Artificial Intelligence to Assist Mathematical Reasoning: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 5 Technical Advances Required to Expand Artificial Intelligence for Mathematical Reasoning

5

Technical Advances Required to Expand Artificial Intelligence for Mathematical Reasoning

On the final day of the workshop, speakers from computer science and mathematical backgrounds discussed technical research advances needed to expand the use of artificial intelligence (AI) for mathematical reasoning.

RESEARCH ADVANCES IN COMPUTER SCIENCE

The session on research advances in computer science highlighted speakers Brigitte Pientka, McGill University; Aleksandar Nanevski, IMDEA Software Institute; and Avraham Shinnar, IBM Research. Talia Ringer, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, moderated the discussion.

Principles of Programming and Proof Language

Giving an overview of the field of principles of programming languages, Pientka discussed what AI can do for mathematical reasoning from the perspective of the field’s community. She described the research landscape in this field as a combination of work in programming languages based on logical principles, proofs about programs and programming languages themselves—traditionally done on paper but increasingly using proof assistants, and implementation and evaluation of programming and proof environments. The idea that proofs can be thought of as programs is foundational to the field.

Pientka asserted that trust and reliability of programs is a central motivation for this research and becomes increasingly important as large language models (LLMs) can now generate code. Compilers, used to make code runnable by translating it into low-level machine instructions, are a key piece of software infrastructure whose bugs are notoriously difficult to find and fix. In the 1970s, a grand challenge posed by Tony Hoare asked the community to verify a compiler. The challenge was finally met in 2009 with CompCert,1 a fully verified compiler for C, using the Coq proof assistant. She emphasized this success as a testament to the value and power of proof assistants.

The language in which software is implemented is also crucial to reliability, Pientka continued. The language itself can be flawed, which makes it important to study the language designs themselves. Java exemplifies this well. It was one of the first languages with a formal, rigorous mathematical definition, and it claimed to be type-safe, meaning that a well-typed program will execute without issue. However, she explained that over the decades since its creation, researchers have investigated and debated that claim (see Amin and Tate 2016; Drossopoulou and Eisenbach 1997; Rompf and Amin 2016; Saraswat 1997).

Highlighting the differences between proofs in programming language theory and in mathematics, Pientka remarked that computer scientists are often proving the same kinds of theorems—such as type safety, bisimulation, soundness of a transformation, or consistency—for different languages. The difficulty lies in that the language itself is a moving target and can be quite large. She illustrated these differences with a metaphor of buildings: mathematics is like a skyscraper, and proof builds on earlier floors, stacking up to high levels. In programming languages, the ground is like an earthquake zone, and work goes into establishing the stability of smaller houses, ensuring they do not collapse.

Pientka explained that programming language proofs are difficult to write on paper because of the level of detail one must consider. Proof assistants can help but come with their own challenges. To use proof assistants, extensive work needs to go into building basic infrastructure; there are many boilerplate proofs; it is easy to get lost in technical, low-level details; and it is time-consuming and highly dependent on experience. For example, she presented an article that developed a theory using Coq and noted that out of 550 lemmas, approximately 400 were “tedious ‘infrastructure’ lemmas” (Rossberg et al. 2014), which is a common experience.

Returning to the idea of proofs as programs, Pientka noted the synergy between a few concepts in programming and proofs, including code and proof generation; code and proof macros; program and proof synthesis;

___________________

1 The CompCert website is https://compcert.org, accessed July 10, 2023.

and incomplete programs and incomplete proofs. Abstractions are also crucial to both programming and proofs. Consequentially, the two domains grow together, with advances in one domain applying to the other.

Pointing toward potential areas of future work, Pientka commented on the usefulness of collections of challenge problems. She noted the influence of POPLMark, which helped popularize proof assistants in the programming language community and served as a point of comparison across different proof assistants, tools, and libraries (Aydemir et al. 2005). There are also clear areas for improvement in interactive and automatic proof development, such as eliminating boilerplate proofs and gaining an overall better understanding of automation.

To conclude, Pientka summarized two main lessons. First, abstractions are key for the interplay between humans and proof assistants, and developing theoretical foundations that provide these abstractions is just as important as building new tools and engineering. Second, proof automation has high potential for programming language proofs. Because the goal of proofs is often clear and the language is a moving target, she underscored that one should, in principle, be able to port proof structures to new languages, making programming language theory a useful testbed for proof automation.

