Long Freight Trains: Ensuring Safe Operations, Mitigating Adverse Impacts (2024)

Chapter: 2 Overview of Long Train Safety Challenges and Performance

2

Overview of Long Train Safety Challenges and Performance

While long trains are not new to the freight railroad industry, this chapter explains the significance of recent changes in the type and operation of long trains, and particularly the increasing length of manifest trains. Previously, the longest trains operated by railroads were disproportionately unit trains, and hence past research on the safety performance of long trains did not address manifest trains explicitly. The chapter therefore begins with a brief history of long trains and the recent technological developments that have enabled railroads to operate longer manifest trains.

The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) of the United States and the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) of Canada have raised concerns in safety advisories about the safe operations of longer manifest trains.1,2 The chapter explains the reasons for these concerns and then presents analysis of FRA derailment data to see if there is evidence of these concerns affecting rail safety. Because the handling challenges associated with long trains is called out in FRA safety advisories, consideration is given to railroad practices for train makeup, which is critical for managing in-train forces.

___________________

1 FRA (Federal Railroad Administration). 2023. “Safety Advisory 2023-03; Accident Mitigation and Train Length.” Federal Register, May 2. https://railroads.dot.gov/sites/fra.dot.gov/files/2023-05/Safety%20Advisory%202023-03.pdf. See also FRA. 2023. “Safety Advisory 2023-02; Train Makeup and Operational Safety Concerns.” Federal Register, April 11. https://railroads.dot.gov/elibrary/safety-advisory-2023-02-train-makeup-and-operational-safety-concerns.

2 Transportation Safety Board of Canada. 2020. “Managing In-Train Forces.” Rail Safety Advisory Letter 617-06/20. Ottawa, ON: Transport Canada.

The chapter concludes by reviewing the role of safety management systems (SMSs) in addressing new or heightened safety challenges that longer trains may present. FRA requires that railroads institute Risk Reduction Programs (RRPs), which if consistent with the standard elements of a fully developed SMS program would be expected to address such safety-related challenges in a deliberate and systematic manner. However, FRA’s RRP requirements and compliance audits are (in FRA’s words) “streamlined,” and as a result, it is unclear whether railroads are being deliberate and systematic in controlling the risks from longer trains.3

TREND TOWARD LONGER MANIFEST TRAINS

According to the Association of American Railroads (AAR), long unit trains have been operating in some fashion for more than 80 years. Trains with 180 or more cars have been used on a limited set of routes to move iron ore and coal since as early as the 1940s.4 The placement of locomotives at intervals throughout the train to provide distributed power (DP) helped mitigate high in-train draft forces, which, along with the development of stronger coupler systems, allowed railroads to operate 120-car (or more) unit trains on a more widespread basis as early as the 1960s. The DP units were controlled remotely by the crew in the lead locomotive. More recently, the introduction of alternating current (AC) traction locomotives allowed trains to high throttle indefinitely without overheating (in contrast to locomotives equipped with direct current [DC] traction motors). Because AC traction increases adhesion and low-speed tractive effort, the use of these motors allowed railroads to operate longer and heavier trains in more locations, especially on mountain grades.5 Although most of these technological advances were applied to increase the length of unit trains, AAR reports that even by the 1960s some railroads were experimenting with longer manifest trains, notably the Southern Railway.6

During the 1990s, some railroads began implementing Precision Scheduled Railroading (PSR) that emphasizes freight trains in point-to-point service operating on fixed schedules, instead of being dispatched whenever sufficient loaded cars are available. While it is pursued and

___________________

3 Federal Register 85(32):9273, February 18, 2020.

4 AAR presentation to committee, January 2023.

5 PRC Rail Consulting Ltd. “Electric Traction Control.” http://www.railway-technical.com/trains/rolling-stock-index-l/train-equipment/electric-traction-control-d.html (accessed June 4, 2024).

6 AAR presentation to committee, January 2023.

TABLE 2-1 Origins of Precision Scheduled Railroading by Railroad

| Railroad | Year |

|---|---|

| Canadian National Railway | 1998 |

| Canadian Pacific | 2012 |

| CSX Transportation | 2017 |

| Union Pacific Railroad Company | 2018 |

| Kansas City Southern | 2019 |

| Norfolk Southern Railway | 2019 |

SOURCE: GAO Analysis of Class I Freight Railroad materials, data from the Bureau of Transportation Statistics on freight volumes, and analysis by Council of Economic Advisors – GAO-23-105420.

defined differently by the Class I railroads, PSR’s aim, as a general matter, is to increase operating efficiency and reduce labor and fuel costs.7,8

As shown in Table 2-1, PSR has been adopted by all but one (BNSF) of the major railroads. A 2023 study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that the adoption of PSR has consistently led to longer trains, decreases in the number of assets such as locomotives, and reductions in the railroad workforce.9 According to GAO, between 2011 and 2021, the number of Class I service locomotives decreased by 5%, the number of service rail cars decreased by 32%, and the number of railroad workers decreased by 28%.10

