Artificial Intelligence to Assist Mathematical Reasoning: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 2 Overview and Grand Vision

2

Overview and Grand Vision

Moshe Vardi, Rice University, and Geordie Williamson, University of Sydney, presented an overview of and vision for using artificial intelligence (AI) to assist mathematical reasoning and participated in a joint discussion session moderated by workshop planning committee member Brendan Hassett, Brown University.

THE QUEST FOR AUTOMATED REASONING

Vardi provided a brief history of mathematical proof and reasoning, beginning in ancient Greece and leading up to automated reasoning in the present day. He described the ancient Greek concept of the deductive proof as an airtight argument whose concept marked the beginning of mathematical reasoning. Aristotle’s concept of the syllogism, reasoning that comes out of form, followed closely behind. The ancient Greeks also introduced the concept of the paradox, in which self-reference is a key feature.

Jumping to the 17th century, Vardi explained Gottfried Leibniz’s dream of a universal mathematical language—a lingua characteristica universalis—that could express all human knowledge, allowing calculational rules to be carried out by machines. In 1847, George Boole took a step toward this mathematical language with the creation of Boolean logic. This logic allows one to treat Aristotelean syllogisms algebraically, in that a logical “AND” can be viewed as a product, or an “OR” as a sum, for example.

Vardi noted that mathematical advances in the 19th century, particularly Georg Cantor’s proof that there exist infinitely many distinct infinities, caused mathematicians to consider more carefully what a rigorous proof is. In pondering this question, Gottlob Frege developed logicism, the idea of logic being foundational for mathematics. Logic as a language for mathematics allows one to, for instance, formalize Aristotelian syllogisms. However, in 1902, Bertrand Russell pointed out a paradox in Frege’s logical framework, sparking a foundational crisis in mathematics dubbed the Grundlagenkrise.

David Hilbert developed Hilbertian formalism in the 1920s in response to this crisis, Vardi continued, which requires mathematics to be consistent, complete, and decidable. Hilbert emphasized that proofs must be studied and treated as mathematical objects. Kurt Gödel’s incompleteness theorem proved shortly after shows that in number theory, the system cannot prove its own consistency, demonstrating that Hilbert’s program was impossible. To finish his historical account, Vardi presented Stephen Cook and Robert Reckhow’s 1979 definition that a proof system is an algorithm, and a rigorous proof is one that can be checked.

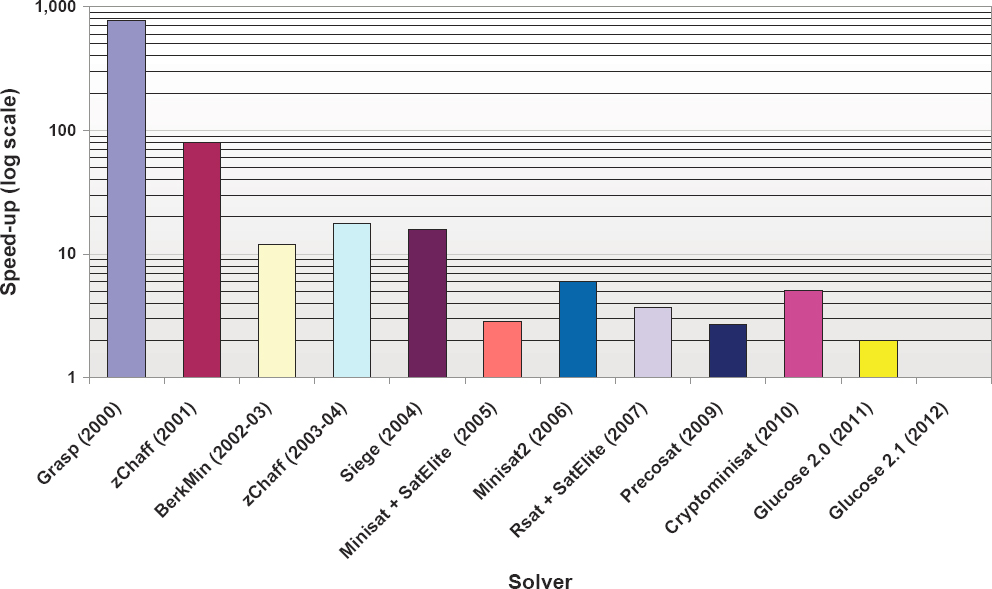

Vardi then turned to the Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT), a problem for which researchers have tried to automate solving. During the so-called SAT revolution in the mid-1990s, key tools were developed—including GRASP in 1996 and Chaff in 2001—and many modern SAT solvers use an algorithm called conflict-driven clause learning. Computers can now solve SAT problems with millions of variables (see Figure 2-1).

