Intermodal Passenger Facility Planning and Decision-Making for Seamless Travel (2024)

Chapter: 8 Funding and Financing

CHAPTER 8

Funding and Financing

Introduction

Intermodal passenger facility projects are often costly and complex undertakings requiring substantial financial resources. Project owners typically work with multiple entities to explore all possible sources of funding, financing options, and partnerships to complete and maintain facility projects.

This chapter discusses ways to choose the right funding program and financing approach and summarizes the funding, financing, and innovative delivery options available. Appendix D provides detailed information on funding sources available as of this report’s publication. Appendix E is a case study of Denver Union Station’s innovative financing and project delivery approach.

For the purposes of this report, funding is considered to be any resource available directly from federal, state, or local public entities to pay for an intermodal passenger facility’s up-front capital costs and ongoing operating costs, including funds that may be required to pay debt service. Financing represents borrowing (and other strategies) to pay for project capital costs over time.

Choosing the Right Funding Program/Approach

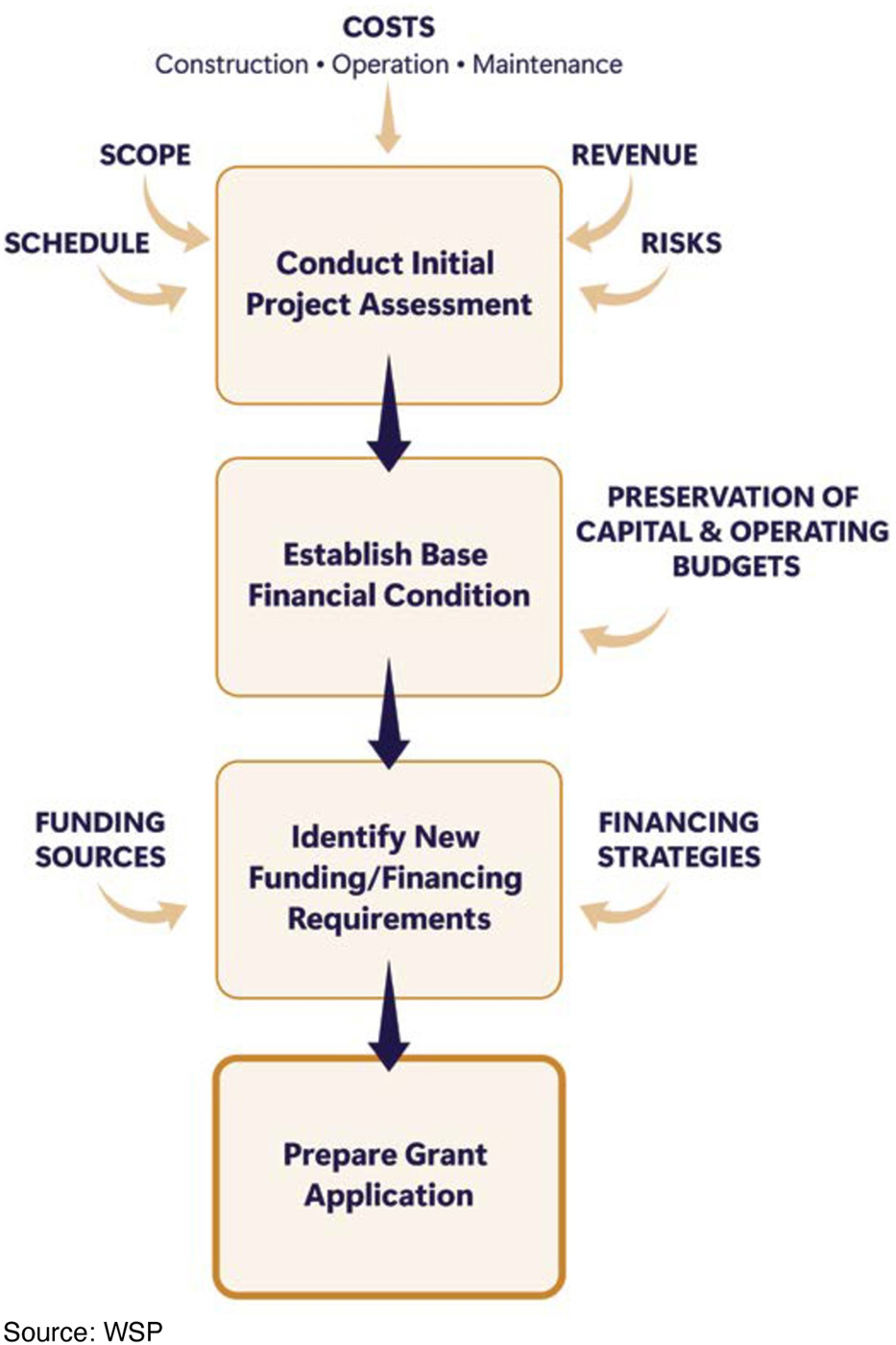

The process of choosing among funding programs and financing approaches is illustrated in Figure 11 and includes the following elements, each described further in this chapter.

