The Comprehensive Autism Care Demonstration: Solutions for Military Families (2025)

Chapter: 4 ABA Industry Guidelines and Standards of Care

4

ABA Industry Guidelines and Standards of Care

This chapter reviews the recent professionalization of the applied behavior analysis (ABA) industry and integration into healthcare systems and industry guidelines and standards of care for ABA services. It also discusses the extent in which the policies and practices of the Comprehensive Autism Care Demonstration (ACD) adhere with these guidelines and standards of care in response to the committee’s charge to review guidelines and standards of care (see Chapter 1, Box 1-3).

It is important to note that the committee recognizes that TRICARE is a statutorily defined health benefit program managed by the Defense Health Agency (DHA) under the leadership of the Assistant Secretary of Defense, Health Affairs, and that it is not a health insurance plan and does not operate the same as commercial and public insurance plans. This includes not being subject to mandates or provisions included in the Affordable Care Act, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), or the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA). However, in practice, military-connected families receiving coverage under TRICARE and ABA providers delivering services to these beneficiaries experience the health benefit program in similar ways as one might experience other healthcare coverage. As such, the committee examines available guidelines and standards of care as if they could apply to all types of health benefits and healthcare plans.

GENERALLY ACCEPTED STANDARDS OF CARE

This section reviews the history and development of generally accepted standards of care (GASC) for the delivery of ABA services. It draws on background provided to the committee through a commissioned paper (Green, 2025) and public presentations (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2024a). For behavioral and mental health, the term GASC is defined broadly as delineation of the best practices for serving patients with a specified condition that are widely accepted by professionals in the relevant clinical specialty. They are developed and revised periodically by subject matter experts in that profession, who typically base the standards on an analysis of the applicable scientific research and the consensus of clinicians who serve the patient population.

There are several national nonprofit organizations that have set guidelines related to ABA, including the Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI); the Applied Behavior Analysis Coding Coalition; the Autism Commission on Quality; the Association for Professional Behavior Analysts; Autism Speaks; the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB); and the Council of Autism Service Providers (CASP).

Within health care, standards of care can be broadly defined and may include clinical practice guidelines, quality and safety standards, and ethical codes of conduct. While compliance is often voluntary, guidelines and standards can be essential for ensuring quality, regulatory adherence, and creating trust among stakeholders (Dubuque, 2024). MHPAEA, and some state mental health parity laws and rules, require healthcare plans to base determinations of medically necessary services for beneficiaries with mental health and substance use disorders on GASC, also called generally recognized independent standards of current medical practice (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d., 2024). These laws and rules designate valid sources of such standards, including peer-reviewed scientific studies, clinical practice guidelines, and recommendations of nonprofit healthcare provider associations in the relevant clinical specialty, specialty societies, and federal government agencies. See Box 4-1 for more information about MHPAEA.

The mental health parity provisions under MHPAEA currently do not apply to the TRICARE health benefit program. However, the Department of Defense (DoD) has committed to fair access to behavioral healthcare services in its health benefit program (see, for example, DoD final rule in TRICARE; Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Treatment, 2016).

The first standards of ABA health care for autistic individuals were laid out in Guidelines: Health Plan Coverage of Applied Behavior Analysis Treatment for Autism Spectrum Disorder, published by the BACB in 2012 (BACB, 2012). These guidelines were updated in 2014 and retitled Applied Behavior Analysis Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Practice Guidelines for

BOX 4-1

Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act

The Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA) is a federal law that generally prevents group health plans and health insurance issuers that provide mental health or substance use disorder benefits from imposing less favorable benefit limitations on those benefits than on medical/surgical benefits, known as parity provisions. This law was in some ways an expansion of the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 (MHPA), which established some similar parity provisions, stipulating that large group health plans cannot impose annual or lifetime dollar limits on mental health benefits that are less favorable than any such limits imposed on medical/surgical benefits. MHPAEA preserved MHPA protections and added significant new protections (U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2024).

MHPAEA helps ensure most plans include preventive behavioral health services such as depression screening and behavioral assessments for children. The law prohibits health plans from charging higher copayments, having separate deductibles, or imposing more restrictive requirements on care management functions (such as preauthorization or medical necessity reviews for these services) than they do for covered medical/surgical services (U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2024; Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, 2021). Furthermore, MHPAEA prohibits quantitative treatment limitations (QTLs) and nonquantitative treatment limitations (NQTLs) that place limits on mental health services, unless limits are also applied to all outpatient medical/surgical benefits. Dollar or hourly cap limitations are examples of QTLs. Examples of NQTLs include prior authorization, medical necessity criteria, and progress standards (NASEM, 2024a). Autism has been classified as mental health condition by many states and health plans. As such, the MHPAEA provides a mechanism to seek the same level of coverage for services designed to support autism as would be provided for traditional physical/medical conditions.

As originally crafted, the act only applied to group health plans, group health insurance coverage, and Medicaid managed care. However, the Affordable Care Act made mental health and substance use disorder coverage essential benefits and extended application of these parity provisions to the individual health insurance market, commercially insured small employer group market, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, though not to Medicare, Medicare Advantage Plans, or traditional fee-for-service Medicaid (NASEM, 2024c).

Healthcare Funders and Managers (BACB, 2014). In 2020, the BACB transferred the development of the guidelines to CASP, a nonprofit trade association for organizations that provide ABA services to people with autism. Based on review and input from subject matter experts in behavior analysis, psychology, medicine, healthcare laws, and public policies and consumers of ABA services, a third edition was released in 2024, Applied Behavior Analysis Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Guidance for Healthcare Funders, Regulatory Bodies, Service Providers, and Consumers

TABLE 4-1 Adoption of Key Standards and Public Policies

| Year(s) | Action or product |

|---|---|

| 1968 | Dimensions of applied behavioral analysis (ABA) defined by Baer, Wolf, & Risley (1968) |

| 1983 | First formal behavior analysis certification program begins, established by State of Florida Developmental Services Office |

| 1998 | Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) established to develop national standards (education, experiential training, exam, continuing education, ethics) and programs for credentialing professional behavior analysts |

| 1999 | BACB begins issuing Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) and Board Certified Assistant Behavior Analyst (BCaBA) credentials |

| 2007 | Law requiring certain commercial health plans to cover ABA services for people with autism adopted in South Carolina |

| 2007–2019 | Remaining states adopt laws or rules requiring certain commercial health plans to cover ABA services for people with autism |

| 2009 | First behavior analyst licensure laws adopted in Nevada and Oklahoma |

| 2010–2024 | Additional 36 states adopt behavior analyst licensure laws |

| 2012 | Guidelines: Health Plan Coverage of Applied Behavior Analysis Treatment for Autism Spectrum Disorder published by BACB |

| 2014 | Applied Behavior Analysis Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Practice Guidelines for Healthcare Funders and Managers published by BACB |

| 2014 | Category III (temporary) health insurance billing codes for ABA services issued by American Medical Association CPT Editorial Panel |

| 2014 | BACB develops national standards and program for credentialing behavior technicians (paraprofessionals) |

| 2015 | BACB begins issuing Registered Behavior Technician (RBT) credential |

| 2016 | Healthcare provider taxonomy codes for Behavior Analyst, Assistant Behavior Analyst, and Behavior Technician issued by American Medical Association National Uniform Claims Committee |

| 2019 | Category I CPT codes for ABA services issued by American Medical Association CPT Editorial Panel |

| 2024 | Applied Behavior Analysis Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Guidance for Healthcare Funders, Regulatory Bodies, Service Providers, and Consumers (3rd ed.) Published by Council of Autism Service Providers |

SOURCE: Green, 2025.

(3rd ed.) (CASP, 2024). Table 4-1 illustrates the rollout of guidelines and revised editions in relation to other developments in the ABA industry. The CASP guidelines have been recently cited as an accepted source of clinical criteria in regulations for implementing the provision in the California Mental Health Parity Act (Cal. Code Regs. tit. 28 § 1300.74.721).