Structuring the Proofs of Concurrent Programs

Nanevski presented on presented on how and why to structure proofs, using the theory of concurrent programs as a running example. He explained that the idea of structuring is making proofs scale, which is connected closely to structured programming. Foundational to computer science, structured programming suggests that how programs are written matters (e.g., removing a command can improve clarity, quality, and development time). Structured proving/verification of programs is application specific, but he noted that a common thread exists between different applications. Reiterating Pientka’s earlier statement, he described this common thread as that programming and proving are essentially the same. For example, the Curry-Howard isomorphism formally establishes a connection between proofs and programs. The Curry-Howard isomorphism is foundational for type theory, which is the study of program structures and types as their specifications. Type theory, then, is foundational for proof assistants (e.g., Coq, Lean). However, he continued, although the Curry-Howard isomorphism is tied fundamentally to a state-free programming language (i.e., sufficient for writing proofs in mathematics, writing proofs about programming languages, and verifying state-free programs), a question remains about how to verify programs that fall outside of the state-free paradigm.

To begin to address this question, Nanevski explained how type theory can be applied more broadly to shared-memory concurrency programming models. The earliest proposal for a program logic on which a type theory for shared-memory concurrency could be built came from Owicki and Gries (1976). Nanevski detailed Owicki and Gries’s path to design a Hoare logic and their methods to verify the compositionality of a program, in particular, and observed two key ideas: (1) programs needed to be annotated with an additional variable state (i.e., the ghost state variable), and (2) resource invariants needed to be introduced. With these two added steps, verification became possible. He noted that by introducing a new state, new codes, and new programs for the sole purpose of designing a proof, Owicki and Gries blurred the distinction between programs and proofs.

Nanevski remarked that although this work was influential, several issues emerged. First, proofs depend on thread topology, but a two-thread subproof cannot be reused because it uses a different resource invariant—in other words, the program state leaks into the resource invariant, leading to false proof obligations, and one proves the same thing over and over again. This case demonstrates a failure of information hiding and in code/proof reuse. Second, without knowing a program’s number of threads, it is not possible to annotate that program. This reflects a failure of data abstraction.

Nanevski explained that a question also arises about how to disassociate proofs from the number and topology of threads, and he asserted that types are helpful in addressing this question. For example, one takes the judgment from the Owicki-Gries specification and turns it into a dependent type. He emphasized that in type theory, programs that differ only in the names of variables are the same program, but an additional abstraction is needed to make the types equal. He noted that this pattern of abstraction is so pervasive that a new type theory emerged as a default for the Hoare triple type. He said that each thread and Hoare type should have two local variables. These variables have different values in different threads, but the sum of the variables is the same in all threads, which means that the resource invariant has been disassociated from the number and the topology of threads. However, these local variables cannot be independent, and their relationship must be captured to generalize separation logic, which has been reformulated as a type theory. He added that proof reuse can be restored with parallel composition, and data abstraction can be restored by writing an incrementation program and hiding the thread topology with the types. He underscored that such approaches scale up for more sophisticated specifications and structures such as stacks, queues, and locks.

Nanevski concluded by summarizing a few keys to scaling mechanized verification. Proofs scale by improving their behavior in terms of

information hiding and reuse, especially proofs of programming correctness. Determining the right abstractions is essential but difficult. To find these abstractions, he suggested using type theory and generally experimenting with proofs; AI also may be helpful in this area. He noted that although correctness is the most commonly mentioned reason for proof mechanization, a second benefit is that, by facilitating such experimentation, it provides a way to gain insight to the structure of a problem. Finally, he reiterated the sentiment that advances in proofs are intimately tied to advances in programming, and the two will progress together.

Artificial Intelligence for Mathematics: Usability for Interactive Theorem Proving

Shinnar discussed current tools and automation for interactive theorem proving and ways to improve their usability. Machine learning (ML) can help, he imagined, in both the foreground and background of the proof assistant. In the foreground—that is, at the step in a proof where the user is currently working—ML tools could make immediate suggestions (such as suggestions of tactics or tactic arguments). In the background, slower but more powerful ML tools could work on the statements which the user previously marked with a placeholder proof (called an “admit” or “sorry” statement) and moved past. Such statements are typically numerous; researchers will often sketch out a high-level proof plan, temporarily assuming the truth of many statements that appear in this plan (rather than immediately working to prove them) so that their focus can remain on the plausibility of the plan as a whole. Another background task for ML tools could be suggesting improved names for lemmas.