- Conducting the initial project assessment.

- Establishing the base financial condition.

- Identifying new funding and financing requirements.

- Preparing the grant application.

Conduct Initial Project Assessment

Intermodal facility project owners should initially assess the project scope, completion schedule, and costs for constructing, operating, and maintaining the facility. This step also includes determining whether the project will produce revenue and identifying potential risks.

Establish Base Financial Condition

Once an intermodal passenger facility owner understands the associated costs and risks, the next step for the owner is to know the project’s baseline financial condition, including the

potential use of existing funding. This analysis must take into consideration how much existing funding can be used without harming the entity’s future financial outlook, capital improvement plans, and operating budgets. The amount of the project that the owner cannot fund is the funding gap.

Identify New Funding and Financing Requirements

Owners are advised to consider all available federal funding and innovative financing opportunities that are available and most align with the project’s needs. When considering grant funding opportunities, applicants should note the minimum and maximum award requirements, whether there is a required match, and what type of project activities are allowed. For financing opportunities, owners should consider the terms of the agreement, including the interest rate, the principal available, and the length of repayment. The owner can then prioritize opportunities based on what aligns best with the project.

Understand Prior Funding Restrictions

Owners of existing facilities are advised to consult funding agreements when renovating a facility constructed with government funds.

Prepare the Grant Application

For each prioritized grant program, owners should develop a timeline for the application development. Owners are encouraged to review prior notices of funding opportunities (NOFOs), including timing of notices and decisions to establish expected time frames for application and award. The timeline should list potential grant programs and their expected timing. In addition, owners should review the NOFOs to identify elements that will make the project’s story compelling, and should use data and analysis to convey the story. Most grants are awarded to projects that are close to being shovel ready, so advancing design, securing environmental clearances, obtaining required permits, and documenting local funding commitments and regional support will all help to make a more compelling and competitive case for a grant award.

Federal Funding Strategies

There are numerous federal funding and financing strategies applicable to the development of new and expanded/renovated intermodal passenger facilities. The following discussion describes funding sources and financing options as of this report’s publication. Most of the funding is authorized through federal fiscal year (FFY) 2026. Reauthorization or new legislation is needed to continue these programs. Several of the funding programs have been in effect for decades and can be expected to be continued.

While financing intermodal passenger facility projects can help pay for up-front capital costs, this approach typically costs more in terms of future debt serviced on the borrowed funds. Financing also typically requires a dedicated local repayment source. The passage of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law also made financing programs more attractive and accessible for local municipalities.

Federal funding programs include discretionary grant opportunities and formula programs administered by U.S. DOT and its modal administrations, including FHWA, FTA, FRA, the Maritime Administration, and FAA. General formula and grant programs apply to the following four categories of funding:

- Multimodal transportation projects,

- Vehicle funding programs,

- Roadway funding programs, and

- Funding for airports, marine ports, and railroads.

Many of the federal funding programs provide resources for multiple types of capital expenditures, including for vehicles and facilities. Appendix D describes each program and includes detailed tables of matching requirements, eligibility, funding amounts through FY 2026, and typical award size. Readers are also encouraged to consult the U.S. DOT website (https://www.transportation.gov/grants) for current information on grant programs.

General Formula and Grant Programs

General formula and grant programs provide funding for a range of multimodal transportation projects and provide the greatest range of eligible activities. (See Table 10.) Seven of these nine general programs can be used to fund planning, design, or construction. The general programs are split between four formula programs and five discretionary grant programs.

Federal Vehicle Funding Programs

The vehicle funding programs provide formula and discretionary grant funds for transit vehicle acquisition, including ZEV fleets, supporting facilities such as EV charging infrastructure, and ferries. (See Table 11.)

