Artificial Intelligence to Assist Mathematical Reasoning: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 4 Current Challenges and Barriers

4

Current Challenges and Barriers

The workshop’s second session focused on challenges and barriers to the adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) for mathematical reasoning.

DATA FOR ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND MATHEMATICS: CHALLENGES AND NEW FRONTIERS

Sean Welleck, University of Washington, discussed the development of datasets specific to the mathematical sciences. He focused on the intersection of language models (LMs) and mathematics, noting a recent example of the large language model (LLM) Minerva’s success in producing a correct solution to a question from the Poland National Math Exam (Lewkowycz et al. 2022).

Welleck delineated a spectrum of formality for mathematical tasks, ranging from formal theorem proving to free-form conversation, which is more informal. He began explaining the usefulness of LMs by exploring their potential in the formal area surrounding proof assistants. He explained that LMs are often trained on massive amounts of general data, but small amounts of expert data can still be impactful. miniF2F is a common benchmark for evaluating LMs for formal theorem proving (Zheng et al. 2021).1 It consists of 488 problem statements, drawn mainly from

___________________

1 The GitHub repository for miniF2F can be found at https://github.com/facebookresearch/miniF2F, accessed June 29, 2023.

mathematics competitions, written in four different proof assistants. Relative to the size of general web data, this amount of problem statements is small, but he asserted that miniF2F has been an effective way to measure and drive progress in neural theorem proving.

Welleck next provided an overview of draft, sketch, and prove (DSP), a new method that employed miniF2F in its development (Jiang et al. 2022). It uses an LM to translate an informal proof into a sketch that guides a formal prover. From a data perspective, the project involved two components: (1) extending miniF2F’s set of formal problem statements to include the corresponding informal LaTeX statements and (2) writing 20 different examples demonstrating the translation from an informal proof to a sketch. One challenge of working with these expertly informed, small datasets is ensuring that problems from all kinds of domains are represented. ProofNet is another recent benchmark that draws from textbooks and aims to cover undergraduate level mathematics (Azerbayev et al. 2023). Welleck noted that these kinds of projects are valuable in broadening the scope of data, and he added that interdisciplinary collaboration is crucial for expanding this work.

Welleck stated that evaluating correctness for informal mathematical tasks is more difficult. This issue is vital for LMs, which generally do not guarantee correctness, as he demonstrated with an example of ChatGPT incorrectly answering and reasoning about an algebraic inequality problem. Expert evaluation, or having experts interact with these systems, can be useful in these cases. For example, Welleck presented NaturalProver, an LM that trained on theorems and partially completed proofs in order to generate a next step in a given proof (Welleck et al. 2022). He and his team asked experts to evaluate proof steps based on correctness and usefulness and to identify errors, resulting in a dataset of annotated proof steps. This project revealed that the models were sometimes capable of providing correct and useful next steps, and exposed the models’ areas of weakness in derivations and long proofs. Other groups are continuing this kind of work (see, e.g., Collins et al. 2023). Welleck described another way to build datasets by transforming problems that are difficult to evaluate into easier problems. For instance, LILA unified problem-solving datasets and transformed problems to be executable on a Python program (Mishra et al. 2022). He summarized that moving forward, it may be useful to continue exploring the interactions of LMs with humans and other computational tools, and to use these interactions and resulting feedback to expand the models’ coverage and reliability.

Finally, Welleck remarked that many LM-based tools either depend on closed data or are closed themselves. This can be a barrier to understanding data and ultimately to developing these models. Math-LM is an ongoing, open project with EleutherAI working to build a large corpus

model suite and evaluation harness for AI and mathematics.2 He stressed that open research and open data are vital to enabling new science and understanding.

Discussion

Kavitha Srinivas, IBM Research, moderated a discussion with Welleck. Srinivas began by clarifying that the success of the DSP method in training on small amounts of data partly hinged on leveraging the LM in combination with symbolic tools. She then asked about the issue of generalization, arising from both the scarcity and the particulars of the distribution of data for mathematical problems. Welleck responded that external tools could be helpful in augmenting LMs. For example, for proofs involving multiplication, a model may need to train on extensive amounts of data to learn how to multiply reliably, but multiplication could instead be offloaded to an external tool when applying the model. Referencing the LILA project, Srinivas wondered how incorporating external tools by having a system output a Python program compares to the Toolformer approach. Welleck specified that the LILA project focuses on the dataset, collecting data into a Python form, whereas Toolformer trains a model to automatically use different tools, like calling Python functions or a retrieval mechanism.

Srinivas and Welleck discussed the interaction between LMs and interactive theorem provers. Welleck expressed that LMs excel in translating between informal and formal expressions, whereas a traditional tool might have more difficulty generating natural language. Conversely, mapping expressions so that they are checkable by proof assistants offloads the verification portion of the task, for which LMs are not well equipped.

Given that proof strategies differ from one another in different areas, Srinivas asked if it is more effective for a dataset to be focused only in a particular area, like either algebra or calculus. Welleck expressed that both general and targeted datasets are useful. Datasets with high coverage can make it difficult to identify where a model is failing. Expanding on the issue of coverage, he specified that datasets in his current work aim to cover areas including elementary-level mathematical word problems, informal theorem proving, formal theorem proving, and math-related cogeneration tasks.

___________________

2 The GitHub repository for the Math-LM project can be found at https://github.com/EleutherAI/math-lm, accessed June 29, 2023.

BUILDING AN INTERDISCIPLINARY COMMUNITY

The session on building an interdisciplinary community highlighted speakers Jeremy Avigad, Carnegie Mellon University, and Alhussein Fawzi, Google DeepMind. Their presentations were followed by a discussion moderated by Heather Macbeth, Fordham University.

Machine Learning, Formal Methods, and Mathematics

Avigad outlined formal methods in mathematics and the benefits and challenges of collaboration between mathematics and computer science. Before introducing formal methods, Avigad distinguished between two fundamentally different approaches in AI: symbolic methods and neural methods. Symbolic methods are precise and exact, based on logic-based representations, and have explicit rules of inference; neural methods like machine learning (ML) are probabilistic and approximate, based on distributed representations, and require large quantities of data. He stressed that mathematicians need both approaches. Neural methods can reveal patterns and connections, while symbolic methods can help generate precise answers. Avigad then distinguished between mathematical and empirical knowledge as two fundamentally different types of knowledge. Like the distinction between symbolic and neural methods, mathematical knowledge is precise and exact, and empirical knowledge is imprecise and more probabilistic. The field of mathematics provides a precise way to discuss imprecise knowledge. For example, a mathematical model can be made using empirical data, and though the model may only be an approximation, it can be used to reason precisely about evidence and implications, and this reasoning can be useful for considering consequences of actions, deliberating, and planning.

