Long Freight Trains: Ensuring Safe Operations, Mitigating Adverse Impacts (2024)

Chapter: 4 Long Trains and Crew Operations

4

Long Trains and Crew Operations

The challenges associated with operating long trains, as described in Chapters 2 and 3, have implications for how engineers and conductors are trained and their service readiness. In addition, the advent of long trains has coincided with reductions in the railroad labor force that are especially concentrated in trains crews and maintenance of equipment (MOE) personnel. This chapter outlines the impacts of long trains on labor and their training needs. The chapter begins with a brief overview of employment trends in the Class I railroads. The chapter then presents an extended discussion of impacts on train and engine employees, followed by a briefer examination of change to MOE employees. This chapter examines how training has or has not been adapted to the operational challenges of long trains. While engineer-assist systems make some engineer tasks easier, they do not replace the need for additional training inasmuch as engineer-assist systems are not always available. In addition, long trains may lead to increased crew fatigue. The chapter concludes with a comparison of training in the railroad industry with other industries.

RAILROAD EMPLOYMENT TRENDS GENERALLY

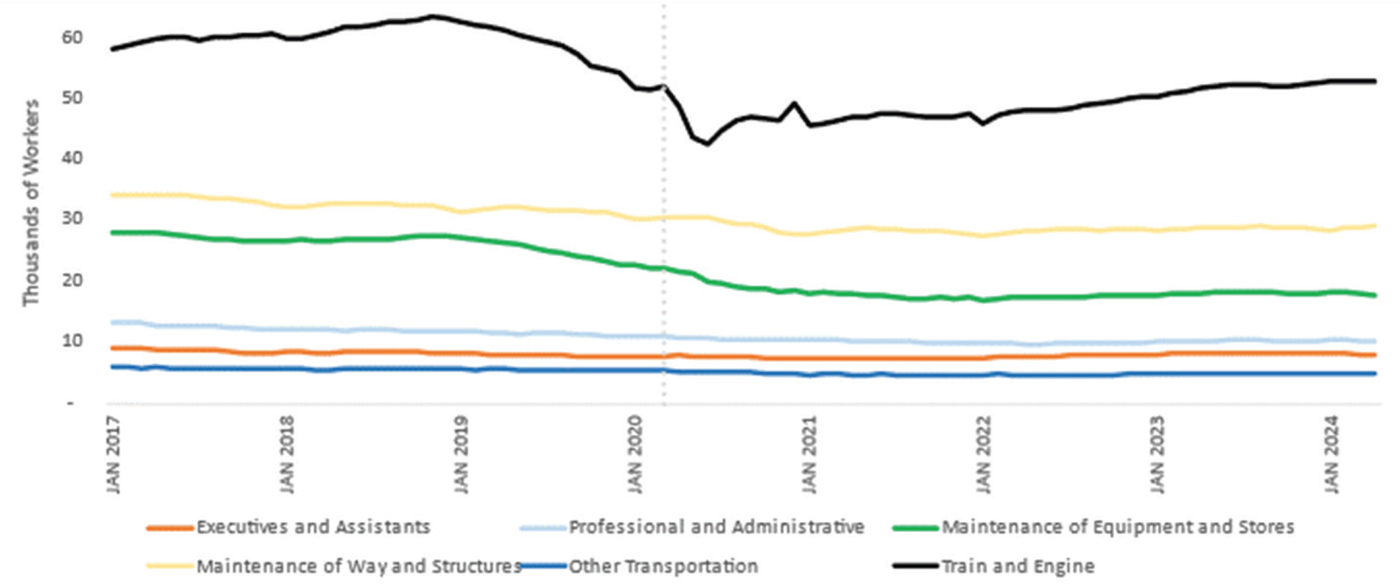

For a given tonnage of freight, running longer trains means running fewer trains. Therefore, long trains can reduce the need for labor. Federal data on employment in the Class I railroads (see Figure 4-1) show that train and engine employees and change to MOE employees have declined since 2015. The number of maintenance of way employees has seen a smaller decline, while the numbers of employees in other employment categories have

SOURCE: Surface Transportation Board. 2024. Quarterly Wage A and B data, https://www.stb.gov/reports-data/economic-date/quarterly-wage-ab-data.

remained relatively flat.1 This decrease in train and engine employees and MOE employees coincides with increasing train length, which as described in Chapter 2 dates to around 2017.

