The Comprehensive Autism Care Demonstration: Solutions for Military Families (2025)

Chapter: 5 Evidence Base for Applied Behavior Analysis

5

Evidence Base for Applied Behavior Analysis

This chapter provides an orientation to the evidence around applied behavior analysis (ABA) and its application with autistic individuals. The chapter begins with a brief definition of what ABA is and, importantly, what it is not. The subsequent examination of the evidence for strategies grounded in ABA includes a review of health outcomes, discussion of an umbrella review of meta-analyses of comprehensive ABA-based programs that was commissioned by the committee, and a systematic review of meta-analyses of focused intervention behavioral practices. Finally, the chapter takes up an implementation science perspective and discusses factors that would affect delivery of ABA services to autistic individuals and their families that may be relevant to the Military Health System.

DEFINITION AND DIMENSIONS OF APPLIED BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS

ABA is the use of single behavioral practices (e.g., reinforcement, prompting) or combinations of behavioral practices (e.g., functional communication training [FCT], naturalistic intervention) to promote socially important health and behavioral outcomes. At the outset of this chapter, the committee wishes to flag the importance of addressing the common misperception that ABA is one practice. The Defense Health Agency (DHA), in its reports to Congress, often characterized ABA as one practice or one comprehensive early intensive behavioral interventional (EIBI). As this chapter describes, this is not an accurate description of ABA. ABA is in fact a set of different intervention practices grounded in the science of learning. Therapists, clinicians, and other trained professionals employ ABA practices

to address autistic individuals’ personalized learning, behavioral, and health goals. Program developers sometimes establish a guiding conceptual framework to organize the focused intervention practices into formal comprehensive programs. Focused intervention practices and comprehensive programs are discussed further in subsequent sections.

Although a large proportion of Comprehensive Autism Care Demonstration (ACD) participants are young children, that does not necessarily mean that they are receiving or should receive an EIBI program. Other ABA practices can be provided to both younger and older autistic individuals whose needs would better be addressed by them.

Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1968) identified seven defining “dimensions” of an ABA conceptual framework, which have guided the field for most of its history. These defining features are as follows:

- Applied—socially important rather than only theoretically relevant

- Behavioral—objective outcomes rather than hypothetical constructs

- Analytic—believable demonstration of intervention effects

- Technological—clearly identified and described procedures

- Conceptually systematic—reflects behaviorist orientation

- Effective—outcomes large enough to be of practical value

- Generality—effects are durable over time, appear in a variety of environments, and/or are reflected in a variety of behavior changes

Elaborating on these dimensions, Wolf (1978) introduced the concept of social validity, proposing that individual goals, program practices, and program outcomes should be meaningful and have real-world importance for individuals and family members affected by the program. Contemporary researchers have proposed compassion (i.e., empathy and action) as an additional core dimension (Penney et al., 2023).

APPLIED BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS AND AUTISM

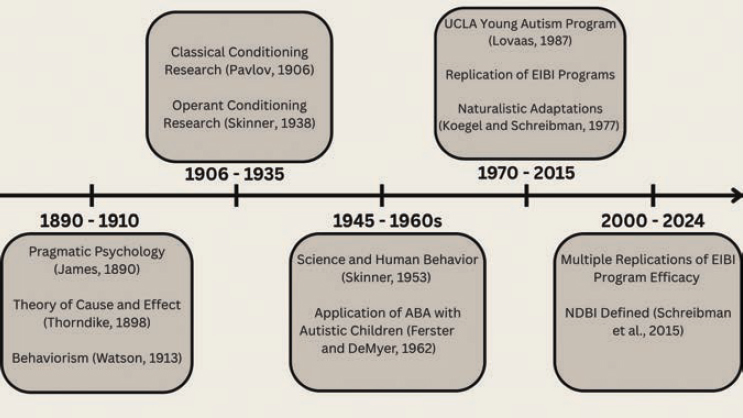

The roots of ABA extend back more than a century to the early pragmatic psychology of William James (1890), E. L. Thorndike’s (1898) theory of cause and effect, and the early behavioral psychology of J. B. Watson (1913) (see Figure 5-1 for a timeline). Both Pavlov’s classical conditioning research (1906) and Skinner’s operant conditioning research (1938) provide the basic laboratory research, which Skinner extended to application with humans in the 1950s (Skinner, 1953).