ABA PROVIDERS

As interest in using ABA grew, more programs for certifying professionals in the practice of ABA were developed. One of the first programs, the Florida Behavior Analysis Certification Program, started in 1983 and operated until 1998, when it transitioned into the nonprofit BACB. Since 1999, the BACB has served as a certification organization for behavior analyst professionals. The BACB’s mission is to protect consumers of behavior-analytic services by systematically establishing, promoting, and disseminating professional standards of practice.

Throughout the years, BACB has conducted four job task analyses; updated examination contents and eligibility requirements (degrees, coursework, supervised experiential training) accordingly; converted exams from pencil-and-paper to a computer-based format; developed and enforced ethical standards; and certified thousands of professional behavior analysts. It has also developed a paraprofessional credentialing program, the Registered Behavior Technician (RBT) credential, which is described in more detail below (Carr & Nosik, 2017; Johnston, Carr, & Mellichamp, 2017).

BACB Certification

BACB requirements for certification include specifications for the levels of education, training, experience, examination, adherence to an ethics code, and in some cases ongoing supervision. The BACB currently certifies professional practitioners of ABA at two levels:

- BCBA—an independent practitioner who can provide ABA services and supervise delivery of those services by others. Requires at least a master’s degree, university coursework in specified topics, supervised experiential training, and passage of the BCBA professional examination in behavior analysis. BCBAs with doctoral degrees can apply for the Board Certified Behavior Analyst-Doctoral (BCBA-D) designation.1

- Board Certified Assistant Behavior Analyst (BCaBA)—a practitioner who can provide ABA services under the supervision of a BCBA or BCBA-D. Requires a bachelor’s degree, university coursework in specified topics in behavior analysis, supervised experiential training, and passage of the BCaBA professional examination in behavior analysis.2

___________________

1 For more information on BCBAs, see https://www.bacb.com/bcba/

2 For more information on BCaBAs, see https://www.bacb.com/bcaba/

Both of these certification programs have been accredited since 2007 by the National Commission for Certifying Agencies (NCCA) of the Institute for Credentialing Excellence (Carr & Nosik, 2017; Johnston, Carr, & Mellichamp, 2017). To maintain their certifications, BCBAs and BCaBAs need to complete continuing education requirements and adhere to an ethics code (BACB, 2020, 2025).

The BACB currently certifies paraprofessional practitioners of ABA at one level:

- RBT—a paraprofessional practitioner required to work under the direction and close supervision of professional behavior analysts who have met BACB requirements for serving as supervisors. Current requirements are at least a high school education or equivalent, passage of a criminal background check, completion of a BACB-approved 40-hour training program, passage of an initial competency assessment, and passage of the RBT examination in behavior analysis.

The RBT program was developed in 2017 by the BACB. It is also accredited by the NCCA. To maintain their credential, RBTs are asked to adhere to an ethics code (BACB, 2021) and their supervisors document that they have fulfilled the supervision requirements.

As of the end of 2023, certifications totaled more than 66,000 BCBAs, more than 5,600 BCaBAs, and more than 163,000 RBTs, with the vast majority located in the United States (Luke, 2024). There has been tremendous growth in certificants across the three areas in the past decade (see Figure 4-1). Growth in the field was likely spurred by availability of funding, which led to industry development and university-level training. Notably, more than 70% of certified professionals purport to working with autistic individuals.

State Licensure

Starting in 2009, U.S. states began adopting laws that require individuals to hold a state-issued license in order to use a specified title (e.g., Licensed Behavior Analyst) and, in all but two states, to practice ABA professionally (the Oregon and Wisconsin laws are title acts only). At this writing, 39 states have adopted behavior analyst licensure laws (BACB, n.d.). All of these states license behavior analysts with graduate degrees to practice ABA independently. Several states also license assistant behavior analysts with bachelor’s degrees to practice under the supervision of licensed behavior analysts. Most states exempt behavior technicians and other paraprofessionals

NOTE: BCaBA = Board Certified Assistant Behavior Analyst; BCBA = Board Certified Behavior Analyst; RBT = Registered Behavior Technician.

SOURCE: Luke, 2024.

from direct regulation by the state as long as they are supervised properly by a licensed behavior analyst or assistant behavior analyst. At present, five states require ABA paraprofessionals to be registered or certified by the state licensing entity in addition to being supervised by a licensed professional behavior analyst.

Behavior analyst licensure programs are administered by governmental entities that vary across states (e.g., stand-alone behavior analyst licensing boards, omnibus licensing boards, licensing boards of other professions, state agencies with no licensing board). In all states, however, behavior analysts are licensed in their own right, not as members of other professions. Because the requirements for the BACB’s professional certifications parallel requirements for licenses in many professions—degree(s), university coursework, experiential training, professional exam in the subject matter—most of the licensure laws and/or the associated rules make current BACB certification a qualification for obtaining the state-issued license. In the remaining states, BACB certifications are written into various laws and rules as qualifications for designing, overseeing, and/or delivering ABA services (e.g., health insurance laws or rules, Medicaid policies, developmental disability services laws or rules, education laws or rules).3

___________________

3 For a list of states and links to the regulatory entities, see https://www.bacb.com/u-s-licensure-of-behavior-analysts/

Health Care Provider Taxonomy Codes

Adoption of the public policies described above made it possible for many ABA providers to have their services funded by health insurance and placed them squarely within the category of behavioral healthcare providers. Several additional actions were required, however, to enable health insurance reimbursement for ABA services. One was the establishment of Health Care Provider Taxonomy codes, which are unique 10-digit numbers used to classify a set of healthcare providers by their areas of specialization. Healthcare providers use these codes to apply for the National Provider Identification (NPI) numbers that are required to bill health plans, including Medicare. These taxonomy codes are issued and owned by the American Medical Association (AMA) National Uniform Claim Committee. Codes for behavioral analysts and technicians were issued in 2016 pursuant to an application submitted by the BACB and Association of Professional Behavior Analysts.4

Current Procedural Terminology Codes

To be reimbursed by public and commercial health plans in the United States, healthcare providers use billing codes linking to procedures and services. When the first state laws requiring health plans to cover ABA services for autistic beneficiaries were adopted, there were no billing codes that were specific to those services. Health plans and providers used existing codes, selected mainly from the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System maintained by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, that came reasonably close to describing ABA services (e.g., H2019, “therapeutic behavioral services”). To enable ABA providers to bill health plans appropriately, it was necessary to obtain Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for ABA services.5

In 2014, the AMA CPT Editorial Panel issued 16 Category III (temporary) CPT codes for adaptive behavior/ABA services pursuant to a process initiated by the ABAI. In 2019, the Panel issued eight revised codes as Category I with two revised codes remaining Category III, replacing the original Category III code set. Of these 10 revised codes, three are for adaptive behavior/ABA assessment services and seven are for treatment services; and of the seven treatment services codes, there are three for services delivered to a single individual, two for services delivered in small groups, and two for guidance to families. See Box 4-2 for descriptions of these codes. Some

___________________

4 The ABA provider codes are under Behavioral Health & Social Service in the Health Care Provider Taxonomy Code Set. For more information, see https://taxonomy.nucc.org/

5 CPT codes are issued, owned, and managed by the AMA CPT Editorial Panel. For more information, see https://www.ama-assn.org/about/cpt-editorial-panel/cpt-code-process

BOX 4-2

ABA Billing Codes

For Adaptive Behavior Assessment

97151. Behavior identification assessment, administered by a physician or other qualified health care professional, each 15 minutes of the physician’s or other qualified health care professional’s time face-to-face with patient and/or guardian(s)/caregiver(s) administering assessments and discussing findings and recommendations, and non-face-to-face analyzing past data, scoring/interpreting the assessment, and preparing the report/treatment plan

97152. Behavior identification supporting assessment, administered by one technician under the direction of a physician or other qualified health care professional, face-to-face with the patient, each 15 minutes

0362T (Category III). Behavior identification supporting assessment, each 15 minutes of technicians’ time face-to face with a patient, requiring the following components:

- administered by the physician or other qualified health care professional who is on site,

- with the assistance of two or more technicians,

- for a patient who exhibits destructive behavior,

- completed in an environment that is customized to the patient’s behavior.