Shinnar called attention to the importance of the user experience offered by ML tools. People writing formal proofs, like people who write other kinds of programs, typically do this work in an application called an integrated development environment (IDE), which is designed to help them do this work efficiently. For widely used programming languages such as Python, IDE tools offer a programmer ML support in a carefully designed way which does not interrupt workflow, including auto-complete tools like GitHub Copilot that quickly recompute “foreground” suggestions with each keystroke, as well as slower tools for “background” tasks that store suggestions unobtrusively for the user to consult later. For formal theorem proving languages, existing IDE tools for ML support do not yet offer this degree of user-friendliness. They have largely been written by academic ML researchers, and ML researchers’ incentives for publication are to maximize the number of tasks their ML tools can solve eventually, not to develop a good trade-off between success percentage and speed. Shinnar emphasized that formal proof developments are built

in composable, or modular, ways. For example, Coquelicot and Flocq are two libraries for Coq which themselves depend on the Coq standard library, and Shinnar’s library FormalML depends on both of these. Individual developers use FormalML and may contribute their code to that repository when it is finished. All of these pieces work together, but they are developed and maintained by different people. He advocated for ML models to be built modularly in the same way, with initial training on basic libraries and fine-tuning on higher-level libraries. One barrier to adopting this approach is that a system of composed models will not perform as well as a model whose whole training is done on the full library ecosystem for the test suite. The compiler community, for example, has accepted this trade-off because the composed system can scale to large programs and work for people who do not have access to supercomputers. Shinnar urged that the same should happen for ML models. However, he observed that this is also an institutional challenge, and that the community needs to be able to incentivize these systems, even if they do not perform as well, to achieve models that are usable, scalable, and work for everyone.

Discussion

Ringer moderated the discussion, and the speakers began by considering the importance of abstractions. Shinnar remarked that because proofs often look similar, it is faster to copy and tweak previous proofs than to identify the perfectly fitting abstraction. Using ML to abstract a lemma from the core parts of the proof would be useful for proving and could provide insight into the proof. Pientka added that it would be useful to have methods to abstract conceptual ideas beyond the level of tactics, such as what clauses and rules are used for certain kinds of proofs.

Ringer asked whether mathematicians truly need these kinds of logics and type theories, and, if so, how the speakers would convince them to invest in these foundations. Nanevski indicated that mechanization, for example, is a way to understand the structure of a problem and can lead to new mathematics. Pientka agreed, stating that formalizing theory in a proof assistant forces one to consider what underlies the theory. Furthermore, mathematical proofs can experience the same issue of “bugs” that computer programs do, and proof assistants lend certainty to the proofs. Shinnar noted that mathematicians also have the experience of writing the same proof over and over, naming integration as an area where “the standard argument” is often referenced.

Ringer posed another question about priorities when developing new type-theoretic foundations. Pientka stressed that the theory should be informed by practice. Metaprogramming, for example, is gaining traction

but does not have a clear foundation, so there is a need for new theory that can support proofs about properties of metaprograms. Nanevski added that theory should be informed not just by the kinds of programs being written but also by the support needed to build proofs. Shinnar cautioned that the core type theory and kernel should stay as small as possible, for trustworthiness, but should support layering of abstractions. Rather than making core logic expressive, he continued, researchers should build expressive logic and ensure the core system can support it.

A workshop participant’s question about research on proof environments directed toward machine use rather than human use prompted a discussion on the essential purpose of interactive proof assistants. Nanevski recited Edsger Dijkstra’s famous statement that humans should write for humans and have machines adapt, rather than vice versa, and Shinnar agreed that the fundamental need is for humans and computers to work together. Nanevski and Shinnar noted that the ability to build layers of abstraction simplifies a given problem, which is good for both the machine and the human. Along this line, Pientka observed that optimizing environments for either human or machine use is not necessarily exclusive.

Observing that some researchers frame proof assistants as a tool that is more difficult to use but provides greater certainty than working on paper, Ringer asked the speakers whether they had examples in which writing a proof was easier with proof assistants than on paper. Shinnar asserted that writing proofs in proof assistants can absolutely be easier than on paper. Programming language proofs often raise numerous cases, and the computer can enumerate what cases exist instead of one having to think deeply about what might arise. Additionally, a major part of theorem proving is discovering that some of one’s earlier definitions were wrong and returning to tweak them. On paper, it is unclear what part of the proof needs to be discarded and what can be reused; proof assistants take care of those details and provide much greater confidence. Shinnar and Nanevski both stated that they essentially only use proof assistants over paper because they allow for freedom to explore, although Pientka said she still writes many proofs on paper.

