tunnel definition provided in NTIS and provided earlier is expanded to include enclosed roadways longer than 300 ft.; this may include elongated decks extended across roadways (see Deck-over Structure earlier in this list) and other lengthy structures that may or may not be included in a DOT’s tunnel inventory. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 502 standard provides recommendations (and is the code in some states) for fire and life safety systems for tunnels and limited access roadways beginning at a length of approximately 300 ft.

- Umbrella Waterproofing—a waterproofing system that allows water through the structure and then directs it to an internal drainage system.

Organization

The remainder of this report is organized as follows:

- Chapter 2, Literature Review, presents relevant published information, from both domestic and international sources, including presentations made at and papers published for various conferences.

- Chapter 3, State of the Practice, describes the questions asked in the survey and summarizes the state DOT responses. The chapter investigates the experience of DOTs with water infiltration and methods used to remediate leakage.

- Chapter 4, Case Examples, presents a summary of the four agency interviews.

- Chapter 5, Summary of Findings, summarizes the key findings of the synthesis and identifies information gaps and potential areas for further research.

- Appendix A is a copy of the survey.

- Appendix B provides the aggregate survey results.

- Appendix C lists the case example interview questions.