Researchers’ application of applied behavioral practices with young autistic children in particular began in the 1960s (Ferster & DeMyer, 1962). The application of ABA in a comprehensive program began with Lovaas’s

influential research (Lovaas et al., 1973) that led to the establishment of the UCLA Young Autism Program, with some evidence of efficacy (Lovaas, 1987). Though valid concerns arise in discussion of Lovaas’s approach and some of the intended outcomes of application of ABA within these clinics (Leaf et al., 2022), this program became the catalyst for subsequent EIBI programs commonly used today (Rue, 2024). Currently, many ABA agencies conducting EIBI use a highly structured set of strategies, Discrete Trial Training (DTT), as the primary comprehensive strategy for a majority of clients. Autistic adults have raised concerns regarding the ethics of traditional DTT approaches that focus on compliance, on suppression of characteristically autistic behaviors, and on “curing” autism, fearing that such approaches pathologize autism and, anecdotally, may cause harm to autistic people (e.g., Chapman, 2021). While views vary widely, many neurodiversity advocates support person-centered, respectful EIBI with a focus on skill building and improving quality of life (den Houting, 2019).

The work of Koegel and Schreibman (Koegel & Koegel, 1987; Koegel & Schreibman, 1977) adapted the features of Lovaas’s program to focus on pivotal behaviors addressed in naturalistic contexts. Their work and that of others in the field (Rogers et al., 2012) led to a recognition of some ABA services as naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions (NDBIs) (Schreibman et al., 2015).

NDBIs combine developmental science with ABA to include developmentally appropriate teaching strategies that promote integration of

learning into daily activities to build well-generalized application of learned behaviors. Additionally, these practices respect an individual’s interests, choices, and initiative, and focus on their own motivations to support client-directed learning. NDBIs, when done well, utilize a child-driven, strengths-based approach that supports the child-environment fit. NDBIs fully qualify as ABA (Vivanti & Stahmer, 2021) and have great potential to better align early ABA intervention with the goals of autistic individuals (Schuck et al., 2021).

Research Methodology and Evidence Standards

Practices that promote health outcomes for autistic individuals are based in a variety of professional disciplines that sometimes have different perspectives on what research methodology serves as acceptable evidence of efficacy and effectiveness. From the medical community, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are often stated as the “gold standard” research methodology (Hariton & Locascio, 2018), although not without criticism (Cartwright, 2007). While ABA researchers have applied RCTs for evaluations of comprehensive programs, they have also used a different experimental methodology called single-case design (SCD) to examine efficacy of focused intervention practices. Because this methodology is either unknown or misunderstood by some members of the medical and healthcare community, it is important to briefly describe the methodology and the evidence provided by SCD studies.

SCDs are based on replications of ABA practice effects (e.g., increases in starting a conversation, decreases in self-injurious behavior) within or between study participants (Kazdin, 2021). These effects are demonstrated by first repeated assessment of a target behavior (e.g., communication or self-injurious behavior) before an intervention practice (e.g., FCT) is initiated, and then examining changes in the target behavior during and after practice implementation. Threats to internal validity (e.g., history, maturation) are controlled by subsequent withdrawal and re-implementation of the practice within participants or the delayed onset of the practice across participants. SCD studies rarely include only one participant, so experimental effects are usually demonstrated/replicated across participants. There are, however, usually a small number of participants in an SCD study, so concerns about the external validity of a single study are legitimate. Evidence for an ABA practice is built through systematic replications of SCD studies of that identified practice by different research groups (Horner et al., 2005) and through meta-analyses of those replications (Jamshidi et al., 2022). Rigorous SCD studies have been recognized by multiple professional organizations and academic journals as a scientifically valid methodology for evaluating treatment effects (Aydin, 2024; Kratochwill et al., 2010; Rodgers et al., 2018).

Applied Behavior Programs and Practices

In the application of behavior analysis for autistic individuals, there are two classifications of interventions: focused intervention practices and comprehensive programs. Focused intervention practices are single or combinations of individual ABA practices that focus on a single or a set of individual outcomes. Comprehensive programs are a combination of practices designed to produce broader developmental and learning outcomes.

Focused Intervention Practices

ABA practitioners employ focused intervention practices to address individual goals and behavioral or developmental outcomes for autistic individuals. These may be single practices, like reinforcement, prompting, time-delay fading of prompts, or functional assessment. Or, they may consist of a combination of individual practices employed in a coherent and planned way. For example, FCT is designed to promote communication and subsequently reduce interfering behavior. FCT consists of four foundational focused intervention practices: (a) functional assessment, (b) antecedent interventions, (c) extinction or ignoring undesired behavior, and (d) differential reinforcement of alternative behavior.