In response to a workshop participant’s question requesting recommendations for introductory books or papers for mathematicians to learn more about proof assistants, the speakers shared resources. Nanevski offered “Programs and Proofs,” a collection of lecture notes from a summer school led by Ilya Sergey.2 Pientka stated that something like POPLMark for mathematicians would be incredibly valuable, recalling her earlier remarks that it was a small enough challenge to provide an entry point

___________________

2 These notes can be found at https://ilyasergey.net/pnp, accessed July 2, 2023.

for exploration and even fun. Nanevski echoed her sentiment and urged the creation of learning ramps with simpler concepts to build up to the use of libraries like mathlib and offer an easier playground for exploration. Ringer summarized some other resources such as Jeremy Avigad and Patrick Massot’s book Mathematics in Lean3 and Kevin Buzzard’s blog, the Xena project4; Ringer also noted the existence of games for Lean and cubical type theory.

Concluding the discussion, Ringer asked a final question about which problems the speakers are most excited. Nanevski named compositional type theory or compositional cryptography, and Pientka named developing type theory for concurrent process calculi. Shinnar mentioned work that the ML community could do to help mathematicians with formalization.

RESEARCH ADVANCES IN THE MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES

Speakers Javier Gómez-Serrano, Brown University; Adam Topaz, University of Alberta; and Alex Kontorovich, Rutgers University, presented research advances in the mathematical sciences and participated in a discussion moderated by Brendan Hassett, Brown University.

Artificial Intelligence, Computer-Assisted Proofs, and Mathematics

Gómez-Serrano discussed recent advances in the interplay among AI, computer-assisted proofs, and mathematics. He asserted that although AI and mathematics have a relatively short history together, there is likely a long future with many opportunities for collaboration between the disciplines. He underscored that training mathematicians in ML will be vital.

Gómez-Serrano’s presentation centered on the three-dimensional (3D) incompressible Euler and Navier-Stokes equations from fluid dynamics. A famous open problem asks whether there exist smooth, finite initial energy data that lead to a singularity in finite time, called a blow-up solution. Gómez-Serrano recounted the history of the problem from the perspective of the numerical analysis and simulations community, explaining that for a long time, there was no consensus on whether the answer was yes or no. A breakthrough by Luo and Hou (2014) found an axisymmetric blow-up away from the axis. They considered a fluid inside a cylinder

___________________

3 The book can be accessed through the GitHub repository found at https://github.com/leanprover-community/mathematics_in_lean, accessed July 2, 2023.

4 The Xena project blog can be found at https://xenaproject.wordpress.com, accessed July 2, 2023.

spinning in one direction in the top half and in the other direction in the bottom half, which generates secondary currents. They showed numerically that these currents lead to a finite-time singularity on the boundary in the middle of the cylinder. Their results also suggested a self-similar blow-up—a solution that is similar to itself as one zooms in with an appropriate scaling (Luo and Hou 2014).

Gómez-Serrano’s team searched for this suggested self-similar solution using ML. Using a technique called physics-informed neural networks, developed by Raissi and colleagues (2019), Gómez-Serrano’s team found a self-similar solution numerically (Wang et al. 2023). He emphasized that the technique is fast and versatile, but even more significantly, it can discover new solutions that no one has been able to compute using traditional methods. He advocated for increasing the use of ML to complement traditional methods in mathematics.

Gómez-Serrano discussed his team’s strategy for future work, aiming to prove singularity formation for the 3D Euler and Navier-Stokes equations without boundary. In discussing his team, he noted that the project involves collaboration with an industry partner, which provides more access to more extensive computational resources. He concluded by expressing excitement toward future work, underlining that extensive recent progress has opened new avenues of research involving computer-assisted proofs and ML, and the interaction of both with mathematics.