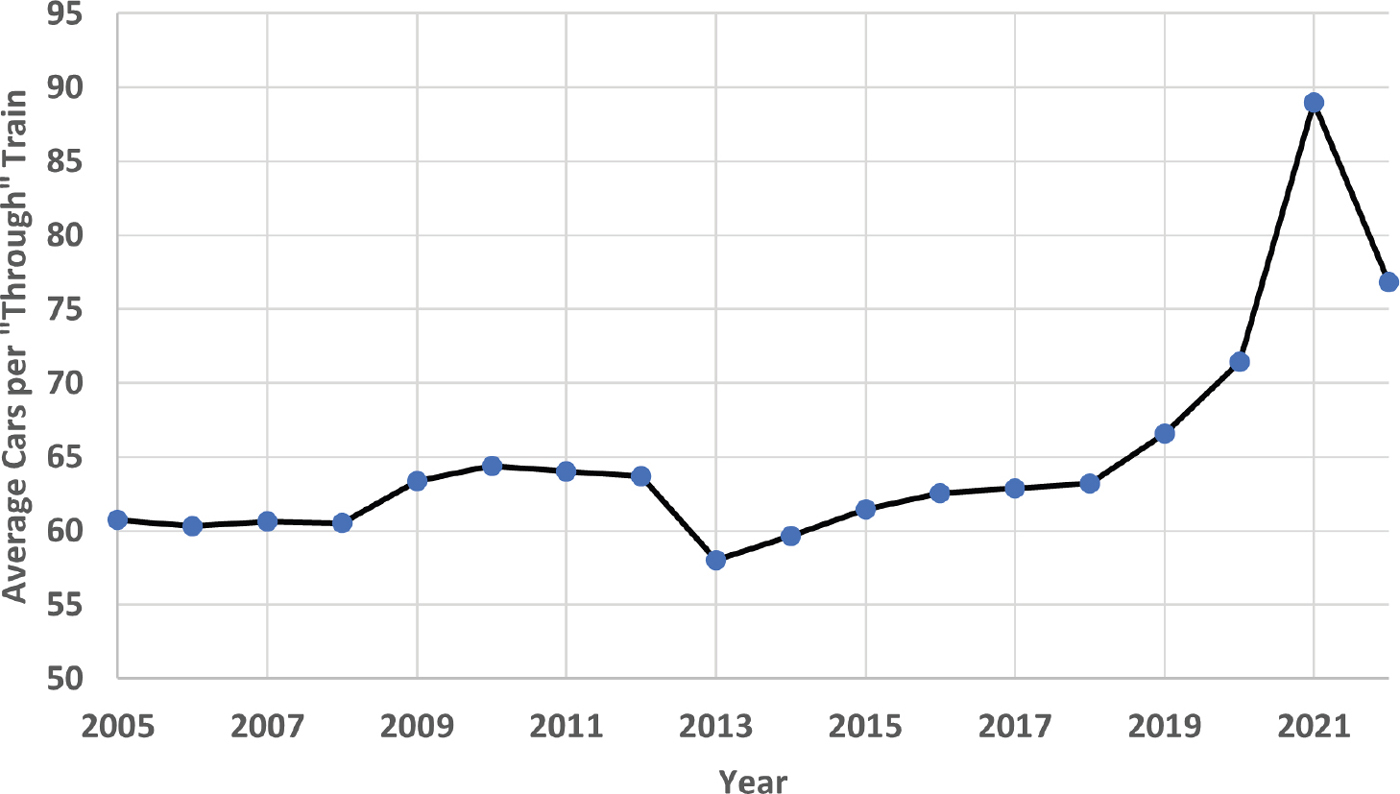

Although PSR does not necessarily require long trains, most Class I railroads began to show a substantial increase in the average length of their long-distance “through” trains as they shifted to PSR. Through trains operate between two or more major concentration or distribution points (i.e., rail yards and terminals), as opposed to trains used for local services or unit trains. Whether PSR is the main cause of longer manifest trains is unclear; however, Figure 2-1, which is derived from annual reports (R-1) submitted by railroads to the Surface Transportation Board (STB), shows that the average size of through trains, measured by number of cars, has increased in

___________________

7 Dick, C.T. 2021. “Precision Scheduled Railroading and the Need for Improved Estimates of Yard Capacity and Performance Considering Traffic Complexity.” Transportation Research Record 2675(10):411–424.

8 GAO (U.S. Government Accountability Office). 2023. “Freight Rail: Information on Precision-Scheduled Railroading.” https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105420.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

NOTE: Data are for Union Pacific Railway, Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway (BNSF), Norfolk Southern Railway, and CSX Transportation Railway (CSX).

SOURCE: Surface Transportation Board (STB) R-1 reports.

recent years among the four largest Class I railroads.11 The STB R-1 data do not allow for direct estimates of average train length, and thus the number of rail cars per train is used as a proxy for train length. While average rail cars per through train remained fairly stable from 2005 to 2018, the average grew to 89 in 2021 and 77 in 2022.

It merits noting that while STB’s definition of through trains excludes local and unit trains, it does include both manifest and intermodal trains and the data cannot be disaggregated further. While manifest and intermodal trains differ in a number of respects, they do share the same characteristic of having cars of different lengths, weights (empty, loaded), and configurations. Moreover, some intermodal trains are filled out with automobile carriers and other conventional rail cars, making them a type of manifest train in these cases.

For the purposes of observing trends in average cars per through train as a proxy for average length of through trains, the aggregation of manifest and intermodal trains is problematic only in the sense that it is likely

___________________

11 Average number of rail cars for a specific year is calculated from dividing annual through car-miles by annual through train-miles from the STB R-1 annual report for an individual railroad during a given year.

to lower the average and suggest that through trains are shorter than they really are. This is because intermodal trains are usually composed of a relatively small number of long, multi-platform articulated rail cars (i.e., 5-unit well cars). Accordingly, a 25-car intermodal train consisting of 5-unit well cars can be the same length as a 125-car manifest train. Thus, if intermodal trains could be removed from the STB data for through trains, this would likely increase the average number of cars (as shown in Figure 2-1), but it would not affect the overall pattern of change unless the proportion of intermodal and manifest trains was changing significantly.

INDICATIONS OF THE SAFETY PERFORMANCE OF LONGER TRAINS FROM DERAILMENT DATA

All six Class I railroads presenting to the committee maintained that the operation of longer trains should result in safer train operations and fewer derailments overall. The six railroads maintained that longer trains result in fewer trains in total, and therefore fewer opportunities for derailments.12 Furthermore, the railroads maintained that the frequency of equipment-caused and track-caused derailments should be unaffected by train length.13

Despite these assertions, both FRA and TSB have raised concerns in safety advisories about operational and handling challenges associated with longer manifest trains.14,15 During March and April 2023, FRA issued advisories on accident mitigation and train length, train makeup, and operational safety. The advisories followed the initial investigations of the derailment of a 9,300-ft-long manifest train in East Palestine, Ohio, and subsequent derailments in Springfield, Ohio; Ravenna, Ohio; and Rockwell, Iowa, all of which involved trains that were more than 12,000 ft long.

According to FRA’s advisory, these manifest train derailments “demonstrate the need for railroads and railroad employees to be particularly mindful of the complexities of operating longer trains, which include, but are not limited to (1) train makeup and handling; (2) railroad braking and train handling rules, policies, and procedures; (3) protecting against the loss of end-of-train (EOT) device communications; and (4) where

___________________

12 Class I railroad presentations to committee, January, March, and April 2023.

13 Ibid.

14 FRA. 2023. “Safety Advisory 2023-03; Accident Mitigation and Train Length.” Federal Register, May 2. https://railroads.dot.gov/sites/fra.dot.gov/files/2023-05/Safety%20Advisory%202023-03.pdf. See also FRA. 2023. “Safety Advisory 2023-02; Train Makeup and Operational Safety Concerns.” Federal Register, April 11. https://railroads.dot.gov/elibrary/safety-advisory-2023-02-train-makeup-and-operational-safety-concerns.

15 Transportation Safety Board of Canada. 2020. “Managing In-Train Forces.” Rail Safety Advisory Letter 617-06/20. Ottawa, ON: Transport Canada.

applicable, protecting against the loss of radio communications among crew members.”16

The TSB advisory raised similar concerns related to the length and weight of longer trains by stating that

with the increase in average train length and weight, there have been increases in the associated in-train forces. Longer trains in particular can generate significant longitudinal draft/buff forces due to the slack action of the train. To minimize these draft/buff forces requires more critical management of freight car placement (train marshalling) within the trains to reduce in-train forces and maintain safe operations.17

In these safety advisories, FRA and TSB identified a number of operational concerns related to longer manifest trains, including concerns about the effects of greater in-train forces and the importance of sound train makeup procedures to account for these forces. The advisories also raised issues pertaining to train handling and braking, communications among crew members, and communications between the locomotive cab and EOT device.

Before considering these specific matters, the next section reviews train derailment data and evidence from the literature for insights on how increases in manifest train length may be affecting derailment frequency and severity. Consideration is given first to the derailment performance of manifest trains generally when compared to unit trains. This is followed by references to past studies that have examined how train length correlates with the frequency and severity of derailments. As noted above, FRA’s advisories have pointed to the handing challenges that longer manifest trains can create because of the mix of rail cars in the consist. With these concerns in mind, FRA accident data are examined to see if rates of derailments (per ton-mile) involving train makeup and handling deficiencies have been changing in relation to upward trends in average train size (i.e., number of cars per train).

Derailment Performance of Manifest Trains Generally

Although train type is not always cited in aggregate statistics of derailment patterns and trends, it is important to assess and understand. For instance, Zhang et al. determined that, for the years 1996 to 2018, manifest trains

___________________

16 FRA. 2023. “Safety Advisory 2023-02; Train Makeup and Operational Safety Concerns.” Federal Register, April 11. https://railroads.dot.gov/elibrary/safety-advisory-2023-02-train-makeup-and-operational-safety-concerns.

17 Transportation Safety Board of Canada. 2020. “Managing In-Train Forces. Rail Safety Advisory Letter 617-06/20. Ottawa, ON: Transport Canada.

exhibited a mainline derailment rate per ton-mile that was 40% higher than the derailment rate for loaded unit trains.18 A major reason for this higher rate appears to be differences in the propensity for train handling errors. Although manifest trains and loaded unit trains exhibited similar rates of derailments for both equipment-caused and track-caused incidents, the derailment rate from human factor causes was more than four times higher for manifest trains.19 This result suggests that manifest trains may pose greater operational and handling challenges for crew members than units trains, despite the latter trains being heavier on average than manifest trains.