As another example, Vardi presented the Pythagorean triple problem, which asks whether the positive integers can be colored red and blue so that no Pythagorean triples (sets of numbers x, y, and z that satisfy x2 + y2 = z2) consist of all red or all blue members. By reducing the problem to SAT, Heule, Kullmann, and Marek proved the impossibility of this coloring (Heule et al. 2016). Their proof was developed and checked algorithmically.

In closing, Vardi remarked that the quest for automated reasoning is at the heart of mathematics and computer science. Huge progress has been made in Boolean reasoning, automated deduction, and proof assistants, as well as in the formal verification of programs and in formalized mathematics. He concluded his presentation with an open question about the future roles of deep learning (DL) and large language models (LLMs) for automated reasoning.

WHAT CAN THE MATHEMATICIAN EXPECT FROM DEEP LEARNING?

Williamson focused on how one can use DL to guide mathematical proof or reasoning at a high level. Citing Turing’s 1948 work Intelligent

SOURCES: Created by Sanjit A. Seshia, presented to the workshop by Moshe Vardi, Rice University, June 12, 2023.

Machinery, one of the first papers to suggest the possibility of AI, he noted that mathematics has served as a litmus test for AI from its very beginnings. The centrality of reasoning, which modern AI still struggles with, to the mathematical process makes mathematics an especially interesting and important area to test the power of AI. Williamson also remarked that AI may change the fields of mathematics and computer science dramatically. Keeping this in mind, he noted that mathematicians and computer scientists play a vital role in the conversation on steering the future of AI deliberately and carefully; he pointed to discussions in the 2022 Fields Medal Symposium that delve further into this topic.1 He emphasized that mathematical understanding is guided by a wide variety of sources, including intuition (e.g., geometric or physical), proof (whether informal or formal), notation, analogy, computation, and heuristics.

To give a “crash course in DL,” Williamson explained that one may think of a neural network (NN) as a type of function approximator. For example, one can imagine that a function could take as input the pixel

___________________

1 For more information on the 2022 Fields Medal Symposium, see http://www.fields.utoronto.ca/activities/22-23/fieldsmedalsym, accessed June 20, 2023.

values of an image of a tiger and output the probability that the image is of a tiger; as another example, a function could take as input an incomplete sentence and output a probability distribution on the next word. To create this function approximation with a NN, one can combine linear algebra with nonlinearities, applying gradient descent to move from an enormous space of possible functions toward a target function. Williamson presented an example using TensorFlow Playground2 that trained a function to classify orange versus blue nodes on a spiral. He emphasized that the process is stochastic, as well as not necessarily monotonically improving. Additionally, in general, he said that DL works best when (1) the input dimension is high, (2) the function is on the unit cube, and (3) coordinates have low symbolic content.

Providing advice on DL to the interested mathematician, Williamson expressed that NNs are difficult to interpret, which is especially important to note as understanding is vital to the mathematician. One should also expect engineering subtleties; the choice of architecture is important, and it can be unclear whether the implementation or the idea is at fault when encountering issues. Additionally, one should beware the “hype machine” that can produce misconceptions on the power of DL. Finally, he suggested that mathematicians work with DL experts—interdisciplinary work is challenging but worthwhile.

Williamson then presented an example of a problem in representation theory. A pair of permutations x, y can be associated with two objects, a Bruhat graph and a Kazhdan-Lusztig polynomial. Using DL, Williamson and his team approached the unsolved combinatorial invariance conjecture stating that there exists a relationship between these two objects. They trained a graph NN to predict the coefficients of Kazhdan-Lusztig polynomials, and it achieved high accuracy after just a few days of training. The difficulty was distilling understanding out of the model.