Formal Mathematics and Artificial Intelligence

Topaz presented his experiences formalizing research-level mathematics and the ability of formal methods to act as a bridge between AI and mathematics. He distinguished library building from research mathematics, asserting that formal libraries capture a segment of mathematical knowledge in a formal system and are meant to be used in other formalization endeavors. They are large and include many contributors—for example, Lean’s mathlib includes over 1 million lines of code; has over 300 contributors; and covers a wide range of mathematics including algebra, topology, category theory, analysis, probability, geometry, combinatorics, dynamics, data structures, and logic. Conversely, projects for research mathematics work to formalize cutting-edge theory or results. They are more focused with fewer contributors and more direct collaboration, and they employ formal libraries—the Liquid Tensor Experiment is one such example. Despite these differences in library building and research mathematics, he noted that these two areas of formal mathematics share the features of being collaborative, asynchronous, and open.

Topaz illustrated the workflow of these collaborations, particularly noting the use of “sorry” placeholders for most intermediate statements’

proofs, which allows high-level proof structure to be planned more quickly, as previously described in Shinnar’s presentation. These sorry statements can be broken down into smaller components, and this process is done recursively until the target statements are tractable and can be handled directly. He highlighted how individual contributors can focus on individual targets that they feel most comfortable with, and the proof assistant ensures consistency, which enables smooth collaboration.

Topaz imagined ways in which AI, with its current capabilities, could help these projects. The first was an “AI collaborator” that would iterate through sorry statements and attempt to solve each one, which Shinnar also discussed. Topaz emphasized that the AI can be useful even if it is not particularly powerful. If it succeeds with a sorry statement, it helps; if it does not, the researchers will fill the sorry statement in later as they do in current workflows. A few transformer-based tools already exist, including GPT-f, HyperTree, and Sagredo. He urged researchers to optimize usefulness by focusing only on filling in proofs for now, since having AI frame definitions or theorem statements, for example, is quite challenging. A second way AI could assist is in user experience, specifically in searching for lemmas or integrating more functionality into the editor. Like Shinnar, Topaz noted that ML tools are most useful when they are integrated into the editor. He acknowledged a few barriers including cost, the need to maintain infrastructure, and the culture separation between open-source projects and for-profit industry organizations.

Topaz then discussed the synergies between mathematics and AI research. He noted that mathematics research can be split crudely into problem-solving and theory building. Formalizing mathematics involves attempting to understand the problem-solving process itself, and aspiring to find the right definitions and abstractions. He observed parallels in AI research where researchers are striving to augment the reasoning capabilities of LLMs with novel prompting techniques and often find challenges in having AI produce useful definitions. He concluded that between mathematics formalization and AI research, advances in one area can support the other, and he advocated for increased collaboration between the two.

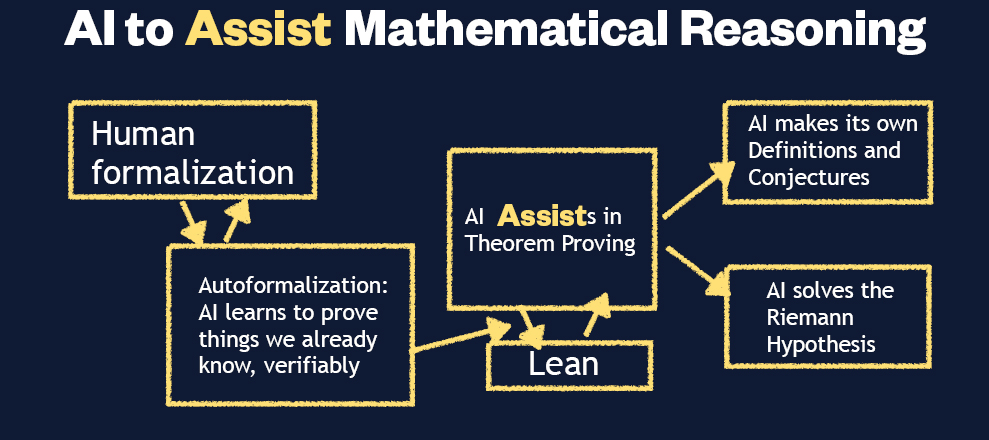

Artificial Intelligence to Assist Mathematical Reasoning

Kontorovich presented the path to developing AI to assist mathematical reasoning, offering several “conjectures” about the realities and future of the field. Working backward, he began with potential outcomes, imagining an instance in which AI solves the Riemann hypothesis. AI could provide a proof that is completely incomprehensible or perhaps give a perfectly comprehensible, beautiful proof. Furthermore, AI could

develop its own definitions and conjectures, supplying new mathematics by finding patterns in reasoning that are outside the current realm of mathematical thinking. Thinking more modestly, he predicted that AI likely will assist in mathematical reasoning. The current workflow of research mathematicians is to start with some idea; break it into smaller theorems, propositions, and lemmas; try computations using standard or non-standard techniques; and repeat. He observed that many steps within the process intuitively seem like they could be automated.