For Adaptive Behavior Treatment

97153. Adaptive behavior treatment by protocol, administered by technician under the direction of a physician or other qualified health care professional, face-to-face with one patient, each 15 minutes

97154. Group adaptive behavior treatment by protocol, administered by technician under the direction of a physician or other qualified health care professional, face-to-face with two or more patients, each 15 minutes

97155. Adaptive behavior treatment with protocol modification administered by physician or other qualified health care professional, which may include simultaneous direction of technician, face-to-face with one patient, each 15 minutes

97156. Family adaptive behavior treatment guidance, administered by physician or other qualified health care professional (with or without the patient present), face-to-face with guardian(s)/caregiver(s), each 15 minutes

97157. Multiple-family group adaptive behavior treatment guidance, administered by a physician or other qualified healthcare professional (without the patient present), face-to-face with multiple sets of guardians/caregivers, every 15 minutes

97158. Group adaptive behavior treatment with protocol modification, administered by physician or other qualified health care professional face-to-face with multiple patients, each 15 minutes

0373T (Category III). Adaptive behavior treatment with protocol modification, each 15 minutes of technicians’ time face-to-face with a patient, requiring the following components:

- administered by the physician or other qualified health care professional who is on site,

- with the assistance of two or more technicians,

- for a patient who exhibits destructive behavior,

- completed in an environment that is customized to the patient’s behavior.

SOURCE: Committee generated with information from ABA Coding Coalition, n.d.

codes are for services administered by behavior technicians under the direction of qualified health professionals. Qualified health professionals are considered licensed behavioral analysts, BCBAs, or licensed psychologists who have competence in behavior analysis (American Medical Association, 2018). None of the code descriptors for ABA are restricted to any specific diagnoses or patient populations.6

Commercial and Public Insurance Coverage for ABA Services

Since 2019, all 50 states have adopted laws or issued regulatory guidance requiring certain commercial health insurance plans to cover ABA services for individuals with autism (Autism Speaks, 2020b). These state mandates typically apply to fully insured plans, including those sold through the individual and small group markets, and state employee health benefit plans. In addition, private health insurance plans purchased through the Health Insurance Marketplace in 33 states and the District of Columbia include coverage for ABA services (Autism Speaks, 2022a).

Self-funded employer-sponsored health plans, which are regulated under ERISA and not subject to state insurance mandates, vary in their ABA coverage (Autism Speaks, 2022c). As of 2018, approximately 45% of companies with 500 or more employees included coverage for ABA or similar behavioral health services for individuals with autism (Autism Speaks, 2022c).

At the federal level, all plans within the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program have been required to cover ABA services for individuals

___________________

6 For more information, see Billing Codes, Resources, and FAQs at www.abacodes.org

with autism since 2017 (U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 2017). Similarly, the Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs has included ABA as a covered benefit since December 2020 (Autism Speaks, 2020a; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2023). Coverage through the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) varies by state when not part of state Medicaid programs (Autism Speaks, n.d.a). Under Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) mandate, state Medicaid programs are required to provide all medically necessary services for beneficiaries under age 21. From 2014 to 2022, state agencies sought to clarify ABA as a covered benefit under EPSDT in Medicaid plans or regulations (Autism Speaks, 2022b).

During these developments in health benefit coverage, policies, benefit designs, and ultimately administration of and access to ABA services have varied across states and plans. Some of this variation has included differences in financial caps, age eligibility, limits on hours of ABA per week, and qualifications of diagnosing providers and those administering ABA services (Autism Speaks, 2020b; DoD, 2024b). More recently, since amendments to MHPAEA in 2021, the Department of Labor Employee Benefits Security Administration has conducted outreach and enforcement efforts to address common deficiencies in health benefit plans related to mental health parity, including those that exclude or limit ABA for treatment of autism (Employee Benefits Security Administration, 2023, 2025).

INDUSTRY GUIDELINES FOR KEY ASPECTS OF ABA

In its review of industry guidelines and standards of care in the provision of ABA, the committee drew on the healthcare literature, testimonies to the committee, the CASP guidelines (CASP, 2024), and available public information from commercial insurance7 as well as TRICARE policies for the ACD (DHA, 2023a). It focused on the following areas: determination of medical necessity, treatment plans and delivery of ABA services, evaluation of progress (assessment practices), billing and reimbursement, caregiver training and involvement, and care coordination or navigation. Each of these areas is described further below.

Table 4-2 provides an overview of how other plans interpret standards of care in their coverage of ABA and how the ACD policies compare on

___________________

7 The committee compared ABA coverage across seven major for-profit health insurance providers. The committee was able to identify public documents detailing coverage for ABA services from Cigna Healthcare, Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield, UnitedHealthcare, Molina Healthcare, Magellan Health, Aetna, and Kaiser Permanente. It assembled and reviewed policy in the following areas: Standards of Reliable Evidence for ABA Coverage, Determination of Medical Necessity, Diagnoses/Screening and Referrals, Billing and Payment, Utilization Management, Service Delivery, Credentialing, and Access.

| CASP Guidelines (CASP, 2024) | Commercial Insurance (see Appendix G)a | ACD Policies (DHA, 2023a) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Determination of Medical Necessity or Access to ABA Services | The guidelines focus on ABA as an intervention for autistic individuals but note that ABA is effective for other conditions as well. Those with autism often have co-occurring conditions (Part 3, pp. 15–18). | Beneficiary has met clinical criteria as determined by a qualified provider, which can include reasonable expectation of improvement with ABA; established diagnosis (usually autism); demonstrated functional impairment,b developmental delay, and/or challenging behavior that presents health or safety risk to self or others. One payor has age restrictions (under 9 years old). | The beneficiary needs to receive an autism diagnosis by approved diagnosing provider using the DSM-5 criteria and one of five validated assessment tools (see Chapter 2). The DSM criteria is to be documented in a DHA-approved checklist (4.2.1; 4.2.1.2). |

| Treatment Plans | The delivery of quality ABA services requires careful planning by the behavior analyst. The treatment plan is based on information gathered during assessment, ongoing data review, and best practices (Section 4.2). | Expectation that a formal treatment plan is developed with goals and periodic assessments. Several payors identify specific features of the plan. | Treatment plan is a written document outlining the ABA service plan of care for the individual, including the expected outcomes of autism symptoms, based on the initial ABA assessment that is revised and updated based on periodic reassessments of beneficiary progress toward the objectives and goals (8.7.1.5; 8.7.1.7). |

| Goals of ABA Services | Goals are to be individualized and medically necessary for the patient. Treatment plans should include long-term as well as short-term goals (Section 4.2, p. 37). | Objectives that are measurable and tailored to the beneficiary with focus on communication skills, adaptive skills, and appropriate behavior. Can include adaptive living skills such as eating and food preparation, toileting, and personal self-care. | The treatment plan needs to clearly define measurable targets, including parent/caregiver goals and objectives and goals individualized to the strengths, needs, and preferences of the beneficiary and his/her family members. The goals have to address core symptoms of autism as defined by the DSM-5 (8.7.1.5; 8.7.1.6). Goals targeting functional/activities of daily living skills are excluded (8.10.19). |