The specific reasons for the handling challenges are discussed more below, but they stem from differences in how manifest trains and unit trains are constructed. The former contain a mix of rail car types, sizes, and weights, while the latter are more uniformly constructed, usually consisting of the same types of cars (i.e., tank car, hopper car), each having similar sizes and weights. As a result, the weight, length, truck-center spacing, center of gravity, and coupler draft gear cushioning for individual rail cars can vary greatly in manifest trains compared to the more homogeneous unit trains. The distribution of power will also differ from train to train. Manifest trains will therefore exhibit more variability in their handling requirements, which train crews must be able to recognize and accommodate. By comparison, unit trains are typically a consistent length and locomotive configuration, which allows crews to use consistent and repeatable control methods.

Long Trains and Derailment Frequency and Severity

If train miles and derailment potential are correlated, then the transportation of a fixed amount of freight by long manifest trains displacing shorter manifest trains should reduce total derailments, as maintained by the Class I railroads. However, because longer manifest trains have more cars, the derailments that do occur may be more consequential. The consequences of a train derailment can be characterized by descriptors of the derailment itself, such as the number of rail cars derailed and damaged, and by measures of impacts on railroad workers, local communities, and emergency responders, including the number of people evacuated due to concerns about hazardous materials.

Research on train derailments caused by equipment and mechanical failures shows that the number of cars derailed is correlated to the length

___________________

18 Zhang, Z., C.-Y. Lin, X. Liu, Z. Bian, C.T. Dick, J. Zhao, and S.W. Kirkpatrick. 2022. “An Empirical Analysis of Freight Train Derailment Rates for Unit Trains and Manifest Trains.” Journal of Rail and Rapid Transit 236(10):1168–1178. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544097221080615.

19 Ibid.

of the derailed train.20 Furthermore, the literature shows that the number of cars derailed is highly correlated with the likelihood of hazardous materials being released and other severe outcomes.21,22,23