If AI is to assist the mathematical research process, Kontorovich continued, it will need to train on large datasets. He conjectured that LLMs trained solely on natural language will not be able to reliably reason mathematically at a professional level. He considered that almost all humans learn language automatically, but contributing to advanced mathematics requires years of training. Furthermore, unlike language, the underlying arguments of mathematics are solely deterministic. He noted that many researchers at Google and OpenAI are working to disprove his speculation, claiming that if AI had enough training data, parameters, transformers, etc., it would be able to solve professional-level mathematics problems. However, he posited the following question: Even if AI could solve professional-level mathematics problems just by training on language and give a result in natural language, how would one certify its correctness?

This question led Kontorovich to his second conjecture, stating that the path to AI assisting mathematical reasoning will be through an adversarial process, likely involving interactive theorem provers. He imagined a process involving feedback between an LLM and a theorem prover, with the LLM suggesting possible directions and the theorem prover certifying mathematical correctness of steps. Large datasets will be necessary to inform this feedback loop. At the moment, all formalized libraries combined do not have nearly enough data for this training. He also observed that open questions remain on the specifics of training, such as whether to train models on lines of code, pairs of goal states and next proof lines, or pairs of natural language lines and formal lines.

Kontorovich asserted that researchers will need to produce orders of magnitude more lines of formalized professional-level mathematics before AI can assist mathematics in this way. He offered a few reasons to be optimistic, noting that the pace of formalization has been increasing in recent years; proof assistants are able to support increasingly complex statements and proofs; and formalized proofs can sometimes be made to look exactly like human proofs. However, he underscored that a significant barrier to AI assisting mathematics remains: Humans alone will never be able to formalize enough mathematics to provide sufficient data for training. Autoformalization, in which AI formalizes problems with solutions already known to humans, is a promising area that could

help overcome this barrier. As a potential path forward, he suggested that mathematicians dedicate resources to improving human- and autoformalization (Figure 5-1), which may eventually lead to enough training data for AI systems to meaningfully and reliably assist mathematical research.

Discussion

Hassett moderated a discussion among the three speakers. He asked how a collaborative product like a large formal mathematics library interacts with traditional incentive structures in mathematics, given the difficulty of ascribing individual credit in such collaborative projects, and further inquired as to how the mathematical community can adapt. Topaz commented that this issue needs to be addressed in order for formalized mathematics to become mainstream. Kontorovich explained that reward mechanisms for the difficult, high-level, technical work of formalizing mathematics do not yet exist but should. He suggested that the interactive theorem proving community meet the mathematics community where it is. Formal mathematics libraries such as Lean’s mathlib, Coq’s Mathematical Components, Isabelle’s Archive of Formal Proofs and the Mizar Mathematical Library are each already a kind of journal, with maintainers who are effectively editors and a completely open, public trail. The theorem proving community could start a mathematics journal associated with formal mathematics library development, where significant contributions are associated with a paper that could, for example, include

SOURCE: Alex Kontorovich, presentation to the workshop.

meta-discussions about the work, ultimately allowing the work to be recognized by standard mathematical structures. He noted that mathematics formalization work is already included in computer science proceedings, but pure mathematicians do not have a broad awareness of the value in these proceedings. In addition to supporting Kontorovich’s suggestion, Gómez-Serrano urged the traditional mathematics community to build awareness of the publishing landscape in computer science.

Hassett asked another question about how LLMs might influence the speakers’ current work. Topaz recalled the demonstration he gave with sorry statements and described how AI could be useful; he added that as AI becomes a useful assistant, mathematicians will learn to write proofs in a way that is more amenable to AI assistance. Gómez-Serrano noted that one of the most significant contributions of LLMs is awareness—the attention on LLMs gives mathematicians an opportunity to educate the public.

Observing that breakthroughs in mathematics are sometimes driven by ideas cutting across different disciplines, Hassett wondered whether this process is uniquely human or if it could be supported by AI. Kontorovich replied that statistical models excel at finding patterns, and that ability could certainly provide a resource for connecting patterns across disciplines. Topaz and Gómez-Serrano agreed, and Gómez-Serrano highlighted how AI could have particular value in exploration.