| Amount of ABA (Intensity) | The number and complexity of goals should determine scope of treatment, the intensity level, and the settings in which it is delivered (Section 4.2, p. 33). | The level of impairment will justify number of hours requested. Often state not to exceed 40 hours/week. Generally authorized as time-limited (1 to 2 years) unless more is demonstrated to be medically necessary. | Recommended hours of ABA services should be submitted based on symptom domains, levels of support required per DSM-5 criteria, results of assessments, and the capability of the beneficiary to participate actively in ABA services. If recommended hours are not being rendered, an explanation is required to be documented in the subsequent treatment plan (8.7.1.6; 8.7.1.6.1). |

| CASP Guidelines (CASP, 2024) | Commercial Insurance (see Appendix G)a | ACD Policies (DHA, 2023a) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Settings | Care can be deliverable in any setting that is relevant for the patient to achieve treatment goals (Section 4.2, p. 38). | Provided in an environment that is most conducive to achieving goals. | Billing for services outside of the home, clinic, office, school, or telehealth is excluded. Certain community settings such as sporting events, camps, and other settings are also excluded (8.10.11). ABA services in the school setting are limited by the role of the behavior analyst (e.g., a BCBA, not technician), who is targeting a specific behavior excess or deficit, and are for a limited duration (8.10.15). |

| Safety Measures | Behavior analysts are charged with guiding implementation of a crisis management as necessary. Some patients display significant challenging behaviors that require treatment in specialized settings (e.g., intensive outpatient, day treatment, residential, or inpatient programs). Such treatment typically requires high staff-to-patient ratios (e.g., two to three staff members for each patient) and close on-site direction by the behavior analyst. These programs often utilize specialized equipment and treatment environments, such as observation rooms and room adaptations, which aid in maintaining the safety of both patients and staff (Section 4.2, p. 40). | One payor notes that crisis management for medical and behavioral emergencies should be included in treatment plan. | Billing for ABA services using aversive techniques, including restraints, is excluded (8.9.8.1). |

| Qualified Provider | Tiered service delivery models utilize treatment teams working under the direction of behavior analysts. These models have been the primary mechanism for most ABA services, although there may be instances in which a behavior analyst provides all services, including direct treatment for a patient based on their individual needs (Section 2.2; Section 2.3). | ABA techniques to be performed by licensed or certified behavior analyst (or similarly qualified) OR trained technicians or paraprofessionals acting under supervision of qualified ABA provider. | Authorized ABA supervisors have a master’s degree or above in qualifying field and are licensed or certified; assistant behavior analysts have a bachelor’s degree or above and are licensed or certified; and behavior technicians have appropriate certification and receive ongoing supervision (11.10; 11.9; 11.17). |

| Evaluation of Progress | Progress should be determined by the treating behavior analyst who has aligned data collected with anticipated outcomes. Assessment should be a multi-method, multi-informant approach using reliable, well-established instruments that are appropriate for the individual patient characteristics (Section 4.1, pp. 19–28; Section 4.4, pp. 51–54). | Evaluation of progress to be performed every six months to assess gains toward goals and need for continuing ABA; a repeated assessment using a validated tool has to be done every 6–12 months to demonstrate response. Suggestions for validated tool are often offered but none specifically required. | Evaluation of progress will include baseline functioning and cumulative periodic assessments (every six months) using, at a minimum, the identified outcome measures (PDDBI, Vineland-3, SRS; 8.6.4; 9.1.2.2). |

| Billing and Reimbursement | N/A | Coverage is provided for assessment, direct ABA services, and caregiver training. Some payors note specific CPT codes: 97151, 97152, 97153, 97154, 97155, 97156, 97157, 97158, 0362T, 0373T. | Only some of the CPT codes are authorized (8.11.6). Excluded are 97152, 97154, 0362T, and 0373T. Further, use of code 97155 is limited and cannot be billed concurrently with code 97153 (8.11.7.3.8). |

| CASP Guidelines (CASP, 2024) | Commercial Insurance (see Appendix G)a | ACD Policies (DHA, 2023a) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Training for Parents/Guardians | Coverage of ABA treatment should not be excluded, denied, or limited based on the degree of caregiver participation (Section 4.2, p. 46). | Expectation that caregivers commit to participate in the goals of treatment plans and are provided necessary support and training to reinforce interventions. | Behavior analyst to submit recommendation for the number of monthly hours and measurable objectives. A minimum of six parent/caregiver sessions are required every six months with some setting restrictions. Participation by the parent(s)/caregiver(s) is required, and re-authorization for ABA services is contingent upon their involvement. Reasons for non-participation and attempts to mitigate should be documented (8.7.1.6.1). |

| Care Navigation | For some individuals with co-occurring conditions and other regular healthcare providers (e.g., occupational therapists), co-treatment and coordination of care may be necessary. The need for coordination of care should be individualized to the needs of the patient and the additional services they have received (Section 4.6, pp. 62–63). | One payor notes that the treatment plan will include evidence of coordination of services with the recipient’s other treatment providers. | The contractor shall assign an Autism Services Navigator to all new beneficiaries on or after October 1, 2021 and to all ACD participants after January 1, 2025. The Navigator will develop a written comprehensive care plan to document ABA and other services and transition timelines (6.1; 6.2). |

aThe information in the table is a generalized description of coverage for ABA services across the seven payors reviewed. See Appendix G for specific details by payor.

bMany commercial payors require a standardized scale of functioning to demonstrate functional impairment. No particular scale is required but some are suggested (see Appendix G).

key aspects of ABA delivery. For more details on this review of policies, coverage, and requirements, see CASP guidelines (CASP, 2024), our review of commercial insurance plans (Appendix G), and TRICARE Operations Manual (DHA, 2023a).

Determination of Medical Necessity

Medical necessity is a term that payors use to describe the process for determining whether they will cover a specific service or treatment. While specific criteria for determining medical necessity vary between payors, determinations generally adhere to common principles described by American Medical Association (2023) and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) (Giardino et al., 2022) to ensure treatment is

- in accordance with generally accepted standards of medical practice;

- clinically appropriate for the individual in terms of type, frequency, extent, site, and duration;

- not primarily for the economic benefit of the health plans and purchasers or for the convenience of the individual, treating physician, or other healthcare provider;

- based on the best scientific evidence, considering the available hierarchy of medical evidence; and

- likely to produce incremental (and/or future) health benefits relative to the next best alternative that justify any added cost.

Additionally, all 50 states’ Medicaid programs have definitions of medical necessity that are used in determining coverage for EPSDT benefits that states are required to cover under federal law.8 In general, states define medically necessary services as those that improve health or lessen the impact of a condition, prevent a condition, or restore health (National Academy for State Health Policy, 2021).

When determining medical necessity for ABA treatment, payors typically followed principles set out by the AMA, AAP, and state Medicaid programs. However, payors tend to have medical necessity guidelines that are specific to ABA coverage, as is the case with other specialty treatments.

The following list of medical necessity criteria is summarized from publicly available health plan guidelines from Cigna Healthcare,9 Anthem Blue

___________________

8 For a full comparison of definitions across all 50 states, see https://nashp.org/state-tracker/state-definitions-of-medical-necessity-under-the-medicaid-epsdt-benefit/

9 For more information about Cigna Healthcare, see https://static.evernorth.com/assets/evernorth/provider/pdf/resourceLibrary/behavioral/mm_0499_coveragepositioncriteria_intensive_behavioral_interventions.pdf

Cross Blue Shield,10 UnitedHealthcare,11 Molina Healthcare,12 Magellan Health,13 and Kaiser Permanente14:

- Diagnosis—a diagnosis needs to be based on criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; APA, 2013) by a healthcare professional who is licensed to practice independently and whose licensure board considers diagnostics to be within their scope of practice

- Clinical appropriateness—treatment is in accordance with generally accepted medical standards of care for the diagnosed condition and has been determined effective for that condition including intensity and duration guidelines

- Convenience—treatment is required and not undertaken primarily for the convenience of either the individual or provider

- Level of service—appropriate level of service is identified for the individual including functional improvement requirements