Avigad described formal methods as symbolic AI methods, defining them as “a body of logic-based methods used in computer science to write specifications for hardware, software, protocols, and so on, and verify that artifacts meet their specifications.” Originating in computer science, these methods can be useful in mathematics as well—namely, for writing mathematical statements, definitions, and theorems, and then proving theorems and verifying the proofs’ correctness. Proof assistants, which are built on formal methods in mathematics, allow users to write mathematical proofs in such a way that they can be processed, verified, shared, and searched mechanically. He displayed an example of the Lean theorem prover, likening it to a word processor for mathematics. It can interactively identify mistakes as one makes them, and it also has access to a library of mathematical knowledge. This technology can be used to verify proofs, correct mistakes, gain insight, refactor proofs and libraries,

communicate, collaborate, and teach, among many other uses. Avigad referred workshop participants to several resources that delve further into how this technology can help mathematicians.3 He asserted that applying ML and neural methods to mathematics is a newer frontier, and recent work has used ML in conjunction with conventional interactive proof assistants. DSP, as discussed by Welleck, is one example that combines neural and symbolic methods (Jiang et al. 2022).

Turning to the topic of collaboration, Avigad remarked that digital technologies can bring together the two disparate fields of mathematics and computer science. In general, mathematicians enjoy solving hard problems, finding deep patterns and connections, and developing abstractions, whereas computer scientists enjoy implementing complex systems, finding optimizations, and making systems more reliable and robust. He underscored that these communities need one another. Digital technologies like proof assistants provide new platforms for researchers to cooperate and collaborate. The Liquid Tensor Experiment exemplifies this collaboration: formalization was kept in a shared online repository; participants followed an informal blueprint with links to the repository; participants communicated through the chat software Zulip; and a proof assistant ensured that pieces fit together, so each participant could work locally on individual subproblems. Another example of collaboration is the port of the large formal library mathlib, which required millions of lines of formal proof to be translated from the Lean 3 to Lean 4 system. Mario Carneiro wrote an automatic translator for some of this work, but user intervention was still necessary to repair some translations manually and sometimes rewrite lines entirely. Like the Liquid Tensor Experiment, the port of mathlib has online instructions to guide volunteers who stay in constant communication over Zulip, as well as dashboards to monitor progress.

Avigad enumerated a few institutional challenges to advancing AI technology for mathematical research. Neither industrial research that

___________________

3 Avigad’s resources include his preprint, J. Avigad, “Mathematics and the Formal Turn,” https://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/avigad/Papers/formal_turn.pdf, as well as presentations found at Isaac Newton Institute, 2017, “Big Conjectures,” video, https://www.newton.ac.uk/seminar/21474; Leanprover Community, 2020, “Sébastien Gouëzel: On a Mathematician’s Attempts to Formalize His Own Research in Proof Assistants,” video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sVRC1kuAR7Q; Institut des Hautes Études Scientifiques, 2022, “Patrick Massot: Why Explain Mathematics to Computers?,” video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1iqlhJ1-T3A; International Mathematical Union, 2022, “Kevin Buzzard: The Rise of Formalism in Mathematics,” video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SEID4XYFN7o; The Fields Institute, 2022, “Abstract Formalities,” video, http://www.fields.utoronto.ca/talks/Abstract-Formalities; University of California, Los Angeles, “Liquid Tensor Experiment,” video, http://www.ipam.ucla.edu/abstract/?tid=19428; and “Algorithm and Abstraction in Formal Mathematics,” video, https://www.ipam.ucla.edu/abstract/?tid=17900, all accessed August 2, 2023.

is driven by corporate interests nor academic research that is focused on specialization is perfectly aligned with developing such technologies. Academia in particular is governed by traditional methods of assessment. Both mathematicians and computer scientists invest significant time and energy into developing these technologies before they are recognized by traditional reward mechanisms. Avigad therefore advocated for new incentive structures for activities like ongoing development and maintenance of systems, libraries, or web pages and collaboration platforms.

Avigad concluded that advances in AI for mathematics will require input from distinct communities, including computer scientists working in formal methods, computer scientists working in ML, and mathematicians working to apply AI to mathematics. Progress will come from collaboration, and advances in technology both necessitate and provide new platforms for collaboration. He suggested that mechanisms to assess new kinds of mathematical contributions are required for advancement in the field, and better institutional support should be built for collaborative, cross-disciplinary work.

Challenges and Ingredients for Solving Mathematical Problems with Artificial Intelligence

Fawzi discussed using AI to solve mathematical problems from his perspective as an ML researcher. Recent breakthroughs in image classification, captioning, and generation; speech recognition; and game playing have all relied on ML. He highlighted the challenges of applying AI to mathematics specifically and suggested some best practices for collaboration to this end.

The first challenge Fawzi presented was the lack of training data in mathematics. ML models rely on large amounts of data, but data in mathematics are limited. There are few formalized theorems that a model could use for training compared to the vast number of images available for training an image classifier, for example. Synthetic data can be used instead, but this approach produces its own challenges. The distribution of synthetic data may be quite different from the target, and the model will not be able to generalize; however, he suggested that reinforcement learning could be useful in this situation. Another challenge arises owing to the different goals of ML research and mathematics research. For example, ML research generally focuses on average performance across many data points, while mathematics research is usually concerned with finding the correct result in one instance (e.g., proving one theorem). A third challenge Fawzi identified surrounds the tension between performance and interpretability. Mathematicians are interested in interpretable results and understanding how solutions are found, not just the solutions themselves. However, most

major ML breakthroughs have been driven by optimizing performance, and he noted that it is difficult to interpret the decisions made by ML models.

Fawzi enumerated several best practices for collaboration, beginning with an explanation of the difference between partnership and collaboration. A partnership between a mathematician and an ML researcher occurs when the mathematician formulates a problem, the ML researcher runs the experiment and returns the results, and the process repeats. Instead of such a partnership, he advocated for collaboration, in which an ML researcher and mathematician somewhat understand one another’s research and role, and they work together from the beginning. Collaboration is particularly important when using ML for mathematical problems because ML models require a degree of tailoring, and the ML researcher needs an understanding of the mathematical domain to refine the model. He stressed the value of breaking the communication barrier to facilitate effective collaboration. Time taken to understand the other party’s domain, especially at the beginning of a project, is time well spent.