Another question sparked discussion on how general methodology could be applied to numerous specific problems. Gómez-Serrano explained that the discovery phase in the work he presented was not tied to the particular problem he and his team were aiming to solve. The AI did not need much a priori knowledge about the physics to be surprisingly effective, but he stressed that work remains to understand why AI works this way. Hassett next asked about the extent to which AI can drive generalizations, which underlie the essence of mathematics. Topaz replied that one of the strong points of formalizing mathematics is that it forces one to find the right abstraction. Kontorovich added that pedagogically, since it is often easier to formalize general statements than specialized ones, formalization pushes one to understand the big picture. Topaz agreed, rearticulating that formalization drives extraction of ideas.

Hassett asked about the role of analogy as a driver for discovery and conjecture. Topaz emphasized that it is one of the main drivers of progress in mathematics. He speculated that analogy is related to the question of how AI can produce constructions and definitions, because in mathematics, definitions are often motivated by analogy. Inviting another perspective, the speakers consulted Ringer, who gave a brief explanation of how neural tools perform poorly at identifying analogies and about current architectural limitations for this ability that may be resolved in the future.

Hassett observed that some areas of mathematics, such as low-dimensional topology, are mainly driven by visualization and geometric insight, and he wondered how that could translate to formalization. Gómez-Serrano remarked that formalization in this area could resolve controversy about the correctness of proof by picture. Referencing proof widgets in Lean, Topaz asserted that the infrastructure for visualization while working on formalization does exist, which is promising for incorporating visualization into formalization. Kontorovich mentioned work on autoformalization that suggested AI could simply intake the visuals themselves from mathematical textbooks (see Szegedy 2020).

REFERENCES

Amin, N., and R. Tate. 2016. “Java and Scala’s Type Systems Are Unsound: The Existential Crisis of Null Pointers.” ACM SIGPLAN Notices 51(10):838–848.

Aydemir, B.E., A. Bohannon, M. Fairbairn, J.N. Foster, B.C. Pierce, P. Sewell, D. Vytiniotis, G. Washburn, S. Weirich, and S. Zdancewic. 2005. “Mechanized Metatheory for the Masses: The POPLMark Challenge.” Pp. 50–65 in Theorem Proving in Higher Order Logics: 18th International Conference, TPHOLs 2005, Oxford, UK, August 22–25, 2005. Proceedings 18. Berlin, Germany: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Drossopoulou, S., and S. Eisenbach. 1997. “Java Is Type Safe—Probably.” Pp. 389–418 in ECOOP’97—Object-Oriented Programming: 11th European Conference Jyväskylä, Finland, June 9–13, 1997. Proceedings 11. Berlin, Germany: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Luo, G., and T.Y. Hou. 2014. “Potentially Singular Solutions of the 3D Axisymmetric Euler Equations.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(36):12968–12973.

Owicki, S., and D. Gries. 1976. “An Axiomatic Proof Technique for Parallel Programs I.” Acta Informatica 6(4):319–340.

Raissi, M., P. Perdikaris, and G.E. Karniadakis. 2019. “Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Deep Learning Framework for Solving Forward and Inverse Problems Involving Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations.” Journal of Computational Physics 378:686–707.

Rompf, T., and N. Amin. 2016. “Type Soundness for Dependent Object Types (DOT).” Pp. 624–641 in Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGPLAN International Conference on Object-Oriented Programming, Systems, Languages, and Applications.

Rossberg, A., C. Russo, and D. Dreyer. 2014. “F-ing Modules.” Journal of Functional Programming 24(5):529–607.

Saraswat, V. 1997. “Java Is Not Type-Safe.” https://www.cis.upenn.edu/~bcpierce/courses/629/papers/Saraswat-javabug.html.

Szegedy, C. 2020. “A Promising Path Towards Autoformalization and General Artificial Intelligence.” Pp. 3–20 in Intelligent Computer Mathematics: 13th International Conference, CICM 2020, Bertinoro, Italy, July 26–31, 2020. Proceedings 13. Springer International Publishing.

Wang, Y., C-Y. Lai, J. Gómez-Serrano, and T. Buckmaster. 2023. “Asymptotic Self-Similar Blow-Up Profile for Three-Dimensional Axisymmetric Euler Equations Using Neural Networks.” Physical Review Letters 130(24):244002.