- Comprehensive assessment of functional impairments in communication, behavior, and social skills completed by a professional trained to administer the assessment tool and interpret the result

- ABA planning that includes baseline assessments and individualized goals based on identified functional deficits

- Periodic review for the continuation of service including identification of new or continuing treatment goals and treatment planning

These criteria as well as standard care practices (discussed below) recognize three important and separate “assessment” stages related to the delivery of ABA: (1) assessment related to diagnosing autism in an individual; (2) initial assessment before starting ABA to identify goals, needs, target behaviors, etc. and develop treatment plan; and (3) ongoing assessment to track progress, revisit goals and plan, and determine continued

___________________

10 For more information about Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield, see https://web.archive.org/web/20220622035206/https://www.anthem.com/dam/medpolicies/abc/active/guidelines/gl_pw_c166121.html

11 For more information about UnitedHealthcare, see https://dev.providerexpress.com/content/dam/ope-provexpr/us/pdfs/clinResourcesMain/autismABA/abaSCC.pdf

12 For more information about Molina Healthcare, see https://www.molinamarketplace.com/marketplace/ca/en-us/Providers/-/media/Molina/PublicWebsite/PDF/Providers/common/BI/2024/2024-Autism-Spectrum-Disorder.pdf

13 For more information about Magellan Health, see https://www.magellanprovider.com/media/45694/mcg.pdf

14 For more information about Kaiser Permanente, see https://healthy.kaiserpermanente.org/content/dam/kporg/final/documents/community-providers/mas/ever/mas-aba-provider-guide.pdf

need for ABA. Available standardized assessment tools might be appropriate at any of these stages.

Diagnosis assessment is conducted by board-certified and qualified healthcare providers (e.g., pediatric physicians, nurse practitioners, and specialty providers). As discussed in Chapter 2, diagnosing autism is a complex clinical process based solely on assessments of behavior using observations or historical reports of behavior. The DSM-5 criteria help ensure consistency and reliability in the diagnosis of autism across healthcare providers. In addition, several objective measures and standardized diagnostic tools have been developed to help clarify observations and information on individuals’ behaviors. However, while meaningful, these tools are not uniformly available and a valid diagnosis need not be contingent on their use.

At other stages of assessment in planning and monitoring ABA services, professional behavior analysts assess clients’ strengths and weaknesses in multiple skill domains (cognitive, communication, social, self-help, maladaptive behaviors, etc.), as well as the preferences and circumstances of the clients and their families. Skills that need to be developed can be broken down into small components. Behavior analysts develop written protocols for technicians or paraprofessionals (see tiered delivery model below) as well as caregivers (see caregiver engagement and training below) to follow to help individuals develop skills. Behavior analysts monitor the implementation of protocols, review data on clients’ progress frequently, and adjust treatment protocols as needed (NASEM, 2024a). See further discussion on evaluating progress below.

Treatment Plans and Delivery of ABA Services

For delivery of ABA, a treatment plan is put together by the behavior analyst, who documents initial and ongoing assessments, individual goals and objectives, and proposed approach to ABA for the client as well as training and support for the caregiver. Section 4.2 of the CASP guidelines (CASP, 2024) covers many aspects of developing and delivering ABA treatments plans. Coordination with other healthcare professionals will be useful for planning treatment as well as assessing progress with ABA. Other professionals can provide assessments of an individual’s general cognitive functioning, speech and language skills, specific learning disabilities, dental health, and medical status (including co-occurring conditions). It is important to develop an understanding of a client’s strengths and challenges and to be aware of other interventions and medical services. Some aspects of treatment plans and ABA delivery are summarized in the following sections: scope and goal development, amount of ABA, settings and modality, safety measures and crisis management, and tiered delivery and staffing.

Scope and Goal Development

As discussed further in Chapter 5, the scope of intervention may be comprehensive (targeting multiple behaviors in multiple domains such as self-care, language and communication, and reduction of challenging behavior) or focused (targeting a limited number of behaviors). Comprehensive ABA treatment typically seeks to enable the client to develop and/or maintain many adaptive behaviors and may also address any maladaptive behaviors that jeopardize the client’s health or safety. Focused ABA treatment may address only a small number of adaptive behaviors from one or two domains, such as specific self-care skills. If one or more maladaptive behaviors are targeted, the professional ethical standards guide ABA providers to also target one or more adaptive behaviors that compete with or are alternatives to the maladaptive behavior(s) (CASP, 2024).

Goals refer to the aim(s) of treatment—that is, the behaviors that are targeted for treatment and the nature and amount of improvement that is sought. Individual goals or targets are determined by ABA providers drawing on information about a client’s and family’s needs, strengths, and life circumstances. Treatment plans often include short-term and long-term goals. Protocols or written procedures in the treatment plans can guide ABA providers in implementing assessment and treatment of each goal (CASP, 2024).

Many healthcare professionals recognize activities of daily living (ADLs) are valid targets for ABA. While ADLs can refer to a range of functional tasks individuals complete regularly and independently (Matson, Hattier, & Belva, 2012), for healthcare contexts and medical decision making, ADLs often refer to critical health and safety tasks. These fundamental self-care tasks have been codified in 26 U.S.C. § 7702B(c)(2) under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act as activities related to eating, toileting, transferring, bathing, dressing, and continence. In some circumstances, these fundamental tasks are known as basic ADLs in contrast to instrumental ADLs that are less crucial to daily functioning but useful for independent living (e.g., meal preparation and money management). Medical conditions, such as autism, can affect one’s ability to perform ADLs.

The ACD currently limits goals of ABA services to those targeting the core symptoms of autism and specifically excludes ADLs. Commercial payors generally cover a broader set of goals that meet individual health needs, including ADLs or adaptive living skills. The committee heard quite a bit from ABA providers and military-connected families on the importance of targeting goals around basic ADLs. See Box 4-3.

Amount of ABA (ABA Intensity)

In many ABA outcome studies as well as in the CASP standards (CASP, 2024), the amount of ABA (also referred to as ABA intensity or ABA

BOX 4-3

Perspectives on Activities of Daily Living

The committee’s information gathering included listening sessions and a call for public input to understand experiences with the ACD and ABA. While not meant to be representative and reflect the full range of perspectives or experiences of individuals and military families, this information provides important context for understanding the experience of those enrolled in the ACD and those receiving or providing ABA services, as well as the experience of those living with autism. This input served as a backdrop for the committee’s review and assessment of the available empirical literature, as well as a reminder of the real-life stories and experiences behind the data. This provided context for, though not the basis of, its conclusions and recommendations. This box presents some of the comments that the committee received regarding coverage for ADLs, such as showering, dressing, toileting, and basic hygiene.

“Before the TRICARE Operations Manual was updated, our BCBA in Washington State helped us with critical life skills, also known in the operations manual as activities of daily living (ADLs). I can proudly say that [my son] was successfully potty trained because of the help of the BCBA. I could not have done it without their help. [. . .] I was extremely discouraged when TRICARE no longer allowed BCBAs to include ADLs as session goals. Placing [responsibility for] ADL goals solely on the parents sets them up for failure, especially new parents whose child was recently diagnosed [. . . It is a] struggle to teach special needs kids critical life skills that often require creative approaches [different] from their neurotypical peers.” ~ Public comment made by a Navy spouse and mother of a non-verbal child with autism at the June 20, 2024, public session

“The ACD is difficult to work under as it restricts providers from being able to provide all the services needed. An example of this would be that ACD does not allow providers to teach daily living skills. This prevents clients from learning to be independent.” ~ Written input to committee from BCBA in Texas

“Tricare limits/restricts what services ABA providers can offer our kids on the spectrum too much! Many of the life skills that autistic children need to learn (i.e., toileting, brushing teeth, healthy eating, preparing food) are skills that can be affected by their rigidity, task or demand avoidance, and/or sensory issues.” ~ Written input to committee from parent in Virginia