Trends in Derailment Rates and Average Train Size

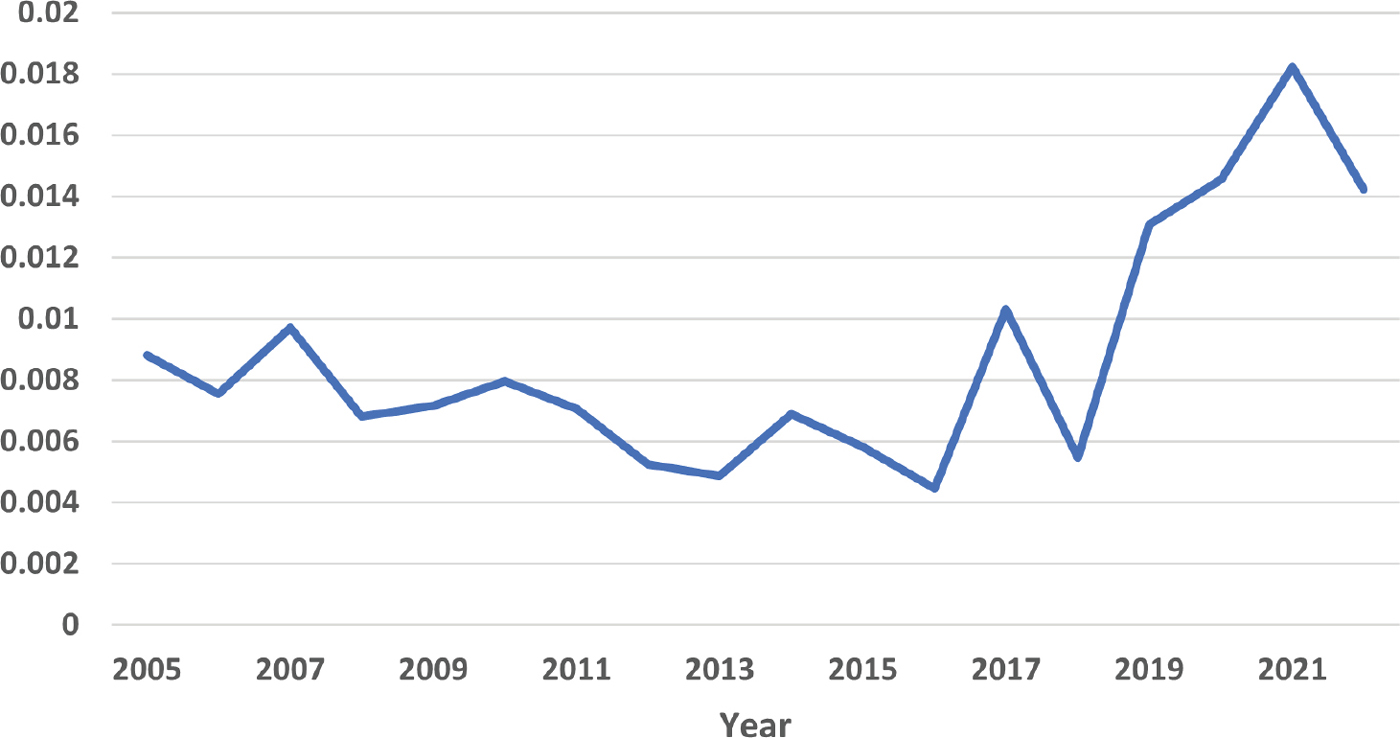

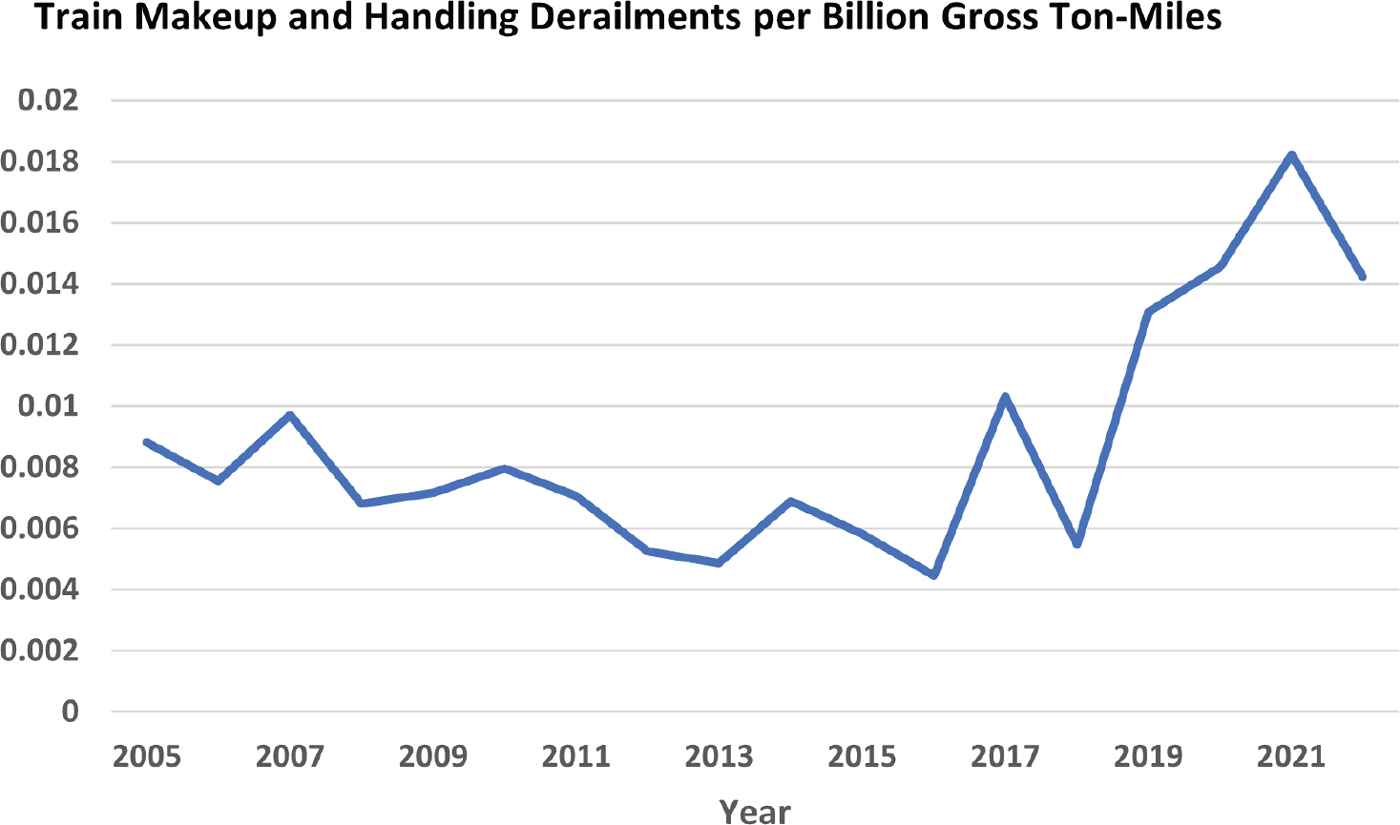

The following is an analysis of derailments of freight trains occurring from 2005 to 2022 and focusing on the experience of the four largest Class I railroads (BNSF, CSX, NS, and UP). The aim of the analysis is to see if there is an association between the average size of through trains, as defined earlier for Figure 2-1, and rates of freight train derailments attributed to train makeup and handling issues as identified in FRA accident records.24 The analysis uses STB data (from annual R-1 reports) on the annual gross ton-miles of the four Class I railroads to calculate derailment rates.25

To focus on derailments that can be attributed to train makeup and handling issues, only mainline derailments with the FRA causal codes listed in Table 2-2 were selected. These codes include a preponderance of human-related causes, such as excessive buff and draft forces due to improper train handling, and some equipment-related causes, such as broken knuckles and drawbars. FRA and TSB have pointed to such issues in their safety advisories pertaining to longer manifest trains, as noted above.

Figure 2-2 shows the annual derailment rates from 2005 to 2022 calculated by combining mainline derailments caused by train makeup and handling issues and then dividing their sum by the total gross ton-miles for the four Class I railroads combined. The trendline shows marked increases in the annual rate of these derailments starting in 2019.

Having observed an increase in the rate of occurrence of derailments associated with train makeup and handing issues, a matter of interest is

___________________

20 Schafer, D.H., and C.P.L. Barkan. 2008. “Relationship Between Train Length and Accident Causes and Rates.” Transportation Research Record 2043(1):73–82. https://doi.org/10.3141/2043-09.

21 Nayak, P.R., and D.W. Palmer. 1980. “Issues and Dimensions of Freight Car Size: A Compendium.” Report No. FRA-ORD-79/56. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration.

22 Barkan, C.P.L., C.T. Dick, and R.T. Anderson. 2003. “Analysis of Railroad Derailment Factors Affecting Hazardous Materials Transportation Risk.” Transportation Research Record 1825:64–74.

23 Wang, B.Z. 2019. “Quantitative Analyses of Freight Train Derailments.” Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL.

24 FRA Train Accident Database. 2023. https://data.transportation.gov/Railroads/Rail-Equipment-Accident-Incident-Data-Form-54-Subs/byy5-w977/about_data.

25 STB (Surface Transportation Board). 2023. R-1 Annual Reports: 1996–2022. https://www.stb.gov/reports-data/economic-data/annual-report-financial-data.

TABLE 2-2 Freight Train Derailment Causes Considered in the Analysis

| Codes | Description |

|---|---|

| E30–E34 | Broken or defective knuckles, couplers, drawbars, and draft gear |

| H018–H022 | Improper hand brake application to secure engines and cars |

| H501–H502 | Improper train makeup at and between terminals |

| H503–H504 | Excessive buff or slack action due to train handling, train makeup |

| H505–H507 | Improper train handling on curves |

| H510–H514 | Improper automatic brake application |

| H517–H521 | Improper dynamic brake application |

| H522–H524 | Improper throttle application |

| H599 | Other causes relating to train handling or makeup |

SOURCES: FRA Derailment Cause Codes: Train Operation, Human Factors. https://railroads.dot.gov/forms-guides-publications/guides/appendix-c-train-operation-human-factor. Mechanical and Electrical Failures. https://railroads.dot.gov/forms-guides-publications/guides/appendix-c-mechanical-and-electrical-failures.

SOURCE: STB R-1 reports and FRA accident reports.