The second best practice Fawzi identified was to establish metrics for progress early and to set up a leaderboard, which he deemed necessary for iterating over ML models. Metrics allow ML researchers to track and guide progress, and models cannot improve without this roadmap to define improvement. A leaderboard, especially one that connects directly to the experiments and updates automatically, encourages team members to test ideas and score them quickly, leading to more rapid improvement.

Fawzi’s final best practice was to build on existing works. He explained that researchers could build on top of theoretical frameworks, successful existing ML models, or traditional computational approaches. ML researchers tend to work from scratch, but he asserted that building on existing knowledge is a better practice. Setting a project in solid foundations by establishing good collaboration, choosing useful metrics, and identifying an existing base of work to begin from can lead to greater success.

Discussion

Macbeth led a discussion on collaboration between mathematics and computer science and how the domains may bolster one another. Noticing that both speakers’ presentations mentioned differences between mathematicians and computer scientists, Macbeth prompted them to discuss the cultural differences they perceived further. Avigad and Fawzi each affirmed the other’s depiction of the fields. Avigad reiterated that mathematicians tend to focus more on developing theory while computer

scientists are interested in efficiently solving practical problems, but he pointed out that the two approaches are not disjointed. There can be a deep respect for the different skills that each field offers. Fawzi agreed and highlighted the engineering work that is fundamental to ML.

Workshop participants posed several questions about benchmarks in each of the speakers’ work. Fawzi emphasized that metrics are crucial to the process of developing ML models, and benchmarks should be determined carefully at the beginning of a project. He cautioned that it is easy to choose ill-fitting benchmarks without prior knowledge of the domain; collaboration between ML and domain experts is therefore key to choosing useful benchmarks. Avigad explained that benchmarks are one area in which ML and mathematics differ; ML generally relies on benchmarks while in mathematical inquiry, the questions may not yet be clear or new questions may continually arise. Evaluating progress in the two domains can be quite different, which makes collaborating and combining approaches more useful than relying on only one or the other domain. He also described his work on ProofNet, which gathered problems from undergraduate mathematics textbooks to serve as benchmarks for automatic theorem proving (Azerbayev et al. 2023).

A few questions sparked discussion on how using AI for mathematics may benefit AI more broadly. Avigad speculated that in many cases, practical applications of AI could benefit from mathematical explanations and justification. For example, ChatGPT could explain how to design a bridge, but obtaining mathematical specifications and proof of safety before executing the design would be reassuring. Fawzi added that since interpretability is critical to mathematics, developments in ML for mathematics may advance work on interpretability of ML models overall.

THE ROLE OF INTUITION AND MATHEMATICAL PRACTICE

A session on the role of intuition and mathematical practice highlighted speakers Ursula Martin, University of Oxford, and Stanislas Dehaene, Collège de France. Petros Koumoutsakos, Harvard University, moderated the discussion that followed their presentations.

How Does Mathematics Happen, and What Are the Lessons for Artificial Intelligence and Mathematics?

Martin provided an overview of how social scientists understand the practice of mathematics. She defined the mathematical space as the theorems, conjectures, and accredited mathematical knowledge in addition to the infrastructure that supports the practice of mathematics, which

comprises the workforce (i.e., researchers, educators, students, and users), employers, publishers, and funding agencies. She observed that mathematical papers are published in essentially the same model that has been used since the 17th century, though the rate of publication has grown in the past few decades, especially in China and India.

To elucidate “where mathematics comes from,” Martin offered the example of Fermat’s Last Theorem, conjectured in 1637 and solved by Andrew Wiles and Richard Taylor in 1995. She relayed pieces of an interview with Andrew Wiles about his process developing the proof (Wiles 1997). She highlighted how the process, rather than containing singular moments of genius or sudden inspiration, required extensive trial and error. For months or years, researchers do all kinds of work, such as trying computations and studying literature, that is not included in the final paper. Martin stressed that breakthroughs that may happen near the end of this process rely on the long, arduous work beforehand, with the brain working in the background toward broad understanding of a problem. The advancement of mathematics also relies on researchers’ ability to understand and build on existing literature. Furthermore, she asserted that collaboration is crucial; it allows for the co-creation of ideas and the sharing of feedback, and it develops and reinforces the collective memory and culture of mathematics.

Martin described the Polymath Project, which demonstrated a new, collaborative way of developing mathematics instead of employing the traditional publication model. Started by Timothy Gowers in 2009, the Polymath Project invites people to collaborate online to solve a mathematical problem (Gowers 2009). Martin displayed some blog comments from the project to demonstrate how participants communicated: mathematicians engaged in brief exchanges and checked one another’s work or presented counterexamples. She emphasized that one crucial key to success was that leading mathematicians set communication guidelines for the project, such as a rule for being polite and constructive. The first problem ultimately solved by the collaboration—a proof for the density Hales-Jewett theorem—was published in mathematical papers under the pseudonym D.H.J. Polymath.

Martin identified some challenges that the Polymath Project brought forward surrounding (1) the role of the leader, (2) pace and visibility, (3) credit and attribution, and (4) makeup of participants. To support this type of collaboration, the leader has the demanding job of both following the mathematical conversation and guiding social interactions, including mediating disagreements. Pace and visibility are difficult to balance because the project should encourage new participants to join, even though doing so can be intimidating. Credit and attribution are a clear challenge against the traditional structure of mathematics research

that incentivizes individual activity. Finally, online collaboration has the potential to lead to increased accessibility for and diversity of participants, but it does not automatically do so.

Martin presented an analysis of one of the Polymath Project’s problems that identified the kinds of contributions participants made throughout the process (Pease and Martin 2012). Only 14 percent of contributions ended up being proof steps; the other 86 percent was comprised of conjecture, concepts, examples, and other contributions. She remarked that much current work on AI to assist mathematical reasoning studies using AI not just for proof but also for conjecture and discovery of concepts, reflecting Pease and Martin’s findings.

In closing, Martin speculated that AI may deliver an abundance of mathematics and urged the community to plan for this future. She summarized that traditional mathematical papers present and organize mathematical knowledge; are accredited by proof; are refereed and published; give notions of credit, attribution, and accountability; and are embedded in and guided by the mathematical ecosystem. All of these features are important, she continued, and should be preserved as mathematics evolves. She concluded that mathematics is not just about writing proofs; acknowledging that mathematics lives in a broader context shaped by human factors will better allow stakeholders to take initiative and collaborate to create new mathematical practices—for example, using AI to assist mathematical reasoning.