“Only kid in the clinic I couldn’t work on toilet training with was an 8-year-old non-verbal child with TRICARE. We lost a year of therapy in many key areas until he switched to [another health plan].” ~ Written input to committee from BCBA in Michigan

“I was at a loss trying to figure out, what are we gonna do? Because our whole focus, based on [my son’s] profound autism, was trying to get him as independent as possible. I’m still working with [my son] every morning on independent skills,

such as showering, looking both ways when we cross the street, and even tying his shoes.” ~ Public comment made by an Army parent of a son with profound autism at the April 12, 2024, public session

“[My son] is still in diapers at nine years old [. . .] He still needs that support [from the ACD]. He still needs that help, but it has just been absolutely exhausting staying in the ACD.” ~ Public comment made by an Army spouse and mother of two children with autism at the April 12, 2024, public session

SOURCE: Committee generated from public input.

dosage) is defined as the number of hours per week an individual is directly engaged in receiving ABA services. This engagement includes direct face-to-face assessment as well as treatment services because the two are intertwined. In some studies, the amount of ABA received also includes services delivered by parents and other caregivers. In other studies or reviews, it may only include ABA services delivered by behavior analysts and technicians or other paraprofessionals. The time the behavior analyst spends on indirect assessment (reviewing notes and data and revising written plans) and on training caregivers is generally not considered a component of ABA intensity for a particular individual.

There appears to be no standard of reporting amount of ABA based on the committee’s review. Practices vary in regard to diagnosing professionals’ recommendations for ABA services for people with autism; many may not specify or consider what proportions of time will be spent on direct versus indirect services or caregiver training. In practice, even some ABA providers and payors may consider the amount of ABA to include all services encompassed by CPT and other billing codes. Others may adhere more closely to the published studies and separate the time the client is directly engaged in receiving assessment and treatment services from indirect assessment and caregiver training.

Many commercial plans cap the amount of ABA to 40 hours per week. The CASP guidelines offer that 30–40 hours per week of direct ABA is best for comprehensive ABA and that 10–25 hours per week may be appropriate for focused ABA (CASP, 2024). Current practice tends toward individualizing treatment intensity based on the time deemed necessary to make progress toward goals, and practice guidelines tend to recommend 25 or more hours of services generally, inclusive of ABA,

educational, allied health, and other services (National Research Council, 2001; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2015). Of note, a family’s ability to commit to receipt of services, availability of ABA providers, as well as benefit coverage available to them would play a role in amount of ABA actually received. The ACD does not put a cap on the amount of ABA received, but as reviewed in Chapter 6, the analyses of ACD data indicate that a significant proportion of the participants who receive ABA services receive less than 10 hours per week of ABA.

The standard practice of regularly evaluating progress toward goals (discussed below) is seen as a critical step for determining if the treatment intensity is serving the client and family well and whether the intensity should be adjusted.

Settings and Modality

Research shows that for most autistic individuals, ABA treatment needs to be delivered in multiple settings to enable behavior changes to generalize (carry over) from the primary treatment conditions to other places, times, people, and stimuli (Arnold-Saritepe et al., 2023; CASP, 2024; Falligant et al., 2021; Green, 2025; Rincover & Koegel, 1975; Waters et al., 2020). If ABA interventions are delivered outside of an autistic individual’s natural setting, provision of the services should plan for the generalized use of the skill being taught in other places, with other people, and/or in the presence of other stimuli. It may not be obvious to an individual with autism how to use new skills in other settings. As such, the delivery of ABA has developed in ways to be administered more often in real-world settings for best progress. Like other aspects of ABA services, the location (e.g., clinic, house, school, community setting) in which services are delivered are individualized to the client’s circumstances and can vary by session over the treatment duration. Some military families utilizing the ACD reported how limitations on settings have impacted their child’s treatment goals and ability to thrive outside the home. (These family perspectives appear in Box 4-4.)

Although ABA services are typically delivered in person, certain conditions may make telehealth delivery necessary or advantageous (e.g., for individuals residing in areas with no qualified providers nearby, during infectious disease outbreaks or natural disasters, for military families who need to retain services while transitioning to a new duty station).

The CASP standards specify that decisions about telehealth treatment need to be driven by clinical usefulness for the individual, treatment targets, the availability of resources and assistance necessary for safe and effective telehealth delivery of ABA services, applicable laws and regulations, and payor policies (CASP, 2024).

BOX 4-4

Perspectives on Treatment Settings

The committee’s information gathering included listening sessions and a call for public input to understand experiences with the ACD and ABA. While not meant to be representative and reflect the full range of perspectives or experiences of individuals and military families, this information provides important context for understanding the experience of those enrolled in the ACD and those receiving or providing ABA services, as well as the experience of those living with autism. This input served as a backdrop for the committee’s review and assessment of the available empirical literature, as well as a reminder of the real-life stories and experiences behind the data. This provided context for, though not the basis of, its conclusions and recommendations. This box presents some of the comments that the committee received regarding the 2021 ACD policy revision that limited the delivery of ABA services in the school and outside the clinic and home.

“We were no longer able to have our behavior analyst go with us to new medical appointments, and my son has extreme anxiety when seeing medical providers [. . .] Now I have to resort to sedating him basically so that someone can look in his ear and diagnose an ear infection.” ~ Public comment made by an Air Force parent at the April 12, 2024, public session

“My oldest son went into kindergarten in 2019 and we sent him to a school that allowed [. . .] his RBTs to go with him. By November, he didn’t need them anymore. But now that support isn’t even an option.” ~ Public comment made by an Army spouse and mother of two children with autism at the April 12, 2024, public session

“My son was using ABA in school because he was in private school [. . .] it was really helpful for him to have ABA service in there. They were able to focus on [. . .] the behavioral aspects of going to school. Once [DHA] pulled the aids, he was no longer able to go to school there anymore and we had to put him in public school. So, we had to completely change the venue in which he was able to go to school, which was really detrimental to him.” ~ Public comment made by a retired Army spouse and mother of four children with autism, at the April 12, 2024, public session

“Therapy in a clinic setting or in a home creates a false sense of security. Our hope is that they, our children, can function and be productive members of society, and that means allowing therapists inside their daycares and inside their schools where they’re spending much of their time so that we can effectively tackle what challenges they’re facing.” ~ Public comment made by an Air Force spouse and mother of an autistic child at the March 6, 2024, public session

“Our goals for each patient are part of generalization for mastery and success in multiple environments, yet we are rejected to community settings often. How are we to state that we have truly generalized goals with patients when we’re limited?” ~ Written comment to committee by ABA practitioner and parent of children with autism

“[T]here is difficulty with being approved to go into community settings and schools. I understand the purpose behind this restriction and agree that ABA providers are not aides in schools and are not babysitters. We, however, should be allowed to provide ABA services to target specific goals in the community and in schools. Right now, BCBAs are allowed to do this in schools. This should also be allowed by the RBT. As long as there are specific goals being targeted, it shouldn’t matter if it is done by a BCBA or RBT. In the community, we see difficulties for families in going to parks, restaurants, doctor offices, grocery stores, etc. These places should be approved to provide ABA as they are more likely to be where problem behaviors are occurring and where we are able to directly work on reducing those problems for the family.” ~ Written comment to committee by BCBA in Tennessee

SOURCE: Committee generated from public input.

Safety Measures and Crisis Management

Children with autism and intellectual and developmental disabilities are at increased risk for potentially harmful behaviors that can pose serious and immediate risk for injury for self and others (Farmer & Aman, 2011; Kurtz, Leoni, & Hagopian, 2020; McClintock, Hall, & Oliver, 2003; Simó-Pinatella et al., 2019; Soke et al., 2016; Steenfeldt-Kristensen, Jones, & Richards, 2020; Wachtel et al., 2024).15 Synthesized data from 37 studies of autism yielded pooled prevalence estimate of self-injury of 42% (Steenfeldt-Kristensen, Jones, & Richards, 2020). A recent study showed that among children with profound autism, nearly 37% had self-injurious behavior (Hughes et al., 2023); another found that children and adults with autism were three times more likely to self-harm than people without autism (Blanchard et al., 2021).