Researchers with the National Clearinghouse on Autism Evidence and Practice (NCAEP) have identified a set of focused practices that have sufficient single-case and group design evidence of efficacy to be classified as evidence-based (Hume et al., 2021; Steinbrenner et al., 2020). This group identified 28 evidence-based practices, of which 20 have an ABA origin. This is an important point because, as noted previously, laypersons or professionals without training in or knowledge of ABA often only equate ABA with singular applications of prompting, reinforcement, and/or DTT, whereas in reality, the procedural variety is much greater.

Comprehensive Programs

Comprehensive programs consist of practices organized around an ABA conceptual framework. They tend be employed for an extended period of time (nine to 12 months or more), address many individual goals that would lead to broader developmental and learning outcomes, tend to occur 10–20 hours or more per week, and often include family members (see Odom et al., in press). Comprehensive programs may follow EIBI and/or NDBI approaches. Examples of ABA-based comprehensive programs are Pivotal Response Treatment (PRT), Early Start Denver Model (ESDM), Alliance for Scientific Autism Intervention (formerly Princeton Child Development Institute model; Townsend et al., 2023), and LEAP (Learning Experiences

and Alternative Program for Preschoolers and their Parents). Although the majority of the comprehensive programs have been designed for young autistic children enrolled in clinical or home settings, there are examples of programs specifically designed for older individuals located in schools (Anderson et al., 2021; Hume et al., 2021; Odom et al., 2021; Stahmer et al., 2023; Suhrheinrich et al., 2022) and vocational settings (Wehman et al., 2020). Many of these programs have evidence of efficacy provided by RCTs or quasi-experimental design studies (Odom et al., in press).

EVIDENCE FOR EFFICACY

Part of the committee’s statement of task is to conduct a “review of health outcomes, including mental health outcomes, for individuals who have received applied behavior analysis treatments over time” (see Chapter 1, Box 1-3). This review is meant to address concerns raised by DHA around ABA’s efficacy and does not provide a comprehensive review of other interventions that may also be effective with this population. In multiple reports to Congress and in responses from DHA to this committee, a consistent message has been that ABA services lack sufficient evidence of efficacy to be covered as a TRICARE Basic benefit. In its most recent report to Congress, DHA stated that the agency’s “final benefit determination concerning the status of ABA will be informed by the results of a pending Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program study; the National Academies [of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine] analysis; the analysis of program and clinical outcomes from the ACD; and the state of other available reliable evidence, such as new research findings on the efficacy of ABA based on well-controlled studies with clinically meaningful endpoints published in peer-reviewed research journals” (DoD, 2024a, p. 8).

To address the charge to examine health outcomes, it was important for the committee to agree on a working definition of health outcomes. The committee adopted the definition provided by Lamberski (2022): “A health outcome refers to both physical and psychological well-being and takes into account the length of life as well as the quality of life” (p. 1). Examples of such outcomes include improvement in cognitive skills (i.e., which reflect a broad range of problem-solving in daily life), social communication, activities of daily living and other adaptive skills, sleep disorders, reduction and replacement of challenging behaviors (e.g., self-injurious behaviors, meltdowns), as well as amelioration of depression, anxiety, and other negative mood states. Such outcomes, as well as others that address physical and psychological well-being, may well be viewed as outcomes for ABA services. This definition provides context for the committee’s review of the evidence and outcomes of ABA, which included a commissioned meta-analysis review of ABA comprehensive programs as well as a systematic review of focused intervention practices (see details below).

Basing research evidence for therapeutics and interventions on systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the empirical literature is a valid method that follows guidance from the evidence-based practice framework. This framework is commonly used to inform treatment decision making in clinical practice. In 1996, Sackett provided a definition of evidence-based medicine (EBM) that is still in use today: “Evidence based medicine is the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research” (Sackett et al., 1996, p. 71).