Can Neural Networks Mimic Human Mathematical Intuitions?: Challenges from Cognitive Neuroscience and Brain Imaging

Dehaene provided a psychological and neuroscientific perspective of mathematical understanding and AI. He discussed how well artificial neural networks (NNs) mimic human cognition and learning. Current NNs successfully model the early stages of vision (e.g., reading) and some aspects of language processing, but they do not perform nearly as well as the human brain at many tasks related to mathematical learning and reasoning. For example, the human brain is able to learn from a very small number of examples, and it is better in its achievement of explicit representations than NNs. He focused on how the human brain, unlike NNs, learns from a combination of approximate intuitions and precise language-like symbolic expressions.

Dehaene explained that even very young children possess the mathematical intuition that untrained artificial NNs lack. Infants in the first year of life react to violations of the laws of arithmetic and probability. The capacity for geometry is similarly ingrained, which he supported by showing examples of art from the Lascaux cave in the form of geometrical

drawings. Such numerical and geometrical symbols can be found in all human cultures.

Dehaene asserted that humans possess a unique ability to understand abstractions, presenting a study in which humans predicted the next item in a geometrical sequence (Amalric et al. 2017). Subjects in the study could make correct predictions based on very little information because of geometric intuition. This intuition is a kind of language of thought that recognizes geometric rotations and symmetries and can combine these understandings into a formula that gives the next item in the sequence. This language of mathematics allows one to compress spatial sequences in working memory, thereby recognizing complex sequences that have spatial regularity (Al Roumi et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2019).

Another example compared the abilities of humans and baboons to identify an outlier in a group of quadrilaterals (Sablé-Meyer et al. 2021). Humans varying in age, education, and culture could easily identify a parallelogram in a group of rectangles, for example, but struggled more with groups of irregular shapes. Baboons did not show this geometric regularity effect; they performed equally across various quadrilaterals, regardless of regularity (i.e., regularity in a group did not lead to improved performance as in humans). Dehaene speculated that the intuition of numbers and shapes has the same evolutionary foundations for humans and baboons, but in humans, this ability is tied to a language of thought or mental construction that non-humans do not possess. In the study, a convolutional NN could capture baboon behavior but generally not human behavior; a symbolic model fit human behavior much better. Sable-Meyer and colleagues believe that humans rely on both an intuitive processing of shapes, like other primates, as well as a unique symbolic model.

Dehaene turned to a discussion of current AI, presenting a few examples to demonstrate its lack of ability in processing geometrical shapes. He displayed a picture of several eggs in a refrigerator door and stated that an NN classified it as an image of ping pong balls. It is clear to humans that the eggs depicted are not ping pong balls because they do not have a spherical shape, but the AI was not attuned to the precise geometrical properties that make a sphere. Another example showed an image generator that was unable to create a picture of “a green triangle to the left of a blue circle,” instead offering images with a blue triangle within a green triangle or a green triangle within a blue circle, for example (Figure 4-1).

Discussion

Koumoutsakos moderated a discussion between Martin and Dehaene on mathematical intuition, especially spatial intuition, and its relationship to AI. Koumoutsakos shared a workshop participant’s question on

SOURCES: Stanislas Dehaene, Collège de France, presentation to the workshop. Generated with DALL-E 2 with thanks to Théo Desbordes.

the ability of AI not just to verify existing proofs but also to discover new mathematics. Martin and Dehaene both asserted that AI could certainly aid in discovery and conjecture, and indeed it already has. Martin highlighted that the current mathematical knowledge base is so large that it is easy to imagine new mathematics being generated from what already exists.

A few questions prompted Dehaene to delve further into the limits of current AI and mathematical reasoning. He explained that NNs are inherently limited by the way data are encoded. This approximate nature may

work for the meanings of words, but the limitations become apparent when one considers the meaning of a square, for example, which has a precise definition that is not captured by an approximation. He observed that other technology exists with the ability to make exact symbolic calculations far beyond human ability. The issue is that this technology is not currently connected to language models, barring a few experiments. The human brain bridges between language and mathematical reasoning, allowing one to go back and forth and use both complementarily; he suggested that perhaps a way to connect these different technologies would allow AI to mimic the brain adequately, mathematical reasoning included.

One workshop participant asked the speakers whether mathematical intuition could be programmed into AI. Martin observed that intuition is a “slippery” term, as one person’s intuition is not necessarily the same as another’s. She suspected that because the definition of intuition will continually evolve, it is difficult to determine whether mathematical intuition can be programmed into AI. Dehaene wondered whether it is necessary for AI to have mathematical intuition the way humans do. Human brains are limited to the architecture produced by evolution, but AI is free from that constraint and need not mimic the brain’s architecture. He suspected that the use of other kinds of architectures may allow AI to work differently and perhaps reach far beyond human ability, comparing this idea to the way an airplane flies quite differently from a bird. Koumoutsakos asked how researchers could discover such architectures, which would differ radically from human intelligence. Offering AlphaGo Zero as an example, Dehaene remarked that starting from very little and allowing the machine to make discoveries on its own may be promising.

Finally, a question about the power of AI prompted Martin to note that in addition to AI training on existing data, AI also trains society, in a sense. As output from AI grows, she continued, people learn to expect certain text in particular forms (e.g., people expect text in children’s books to be simpler than that in books for adults). She wondered how and to what extent the output from AI conditions people’s use of language.

CONCENTRATION OF MACHINE LEARNING CAPABILITIES AND OPEN-SOURCE OPTIONS

Stella Biderman, Booz Allen Hamilton and EleutherAI, presented in the next session on the concentration of ML capabilities within few institutions and the potential for open-source practice. She focused on large-scale generative AI technologies, explaining that her work is primarily on training very large, open-source language models such as GPT-Neo-2.7B, GPT-NeoX-20B, and BLOOM, as well as other kinds of

models like OpenFold, which is an open-source replication of DeepMind’s AlphaFold2 that predicts protein structures.

Biderman explored the centralization of ML capabilities, specifying that the models themselves as well as funding, political influence and power, and attention from media and researchers are all centralized. Breaking into LLM research is difficult for several reasons. First, training an LLM is expensive; computing costs alone for a model can range from $1 million to $10 million, and it can cost 10 times more for an organization to enter the field. Second, training a very large LLM requires specialized knowledge that most AI researchers do not have. Biderman estimated that most AI researchers have never trained a model that requires over four graphical processing units (GPUs), and these very large models require hundreds of GPUs. Finally, the GPUs themselves are difficult to obtain. A small number of companies control the supply of cutting-edge GPUs, and most groups cannot get access to them. For example, a waiting list has existed for the H100, NVIDIA’s most recent GPU, since before it was released. Each of these factors reinforces centralization of ML capabilities.