Restraints of various kinds are sometimes used in situations where an autistic child engages in behaviors that can lead to self-harm and harm to others. Before discussing restraints and their use, it is important to note that proper training is essential for the safe and compassionate use of restraints in crisis situations. In 2010, the ABAI published a statement on restraint and seclusion outlining guiding principles and the careful application of

___________________

15 Potentially harmful behaviors can include (a) self-injurious behavior such as head-banging, head hitting, self-biting, and self-scratching; (b) aggressive and disruptive behaviors that can result in severe injuries to family members and staff; (c) pica (the ingestion of nonedible items); and (d) elopement (leaving a supervised area without caregiver knowledge) that can result in injury or death (Anderson et al., 2012; Dekker et al., 2002; Farmer & Aman, 2011; Sturmey, Seiverling, & Ward-Horner, 2008).

crisis prevention procedures.16 Many other national training and certification programs for crisis prevention teach proactive and compassionate crisis prevention techniques. Such programs include Safety-Care,17 Crisis Prevention Institute (CPI),18 and Marcus.19 These certification/training programs are also utilized by emergency response, law enforcement, mental health, and educational professionals.

When used in the context of a behavior intervention plan, specific crisis management and safety measures can serve to reduce risks of injury to autistic children, family, and care providers and can facilitate learning opportunities that support positive behavior. According to guidance on crisis management, the application of restraints or seclusion need to be implemented according to well-defined, predetermined criteria; include the use of de-escalation techniques designed to reduce the target behavior without the need for physical intervention; be applied only at the minimum level of physical restrictiveness necessary to safely contain the crisis behavior and prevent injury; and be withdrawn according to precise and mandatory release criteria (Vollmer et al., 2011). Guidelines stress the importance that the comprehensive treatment or safety plan only include restraint or seclusion with the consent of the individual and parents or guardians after informed of the methods, risks, and effects of possible intervention procedures, which include the options to both use and not use restraint (Vollmer et al., 2011).

Several types of restraints have been deemed appropriate to use, with proper training and oversight, in certain situations. These types of restraints include the following:

- Physical Restraints: Holding or hugging the person, using a vest or jacket, or covering the person’s hands or feet to reduce the risk of injury.

- Mechanical Restraints: Chairs with safety belts, seclusion rooms, or special beds.

- Pharmacological Restraints: Medications used to calm or sedate the person.

When utilized correctly and delivered in a compassionate and dignified manner for the client, crisis intervention techniques such as the above can provide necessary safety measures when the client and/or provider are in

___________________

16 For the full statement, see https://www.abainternational.org/about-us/policies-and-positions/restraint-and-seclusion,-2010.aspx

17 For more information about the Safety-Care Crisis Prevention Training program, see https://qbs.com/safety-care-crisis-prevention-training/

18 For more information about the CPI, see https://www.crisisprevention.com/

19 For more information about Marcus, see https://www.marcus.org/autism-training/crisis-prevention-program

imminent danger of harm (Linn, 2024). When crisis management or restraints are prohibited, as with the ACD, beneficiaries who have aggressive and/or self-injurious behaviors can be limited in their access to care.

Alternatives to restraints exist, and these too can be used as safety measures in cases of harm to self or others. These alternatives are longer-term approaches but, when incorporated into treatment, have been shown to be effective strategies at moments of crisis. Alternatives to restraints include the following:

- Positive Behavior Support: Using strategies to prevent and manage challenging behaviors through positive reinforcement and environmental modifications.

- Sensory Integration Therapy: Providing sensory experiences to help the person regulate their emotions and behaviors.

- Communication Training: Teaching the person effective communication skills to express their needs and reduce frustration.

The use of restraint techniques is excluded from reimbursement under the ACD and is included under a broader category of “aversive techniques” (DHA, 2023a, section 8.9.8.1). As such, ABA providers are prohibited from using restraint techniques without exception, including safety measures that would prevent self-harm from occurring to the child receiving ABA. In the absence of such crisis management techniques, ABA providers are expected to utilize other behavior analytic approaches to develop their behavior management plans for children who may be likely to self-harm (DHA, 2021e). While DHA does not have a specific definition of restraints that it uses in this policy, it refers to a common definition: “Restraint is any manual method, physical or mechanical device, material, or equipment that immobilizes or reduces the ability of an individual. Types of restraints include: prone, supine, physical, mechanical, and chemical restraints, as well as aversive interventions” (DHA, 2021a, pp. 3–4). Additionally, DHA cites the Joint Commission standards on the usage of restraints in its rationale, which “stresses minimal usage, implementing the intervention as an absolute last resort, and ensuring all staff are adequately trained regarding the application of restraints” (DHA, 2021a, p. 4).

The Joint Commission recently published new and revised restraint and seclusion requirements for behavioral health care and human services organizations in June 2024 that include updated requirements for children and youth. In addition to other protocols for the safe and limited use of restraints, the Joint Commission standards promote written policies and procedures, training to ensure necessary competencies for licensed practitioners and other staff, assessment and treatment planning to minimize use, limiting use to situations of imminent risk of harm, notifications to the clients and

their families on polices regarding use of restraints and safety measures, and additional staff for monitoring when used (The Joint Commission, 2024).

Tiered Delivery and Staffing

There are two types of tiered models for the delivery of ABA services by provider teams: the two-tiered model and the three-tiered model (CASP, 2024). In the two-tiered model, one or more behavior technicians deliver services to clients under the direction and supervision of a professional behavior analyst—a BCBA, BCBA-D, or someone with similar training. The behavior analyst is responsible for managing or supervising all aspects of each client’s case: designing assessment and treatment plans and procedures, training the technicians and caregivers (where applicable) to implement the procedures, analyzing client data frequently, modifying treatment plans and protocols as needed, collaborating with other providers, and communicating with clients, caregivers, and payors. The technician, in this model, is responsible for implementing assessment and treatment protocols as assigned by and under the close oversight of the supervising behavior analyst.

The three-tiered model adds a mid-level team member—a BCaBA or someone with similar training, if allowed by law or payor policies—who assists the behavior analyst with training and supervision of technicians and may perform other duties under the supervision of the behavior analyst, such as case supervision, assessing and treating clients, reviewing data, developing protocols, and training caregivers. The CASP standards recognize that higher ratios (e.g., two ABA providers to one client) may be necessary implement assessment and/or treatment protocols for behaviors that are dangerous to the client or others (CASP, 2024).

For both models, the CASP standards specify that the behavior analyst be familiar with the client’s characteristics and treatment plan, ensure that all team members are competent to perform responsibilities assigned to them, and observe them implementing the treatment plan regularly (CASP, 2024). These standards also require all practitioners to operate within the profession’s scope of practice and their individual scope of competence, and to comply with standards (e.g., ethics, supervision requirements) specified by the profession and applicable laws and regulations. See Figure 4-2 for an illustration of the tiered delivery model.

Evaluation of Progress

Measuring progress with ABA services is complex, since there is an imprecise relationship between treatment and outcomes on behavior and health. Many factors can affect outcomes. Nonetheless, regular assessment and selection of measures to track individuals’ progress are key components

NOTE: BCaBA = Board Certified Assistant Behavior Analyst; BCBA = Board Certified Behavior Analyst; BCBA-D = Board Certified Behavior Analyst, Doctoral Level; RBT = Registered Behavior Technician.

SOURCE: CASP, 2014.

of ABA. Assessments in standard practice often are customized toward clients’ goals and draw on multiple sources of data including direct observations and measurements of behavior, review of clients’ medical history, interviews, and the administration of standardized instruments (CASP, 2024).