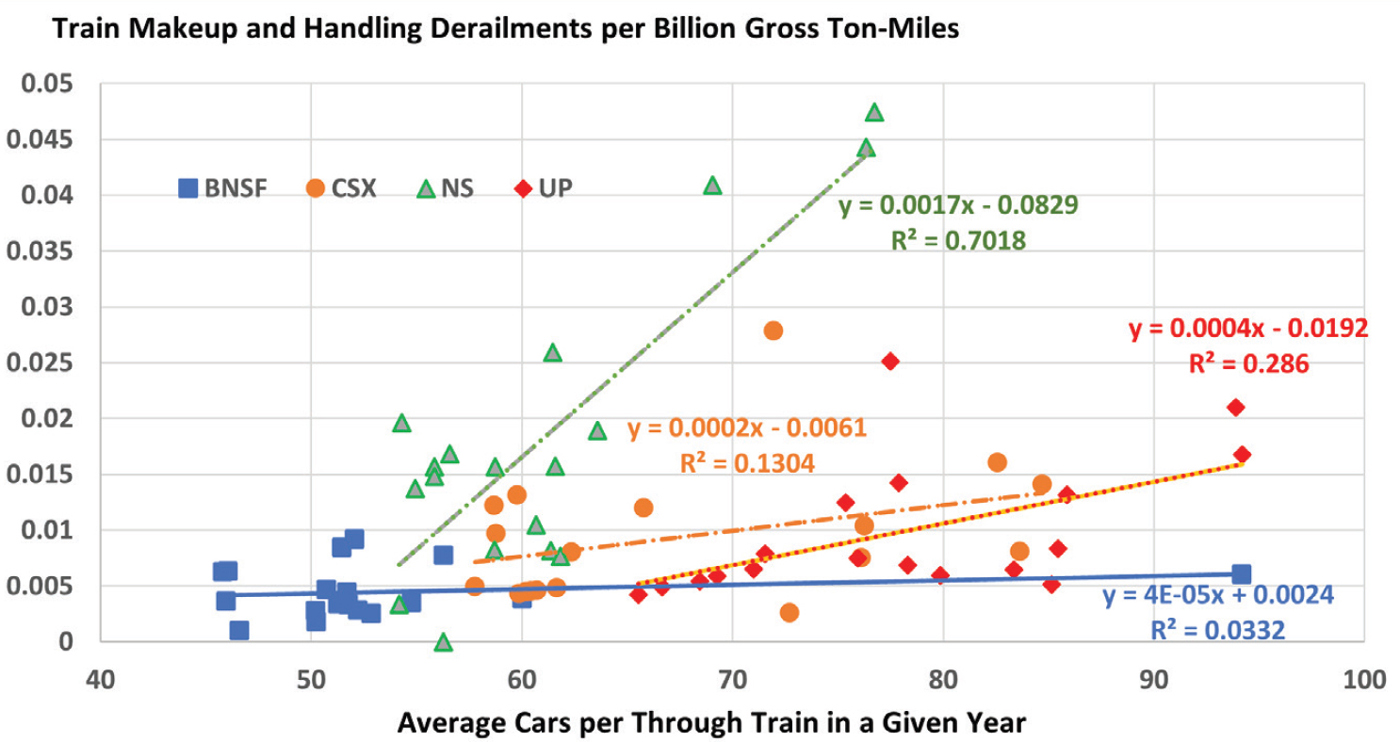

whether this pattern aligns with changes in average through train size. Thus, to take the analyses a step further, Figure 2-3 plots the annual train derailment rates (from makeup and handling issues) for each of the four Class I railroads against each railroad’s average number of cars per through train during 2005 to 2022. Each plotted point represents a Class I railroad for a given year (18 years × 4 Class I railroads = 72 points). The average number of cars per through train is calculated in the same manner as described in Figure 2-1. For reasons explained in discussing that figure, the through train data include intermodal trains in addition to manifest trains, but this aggregation should not be problematic because the inclusion of intermodal trains is likely to depress the calculated average number of cars per train.

A linear regression trendline of the plotted values reveals a positive relationship between increasing rates of derailments (from handling and makeup issues) and average number of cars per through train. The chances of there not being a positive relationship, after testing for the p-value of the linear equation’s slope coefficient, is much less than 1%.26

Figure 2-4 shows the same plotted points but identifies the railroads and separates them for trend analysis. While a positive relationship between derailment rates (from train makeup and handling issues) and average through train size is observed for all four railroads, one railroad (NS) stands out as accounting for most of the highest annual derailment rates (11 of the 16 highest rates) while exhibiting the strongest relationship between average through train size and derailment rates. This suggests that railroads may differ in the degree to which they are controlling for the operational challenges associated with increases in manifest train length. These controls, however, may not be fully effective, as the likelihood of train size and derailment rates not having a positive relationship is less than 1% for the regressions performed on data for all four railroads (based on the p-value for the coefficient of the dependent variable in each regression equation).27 The next section describes in more detail the operational challenges that railroads operating longer trains need to address.

IN-TRAIN FORCES AND TRAIN MAKEUP PRACTICES

This section explains how in-train forces create handling challenges for manifest trains and why proper train makeup can be critical to ensuring safe operations. The guidance available to railroads for train makeup is then reviewed.

___________________

26 The x coefficient p-value is 7.07e-16. A p-value of less than 0.05 is typically indicative of a statistically significant relationship.

27 The x coefficient p-values are as follows: NS (4.95e-7), CSX (1.82e-6), UP (2.41e-6), and BNSF (2.60e-7).

NOTE: Each of the 72 plotted points is for one of the four major Class I railroads for a given year, 2005 to 2022.

SOURCE: STB R-1 reports and FRA accident reports.

NOTE: Each of the 72 plotted points is for one of the four major Class I railroads for a given year, 2005 to 2022.

SOURCE: STB R-1 reports and FRA accident reports.

In-Train Forces

In-train forces are created by compressive and stretching forces applied to the cars and their components. Forces that act longitudinally are referred to as “buff” and “draft” forces. Trains traveling on straight track generate steady-state longitudinal in-train forces.28 Buff forces compress cars while draft forces stretch the train. On ascending track, trains generate draft forces, with the magnitude determined in part by trailing tonnage, locomotive tractive effort, and the ascending grade percent. On descending grades, buff forces are generated, with the magnitude determined by the use of dynamic and air brakes, trailing tonnage, and the grade of the track. On undulating track, a train may experience both forces at the same time in different locations on the train.29

Buff forces create the potential for derailments from cars jackknifing while draft forces create the potential for derailments from cars stringlining in curves. Jackknifing occurs when high buff forces push cars against one another, causing wheels on the affected cars to climb the rail (usually on the outside rail on a curve), or the force may cause a rail to roll over if the track is not sufficiently anchored. Stringlining occurs when a train under draft conditions straightens out on a curve, causing lateral forces on two ends of a car to pull the car toward the low rail, which can cause the wheel on the high rail to derail. Additionally, if these longitudinal forces applied to couplers and their components are too high, a train will pull apart (usually as a result of a knuckle failure) and may also cause a derailment.30

Often the effects of these in-train forces are most severe on curved track, with tight curves being the most affected. On curved track, the in-train forces are transferred tangentially to the curve; each coupler forms an angle, and the in-train forces are partially transferred laterally. Coupler lateral forces are transferred to the car bodies and into the trucks and wheelsets, which causes wheels to apply lateral forces to the rail.

In a train with head-end locomotive power only, in-train forces will increase with train length and trailing tonnage.31 High trailing tonnage creates higher in-train forces when locomotives are pulling (draft) and when

___________________

28 FRA. 2005. “Safe Placement of Train Cars: A Report.” June. https://railroads.dot.gov/elibrary/safe-placement-train-cars-report.

29 Ibid.

30 Knuckles are designed to be the weak link in a train that breaks when forces are too high. This prevents more serious damage to cars. However, such breaks often result in undesired emergency air brake applications (explained later in Chapter 5) that can cause derailments.

31 Government of Canada National Research Council. March 31, 2015. “Industry Review of Long Train Operation and In-Train Force Limit - NRC Publications Archive.” https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=bcc92202-14a8-476b-9500-5a384c4ff003.

brakes are not applied uniformly (buff or draft).32,33 Thus, to help mitigate in-train forces, railroads operate DP locomotive units, or locomotives distributed at multiple locations in the train.34 The DP locomotives apply tractive and braking forces through commands sent by radio signal from the lead controlling locomotive. The DP units also help control in-train forces through additional power and dynamic braking.35

Proper train makeup, or marshalling, can help control the magnitude of in-train forces. While train makeup for the purpose of controlling in-train forces is less of a factor for unit and intermodal trains whose cars have uniform cargoes, sizes, and weights,36 it is critical for manifest trains.37 Manifest trains have cars and blocks of cars that vary greatly in weight, length, and other characteristics, such as coupler and cushioning arrangements, that can make train handling more difficult.38 In particular, poor placement of empty cars and cars with end-of-car cushioning (EOCC) devices can cause in-train forces that are excessive enough to cause a derailment.39 Here again, the placement of DP locomotives is critical to mitigate in-train forces by reducing the trailing tonnage for each locomotive. Even though DP locomotives distribute pulling and braking forces throughout the train, they can still create dangerous forces for empty cars immediately ahead of or behind them, which calls for careful placement of the units.40

Train Makeup Protocols and Guidance

When railroads assemble manifest trains, they must consider many factors for managing in-train forces, including

___________________

32 House Transportation and Infrastructure Subcommittee on Railroads, Pipelines, and Hazardous Materials. 2022. “Examining Freight Rail Safety.” June 14. https://www.congress.gov/event/117th-congress/house-event/114882.

33 Serajian, R., S. Mohammadi, and A. Nasr. 2019. “Influence of Train Length on In-Train Longitudinal Forces During Brake Application.” Vehicle System Dynamics 57(2):192–206.

34 AAR (Association of American Railroads). 2023. “Train Makeup Guidance.” Memo. September.

35 Ibid.

36 Train makeup can nevertheless be important for unit trains to separate specific hazardous materials.

37 Ibata, D. 2019. “Train Make-Up 101: Or How to Not Let This Happen to You.” TrainsMag.com, July.

38 FRA. 2023. Safety Advisory 2023-02; Train Makeup and Operational Safety Concerns. D. FRA. Federal Record, GPO. 88:21736.