Table 10. Federal general formulas and grants.

| Program | Type |

|---|---|

| FHWA Carbon Reduction Program | Formula |

| FHWA Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement (CMAQ) | Formula |

| FHWA Surface Transportation | Formula |

| FTA Sections 5303, 5304, and 5305 | Formula |

| FTA Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) Planning Program | Grant |

| U.S. DOT National Infrastructure Project Assistance (MEGA) | Grant |

| U.S. DOT Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) | Grant |

| U.S. DOT Rural Surface Transportation | Grant |

| U.S. DOT Strengthening Mobility and Revolutionizing Transportation (SMART) | Grant |

See Appendix D for matching requirements, eligibility, current funding amounts, and typical award size.

Table 11. Federal vehicle funding programs.

| Program | Type |

|---|---|

| FHWA Charging and Fueling Infrastructure (CFI) Discretionary Grant Program | Grant |

| FHWA National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Formula Program | Formula |

| FTA Ferry Programs | Grant |

| FTA Section 5339 (a), (b), and (c) | Formula/grant |

See Appendix D for matching requirements, eligibility, current funding amounts, and typical award size.

Federal Roadway Funding Programs

Roadway programs support the development of bicycle, pedestrian, and road infrastructure and can be used to support such infrastructure at intermodal passenger facilities. (See Table 12.)

Federal Funding for Rail, Aviation, Maritime, and Transit Stations

Table 13 shows funding options for passenger rail, rail infrastructure and safety, airports, ports, and rail stations.

Financing Options and Innovative Delivery Strategies

Ideally, maximizing funding from the many sources described in this chapter would cover the entire public cost of delivering a project. If there is a funding gap after all possible public funding sources have been exhausted, the remaining capital cost shortfall is generally assumed

Table 12. Federal roadway funding programs.

| Program | Type |

|---|---|

| FHWA Advanced Transportation Technologies and Innovation (ATTAIN) Program | Grant |

| FHWA Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) | Formula |

| U.S. DOT Nationally Significant Multimodal Freight and Highway (INFRA) Program | Grant |

| U.S. DOT Neighborhood Access and Equity (NAE) Grant Program | Grant |

| U.S. DOT Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program | Grant |

| U.S. DOT Safe Streets and Roads for All (SS4A) Grant Program | Grant |

See Appendix D for matching requirements, eligibility, current funding amounts, and typical award size.

Table 13. Federal funding for airports, ports, and railroads.

| Program | Type |

|---|---|

| FAA Airport Improvement Program (AIP) | Formula/grant |

| FAA Airport Terminal Program (ATP) | Grant |

| FAA Passenger Facility Charge (PFC) Local User Fee | Fee |

| FRA Consolidated Rail Infrastructure and Safety Improvements (CRISI) Program | Grant |

| FRA Federal-State Partnership for Intercity Passenger Rail Grant Program | Grant |

| FTA All Stations Accessibility Program (ASAP) | Grant |

| U.S. DOT Port Infrastructure Development Program (PIDP) | Grant |

See Appendix D for matching requirements, eligibility, current funding amounts, and typical award size.

to be covered by some form of public financing or an alternative revenue source. If a funding gap is large, and available debt financing terms are less favorable or flexible, future revenue streams from the project may not be sufficient to cover the resulting debt, and the project will not be financially feasible. Maximizing funding from all possible federal, state, and local sources can minimize the funding shortfall and the resulting debt issuance required.

The following section describes some common debt financing mechanisms available at the federal level (and state/local level, depending on the location) as well as innovative, project-specific mechanisms that may be available for consideration for intermodal passenger facilities.

For intermodal passenger facility projects, these additional, project-specific mechanisms generally leverage two primary opportunities that these projects tend to catalyze: (1) land use/future development potential, and (2) mobility-focused revenue-generation potential. In each case, successfully generating revenue from land use and mobility opportunities requires significant planning and time to develop and structure partnerships with the necessary public- and private-sector stakeholders. Such opportunities also have implications for the types of governance structures that may be most applicable, depending on the given scenario.

Federal Financing Options

The two main federal financing options for intermodal passenger facility projects are commonly known as TIFIA and RRIF (see the following two subsections).

Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act and TIFIA 49

The Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) provides low-cost financing to fill funding gaps in infrastructure projects. TIFIA credit assistance is available as direct loans, loan guarantees, and standby lines of credit to finance surface transportation projects of national and regional significance (U.S. Department of Transportation 2024a). Credit assistance has historically been capped at 33% of reasonably anticipated eligible project costs. However, in 2022, the U.S. DOT introduced the TIFIA 49 initiative, which increased the maximum loan amount from 33% to 49% of project costs for eligible transit and TOD projects. In addition to this increase, the IIJA has made TIFIA credit assistance more attainable and flexible by (1) relaxing requirements for investment-grade ratings, and (2) increasing the maximum loan duration from 35 years to 75 years for projects with an estimated life greater than 50 years (U.S. Department of Transportation 2024a).

TIFIA loan eligibility was also expanded to include port, TOD, and airport terminal and airside projects. To be eligible, these types of projects must be added to State Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) project lists under special exceptions (U.S. Department of Transportation 2024a).

Miami Intermodal Center Use of TIFIA

Miami Intermodal Center blended multiple federal, state, and local funding sources to fund a $2 billion project to improve ground travel to and within Miami International Airport. As part of these sources, the project secured a $270 million loan from TIFIA and $6 million in federal grants. See https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/project_profiles/fl_miami_intermodal.aspx for more information.

Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing

The Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) program provides federal credit assistance in the form of direct loans, loan guarantees, and lines of credit to finance rail projects. RRIF offers direct loans for up to 100% of the project cost (or up to 75% for eligible TOD projects). The program allows a repayment period of up to 75 years after the date of substantial completion of the project, pursuant to the IIJA. The RRIF program is authorized to provide up to $35 billion in direct loans and loan guarantees to finance development of railroad infrastructure, with $7 billion reserved for freight railroads other than Class I carriers (railroads with operating revenue of less than $272.0 million annually). In addition, the IIJA, subject to appropriations, added discretionary credit assistance of $50 million per year up to $20 million per loan. At least 50% of such credit assistance is set aside for freight railroads other than Class I carriers. Furthermore, the IIJA made TOD a permanent project eligibility. Lastly, the infrastructure law codified the RRIF express program, which establishes an expedited credit review process for loans that meet certain financial and operational criteria and requires regular updates from U.S. DOT on status of application so as to reduce applicant uncertainty (U.S. Department of Transportation 2024a).

Eligible applicants for RRIF financing include railroads, state and local governments, government-sponsored authorities and corporations, limited-option freight shippers that intend to construct a new rail connection, and joint ventures that include at least one of the preceding categories. The FRA notes that RRIF financing may be used to:

- Acquire, improve, or rehabilitate intermodal or rail equipment or facilities, including track, components of track, bridges, yards, buildings and shops, and the installation of positive train control systems;

- Develop or establish new intermodal or railroad facilities;

- Reimburse planning and design expenses relating to these activities;

- Refinance outstanding debt incurred for the purposes listed previously; and

- Finance TOD (U.S. Department of Transportation 2024a).

Other Financing Options

Additional intermodal passenger facility financing options include:

- User fees,

- Dedicated taxes,

- Tax-exempt municipal bonds,

- State infrastructure bank loans,

- Private activity bonds,

- P3 financing, and

- Value capture (U.S. Department of Transportation 2024a).

User Fees

User fees are a common funding source for financing construction, operations, and maintenance. Bonds backed by future user fee revenues help fund capital costs. The fees can be direct (facility users) or indirect tolls or fees. Entities implementing user fees must decide how to collect them and when to adjust rates in the future. One risk from this method is that it can be difficult to raise future rates to keep up with increasing maintenance costs (Dornan and March 2005).

Dedicated Taxes

Dedicated taxes can be levied to support intermodal passenger facility construction, operations, and maintenance. As with user fees, bonds can be issued backed by future tax revenues. Dedicated taxes may be local or state taxes, usage taxes (e.g., for rental cars or lodging), or license-based taxes such as on ridehailing companies. Enacting taxes or fees to support an intermodal passenger facility project is often a potentially lengthy and politically challenging process.

Tax-Exempt Municipal Bonds

Tax-exempt municipal bonds are the most common debt instrument used by state or local governments to finance infrastructure projects. Government agencies and eligible nonprofit entities may directly issue bonds that are exempt from federal taxes, which reduces interest rates and financing costs. Issuers are also often exempt from state and local taxes, further reducing interest rates and financing costs. Laws in some states permit both state and local funding partners to use tax-exempt bonds to fund the state and local share of project costs. In other states, limitations on bonding capacity or insufficient revenues preclude this option.