Biderman stated that centralization influences what researchers can access. A spectrum of levels of access to large-scale AI technologies exists ranging from open source to privately held. Open source is the most permissive (e.g., T5, GPT-NeoX-20B, Pythia, and Falcon), followed by limited use, which typically constrains commercial use (e.g., OPT, BLOOM, and LLaMA). Application programming interface (API)-only is more restrictive and often offers partial use of a model for a price (e.g., GPT-3, GPT-4, Bard, and Bing Assistant). Privately held is the most restrictive level (e.g., PaLM and Megatron-DeepSpeed NLG). Most powerful models are privately held or were originally privately held and later released as API-only. Biderman asserted that research conducted with privately held models creates a bottleneck for AI research for the larger scientific community, because research with these models does not have practical applications for most people due to lack of access to the models.

Even open-source models are highly concentrated within a few companies, Biderman recognized. Eight companies to date have trained models with over 13 billion parameters, seven of which are for-profit companies. Thus, the release of open-source LLMs as a way to democratize and increase access to these technologies is still influenced by the needs of a small number of organizations.

Biderman enumerated several reasons why the concentration of ML capabilities can be considered a significant issue. Ethics—a belief that scientific research and tools should be publicly released—and finances—the costs of tools built on commercial APIs—may both affect a researcher’s understanding of the problem. This concentration also creates limitations

in applications of LLMs; the small number of individuals creating and training these models may lack diversity and cause disparate impact based on their priorities. For example, almost all state-of-the-art language models that are trained on a specific language use English texts, and almost all others use Chinese texts. It is extremely difficult for someone who does not speak English or Chinese to access a usable model of this kind. In the field of AI for mathematical reasoning, plenty of exciting research is being done—for example, Baldur (First et al. 2023) and Minerva (Lewkowycz et al. 2022)—but Biderman said there is no reason to believe that these models will ever be accessible to mathematicians except the few researchers working on these projects.

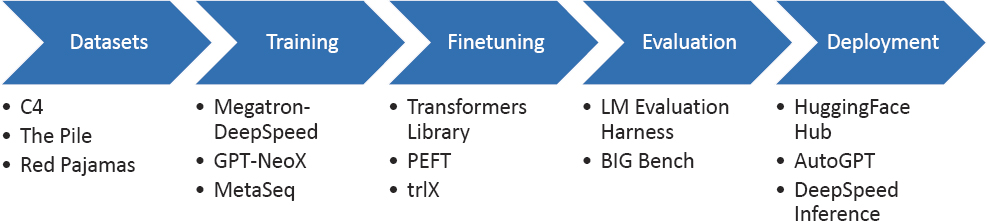

Recounting the story of OpenFold and DeepMind’s AlphaFold2, Biderman described how open-source work can influence the larger research landscape. As open-source capabilities approached the state of the art, DeepMind decided to license AlphaFold2 for non-commercial use months before OpenFold’s release. Biologists and chemists who could not previously access the model were finally able to use it for scientific research. In closing, Biderman asserted that a thriving open-source ecosystem for LLMs exists now and shared several resources for the different steps of developing LLMs (Figure 4-2).

Discussion

Terence Tao, University of California, Los Angeles, moderated the discussion session, beginning with a question about priorities for large open-source AI efforts. Biderman replied that building an interested community is essential for all open-source work, both at the beginning and throughout the project. Citing her work with EleutherAI, she described how hundreds of users participate daily, submitting code and discussing AI. The community’s assistance and support are critical for maintenance

SOURCE: Stella Biderman, presentation to the workshop.

and keeping up with the rapidly changing field; however, she noted that managing volunteers is a challenge in and of itself.

Tao asked what cultural changes are needed to encourage collaboration in the open-source community and how the projects can avoid being co-opted by other interests. Biderman stressed that a huge amount of collaboration already exists in the open-source AI community, sharing tools, advice, and research projects. The communication breakdown often occurs between those engaged in open-source research efforts and for-profit organizations that are less interested in open-source work. She invited a broader range of people to join open-source AI efforts, emphasizing that much of the infrastructure and work underpinning large-scale AI systems is standard software engineering and data science—one does not need to be an AI expert to contribute.

A workshop participant asked whether there are LLMs that have been trained on mathematical material and are widely available to mathematicians. Biderman responded that it is common to train LLMs on mathematical material; for example, standard LLMs use data from arXiv and PubMed. In particular, she named Goat,4 which is a fine-tuned version of a model called LLaMA that focuses on correct arithmetic computations. Another example is Meta’s Galactica,5 which trained exclusively on scientific corpora and was advertised as an assistant for writing scientific texts and answering scientific questions.

In a final question, Tao inquired about the role of the U.S. government in encouraging open-source AI research, and Biderman asserted that it would be most helpful for the government to create and release a dataset that the large-scale AI community could use for training. The community faces a “legally awkward situation” in which large organizations train LLMs on anything that can be downloaded from the Internet and are comfortable that they will not be punished because this is practiced so widely. For smaller organizations, especially those without many lawyers, the legal uncertainty provides a barrier to doing any work that involves transparency about data sourcing. No publicly available dataset exists that is large enough to train an LLM and is known to be fully license compliant. She added that another role for the government could be to supply additional GPUs, along with support for researchers on how to train on large numbers of GPUs.

___________________

4 The GitHub for the Goat website is https://github.com/liutiedong/goat, accessed July 24, 2023.

5 The Hugging Face page for Galactica is https://huggingface.co/facebook/galactica-1.3b, accessed July 24, 2023.

MATHEMATICAL FOUNDATIONS OF MACHINE LEARNING

Tao moderated the next session on the mathematical foundations of ML featuring Morgane Austern, Harvard University, and Rebecca Willett, University of Chicago.

Mathematical Foundations of Machine Learning: Uncertainty Quantification and Some Mysteries

Observing that ML algorithms are increasingly used for decision making in critical settings, such as self-driving cars and personalized medicine, and that errors can have severe consequences, Austern stated building trustworthy AI is essential. A first step in this direction can be made by reliably quantifying uncertainty. Uncertainty quantification (UQ) in ML is the process of quantifying uncertainty of an ML algorithm’s prediction. Closely related is the idea of calibration, in which ML researchers seek quantify how well the machine estimates the uncertainty of its own predictions.