39 Government of Canada National Research Council. 2024. “Industry Review of Long Train Operation and In-Train Force Limit - NRC Publications Archive.” May 3. https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=bcc92202-14a8-476b-9500-5a384c4ff003.

40 Ibid.

- Limiting trailing tonnage,

- Number of driving (and dynamic braking) axles and total train tonnage,

- Minimum weight requirements for head-end cars,

- Number and placement of empty cars,

- Number and placement of cars equipped with EOCC devices,

- Force limits adjacent to remote locomotives,

- Train length and radio communication, and

- Distributed power unit configuration.41,42

In addition, other factors to be considered include the subdivision (grades and curves), number of and placement of hazardous materials cars, and long-car/short-car combinations.43 When railroads create trip plans for trains, individual cars are usually assembled in blocks by destination, which are then assembled into trains. Some railroads use the position of blocks in a train to control train makeup, whereas others have rules that transcend the placement of blocks, such as positioning heavy cars closer to the front of the consist and lighter cars, cars with EOCC devices, and empty cars toward the rear.44

Locomotive capacity and power capabilities must also be taken into consideration during train makeup. Locomotive power requirements are generally defined by the ruling grade in certain locations.45 Railroads either calculate the horsepower per ton required to maintain the desired speed or calculate the minimum locomotives necessary to haul trains at a minimum continuous speed using either tons per axle46 or some other measure such as haulage capacity factors or locomotive tonnage ratings.

While each railroad has its own rules and instructions to manage in-train forces, they all use industry and internal software to model train operations to create an optimal transportation plan and determine when a particular train or blocking plan may result in excessive in-train forces.47

___________________

41 Transport Canada. 2016. “Marshalling Guidelines for Safe Operations of Freight Trains.” September.

42 Ibata, D. 2019. “Train Make-Up 101: Or How to Not Let This Happen to You.” TrainsMag.com, July.

43 Long cars have long drawbars (couplers) that create excessive lateral forces when coupled to short cars when moving through tight curves or switches.

44 CSX presentation to committee, March 2023.

45 AAR (Association of American Railroads). 2023. “Train Makeup Guidance.” Memo. September.

46 Tons per axle (TPA) is calculated by estimating the trailing tonnage divided by the equivalent powered axles (EPA), or TPA = TT / EPA. For a good reference for train makeup, see Ibata, D. 2019. “Train Make-Up 101: Or How to Not Let This Happen to You.” TrainsMag.com, July.

47 Union Pacific presentation to committee, March 2023.

Certain capacity restraints are estimated based on train rules, subdivision restrictions, available crews, and number of locomotives. The software is used to adjust departure times, align train meets and passes en route, and adjust train sizes accordingly.48 Further adjustments are made along the route to account for changes in schedules, weather conditions, passenger operations, and equipment changes.49 Class I railroads further develop train plans to manage how trains are made up and then operated.50 Some onboard train artificial intelligence technologies “learn” about any changes to the plan en route, while others do not. If train crews receive makeup data that do not match what is in their train order, they notify dispatch to rectify any discrepancies.51

Table 2-3 presents selected rules for CSX, CN, and BNSF, showing how train makeup rules can differ by railroad.

In addition to having different train makeup rules, each railroad has different processes for implementing the rules. Yard and train crews are ultimately responsible for ensuring compliance with the appropriate train makeup protocols for the territory to be traversed prior to the train departing a terminal. On certain railroads, crews are assisted by computer systems that automatically compare the train consist against relevant makeup rules to flag problems. On some railroads, these automated checks only take place at the initial departure terminal, whereas other railroads have implemented systems that check the consist for compliance each time a rail car is added to or set out from the train along the route.

Canadian Pacific Kansas City Railway (CPKC) described a proprietary electronic train area simulation marshalling suite that has been in service for more than 20 years. The software calculates maximum draft and buff forces based on the number, placement, and characteristics of locomotives and location of cars placed in the train. It also evaluates trailing tonnage restrictions behind long and empty cars and ensures L/V (longitudinal over vertical forces) ratios remain below predetermined levels for safe operations.52

Even when utilizing modern freight equipment, draft or buff forces greater than 325,000 to 400,000 lbs can cause damage to cars such as

___________________

48 This software is used for train composition and is different from other software and models that railroads use to determine train makeup and in-train forces.

49 Union Pacific presentation to committee, March 2023.

50 Most/all railroads use some tool to examine existing or future train consists. It was not clear from presentations to the committee that all consists are tested on a real-time basis by all railroads before trains depart yards. The FRA safety advisory of 2023 (previously cited) indicates that current efforts to police train makeup are not universally working.

51 BNSF presentation to committee, May 22, 2023.

52 CPKC presentation to the committee, April 2023.

TABLE 2-3 Selected Train Makeup Rules by Railroad

| Situation | Rule | Railroad |

|---|---|---|

| Manifest trains with single lead locomotive | Must place 5 loaded cars directly ahead of any DP locomotive | CSX |

| First 5 cars in train must not weigh 45 tons or less | CN | |

| Manifest trains with more than one locomotive | Must have 10 loaded cars placed directly ahead of a DP locomotive | CSX |

| First 10 cars in train must not weigh 45 tons or less | CN | |

| DP locomotives | Must have 10 loads placed directly ahead of a DP locomotive | CSX |

| Auto-racks or other cars with end-of-car cushioning devicesa | Must not be placed directly ahead of or behind DP locomotives | CSX |

| DP locomotives | Maximum of 120 cushioned cars in a train | CN |

| Must be placed a minimum of 1,250 ft behind or ahead of any other operating locomotive | CSX | |

| Weight distribution | Maximum of 33% of train weight in the rear quarter of the train | CN |

| Trains without DP locomotives weighing more than 8,000 tons must not have more than 33% of weight in the rear quarter of the train | CSX | |

| Train length and weight restrictions | Maximum of 12,000 ft and 20,000 tons with DP locomotives | CN |

| Maximum of 10,000 ft and 14,000 tons without DP locomotives | CN | |

| Manifest trains longer than 10,000 ft or more than 14,000 tons must not operate without an additional DP locomotive | BNSF |

a To prevent damage to shipments, some cars are equipped with draft gear (couplers) that cushion sudden draft or buff forces for the car. The devices can be hydraulic, or spring loaded. Although the devices cushion the shipment, trains with many of these cars can behave like a giant “Slinky.”

SOURCES: CSX presentation to committee, March 2023; Canadian National Railway (CN) presentation to committee, April 2023; BNSF, presentation to committee, May 2023.

TABLE 2-4 Maximum Knuckle Working Limits

| Knuckle Material Grade | Load at Maximum Permanent Set (lbs) | Ultimate Strength (lbs) |

|---|---|---|

| Grade C (1992) | 250,000 | 300,000 |

| Grade E (1992) | 300,000 | 400,000 |

| AAR MSRP 2010 | 400,000 | 650,000 |

SOURCES: Government of Canada National Research Council. “Industry Review of Long Train Operation and In-Train Force Limit – NRC Publications Archive,” March 31, 2015. https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=bcc92202-14a8-476b-9500-5a384c4ff003.

broken knuckles or couplers in addition to derailments (see Table 2-4).53 Coupler knuckles are designed to be the weak link in a car that will fail before more serious damage results from excessive in-train forces. Knuckles can be replaced by crew members, but a broken knuckle will cause a train separation (and an undesired emergency brake application). CPKC reported that it uses automated train analytics machine learning tools to predict the potential for train separations resulting in undesired emergency brake applications.54

Some areas in North America have mountain grades and challenging terrain. In these locations, several railroads have territory-specific marshalling rules that limit train length and tonnage and marshalling restrictions for problematic car types, including short cars, empty bulkhead flatcars, and cars with EOCC devices such as auto-rack cars.55 Some railroads deploy distributed braking cars, which are modified box cars with air compressors and associated equipment to supplement the train air brake system.56 This can be particularly important in areas with frequent cold temperatures, such as the northern United States and Canada.