TRAIN AND ENGINE EMPLOYEES

Long trains are operated by an engineer and a conductor who share the responsibility for safe train operation. The engineer is responsible for operating the locomotive engine while the conductor supervises the operation and administration of the train and is responsible for the cargo and train equipment. This includes making sure that the cars and their systems are in good operating condition, and that train makeup is sound. The conductor and engineer are jointly responsible for the safe operation of the train in accordance with all rules and regulations.2 As described in Chapters 2 and 3, long trains can be more difficult to operate and add to the responsibilities of the engineer and the conductor.

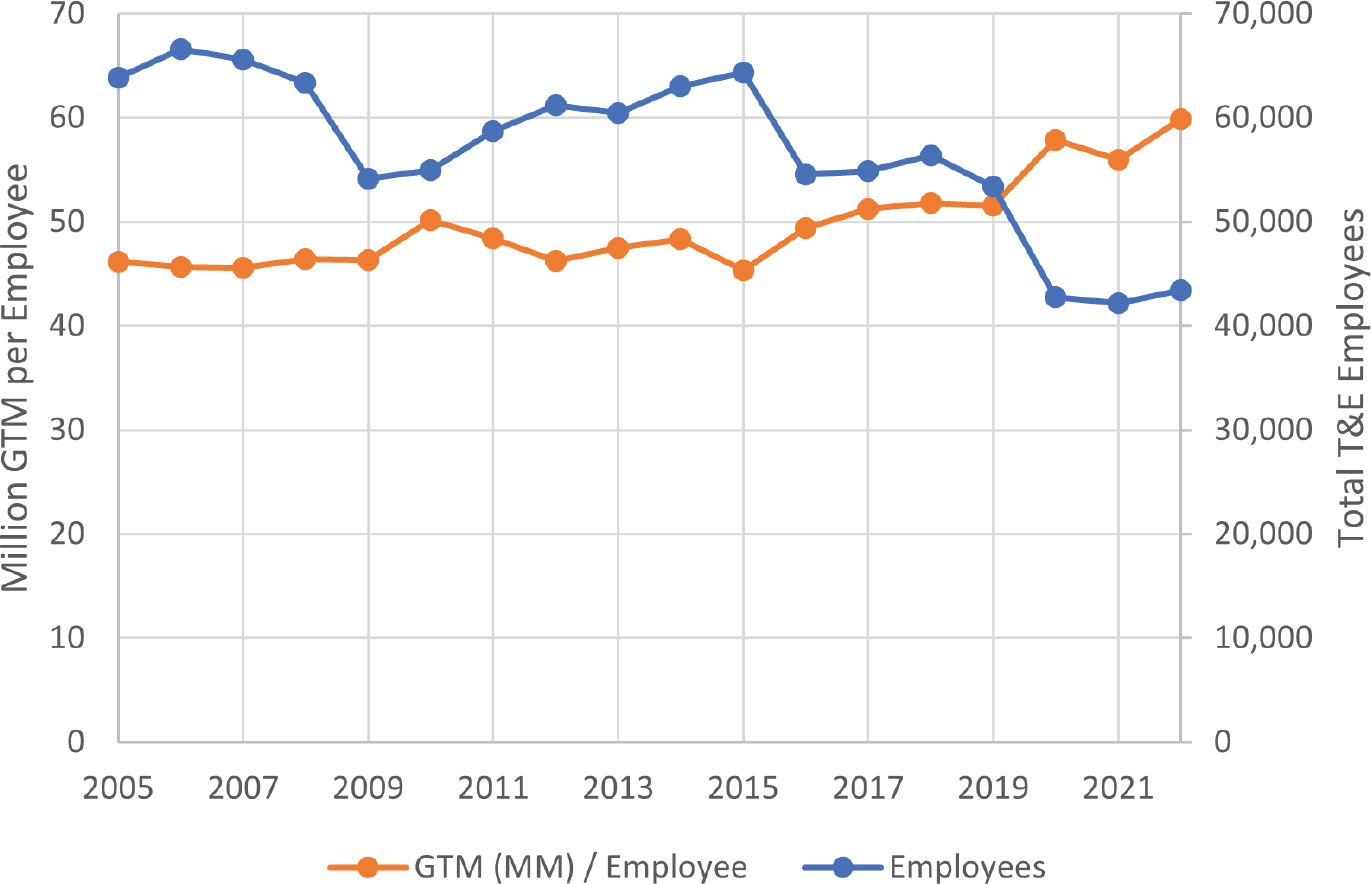

Figure 4-2 shows the recent decline in the number of train and engine employees accompanied by an increase in the gross ton-miles per employee for the four largest Class I railroads.3 Although the total number of train and engine (T&E) employees has fluctuated since 2005, gross ton-miles per T&E employee stayed relatively flat until it began an increasing trend in 2015. Between 2018 and 2022, total T&E employees decreased by 23%, while gross ton-miles per employee increased by 15%. Although T&E employees have reportedly not been working more miles per year, union leaders contend that longer trains increase the need to recrew trains before they reach their destination, resulting in a longer workday for T&E employees.4 This increased length of the workday comes from waiting for transport and traveling to their destination terminal, which are often in addition to their 12-hour maximum allowed work time.

Crew Preparedness and Training

As described in Chapters 2 and 3, long manifest trains, with their complicated makeup and multiple groups of DP locomotives, can create situations where controlling train speed while minimizing in-train forces is challenging even for a well-trained and experienced crew.

___________________

1 FRA (Federal Railroad Administration). 2024. “Labor and Employment.” Updated May 24. https://railroads.dot.gov/rail-network-development/labor-and-employment.

2 Sperandeo, A. 2023. “The People Who Work on Trains.” Trains, December 20. https://www.trains.com/trn/train-basics/abcs-of-railroading/the-people-who-work-on-trains.

3 STB R-1 data and STB Wage A and B reports.

4 SMART, BLE-T, and ATDA union presentations to committee, January 2023.

SOURCE: STB R-1 data and STB Wage A and B reports.

Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) regulations require railroads to train and certify their train crews.5 Qualified locomotive engineers must demonstrate proficiency in operating trains in the most demanding type of service they are permitted to perform, which includes operating longer trains with or without DP locomotives.6 There is an initial period of classroom training; however, the bulk of most training programs for new employees takes place in the field during normal operations. For the most part, this training for locomotive engineers and conductors is done via mentoring, with an experienced engineer riding with a new student and conductor trainees working under the direct supervision of a more experienced conductor. Locomotive engineers and conductors are required to