State Infrastructure Bank Loans

State infrastructure bank (SIB) loans are revolving loan programs funded with seed money from the federal or state government. SIB programs provide loans or loan guarantees that are repaid with project revenues or pledged funding from state or local sources. The repayment terms are often very flexible, often allowing for deferral of principal payments. Program availability and specific loan terms vary by state but, if available, can be a complementary source of financing combined with other sources such as TIFIA loans.

Private Activity Bonds

Private activity bonds (PABs) are tax-exempt securities issued by public entities to finance privately developed infrastructure that benefits the public. PABs offer lower financing costs when compared to taxable debt. The private sector is responsible for paying the PABs back and assumes all financial risk. PABs require private-sector interest and a public entity to serve as a conduit. Like SIB loans, program availability, debt issuance terms, and project eligibility can vary by state. At the federal level, PAB eligibility automatically includes any project that is eligible for TIFIA credit assistance, which includes multimodal facilities (U.S. Department of Transportation 2024a).

P3 Financing

The two most typical types of P3 financing are P3 equity and P3 debt. P3 equity represents a private ownership stake in an enterprise with an aim of making a profitable return and may include investment from commercial developers, financial investors, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, insurance companies, and private equity funds. A P3 equity stake is just one component of an overall project delivery strategy. P3 debt can be coupled with equity to finance the initial investment and may include PABs, taxable bonds, bank loans, and other debt instruments. P3s have the potential to support a significant share of project costs and could facilitate lower project costs as part of a comprehensive program delivery strategy. However, the resulting transfer of project risk to the private sector typically requires that program sponsors also transfer some direct control of the program (U.S. Department of Transportation 2024a).

Value Capture

P3 and TIFIA Financing: Salesforce Transit Center

Salesforce Transit Center in San Francisco, CA, relied on local, regional, state, federal, and private funding to assist with the funding of the project. This included a $171 million TIFIA loan and over $400 million in federal grant funds, and a $154 million bridge loan from a private entity. See https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/project_profiles/ca_transbay_transit.aspx for more information.

Value capture is the concept of capturing the enhanced real estate value attributable to a public improvement (such as transit or other TOD-supportive infrastructure) to help fund that improvement. Value capture can be categorized as joint development and a family of methods known as district value capture, which includes tax increment financing and special assessment districts (Raine et al. 2021).

Joint Development

Depending on the type of real estate transaction structure involved, the public revenue from joint development can be generated in a variety of ways. In cases where the public landowner wishes to maintain ownership of the property in the future, it can participate in the development as a partner, collecting an agreed upon share of future development revenue. Other transactions that require less ongoing involvement by the public entity include long-term ground leases and long-term air-rights leases. The terms of such leases can be negotiated to include a steady stream of annual payments; a large, one-time, up-front payment; or some combination depending on what works best for all parties involved. Other models include collecting proceeds from the outright sale of excess land and from collecting rents of on-site space from commercial tenants. TCRP Report 224: Guide to Joint Development for Public Transportation Agencies (Raine et al. 2021) provides extensive information on this topic.

District Value Capture

Tax Increment Financing

In general terms, tax increment financing (TIF) is a mechanism for capturing all or part of the increased property tax paid by properties within a designated area. TIF is not an additional

tax, nor does it deprive governments of existing property tax revenues up to a set base within the TIF district. Instead, part of or all future property taxes (above the set base level) resulting from increased property values or from new development are dedicated to paying for the public improvement that caused the value increases and additional development (Federal Highway Administration Center for Innovative Finance Support, n.d.-a).

Special Assessment Districts

Special tax assessments are additional taxes paid within defined geographic areas or districts where landowners receive a direct and unique benefit from a public improvement. Generally, the cost of the improvement is allocated to property owners within the defined benefit zone and collected in conjunction with property or sales taxes over a predetermined number of years. The assessment is eliminated once the annual assessment collections cover the cost of the improvement (or debt issued to pay for the improvement) (Federal Highway Administration Center for Innovative Finance Support, n.d.-a).

Development Impact Fees

Development impact fees and excise taxes are one-time charges collected from developers or property owners to fund public infrastructure and services made necessary by new development. Impact fees are most successfully implemented in areas poised for significant growth with little or no existing development. Generally, rates are based on a formula that takes into consideration the number of new dwelling units or square feet of nonresidential space and the relative benefit the infrastructure provides the property. For transportation projects, relative benefit is usually determined by a development’s distance from the improvement (Federal Highway Administration Center for Innovative Finance Support, n.d.-a).