Effectiveness of Train Makeup Rules and Policies

The only industry standards for marshalling trains that apply across the North American railroad industry are described in AAR’s “Train Make-up

___________________

53 Government of Canada National Research Council. “Industry Review of Long Train Operation and In-Train Force Limit - NRC Publications Archive,” March 31, 2015. https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=bcc92202-14a8-476b-9500-5a384c4ff003.

54 CPKC presentation to committee, April 2023.

55 CN presentation to committee, April 2023.

56 Ibid. See also CN (Canadian National Railway). 2022. “Distributed Braking Cars Help Keep Our Network Running Safely, Efficiently in Winter.” February 1. https://www.cn.ca/en/stories/20220201-air-cars.

Manual,” published in 1992,57 and the “Marshalling Guidelines for Safe Operation of Freight Trains,” published by Transport Canada in 2016.58 AAR’s “Train Make-up Manual” was one of the first industrywide train makeup manuals that was written to help railroads manage in-train forces through the control of trailing tonnage, the use of head-end and DP locomotives, and the proper placement of critical car combinations in the train. The Transport Canada marshalling guidelines improved and expanded on the trailing tonnage method of AAR’s “Train Make-up Manual” by providing more robust in-train force limits.

The degree to which the railroad train makeup practices are consistent with this guidance and how faithfully the railroads follow their own train makeup procedures is unclear. The derailment trends presented above, and concerns raised in FRA safety advisories, suggest that either more effective rules or more consistent compliance may be needed.59 In Canada, a TSB Safety Advisory Letter from 202060 reported differences in how train makeup is managed by major railroads in the country. For instance, TSB reported one of the two major Canadian railroads performs simulations of every train to minimize in-train forces, while the other uses only general rules of train makeup and has no policies for placement of cars with EOCC devices in a train. The advisory raised concern about the absence in Canada of regulatory requirements for managing in-train forces. Similarly, FRA does not have regulatory standards for managing in-train forces through train makeup formulas or other means.61

___________________

57 AAR. 1992. “Train Make-up Manual.” Report No. R-802. January.

58 Transport Canada. 2016. “Marshalling Guidelines for Safe Operation of Freight Trains.” https://tc.canada.ca/en/rail-transportation/publications/marshalling-guidelines-safe-operation-freight-trains.

59 FRA. 2023. “Safety Advisory 2023-01; Evaluation of Policies and Procedures Related to the Use and Maintenance of Hot Bearing Wayside Detectors.” Federal Register 88:14494–14497. https://railroads.dot.gov/sites/fra.dot.gov/files/2023-03/Safety%20Advisory%202023-01.pdf; FRA. 2023. “Safety Advisory 2023-02; Train Makeup and Operational Safety Concerns.” Federal Register 88:21736. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2023-04-11/pdf/2023-07579.pdf; FRA. 2023. “Safety Advisory 2023–03; Accident Mitigation and Train Length.” Federal Register 88:27570–27573. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2023-05-02/pdf/2023-09239.pdf; National Transportation Safety Board. 2020. “CSX Train Derailment with Hazardous Materials Release, Hyndman, Pennsylvania, August 2, 2017.” https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/RAR2004.pdf.

60 Transportation Safety Board of Canada. 2020. “Managing In-Train Forces: Rail Safety Advisory Letter 617-06/20.” October 1. https://www.tsb.gc.ca/eng/securite-safety/rail/2020/r19t0107/r19t0107-617-06-20.html.

61 “Railroad Operating Rules.” 49 C.F.R. Part 217. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-49/part-217 (accessed May 3, 2024); FRA presentation to committee, January 2023.

Long Trains and Maintaining Safe Track Conditions

As discussed above, higher in-train forces create lateral forces on the rails. These forces can increase rail wear. Lateral forces have the greatest effect on curves. Ideally, the track in curves will be installed to provide superelevation for the track, where one rail is higher than the other to balance the effect of the lateral forces needed to move through a curve at a given speed. Curved track usually has its superelevation set to produce equal wear to the outside and inside rail and to put even load on the high and low rails when the train is traveling at a balanced speed. The design assumes a target train speed. When trains are slower than the target speed, the wear of the inside rail will be increased. When trains are faster, the outside rail will experience more wear.62 While both long and short trains will have these wear impacts, keeping a longer train at the target speed can be more difficult, in part because the train may span multiple curves. Also, longer unit trains with equal truck spacing will put more load for a longer period of time on the curves. Moreover, as train length increases, speed adjustments take longer, and speed restrictions may affect train speed over a longer length of track.63 Except on tangent track, longer trains will have more impacts on the condition of rail infrastructure because train speeds cannot be adjusted to account for the simultaneous and varied impacts of long trains on the different rail geometries.

LONG TRAINS AND SAFETY MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

The increased use of longer trains during the past decade has coincided with FRA’s efforts to ensure that railroads are taking proactive steps, through the use of safety management systems (SMSs), to reduce the risks of their specific operations and conditions, and not simply following the minimum and industrywide standards in FRA regulations and in industry guidance. It is notable that in 2020, after investigating the August 2017 derailment of a long train in Bedford County, Pennsylvania, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) observed the following:64

At the time of the accident, the FRA did not require that each railroad have a risk reduction program (RRP) or system safety program in place.

___________________

62 FRA. n.d. “Mixed Freight and Higher-Speed Passenger Trains: Framework for Superelevation Design.” https://railroads.dot.gov/elibrary/mixed-freight-and-higher-speed-passenger-trains-framework-superelevation-design (accessed May 14, 2024).

63 Dick, C.T., L. Sehgal, C.J. Ruppert, Jr., and S. Gujaran. 2016. “Superelevation Optimization for Mixed Freight and Higher-Speed Passenger Trains.” In Proceedings of the American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association Annual Conference. Orlando, FL.

64 “CSX Train Derailment with Hazardous Materials Release, Hyndman, Pennsylvania, August 2, 2017.” Accident Report NTSB/RAR-20/04 PB2020-101012, p. 34.

That changed on February 18, 2020, when the FRA published a final rule requiring Class I railroads and railroads with inadequate safety performance to submit a written railroad safety RRP to the FRA for review and approval by August 16, 2021 (FR 2020, 9262). Both the first crew and relief crew members expressed concern with operating heavy loads with multiple empty rail cars in the front of the train consist. Although the train makeup was in accordance with CSX rules, NTSB has determined this rule to be insufficient to manage elevated longitudinal forces imparted on blocks of empty rail cars in the front of the train consist.

FRA issued the RRP rule in February 2020, with a staged implementation, to satisfy a statutory mandate in sections 103 and 109 of the Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008 (RSIA).65 NTSB was aware of the new RRP rule and recognized that it did not apply in 2017 when the Bedford County derailment of a long train occurred. Nevertheless, NTSB called on FRA to take active steps to implement the rule in accordance with the RSIA’s emphasis on railroads having deliberate and systematic risk reduction programs for all operational risks. NTSB stated:66

The FRA’s final rule requiring all Class I railroads to develop and implement RRPs represents a departure from the historic approach used by the FRA for oversight and safety management. For example, rather than monitoring rules compliance, an SMS approach seeks to further improve safety through identification and control of potential safety hazards that may not technically violate prescriptive FRA regulations. Transitioning to an RRP regulation will take time to mature for the FRA and industry. The FRA has traditionally had clear minimum safety standards and limited ability to examine the effectiveness of railroad safety programs for hazard identification and management. To date, the FRA has not published guidance for the industry on how to develop and implement the requirements for RRPs and SSPs [safety system programs]. This lack of guidance on what is needed to comply with the FRA’s requirements may result in different levels of RRP and SSP program development and implementation, potentially limiting the safety benefits anticipated from the FRA’s RRP requirement. It is also unclear how the FRA and the industry will measure the success of the required RRPs and SSPs.