___________________

5 “Chapter II—Federal Railroad Administration, Department of Transportation.” 49 C.F.R. Parts 240, 242, and 243. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-49/subtitle-B/chapter-II (accessed May 6, 2024).

6 49 C.F.R. § 240.213. FRA regulations require that each railroad shall determine that the person has the knowledge and skills to safely operate a locomotive or train in the most demanding class or type of service that the person will be permitted to perform. Specific topics for training programs include personal safety, railroad operating rules, handling trains over the railroad’s territory, federal regulations, and operating the different train types normally used by the railroad.

be recertified for train service once every 3 years, with annual training in between.7 Railroads are required to conduct annual performance evaluations of engineers to ensure that they can safely operate trains according to federal railroad safety requirements.8

Unusual and/or emergency situations cannot be specifically addressed during the training that takes place in the field during normal operations. To prepare for such situations, representatives of Class I railroads stated that they train their crews on trains and simulators that cover various routes, scenarios, and train lengths.9 Each railroad develops its own program of initial and recurrent training for its train crew members. Although these programs are similar for each railroad, they are not identical. While one Class I railroad does require annual engineer simulator testing for trains up to 12,000 ft in length, several others operating in the United States indicated that they had not changed anything in their respective training curricula to specifically address the operation of long trains.10 Instead, they stated that train length was not an important factor in a crew member’s ability to successfully complete their job requirements and that there were no issues that would require any modifications to the training that employees receive.11

However, representatives of railroad workers did not concur with the railroads’ position on the need for additional or modified training.12 Union representatives expressed concern that some railroads do not provide sufficient training for crews to operate longer trains, resulting in locomotive engineers and conductors that lack the necessary training and experience to handle longer trains.13

Derailments Caused by Improper Train Handling

Chapter 2 provided evidence that train derailments with makeup and handling issues have increased coincident with the increasing length of manifest trains. As an example of this problem, an FRA accident report on a 2023 derailment concluded that handling was a primary cause,

___________________

7 At some railroads this is done utilizing simulator technology, and at some railroads it is done in the field with a check ride performed during a regular train operation.