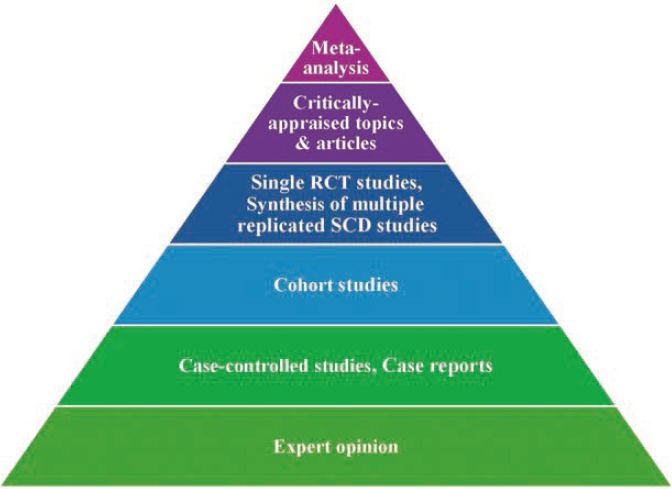

Sackett’s work on EBM also expanded the levels of evidence hierarchy (Sackett, 1989). The levels of evidence hierarchy in medicine are often visually depicted as a pyramid with meta-analyses and/or systematic reviews at the top of the pyramid and representing the highest form of evidence (consistent with the commissioned report on ABA services) and case series studies or reports involving no comparison group often at the bottom. Note that case reports are distinguished from SCD studies described previously. The latter includes experimentally controlled replication of treatment effects and ranks higher (as shown in Figure 5-2). In social and behavioral science research, the top of the pyramid remains the same; however, the bottom of

SOURCE: Adapted by the committee from Aldous et al., 2024.

the pyramid may reflect qualitative research, correlational studies, and/or expert opinion.

The Cochrane Collaboration and Campbell Collaboration are two well-known international organizations involved in the quality appraisal of clinical research, with the former more involved in healthcare research and the latter in social and behavioral science research. Both organizations produce meta-analytic syntheses of empirical research. The committee drew upon the quality standards and methods used by those groups for its commissioned paper to examine the state of the evidence for ABA-based interventions for young children with autism.

Commissioned Paper on State of Evidence for Comprehensive ABA Services for Autism

As noted previously, comprehensive ABA programs for young children have followed both early EIBI or NDBI models. Reviews of meta-analyses, or umbrella reviews (Belbasis, Bellou, & Ioannidis, 2022), can help to evaluate what type of evidence is available. As of this writing, the most current review of previous meta-analyses of NDBI programs was recently published by Song, Reilly, and Reichow (2024). To provide a similar review for EIBI and other ABA programs, the committee commissioned one of the authors of that NDBI review to conduct an up-to-date umbrella review that evaluated the state and quality of the empirical evidence on EIBI and other ABA-based comprehensive interventions for autistic children (Reichow & Barton, 2024). For these reviews, the authors used the following parameters to define comprehensive ABA-based interventions: “a) manualized treatment based on the technologies of applied behavior analysis and the science of human behavior; b) high intensity, as defined by 10 or more (on average) hours of treatment per week; c) longevity, as defined by a treatment duration (on average) of at least 6 months; and d) comprehensive, as defined by the treatment of at least two different developmental domains” (Reichow & Barton, 2024, p. 7). The commissioned report is entitled Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Comprehensive Applied Behavior Analytic Interventions for Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. The committee noted that there is no overlap of meta-analysis studies included in the umbrella meta-analysis by Song, Reilly, and Reichow and that by Reichow and Barton.

Umbrella Review of EIBI and Other ABA Comprehensive Programs

The committee’s commissioned umbrella review on EIBI programs by Reichow and Barton examined six meta-analytic reviews of comprehensive ABA services for children under nine years of age. The six reviews included studies that used either RCTs or quasi-experimental designs. There was a

total of 73 individual studies included from the six meta-analytic reviews (range five to 20 studies per review), and across those studies, a total of 2,241 children, with the majority being male (84.8%). It should be noted that there is study and participant overlap across the six reviews; however, the commissioned authors, Reichow and Barton, assessed various risks of bias, including overlap of primary studies. The most common group comparative conditions across studies were treatment as usual or eclectic intervention approaches.1

The primary outcomes of interest for the umbrella review were changes in cognitive ability (i.e., IQ) and adaptive behavior (i.e., “conceptual, social, and practical skills that all people learn in order to function in their daily lives”; American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 2025) because those were consistently measured across studies. Secondary outcomes included communication (i.e., functional or everyday use of communication and language), expressive language, receptive language, socialization, daily living skills, and autism characteristics. Primary and secondary outcomes were measured using standardized assessments that are routinely used in autism research. Further, measured outcomes reflect core features of autism (e.g., communication, socialization) and co-occurring conditions (e.g., IQ). Within the commissioned report, standardized mean difference (SMD) or mean difference (MD) effect size estimates were reported based on which effect size metric was included in each of the included six meta-analytic reviews. For SMD, a common rule of thumb is that effects sizes of .20 and below are considered small, .50 moderate, and .80 large (Cohen, 1988). The sizes of MD are interpreted relative to the mean of the instrument and expectations of growth. For IQ, three meta-analyses used SMD and three used MD. SMD effect sizes for IQ ranged from .50 to greater than .80, and MD effect sizes for IQ ranged from 7.5 to greater than 12.0. For adaptive behavior, SMD ranged from .20 to .80 and MD ranged from 3.0 to 12.0. Overall, effect sizes for the primary outcomes of cognitive ability and adaptive behavior were positive and primarily in the moderate to large range, especially for IQ.