Austern explored UQ and risk estimation in ML by focusing on classification problems, which are a type of supervised learning problem. In these problems, data are in pairs of observations and labels—for example, data may be pairs of images and the type of animal depicted—and the goal is to train an algorithm to label new observations. After training the algorithm, the first question one can ask regarding risk estimation is how well the model performs on unseen data (i.e., data it was not trained on). Risk can be measured by the probability that the algorithm will misclassify a new observation. She explained that a naïve way to estimate risk could be to study how many examples in the training data were misclassified; however, this systematically underestimates risk. Instead, one of the most common methods used to estimate risk in traditional ML is the K-fold cross-validation method, which splits data into some number of sections K. Each unique section is withheld, and the model is trained on data from all other sections and then tested on the withheld section. Risk is estimated by averaging the number of misclassified examples in all K iterations of the process. A data efficient way to perform this method is by using K equal to the number of observations (Austern and Zhou 2020).

Turning to NNs, Austern noted that modern deep learning (DL) algorithms can achieve extremely high accuracy, but since none can be perfect, calibration is important. She defined a well-calibrated model as one that faithfully reflects its own uncertainty. NN models produce confidence scores as part of their training, but they are notoriously poorly calibrated and overconfident, necessitating more reliable, external quantification of their uncertainty. One technique is to use prediction sets: a model can

return a set of potential labels for an observation, rather than just one, with very high confidence that the correct label is in the set. This can be done even for poorly calibrated or black box algorithms through a method called conformal inference.

Calibration is also an important issue for LLMs, Austern stated, that garners special interest because of their infamous tendency to “hallucinate.” Because many of these models are black boxes, confidence is measured through repetitive prompting, which is a kind of sampling. She noted that work in this area is still experimental.

Austern next discussed theoretical understanding of deep NNs. She posited that perhaps mathematical formulas or theorems could be used for UQ, though the theoretical behavior of deep NNs is not well understood. She focused on one “mystery” in particular: generalization. Classical learning theory favors simpler solutions; if a model is too complicated, it tends to overfit the data and perform worse at prediction. DL models, however, follow a different pattern. As model complexity increases, error decreases until a certain threshold in which performance worsens. In this regime, more data hurt the model, unlike in classical learning theory (in which more data always help). Increasing model complexity even more, past this threshold, results in decreasing error once again. Beyond this specific regime, DL models can have billions of parameters and still generalize well. To explain this behavior—called double descent—and the ability of generalization, researchers have developed a theory called implicit regularization, drawing on ideas from various fields including free probability, statistical mechanics, physics, and information theory. In addition to DL in general, Austern described graph representation learning that is used in ML for scientific discovery, where data often have specific structures, which makes UQ difficult. She emphasized that this is another area where theoretical foundations are not well understood.

Austern summarized that modern ML algorithms are so poorly understood because researchers lack the mathematical tools needed to study them. Classical learning theory relies on a few powerful, universal probability theorems that do not extend to modern ML methods. Instead, new mathematics will be needed. She concluded by framing the study of theoretical foundations of ML as an opportunity for all mathematicians—whether from ergodic theory, probability theory, functional analysis, optimization, algebra, or another area—to contribute to better understanding of ML algorithms.

Mathematical Foundations of Machine Learning

To highlight the importance of theory, Willett began by stating that investing in ML without understanding mathematical foundations is like

investing in health care without understanding biology. She asserted that understanding foundations will allow for faster, cheaper, more accurate, and more reliable systems.

Willett first shared success stories of mathematical foundations improving ML practice. She explained that ML often requires training data to set parameters of a model (e.g., NN weights), and parameters are updated in an iterative approach based on an optimization algorithm that minimizes errors, or loss. AdaGrad is an innovation that accelerates training and has strong theoretical foundations. Adam, one of the most popular optimization methods for training ML algorithms, is based on the foundation of AdaGrad. Another example is distributed optimization, in which large-scale ML is distributed across multiple machines. She remarked that in early instances of distributed optimization, naïve methods resulted in slower computation with the use of more machines. Researchers studying the mathematical and theoretical foundations discovered a bottleneck in the communication necessary to keep the different machines in sync. Understanding optimization theory led the community to develop approaches, like Hogwild!, that were theoretically grounded methods for asynchronous distributed optimization, eliminating most of the communication bottleneck and accelerating computation. She noted that data privacy also provides an example of the success of mathematical foundations for practice. The classical approach of aggregate data is a form of privacy that is easy to break, but the more recent innovation of differential privacy, grounded in mathematical foundations, uses random perturbations to better protect privacy. Willett referenced Austern’s mention of conformal inference as a method for UQ of ML algorithms with theoretical guarantees, and she shared a final example from medical image reconstruction, in which knowledge from inverse problem theory aided the creation of new network architectures that can reconstruct CT images from raw data (i.e., sinograms) both more accurately and with less training data.

Willett then addressed some open questions and opportunities in the field of ML’s theoretical foundations. Returning to the basic definition of an NN, she explained that NNs are essentially functions that have some input data and produce an output, depending on learned weights or parameters. One interpretation of training a network is that it is searching over different functions to find the one that fits best. Therefore, she said that thinking about NNs as functions allows researchers to better consider questions such as (1) how much and what data are required, (2) which models are appropriate and how large they should be, (3) how robustness can be promoted, and (4) whether models will work in new settings.

Other questions for the ML field include those of efficiency and environmental impact, Willett noted. Training and deploying large-scale AI

systems are associated with a large carbon footprint, and water is sometimes required to cool computational systems. However, mathematical foundations may help optimize architectures for efficiency. Concerns about AI perpetuating systematic bias also raise questions for the field, she continued, and investing in mathematical foundations can contribute to the design of enforceable and meaningful regulations and certifications of ML systems.

Willett observed that ML is changing the way scientific research is approached, and it will continue to influence hypothesis generation, experimental design, simulation, and data analysis. She cautioned that using AI tools without understanding mathematical foundations may lead to results that cannot necessarily be trusted—citing concerns of a reproducibility crisis in science for this very reason (Knight 2022)—but the combination of ML and scientific research still carries enormous potential. She described four ways that ML and scientific research interact. First, ML could help uncover governing physical laws given observations of a system (see Brunton et al. 2016; Lemos et al. 2022; Udrescu and Tegmark 2020). Despite promising research, significant mathematical challenges remain—such as generalizing to higher dimensions or dealing with sparse or noisy data—and developing mathematical foundations could be especially impactful in this area. Second, ML can be used to better design experiments, simulations, and sensors, and she shared the example of self-driving laboratories that adaptively design and conduct experiments. Third, ML can assist in jointly leveraging physical models and experimental or observational data, as in physics-informed ML. Since work in such areas still lacks mathematical foundations, leaving many open problems, developing foundations can solidify this work. Finally, Willett pointed to how advancing the frontiers of ML can benefit broader science because of the overlap between fields; learning from simulations requires understanding data assimilation and active learning, for example, and studying these benefits both ML research and other sciences. She asserted that investing in the mathematical foundations of ML has the potential to be impactful across different applications and domains.