8 3549 C.F.R. § 240.129. In addition, FRA regulations require that FRA review new and materially modified railroad-crew-training programs and also meet with railroads to discuss strategies to reduce instances of poor safety conduct by train crews. See 49 C.F.R. § 240.103 and 49 C.F.R. § 240.309, respectively. According to FRA, the agency may audit training programs and require railroads to update deficient training programs to comply with regulations.

9 FRA. 2024. “Stakeholder Perceptions of Longer Trains.” February 16. https://railroads.dot.gov/elibrary/stakeholder-perceptions-longer-trains.

10 Class I presentation to committee, March 2023.

11 Class I railroads presentation to committee, April 2023.

12 SMART presentation to committee, January 2023.

13 SMART, BLE-T, and ATDA union presentations to committee, January 2023.

noting the engineer’s improper use of dynamic brakes.14 In the report, FRA stated that the engineer’s last annual check ride did not test the engineer’s ability to handle a train of the size of the derailed train. The train that derailed consisted of 15,519 tons and 11,374 ft, with both a mid and a rear DP consist. The report stated:

Analysis-Certification Process: During the investigation the FRA reviewed the engineers operational performance exam (annual ride) and the engineers skills performance exam (certification ride) which revealed the following: Federal Regulation listed under 49 CFR 240.127(b) requires the evaluation to consist of “being evaluated for qualification as a locomotive engineer in either train or locomotive service to determine whether the person has the skills to safely operate locomotives and/or trains, including the proper application of the railroad’s rules and practices for the safe operation of locomotives or trains, in the most demanding class or type of service that the person will be permitted to perform.” However, the train used for the engineer’s certification ride composed of a simulated 55 car intermodal train with only 4,086 tons and 5,462 feet (including locomotives).

FRA concluded that the smaller train used in the simulation was not equivalent to the regulation’s requirement that training be on the most demanding class of service for the subdivision.

Increasing Reliance on Control Technology

Class II railroads are also increasingly relying on technology to guide crew members, especially locomotive engineers, on the operation of trains over their assigned territory. As described in Chapter 3, engineer-assist systems direct both power and braking decision making for trains.15 Not only are train crew members increasingly tasked with relying on these systems, but also, they are often required to comply with the system’s recommended control inputs. One reason for the reliance on engineer-assist systems is the difficulty in separately controlling all locomotives in a train (mid-train distributed power [DP] locomotives and end-of-train DP locomotives) to minimize in-train forces has increased greatly as trains extend over multiple uphill and downhill grades simultaneously.

However, one notable limitation of the engineer-assist technologies that are currently being used is that these systems primarily use dynamic

___________________

14 BNSF derailment near Williams, Arizona, on June 8, 2023, FRA file No. HQ-2023-1863. The cause of the derailment was “[H503] Buffing or slack action excessive resulting from improper use of dynamic brakes.”

15 Wabtec and LEADER presentations to committee, May 2023.

braking for controlling the speed of the train.16 As covered in Chapter 3, overreliance on dynamic brakes can be problematic in trains that are not properly marshalled. According to one railroad, their engineers were trained to not use air brakes unless the engineer-assist system recommends doing so.17 Another railroad discourages their engineers from using air brakes, but they had the prerogative to do so if they concluded that it was necessary to safely control their train.18 It should be noted that there are some mountain grades in the country where the use of both air brakes and dynamic brakes is required because dynamic brakes alone are not adequate to control the train on very steep grades and/or while moving at slow speeds.19

The problem with the increasing dependence on engineer-assist systems, especially as trains have grown longer, is that they are not yet reliable enough to work all the time in all situations.20 As such, they are not a substitute for effective training and their use does not negate the need for training as required by FRA.

Given that running trains with less horsepower per gross ton-mile is proven to reduce fuel burn,21 the 22% increase appears to come more from reduced horsepower per gross ton. Another railroad presented a study comparing winter operations using shorter trains to operations over the rest of the year using longer trains. The study showed fuel savings for running longer trains.22 The study attributed all the increase in fuel consumption during the winter to running shorter trains; however, it did not account for the impact that cold weather operations could have on fuel burn.