In studying the model’s behavior, the team noticed a hidden labeling of certain edges of the Bruhat graphs. Looking at edges deemed important by the model led to the discovery of hypercube-like structures within the graphs; with further work, the team eventually devised a formula proving a special case of the combinatorial invariance conjecture, opening the door to new work in combinatorics. Williamson concluded his presentation by citing two works that delve further into the topics he discussed (see Davies et al. 2021; Williamson 2023).

___________________

2 The TensorFlow Playground website is https://playground.tensorflow.org, accessed June 20, 2023.

DISCUSSION

Hassett moderated a discussion among the session’s speakers. He asked for the speakers’ thoughts on the role of mathematical intuition and DL’s relationship to it. Williamson remarked that for mathematicians, understanding comes from several axes, and he indicated that DL can provide another axis to enhance intuition. Vardi expressed appreciation for Williamson’s constructive approach, noting the fearmongering that often occurs around AI, and seconded Williamson’s thoughts on DL as another tool for mathematicians. Hassett then asked what machine learning (ML) may do for mathematicians’ understanding of theorems. With the caveat that the future is unpredictable, Vardi stated that these tools may provide support in areas where mathematicians lack intuition, and studying the large computational proofs that ML produces can lead to new insights. Currently, in many cases, NNs can solve a problem, but it is a mystery how: the algorithms are black boxes. Williamson noted that researchers generally have held the position that NNs will remain black boxes, but recent work has pointed toward the future possibility of distilling human comprehension from them.

Hassett inquired about the kinds of mathematical problems that will be susceptible to NN techniques. Because few data points exist, Williamson cautioned against being restricted by notions of what might or might not work. That said, these techniques seem to work better on problems with greater noise stability, but both Williamson and Vardi emphasized that they have consistently been surprised by the abilities of AI.

Noting that Williamson and Vardi have both conducted interdisciplinary research, Hassett posed a question about the language gaps that exist between mathematicians and ML researchers and how these gaps can be bridged. Vardi highlighted that between communities, even basic vocabulary is not necessarily shared, and one must always question assumptions and be flexible in thinking. Williamson added that interdisciplinary work takes time. It took a year, he approximated, to find a common language with his DeepMind research collaborators. Additionally, different research communities can have very different goals. Vardi suggested being open to changing how one views the world in order to truly work with another person.

Next, Hassett wondered whether the development of DL techniques changes the types of questions that researchers ask and choose to explore. Vardi answered that he does not see that change happening yet. At the moment, these tools are still being built. However, he continued, if these techniques become working tools for mathematicians, they will certainly influence how researchers think about mathematics. The belief in one’s ability to solve a problem is a key aspect of selecting a problem to study;

changes in tools will change methods of attack and thus the problems researchers choose to pursue. Williamson agreed and added that DL itself is built on rich mathematical foundations, and the problems that arise from DL research will also influence mathematics.

Finally, Hassett asked Williamson and Vardi for their advice for a young person looking to enter this area of research. Vardi expressed that the PhD path is best for a person who finds it intellectually thrilling to be at the interface between the known and unknown. Williamson emphasized that people should really take time to understand and follow the things they find interesting.

REFERENCES

Davies, A., P. Veličković, L. Buesing, S. Blackwell, D. Zheng, N. Tomašev, R. Tanburn, et al. 2021. “Advancing Mathematics by Guiding Human Intuition with AI.” Nature 600:70–74. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04086-x.

Heule, M.J.H., O. Kullmann, and V.W. Marek. 2016. “Solving and Verifying the Boolean Pythagorean Triples Problem via Cube-and-Conquer.” Pp. 228–245 in International Conference on Theory and Applications of Satisfiability Testing. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Turing, A. 1948. Intelligent Machinery. Teddington, Middlesex: National Physical Laboratory, Mathematics Division.

Williamson, G. 2023. “Is Deep Learning a Useful Tool for the Pure Mathematician?” arXiv preprint. arXiv:2304.12602.