Many standardized assessment instruments have been developed for autistic individuals or for behaviors that might be addressed by ABA. However, they are not equivalent in purpose or use. There are even standardized instruments for collecting data on caregivers, their satisfaction with ABA services, as well as indicators of family well-being. Behavior analysts are encouraged to consult with other professionals before determining which instrument(s) are appropriate for particular clients and their families, to select instruments with domains and items that will inform treatment goals, and to use results from standardized instruments in conjunction with data from other sources in assessing an individual’s progress (CASP, 2024). Assessment tools have changed over the past 10 years and continue to evolve and advance as understanding of autism changes and improves.

This is a very heterogeneous population ranging from individuals with high intelligence and good communication skills to those with major cognitive impairment and those who never developed language. Individuals at all levels of communication and cognitive ability also vary on the range and intensity of restricted and repetitive behavior and the level of impairment caused by sensory sensitivities. One specific assessment tool or set of tools will not be appropriate to obtain the information needed to develop an appropriate treatment plan or evaluate progress for every autistic individual.

A combination of standardized assessments that are direct (administered to the client or patient) and some that are indirect (completed by caregivers or other third parties) is preferred. Selection of standardized assessments would need to be guided by the characteristics of the instrument and the individual’s presenting conditions and support needs. Standardized assessments provide guidance in overall cognitive and adaptive level but not enough detail to develop a treatment plan. Non-standardized assessments, such as curriculum assessments, language sampling techniques developed by speech pathologists, and adopted procedures for direct observation and recording of behaviors, are common in delivery of ABA. Such assessments are often accompanied by procedures to determine the accuracy and reliability of human observations. They are used to develop specific measurable goals and to choose the most appropriate strategies to address those goals as well as the intensity of intervention needed. Furthermore, progress toward these measurable goals can be tracked to understand individual progress more accurately than standardized assessments.

A functional behavior assessment is a particular type of behavior analytic assessment to identify environmental events that influence challenging behaviors. Those data can be graphed and reviewed and updated frequently throughout services. This type of assessment is typically the main source of

data that behavior analysts use to modify treatment procedures for challenging behaviors and to determine client progress (Horner & Carr, 1997).

Any instruments or assessment tools chosen need to have good psychometric properties, including good reliability and validity, and appropriate norms (where relevant). Ideally, decision support and other practical considerations (online administration, automated scoring, etc.) are available to ABA providers to help with administering the tools and interpreting assessment information, particularly for standardized norm-referenced assessments (Frazier, 2024). In addition, the tool’s sensitivity to track change is important. There are best practices (e.g., growth scale values or growth scores, reliable change indices, decision support for identifying when behaviors have returned to the neurotypical range) that are available for some instruments and not others that facilitate appropriate change detection during intervention. However, because of the heterogeneity among autistic individuals, change detection and expectations for change need to be adjusted for the phenotypic profile (cognitive level, symptom severity, adaptive function deficits, presence of challenging behavior) of the individual. Expecting the same level of change from all individuals is not reasonable and not consistent with the published literature (Frazier et al., 2021).

Most commercial payors encourage regular assessment and reauthorization at six-month intervals; however, they do so without mandating which tools to use. The ACD requires all ABA providers to periodically administer four specific standardized assessment instruments; this is in addition to assessments that ABA providers would normally select to track clients’ progress and extra responsibilities those providers serving families participating in the ACD have. See further discussion of the ACD requirement of periodic assessments in Chapters 6 and 7.

Billing and Reimbursement Exclusions

Billing for ABA services is a complex process. Payors continue to develop their policies and rules as the field evolves and as legislation and regulations change, and currently, requirements vary among payors. While having to adjust to differences in payor policies in the delivery of medical care is not unique to ABA services, ABA providers have expressed challenges in targeting critical health goals because of particular restrictions, notably those administered through the ACD.20

There are several groups working on educating payors and ABA providers about reasonable billing practices for ABA (e.g., ABA Coding

___________________

20 The committee heard perspectives from ABA providers at its public information gathering sessions. Find details of past events here: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/independent-analysis-of-department-of-defenses-comprehensive-autism-care-demonstration-program#sectionPastEvents

Coalition and National Correct Coding Initiative). The committee was not charged to examine billing, and a comprehensive review of coverage policies and billing practices for ABA was beyond the scope of this study. However, during its review of the ACD, the committee heard often about ACD billing restrictions that do not adhere to industry guidelines or practices and are likely affecting access to quality care. These highlighted restrictions include the following:

- Limited authorization of CPT codes that can be billed under the ACD. CPT codes specifically excluded include 97152, 97154, 0362T, and 0373T (see Box 4-2 for code descriptions).

- Limited authorization of CPT code 97155. This code can only be used for 1:1 ABA delivery by professional behavior analyst and not for time spent by behavior analyst supervising a technician delivering ABA.

- Restriction on concurrent billing of 97155 and 97153.

- Utilization expectations of 97155 and 97156 exceed common standards of care.

- Restriction on reimbursement of technician time working toward their 40-hour training requirement for certification.

As a result of these restrictions, care can be constrained. For example, concurrent billing for a technician and a behavior analyst at times is essential for professional supervision of the technician’s administration of ABA; this supervision ensures quality and addresses areas for improved implementation as outlined in the CASP guidelines (CASP, 2024). Concurrent billing of the technician and the ABA supervisor is an expected component of the AMA CPT codes (ABA Coding Coalition, 2022).

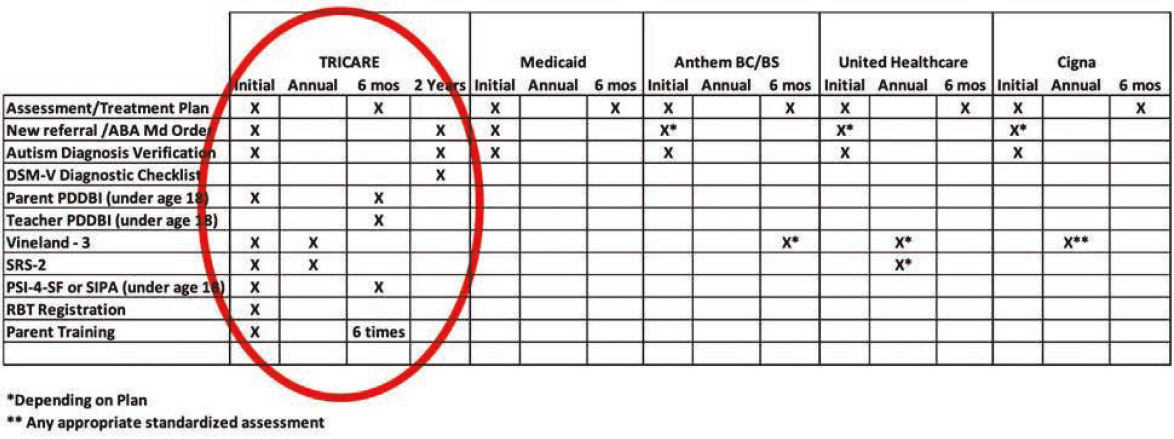

According to the ABA providers who presented to the committee, working with the ACD and TRICARE has meant that documentation requirements are more onerous, non-payment of services is common (i.e., claims denied more frequently), and recoupment of services for technical errors is more common in comparison to what is experienced with other payors (Linn, 2024; NASEM, 2024a; Sims, 2024; Thompson, 2024; Waters, 2024). These billing limitations and exclusions are just part of the administrative challenges experienced by ABA providers in serving TRICARE clients and reported to the committee. Other challenges, such as administration of multiple assessments and parenting stress indices and parent training requirements, are discussed elsewhere in this chapter and throughout the report. One provider shared a table of the added burdens that apply to TRICARE’s plan compared to others (see Figure 4-3).