Discussion

Tao began the discussion by requesting advice for young researchers wishing to contribute to the mathematical foundations of ML. Willett indicated that beyond understanding the basics of linear algebra, statistics, and probability that are fundamental to ML, researchers will need training specific to the kind of work they would like to do. Some areas might require knowledge of partial differential equations and scientific computation, while others might be grounded in information theory or signal

processing. Austern agreed that a strong understanding of the basics should be developed first, and she also suggested that new contributions may come from mathematical areas that have not previously interacted much with ML, such as ergodic theory.

Noting that some areas of theoretical computer science have been driven by major mathematical conjectures, such as P = NP, Tao asked whether ML has comparable mathematical conjectures. Willett observed that ML research has often been driven by empirical observations instead of any mathematical conjectures as concrete as P = NP. Austern agreed, adding that ML is characterized more by the multitude of aspects that are not yet understood rather than as one large question.

Referencing Austern’s explanation that for deep NNs, a regime exists in which more data engender worse performance, Tao inquired as to whether the training protocol should be reconsidered, perhaps starting with smaller datasets instead of using all data simultaneously. Austern specified that the behavior she described occurs in a critical setting and expressed wariness toward changing practices before a full mathematical understanding is developed. Willett shared that a subfield of ML called curriculum learning seeks to train models with easy examples first and then gradually increase complexity. Compelling work is being done, but many interesting open mathematical questions remain, such as what makes an example easy or difficult, or how the process can be made rigorous. She described this as yet another area in ML where researchers are seeking to understand mathematical foundations.

CHALLENGES AND BARRIERS PANEL

The session on challenges and barriers to the adoption of AI for mathematical reasoning concluded with a panel discussion between earlier speakers Jeremy Avigad, Stella Biderman, and Ursula Martin, along with Carlo Angiuli, Carnegie Mellon University. Tao served as the moderator.

Tao began by asking each panelist to discuss the main challenges for the community using AI to assist mathematical reasoning. Explaining that the community is comprised of few tenured professors and more postdoctoral, graduate, and undergraduate students, Avigad identified the main challenge as determining how to create space for the younger people to succeed. No standard path exists yet for young researchers in this area, so the main challenge is institutional. Martin seconded this sentiment and noted that external funding is a particularly powerful motivator for academic research. She also raised the challenge of integrating new mathematical tools into the research pipeline, and she suggested a potential solution in learning from other disciplines that have adapted to new technologies. Sharing her perspective as an AI researcher,

Biderman stated that AI researchers generally do not know what would be helpful to mathematicians, which creates a barrier to technological advancements. Angiuli added that a future challenge to grapple with, beyond the collaboration of mathematicians and AI researchers, is how to create tools that mathematicians can use without direct, constant collaboration with AI researchers—essentially, how AI can become part of mathematics itself.

The speakers continued to discuss the institutional challenges facing the field of AI for mathematical reasoning. Angiuli observed that currently, work in mathematical formalization can generally only be published in computer science venues and not mathematics journals. This work, which lies at the intersection of fields, is not yet widely recognized as mathematics; interdisciplinary work often faces this struggle. Biderman turned the discussion toward the incentive structure in mathematics, emphasizing the importance of the metrics that departments consider when evaluating researchers. She pointed out that AI researchers easily amass thousands of citations, but that milestone may not be of any importance in mathematics. Avigad confirmed that mathematics departments value the specific journals in which a person publishes and not the number of citations, and Biderman responded by emphasizing how different the metrics are between mathematics and computer science. Martin asserted that changing this incentive structure may require a top-down approach from high-level leadership and noted the political dimension to the issue. Tao summarized that there seems to be a promising trend in which the definition of mathematics is broadening, and hopefully the culture will continue to change.

Tao shared a workshop participant’s question about the drastic shift of researchers from public to private institutions, especially corporations, due to the large sums of money required to train AI models. Acknowledging the gravity of the issue, Biderman said that this shift is a matter of expertise in addition to money, because usually only select corporations (and not universities) have the ability to teach new researchers how to train large models. Avigad agreed with the concern, citing the university as the primary home of mathematics, where people have the freedom to explore ideas without focusing on applications. He stressed the importance of ensuring that universities have the necessary resources for mathematicians. Angiuli asked Biderman whether the financial issue is a matter of funding in industry versus academia. Biderman answered that the issue is about the political willingness to spend rather than about a lack of funding; winning grants for large-scale academic AI research is difficult. In response to another workshop participant’s question about where funding for interactive theorem proving can be found, Biderman named Google in addition to Microsoft, as well as the Defense Advanced

Research Projects Agency. She reiterated that finding funding for interactive theorem proving can be challenging.

One workshop participant voiced concern that graduate students in pure mathematics usually have a limited coding background compared to computer science students and asked for suggestions for such students to engage with AI tools. Avigad countered that young mathematicians are becoming increasingly skilled in coding as computers are built into ways of thinking, and he also suggested that anyone interested in formalization can find endless resources and support online—for example, starting with the Lean community.6 Angiuli, Biderman, and Martin all agreed that learning to code is important for mathematics students and should be pursued. Biderman indicated that students could start with smaller AI models that require less expertise, but above all she urged mathematics students to take introductory computer science courses and learn Python.

Workshop planning committee member Talia Ringer, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, expressed that collaborating with AI researchers can be intimidating because of how large and powerful the community is, and one often ends up needing to work on their terms. Ringer wondered about ways to address this power dynamic. Stressing that this is a difficult question, Martin observed that any given collaboration will be with individuals and not the entire community. Collaboration is social; finding the right collaborator can take a long time, she continued, and one can learn from collaborating with the wrong people. Avigad added that crossing disciplinary boundaries is one of the main challenges in this work. Research includes a large social component, and communication between mathematicians and computer scientists can be awkward because of the differences in communities: different mindsets, expectations, and ways of thinking and talking. Martin agreed, explaining that this dynamic is why collaboration takes time. Biderman added that many AI researchers do not know exactly what mathematicians do, or what distinguishes mathematical thinking and proof, so events like this workshop help break that barrier by spreading awareness and promoting connections for smoother collaboration. She also pointed out that much of the large-scale AI research that is not conducted at large technology companies occurs on Discord, between “random people on the Internet.” These communities do high-quality work out of passion and interest, and she asserted that many places exist to find collaborators who are not from large, powerful companies.