Research on Train Size and Fuel Economy

Railroads have made changes to operations that can and have resulted in decreased fuel use over recent decades. Engines have become more efficient and therefore more cost-effective.23 Rail cars are built to carry heavier loads, reducing the number of cars needed to move the same amount of tonnage. Wayside detectors have reduced flat spots on wheels and therefore rolling resistance.24 Reducing train speeds to below 40 mph also saves

___________________

16 Ibid.

17 UP and CSX presentations to committee, March 2023.

18 Ibid.

19 Transportation Safety Board of Canada. 2022. “Locomotive and Freight Car Brakes.” March 31. https://www.tsb.gc.ca/eng/medias-media/fiches-facts/r19c0015/r19c0015-20220331-3.html, p. 209.

20 BLE&T presentation to the committee, January 2023.

21 Cetinich, J. 1975. Fuel Efficiency Improvement in Rail Freight Transportation: United States. FRA.

22 CN presentation to committee, April 2023.

23 Lustig, D. 2010. “AC vs. DC: What’s the Difference?” Trains 70(5):18–19.

24 Ernest Robl, E. 2006. “Smarter Detectors, Less Talking.” Trains.

fuel.25 As described in Chapter 3, the Class I railroads introduced a greater reliance on dynamic brakes, and the subsequent adoption of engineer-assist systems to speed the adoption of dynamic brakes, in part to increase fuel efficiency.26 All railroads have implemented or are implementing anti-idling policies to provide additional fuel savings and therefore reduce emissions.27

On the other hand, long trains have led to fewer locomotives in service. Running trains with less horsepower per gross ton, which reduces the ratio of horsepower to gross train weight, while maintaining maximum speed levels produces the greatest savings relative to increases in minimum over-the-road train running times.28 In addition, having fewer locomotives in service will reduce idling, further increasing overall fuel economy.

Therefore, although railroads have clearly reduced fuel usage since the advent of long manifest trains, it is not clear that such savings are from running longer trains as opposed to other locomotive operating policies. In addition, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions can be reduced through other means. Several railroads are increasing their utilization rates of low-carbon fuels and testing hydrogen-powered locomotives to provide even cleaner locomotive operations.29

Train Crew Fatigue and Long Trains

Train crew fatigue may increase as train length increases.30 For example, according to union representatives, if a train stops unexpectedly because of a mechanical or other issue, a train crew member must typically walk the length of the train. For a 2-mile train, walking from the lead locomotive to the end and back would require walking 4 miles, a journey made substantially more difficult during inclement weather or at night. Additionally, a recent FRA safety advisory requires that any unattended train must have a sufficient number of hand brakes applied to prevent unintended

___________________

25 Hopkins, J.B. 1975. Railroads and the Environment: Estimation of Fuel Consumption in Rail Transportation: Volume 1. Analytical Model. Federal Railroad Administration.

26 See Trip Optimizer and LEADER section in Chapter 3.

27 AAR presentation to committee, March 16, 2023.

28 Efficiency can be further optimized by shutting down locomotives in a consist when they are not needed to power the train, especially if idling specific locomotives permits the remaining locomotives to operate at full throttle. For more information, see Cetinich, J. 1975. Fuel Efficiency Improvement in Rail Freight Transportation. Federal Railroad Administration.

29 “Freight Shipping and Its Impact on Climate Change.” February 7, 2024. http://www.up.com/up/customers/track-record/tr021522-impact-of-freight-shipping-on-climate-change.htm.

30 FRA. 2024. “Stakeholder Perceptions of Longer Trains.” February 16. https://railroads.dot.gov/elibrary/stakeholder-perceptions-longer-trains.

movement.31 As train length has grown, both the number of hand brakes required to secure a train and the distance that conductors must walk to set the hand brakes has increased significantly. According to union representatives, such physically demanding tasks can increase crew fatigue.32 Labor reported that crews often have long days due to not getting to destinations before they run out of time on the hours of service and have to wait for replacement crews before resting.33