For secondary outcomes, effect sizes were more modest and mixed, yet positive, for the outcomes of generalized communication skills (SMD range .30–.38, MD range 10.44–11.22), receptive language (SMD range .42–.55, MD = 13.94; only one study reported MD), expressive language (SMD range .46–.51, MD = 15.21), and daily living skills (SMD = .183, MD range 5.49–7.77). While outcomes also were positive for social skills and autism characteristics, they were not considered clinically significant

___________________

1 Eclectic approaches are those that usually provide the same number of hours of service (i.e., intensity) but employ practices from a variety of theoretical perspectives including, but not exclusively, ABA.

SOURCE: Reichow & Barton, 2024.

effects (see Figure 5-3 for primary outcomes and Figure 5-4 for secondary outcomes). Of relevance, outcomes are positive for the primary outcome of adaptive behavior and the secondary outcome of daily living skills, thus demonstrating that comprehensive ABA is frequently used to target and effective at improving those health outcomes for the autistic population.

Overall, the comprehensive ABA evidence indicates positive effects on targeted outcomes. The methodological approach of an umbrella review was used to synthesize existing meta-analyses of comprehensive ABA interventions. This allowed the best available evidence on comprehensive ABA to be identified—as one such indicator, all primary studies included in the umbrella review were controlled trials. Evidence from individual studies needs to be interpreted with some caution because of various risks of biases to conducted studies, which could include such issues as small sample sizes, lack of randomization, and use of single blind trials. It should be noted that these methodological issues are not specific to comprehensive ABA interventions as many of these same issues affect the study of other autism interventions (Sandbank et al., 2020).

NDBI Umbrella Review

The EIBI review above employed similar methodology as the umbrella review of NDBI meta-analyses mentioned above, conducted earlier in 2024 by Song, Reilly, and Reichow (2024). That review included five meta-analyses, two on ESDM, two on PRT, and one on general NDBI studies (not specifying by specific program type). A total of 66 studies (i.e., 48 unduplicated) was included across the meta-analyses, involving a total of 1697 participants. The authors reported a high risk of bias for the areas of synthesis and findings and low risk of bias for study eligibility, data collection, and appraisal. SMDs were most often reported as Hedges g, the magnitude of effect size interpreted in generally the same way as Cohen d

SOURCE: Reichow & Barton, 2024.

(e.g., low = < .20; high = > 80). The meta-analyses revealed positive mean effects for the cognitive (g = .15–.41) and communication (g = .20–1.2) domains, with small effects for adaptive (g = .12–.31), autism symptomatology (g = −6.30–.05, lower is more positive score here), and restricted and repetitive behavior (g = −0.01–.20).

State of Evidence for ABA Focused Intervention Practices

As described earlier in this chapter, focused intervention practices are the individual components within comprehensive ABA programs and often the “building blocks” that behavioral therapists use to develop individualized services for autistic individuals. Unlike research on comprehensive

programs, which has focused primarily on young autistic children, the evidence for focused intervention programs extends through adolescence and beyond. In addition, the research literature on focused intervention practices also differs from the comprehensive program literature in that it primarily consists of SCD studies (Kazdin, 2021).

Given the medical field’s consensus that meta-analyses are the highest form of evidence, the committee conducted a separate umbrella review of meta-analysis studies that examined focused intervention practices targeting a variety of outcomes for autistic individuals across ages. In a previous systematic review, the NCAEP (Hume et al., 2021; Steinbrenner et al., 2020) identified 28 focused intervention practices. The committee reviewed the set of practices and determined that 21 were ABA practices.

Meta-analyses of group and single-case experimental design studies were found for 10 focused intervention practices: direct instruction, DTT, FCT, naturalistic interventions, parent-implemented interventions, peer-based interventions, prompting, reinforcement, self-management, and video modeling (see Table 5-1). Across these practices, 65 meta-analytic reviews were identified with the ages of participants ranging from 1 to 55 years. The study authors reported a variety of SCD effect size analyses, which included non-parametric (e.g., Tau-U) and parametric (e.g., use of multilevel models) effect estimates. Reported outcomes fell into the categories of either (a) significantly improving or increasing skills in the academic, social, communication, adaptive behavior, and vocational domains as well as school readiness and quality of life; or (b) decreasing interfering or challenging behaviors. In summary, positive effects were found across a wide range of outcomes, ages, and focused intervention practices (see Table 5-1), demonstrating the breadth of evidence for ABA-based services for autistic individuals when inclusive of both comprehensive and focused interventions.