Stating that the world is currently in the century of computer science, workshop planning committee chair Petros Koumoutsakos asked about

___________________

6 The Lean theorem prover website is https://leanprover.github.io, and the Lean community website is https://leanprover-community.github.io, both accessed July 26, 2023.

reasons for computer scientists to engage with mathematics. Citing that AI research is concerned with various applications, Biderman observed that computer scientists often engage with other domains, and many researchers find the application of AI to mathematics inherently interesting. Avigad emphasized the benefits of any opportunities for the fields to come together, and Angiuli added that verifying software is a natural place for the domains to meet. Biderman also noted the historical overlap between AI research and theoretical computer science, and she indicated that collaboration between AI and mathematics could build on those experiences.

Another question sparked discussion of the ethical issues involved when researching the interplay of AI and mathematical reasoning. Martin highlighted potential ethical issues of bias in the training of models, and Biderman highlighted similar issues in model development. Biderman stated that compared to many other applications of AI, fewer opportunities exist for ethical issues in AI for mathematics. AI technologies for identifying people in videos, for example, have been used by oppressive regimes to surveil their citizens or in the United States to aid police arrests. AI for pure mathematics does not carry these kinds of dangers of accidentally contributing to oppressive systems, she continued. However, Angiuli observed that as the mathematics community is comprised of people, potential issues could still arise from the interfacing between the abstract mathematics and the people who lead and are part of the community. Biderman qualified that the area is not devoid of ethical issues, but the moral hazard is lower when compared with other fields like natural language processing that commonly have certain classes of ethical issues. Sharing a related anecdote, Tao mentioned G.H. Hardy, who took pride working in number theory because of its lack of potentially dangerous applications and was then horrified when it became fundamental to cryptography, which has many military applications. Angiuli pointed out that plenty of funding for software and hardware verification research comes from the Department of Defense—for example, to verify unmanned drones.

The session concluded with a discussion of how progress in using AI for mathematical reasoning is made and measured. Avigad asserted that mathematicians will value the use of AI on any traditionally recognized mathematical problem; the question is what mathematical questions AI will be able to succeed in solving, and finding the answer will require trial and error. Biderman noted a symmetry in that researchers can use mathematics to advance AI and use AI to advance mathematics; the two are closely intertwined and grow together.

REFERENCES

Al Roumi, F., S. Marti, L. Wang, M. Amalric, and S. Dehaene. 2021. “Mental Compression of Spatial Sequences in Human Working Memory Using Numerical and Geometrical Primitives.” Neuron 109(16):2627–2639.

Amalric, M., L. Wang, P. Pica, S. Figueira, M. Sigman, and S. Dehaene. 2017. “The Language of Geometry: Fast Comprehension of Geometrical Primitives and Rules in Human Adults and Preschoolers.” PLoS Computational Biology 13(1):e1005273.

Austern, M., and W. Zhou. 2020. “Asymptotics of Cross-Validation.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.11111.

Azerbayev, Z., B. Piotrowski, H. Schoelkopf, E.W. Ayers, D. Radev, and J. Avigad. 2023. “Proofnet: Autoformalizing and Formally Proving Undergraduate-Level Mathematics.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.12433.

Brunton, S.L., J.L. Proctor, and J.N. Kutz. 2016. “Discovering Governing Equations from Data by Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamical Systems.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113(15):3932–3937.

Collins, K.M., A.Q. Jiang, S. Frieder, L. Wong, M. Zilka, U. Bhatt, T. Lukasiewicz, et al. 2023. “Evaluating Language Models for Mathematics Through Interactions.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.01694.

First, E., M.N. Rabe, T. Ringer, and Y. Brun. 2023. “Baldur: Whole-Proof Generation and Repair with Large Language Models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.04910.

Gowers, T. 2009. “Is Massively Collaborative Mathematics Possible?” January 27. https://gowers.wordpress.com/2009/01/27/is-massively-collaborative-mathematics-possible.

Jiang, A.Q., S. Welleck, J.P. Zhou, W. Li, J. Liu, M. Jamnik, T. Lacroix, Y. Wu, and G. Lample. 2022. “Draft, Sketch, and Prove: Guiding Formal Theorem Provers with Informal Proofs.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.12283.

Knight, W. 2022. “Sloppy Use of Machine Learning Is Causing a ‘Reproducibility Crisis’ in Science.” Modified August 10, 2022. https://www.wired.com/story/machine-learningreproducibility-crisis.

Lemos, P., N. Jeffrey, M. Cranmer, S. Ho, and P. Battaglia. 2022. “Rediscovering Orbital Mechanics with Machine Learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.02306.

Lewkowycz, A., A. Andreassen, D. Dohan, E. Dyer, H. Michalewski, V. Ramasesh, A. Slone, et al. 2022. “Solving Quantitative Reasoning Problems with Language Models.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35:3843–3857.

Mishra, S., M. Finlayson, P. Lu, L. Tang, S. Welleck, C. Baral, T. Rajpurohit, et al. 2022. “Lila: A Unified Benchmark for Mathematical Reasoning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.17517.

Pease, A., and U. Martin. 2012. “Seventy Four Minutes of Mathematics: An Analysis of the Third Mini-Polymath Project.” Proceedings of AISB/IACAP 2012.

Sablé-Meyer, M., J. Fagot, S. Caparos, T. van Kerkoerle, M. Amalric, and S. Dehaene. 2021. “Sensitivity to Geometric Shape Regularity in Humans and Baboons: A Putative Signature of Human Singularity.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118(16):e2023123118.

Udrescu, S., and M. Tegmark. 2020. “AI Feynman: A Physics-Inspired Method for Symbolic Regression.” Science Advances 6(16):eaay2631.

Wang, L., M. Amalric, W. Fang, X. Jiang, C. Pallier, S. Figueira, M. Sigman, and S. Dehaene. 2019. “Representation of Spatial Sequences Using Nested Rules in Human Prefrontal Cortex.” NeuroImage 186:245–255.

Welleck, S., J. Liu, X. Lu, H. Hajishirzi, and Y. Choi. 2022. “Naturalprover: Grounded Mathematical Proof Generation with Language Models.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35:4913–4927.

Wiles, A. 1997. “The Proof.” PBS, October 28. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/transcripts/2414proof.html.

Zheng, K., J.M. Han, and S. Polu. 2021. “MiniF2F: A Cross-System Benchmark for Formal Olympiad-Level Mathematics.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.00110.