EQUIPMENT MAINTENANCE EMPLOYEES

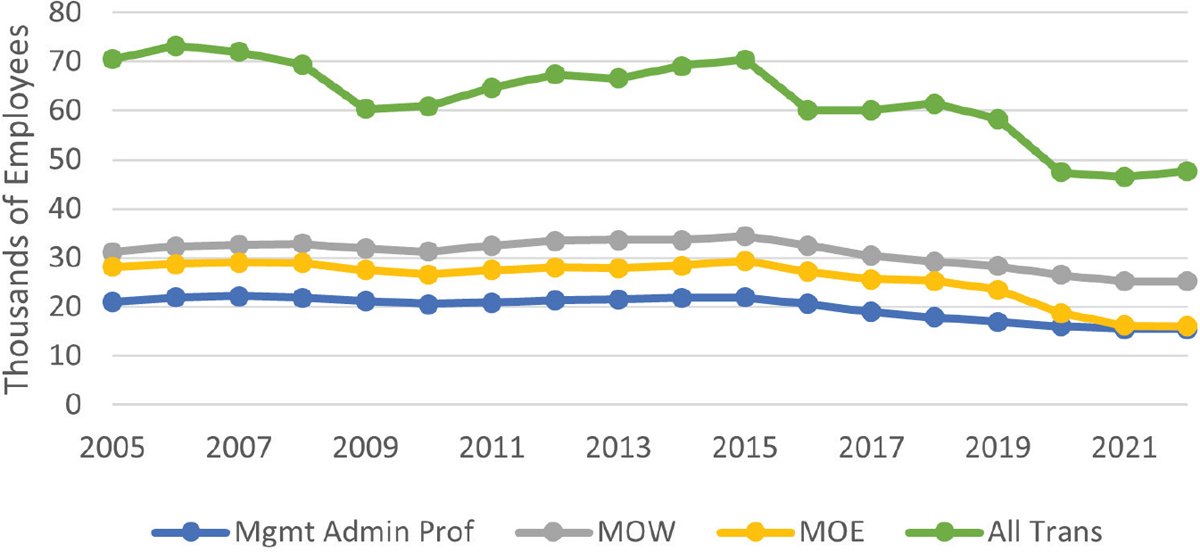

The long-term drop in railway employment has been seen in every employee category (as shown in Figure 4-1), but the percentage decline is highest for MOE, which has experienced declines of approximately 43% from 2015 to 2023.34 This reduction of MOE personnel has coincided with increased train length, requiring that more cars be managed, inspected, and maintained per train. Some of the reasons for MOE workforce reductions include (1) increasing reliance on sophisticated sensor suites and artificial intelligence to find mechanical problems quickly and without human inspection, (2) reduced number of yards and therefore places to inspect trains, (3) increased use of modern locomotives, (4) increased use of subcontractors for a variety of tasks, and (5) greater locomotive productivity.