NTSB went on to conclude that FRA had not provided sufficient guidance to railroads on how to develop and implement the requirements for an RRP. NTSB recommended that FRA develop and issue guidance for

___________________

65 P.L. 110-432, Division A, 122 Stat. 4848 et seq., codified at 49 U.S.C. 20156 and 20118–20119.

66 “CSX Train Derailment with Hazardous Materials Release, Hyndman, Pennsylvania, August 2, 2017.” Accident Report NTSB/RAR-20/04 PB2020-101012.

railroads to use in developing the RRPs that they were required to submit to FRA for approval.

Historically, most FRA requirements for the rail industry can be characterized as minimum standards, and their compliance is verified and enforced by FRA inspection personnel. For instance, regulations place limits on the wear on an individual component that can be measured by inspectors (i.e., allowable wear on a track component before it must be replaced), or they prescribe certain requirements, such as hours of work and rest, training intervals for safety-critical employees, or inspection intervals for tracks and wheels.67 While such prescriptive and minimum standards are common for safety regulation across all transportation modes, during the past three decades, regulators in many modes and other domains have recognized the importance of supplementing their traditional regulatory regimes with requirements for regulated entities to develop customized SMSs to control the diverse and specific risks arising from the design and operation of their facilities and activities.68,69,70

The four pillars of an SMS are the development and faithful execution of (1) safety policies (including management commitment, accountability, responsibilities, and documentation), (2) safety risk management (including hazard identification, risk assessment, and mitigation), (3) safety assurance (monitoring/measuring, managing change, and continuous improvement), and (4) safety promotion (training, education, and safety communication).71 The idea behind the promotion of these systems is that the regulated entities are in the best position to know the hazards and risks associated with their specific operations, and are therefore in the best position to target means for reducing those risks. Managers are expected to develop plans, practices, or procedures to address both technological and human risk factors and then to keep track of compliance with those procedures, report on progress, and periodically reevaluate and improve risk management efforts. The job of the regulator in this case is to verify that the plans are sound and well justified, being consistently followed, and are regularly reviewed

___________________

67 “Federal Railroad Administration, Department of Transportation.” 49 C.F.R. Chapter II. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-49/subtitle-B/chapter-II (accessed May 3, 2024).

68 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2018. Designing Safety Regulations for High-Hazard Industries. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24907.

69 International Civil Aviation Organization. 2016. “Annex 19: Safety Management.” July.

70 “The International Safety Management (ISM) Code.” https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/humanelement/pages/ISMCode.aspx (accessed May 3, 2024).

71 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2018. Designing Safety Regulations for High-Hazard Industries. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24907.

by the operator for effectiveness. The regulator may also offer guidance on developing a high-quality SMS.

The RSIA mandates that each railroad establishes an RRP that “systematically evaluates railroad safety risks on its system and manages those risks in order to reduce the number and rates of railroad accidents, incidents, injuries, and fatalities.” The mandate is suggestive of congressional interest in railroads instituting SMSs. The committee observes, however, that when FRA required RRPs, it did so in a streamlined fashion that, as FRA acknowledged, does not mandate many elements that are typically part of an SMS.72 According to the rule, an RRP is acceptable if it simply concentrates on managing risks arising from changes involving (1) operating rules, (2) the implementation of new technology, and (3) reductions in crew staffing levels.

This limited set of RRP elements was criticized by safety management experts commenting on the RRP rule as it was being proposed by FRA.73 The commenters noted that an important element that was excluded from the rule was “processes and procedures for a railroad to manage changes that have a significant effect on railroad safety.”74 Accordingly, the rule does not require a railroad to preemptively address a major change in its operations in a deliberate manner by identifying the associated hazards, analyzing the potential risks arising from those hazards, and evaluating and explaining how the risks will be managed. FRA’s reasoning for streamlining RRPs in this manner is unclear given that the agency’s rule that governs SSPs for passenger railroads (also mandated in RSIA) does stipulate that SSPs should have processes and procedures to manage significant operational changes.75

The trend toward longer manifest trains would seem, by any measure, to represent a major operational change that could create or heighten train operational and handling challenges, such as managing in-train forces, ensuring proper train makeup, and maintaining crew communications. Accordingly, in a typical, fully developed SMS this change would be called out by assessing all potential hazards and risks and by describing the methods and means that will be used to eliminate or manage those risks. In this instance, an RRP patterned after an SMS would be expected to explain, among other things, the train makeup protocols that will be employed; the skills, readiness levels, and competencies required for crew members and how they will be met through means such as scheduling and training; and how technologies will be deployed (e.g., DP units, brakes, radio

___________________

72 Federal Register 85(32). February 18, 2020.

73 Ibid.

74 FRA. 2024. “Risk Reduction.” 49 C.F.R. Part 271, Subtitle B, Chapter II. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-49/subtitle-B/chapter-II/part-271.

75 49 C.F.R. Part 270.

systems, engineer-assist programs) and verified for effectiveness. In turn, if an SMS process was being followed, FRA would be expected to confirm, through critical reviews and audits, that each railroad’s risk reduction program does indeed cover such interests, is well reasoned and well justified, and is being followed faithfully and evaluated regularly by the railroad for effectiveness.

RSIA requires railroads to submit their RRP plans to FRA for approval, and in early 2022 FRA approved the plans of all the Class I railroads. To verify that railroads have followed the plans by implementing programs, FRA has been auditing railroad RRPs. The first program audited was for the Norfolk Southern Railway, completed in May 2024.76 While the auditors found that the railroad was generally in compliance with the RRP rule’s requirements, they identified a number of deficits.77 For example, the railroad did not demonstrate that it had followed the planned processes for identifying and analyzing hazards and mitigating associated risks. As a general matter, however, the audit’s focus was on verifying that the railroad’s program was in place and following the written plan and that all administrative requirements were being met. The audit did not include critical evaluations of the quality and thoroughness of the RRP risk evaluations, analyses, and promised mitigation actions.

Because RRPs are proprietary to individual railroads and do not require all elements of a traditional SMS, it is not possible for external parties, including this committee, to ascertain whether and how railroads are identifying and controlling the hazards and risks arising from their major operational changes, including their decisions to use longer manifest trains.

After issuing the RRP rule in 2020, FRA has conducted multiple training sessions for railroads and labor organizations representing many directly affected employees. During those training sessions, FRA explained the requirements of the rule, FRA’s expectations on the content of RRP plans, and the RRP approval process.78 To date, the training and guidance have not focused specifically on key elements of an SMS, such as how to conduct a high-quality, quantitative risk assessment or best practices for managing specific types of hazards and risks. It merits noting that Transport Canada first issued an SMS regulation in 2001. That regulation has since been updated periodically as the railroads and safety agency have gained more experience with these systems.

___________________

76 FRA. 2024. Audit Report, Norfolk Southern Railway (NS), Class I. FRA Audit No. 2024-NS271-10-1. May 15.

77 FRA. n.d. “NS Risk Reduction Program (Part 271) Audit Report.” https://railroads.dot.gov/elibrary/ns-risk-reduction-program-part-271-audit-report (accessed June 4, 2024).

78 Letter from FRA Administrator Amit Bose to Senator Chuck Schumer, reported in Railway Age, June 2023.

This page intentionally left blank.