Meeting TRICARE Hierarchy of Reliable Evidence Standard

In the 2024 report to congress, DHA concluded that “[a]s of now, ABA does not meet the TRICARE hierarchy of reliable evidence standard for proven medical care” (DoD, 2024b, p. 7). The TRICARE definition of reliable evidence, as defined in 32 C.F.R. § 199.2 states, “[T]he term reliable evidence means only:

- Well-controlled studies of clinically meaningful endpoints, published in refereed medical literature.

- Published formal technology assessments.

- The published reports of national professional medical associations.

- Published national medical policy organization positions.

- The published reports of national expert opinion organizations.”

TABLE 5-1 Focused Intervention Practice Definitions, Number of Meta-analyses, and Type of Outcome

| ABA Practice | Definition | # of Meta-analyses | Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Instruction | A systematic approach to teaching using a sequenced and scripted instruction, independent client responses, and error corrections to promote mastery and generalization. | 1 | Academic |

| Discrete Trial Training | A teaching approach that breaks down complex skills into smaller steps, using repeated trials, client’s response, and carefully planned positive consequences. | 2 | Communication/Language |

| Functional Communication Training | A set of practices aimed at replacing challenging behaviors with more appropriate and effective communication behaviors or skills. | 2 | Communication/Language, Maladaptive Behavior |

| Naturalistic Interventions | Strategies that embed learning in client’s typical activities and routines, often using client’s key interests. | 7 | Communication/Language, Play, Adaptive Behavior, Social, Quality of Life |

| Parent-Implemented Interventions | Training directed at caregivers to support their delivery of practices during daily lives to further advance skill development and limit challenging behaviors. | 19 | Social, Adaptive Behavior, Maladaptive Behavior, Communication/Language, School Readiness |

| Peer-based Interventions | Strategies and structured contexts directly involving peers to promote social interactions and/or other individual learning goals among autistic individuals. | 10 | Social, Academic, Communication/Language, School Readiness |

| Prompting | Strategies involving physical assistance or cues (verbal or gestural) to guide clients in engaging in targeted behaviors or skills. | 2 | Academic, Communication/Language, Vocational |

| ABA Practice | Definition | # of Meta-analyses | Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reinforcement | Strategies involving consequences following clients’ use of skills or behaviors designed to increase the likelihood of use in the future. | 3 | Communication/Language, Maladaptive Behavior |

| Self-management | An approach to instruction aimed to promote independence by focusing on client’s ability to discriminate between appropriate and inappropriate behaviors, monitor their own behaviors, and reward themselves. | 4 | Academic, Adaptive Behavior, Communication/Language, Social |

| Video Modeling | A teaching method that uses video-recorded demonstration of targeted behaviors or skills, allowing clients to observe and imitate actions. | 15 | Academic, Adaptive Behavior, Communication/Language, Social |

SOURCE: Modeled after Steinbrenner et al., 2020 (Table 3.1).

Further, the definition states that “the hierarchy of reliable evidence of proven medical effectiveness, established by (1) through (5) of this paragraph, is the order of the relative weight to be given to any particular source. With respect to clinical studies, only those reports and articles containing scientifically valid data and published in the refereed medical and scientific literature shall be considered as meeting the requirements of reliable evidence.”

In reviewing the scientific literature on comprehensive ABA-based programs, the committee has determined that ABA does meet this definition of reliable evidence. Based on the commissioned meta-analysis, at least 37 controlled trials of comprehensive ABA programs have been published (removing overlap of studies included across multiple meta-analyses), which included four RCTs. While there are some issues with these studies as described above, they included well-defined clinical endpoints of cognitive ability or adaptive behavior skills that were measured using psychometrically validated and standardized measures that are commonly used within published autism research. These findings were further substantiated by the Song, Reilly, and Reichow (2024) umbrella review of NDBI comprehensive programs.

The TRICARE definition of reliable evidence is aligned with the broader evidence-based framework described above in that controlled trials and

meta-analyses often are situated at the top of that framework or pyramid. Using both the TRICARE definition of reliable evidence and the broader evidence-based practice framework that is used by international organizations to determine evidence, comprehensive ABA-based interventions are evidence-based practices. Finally, multiple medical, psychological, and other professional organizations endorse ABA-based interventions as evidence-based practices for autism, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Psychological Association (Green, 2025), and ABA-based interventions for autism are standard services covered by most insurance plans (see Chapter 4 for more detail on industry standards). For these reasons, the committee concludes that ABA-based interventions do meet TRICARE’s hierarchy of reliable evidence standard for proven medical care.

Related Research Issues

In addition to the general question of efficacy, it is important to address a variety of other topics within DHA’s approach to coverage of ABA interventions. These topics relate to the concept of and evidence for dosage, parent participation in ABA service delivery, and the understanding of ABA services and their effects in the context of implementation science.

Dose Response

In its reports to Congress, the Department of Defense (DoD) has frequently raised the question about the lack of evidence for defining an ABA dose-response appropriate to produce positive outcomes for individuals with autism: “While DHA continues to monitor the literature, there have been no significant advances in the ABA research with regards to defining dose-response (including intensity, frequency, or duration), for whom ABA is most effective, and what clinical outcomes could be expected as a result of ABA interventions” (DoD, 2024b, p. 7). It is the committee’s opinion that DHA is incorrectly applying a general pharmacological concept of dosage designed to cure a disease (such as the cubic centimeter quantity of amoxicillin prescribed for bacterial pneumonia) to ABA services that are instead designed to improve behavioral, adaptive, and/or developmental goals of autistic individuals.

There has been a variety of descriptive and nonexperimental group studies (Casarini, Du, & Galanti, 2024), very large group regression studies (e.g., n > 1400) (Linstead et al., 2017; Virués-Ortega, Rodriguez, & Yu, 2013), RCT studies (Eldevik et al., 2019), and meta-analyses (Eckes et al., 2023; Eldevik et al., 2009) that have addressed ABA intensity and duration. The general finding has been that greater intensity and duration of ABA produce significantly stronger positive outcomes for participants

than services as usual (i.e., eclectic programs; Granpeesheh et al., 2009; Linstead et al., 2016), although lower-intensity programs can also produce positive outcomes (Eldevik et al., 2006, 2012). Most research operationalizes high intensity as 15 to 20 hours of services, while lower intensity was 10 to 12 hours per week. The effects of ABA services offered for less than 10 hours a week are understudied in the literature. Lastly, at least one recent meta-analysis (Sandbank et al., 2024) found no association between ABA intensity and participant outcome, but the methodological procedures followed in that meta-analysis have been strongly criticized (Frazier, Chetcuti, & Uljarevic, 2025). Current best practice is to tailor the specific ABA intensity and services to the individual goals of the autistic recipient (Roane, Fisher, & Carr, 2016). The research field, however, continues to examine approaches for better defining ABA intensity for specific needs, including novel ways to use artificial intelligence and machine learning to accomplish this process (Cox, 2025).

Given the evidence to date, the committee finds that an intensity level of 10 to 20 hours a week of ABA service may produce positive outcomes for many autistic individuals. For those with profound autism and/or high support needs, the level of intensity may need to be greater, such as 30–40 hours per week. However, the intensity of services is to be based on the needs of the individual with autism (Ma & Travers, 2022; Reichle et al., 2021), priorities of families, and expertise of the professionals providing ABA services. The committee does not endorse a blanket recommendation that all individuals with autism should receive a uniform intensity (such as 30 or 40 hours per week of ABA services). To re-iterate, the decision about the number of hours per week of direct ABA services necessary to support changes in health outcomes should be developed by a professional behavior analyst based on (a) the number and type of goals being addressed in the intervention, (b) consideration of other services being provided to the client, (c) the client’s learning rate, and (d) family and client input.

Parent Involvement

The committee commends the focus on family-centered care in the updated ACD policies. Co-development of treatment strategies, goals, and processes is important for family engagement and improves outcomes (Dempsey & Keen, 2008). However, the ACD currently mandates parent training in ABA interventions as a condition for receiving ABA services for their children (see Chapter 4). Although parent involvement in their children’s ABA programs is key, the form of parent involvement may well be moderated by families’ capacity to engage. There is evidence that parent-implemented interventions result in positive outcomes for their autistic children (Cheng et al., 2023; also see the umbrella analysis previously

described). Here too, however, effects vary depending on the nature of the intervention and the capacity of families for implementing interventions (e.g., number of other children in home, single parent at home when spouse is deployed), and the stress experienced by parents may be alleviated or exacerbated (Rovane, Hock, & January, 2020). This may call into question the uniform parent training requirement imposed by ACD as a condition for receiving ABA services and the need for a more moderated, ecologically sensitive approach to making decisions about the level of parent involvement (Stahmer et al., 2015). See Chapter 4 for more discussion of the ACD’s parent training requirements.

Viewing ABA Intervention and Services from an Implementation Science Perspective

The implementation of empirically supported interventions such as ABA by service providers and received by autistic individuals and their families is a function of multiple factors (Lyon et al., 2017). The field of implementation science has emerged in the last two decades to study the influence of contextual factors that affect the delivery of evidence-based practices (Eccles & Mittman, 2006). Whether implementation of ABA interventions is successful depends on support at multiple levels, including payors, agency leaders, ABA providers, and individual clients (Boyd et al., 2022; Odom et al., 2021).

Implementation science researchers have created many models to determine the factors affecting implementation (Nilsen, 2015). A common feature of these models is that they primarily take an organization systems perspective (Odom et al., 2021), in which there are factors or influences close to the delivery of the intervention (i.e., inner context or setting) and those more distant from the intervention (i.e., outer context or setting) that are facilitators or barriers to implementation. Figure 5-5 depicts this relationship for one such model (Northridge & Metcalf, 2016). Examples of outer setting factors are the relocation of families every two years, TRICARE polices related to autism identification and service provision, and regional availability of ABA services. Examples of inner setting factors are the interpretation of TRICARE policies by various officials or administrators, reporting requirements for families and service providers in order to qualify for ABA services, and the local regulations affecting the speed of re-establishing ABA services after relocation.

Additionally, for autism services to be implemented well, “providers need a minimum level of knowledge about autism, leaders need to allow time for [supervision], parents or autistic individuals need to value participation in the intervention, and funders must be willing to pay for the infrastructure needed to support intervention implementation” (Boyd et al.,

SOURCE: Northridge & Metcalf, 2016.

2022, p. 570; e.g., Brookman-Frazee et al., 2025; Hieneman & Dunlap, 2000). Recent research has linked these factors with both provider and child outcomes (Augustsson et al., 2015; Ehrhart & Raver, 2014; Green et al., 2014).

Importantly, from an implementation science perspective, there is substantial evidence for the potential for ABA services, when properly implemented, to have important positive health and mental health outcomes for autistic individuals. Such potential is moderated by quality implementation of ABA services and the barriers and facilitators to such implementation. In the course of this committee’s deliberations, several barriers to implementation have been identified and discussed in other chapters of this report (see Chapters 3 and 4).

CONCLUSION

ABA is a set of intervention practices based on behavior analysis principles. ABA consists of focused intervention practices that service providers use to address individual therapeutic goals of autistic individuals and also comprehensive programs that use a variety of practices to address such goals. It is a common misperception that ABA is a single intervention.

This misperception is apparent in DHA’s reports to Congress, in which ABA is often characterized as one practice. In actuality, a broad range of evidence-based ABA interventions are available to address the complex health outcomes (e.g., communication, behavior, adaptive skills) of autistic individuals and their families. Like all interventions used to support individuals with autism, ABA services are highly individualized to the specific needs of every unique individual.

DoD reports to Congress have consistently indicated there is not sufficient evidence of the efficacy or effectiveness of ABA intervention for autistic individuals. The committee’s conclusion, as presented in this chapter, is that there is a substantial body of literature, supported by multiple meta-analyses, indicating strong evidence of efficacy and effectiveness, and that this evidence around ABA services does meet DoD’s criterion of reliable evidence of efficacy. The implications of these findings from the committee’s review of the scientific literature on ABA are discussed further in Chapter 7.

The current DHA conceptualization of dose response for ABA services reflects a misunderstanding of ABA services and practice. As this chapter describes, this concept conveys a perspective that ABA is a singular intervention that is delivered in units, with the expectation that there would be a similar response to dose effective across autistic individuals. This conceptualization does not recognize the vast heterogeneity within the autism population as well as the heterogeneity of ABA intervention practices that can respond to individual therapeutic goals, which can vary greatly from person to person and may not be linear in the traditional sense of dose-response. It is therefore not appropriate to quantify an appropriate amount of ABA services that is applicable to all (or even most) autistic individuals. Rather, ABA intensity and modality should be determined based on client needs and goals.

Similarly, while caregiver involvement in ABA programs can be beneficial for autistic individuals, its requirement as a condition for receiving ABA services through the ACD can be problematic, as noted in Chapter 4. Parents and families vary in their capacity for implementation and/or support of or involvement in ABA therapeutic practice. For some families with limited resources, such enforced involvement could be iatrogenic in that it could lead to greater family stress rather than less.

Conclusion: The effects related to the amount of applied behavior analysis (ABA) received (hours per week) as well as caregiver engagement in ABA are moderated by personal needs and families’ capacity to engage. Current standards of care direct individualized amounts of ABA and caregiver involvement.

This page intentionally left blank.