Locomotive Maintenance

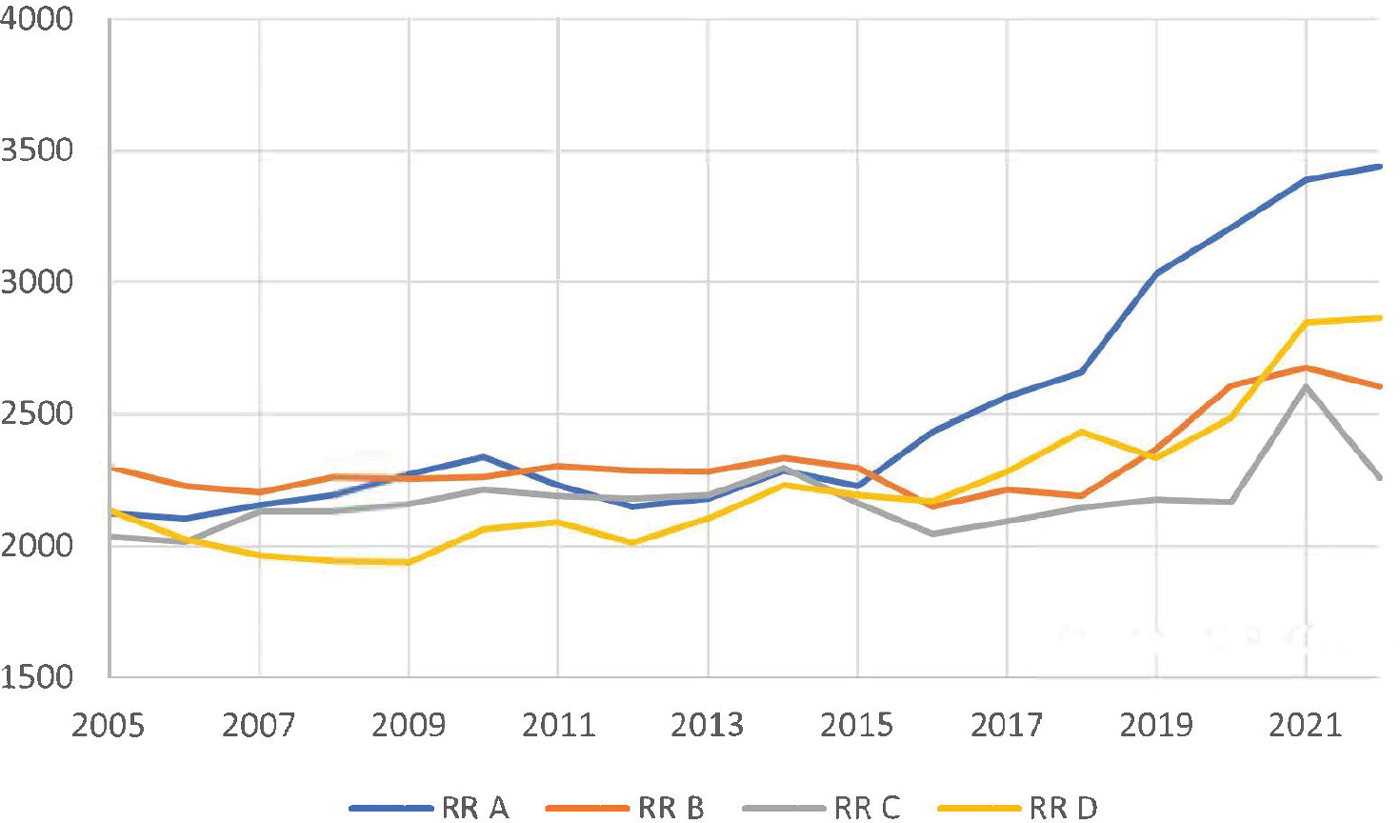

Increased locomotive productivity is measured here as gross ton-miles per locomotive mile, which has increased greatly from 2015 to 2022 (see Figures 4-3 and 4-4). It is not known whether this improved productivity comes from increasing reliance on modern locomotives or from using fewer locomotives per gross ton-mile.35 However, improved locomotive productivity results in needing fewer locomotives, which reduces the number of locomotives maintained and, therefore, the need for MOE personnel.

___________________

31 FRA. 2022. “Safety Advisory 2022-02; Addressing Unintended Train Brake Release.” Federal Register 87:80256. December 29. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/12/29/2022-28336/safety-advisory-2022-02-addressing-unintended-train-brake-release.

32 SMART and BLE-T presentations to committee, January 2023.

33 Ibid.

34 STB Quarterly Wage A and B data, https://www.stb.gov/reports-data/economic-data/quarterly-wage-ab-data.

35 In addition to being more powerful and having better traction control, modern locomotives are more reliable. They use alternating current traction motors, which do not overheat when used at maximum power. Older direct current traction motors would overheat when used at maximum power for too long. For more information, see Lustig, D. 2010. “AC vs. DC: What’s the Difference?” Trains 70:18–19. Milwaukee, WI: Kalmbach Publishing Company.

SOURCE: STB Wage A and B reports.

SOURCE: STB R-1 data.

Equipment Inspection

Longer trains require that more cars be managed, inspected, and maintained per train. This has occurred at the same time that carmen have raised concerns36 about increasing pressure to inspect and release trains quickly, which has also been reported in recent investigative journalism.37 The time needed to inspect a single car is independent of train length. Because there are more cars in a long train, the total inspection time for the entire train—and therefore each car in that train—is also longer. However, railroad presentations confirm there has been an increase in the use of technology to perform car inspections across railroad networks. For example, acoustic bearing detectors are the “first line of defense,” followed by hot bearing and axle detectors, wheel impact load detectors, portal detectors, high and wide load detectors, and dragging equipment detectors.38

Implementing such technology systems and the use of inbound inspections performed on arrival of the car at the terminal has advantages in getting defective cars set aside for repair. In summary, while wayside detectors have reduced the need for car inspections in yards, long trains still require more time for inspection when arriving at and departing manifest train yards.

___________________

36 BLE-T and SMART presentations to committee, January 2023.

37 Fung, E., K. Maher, and P. Berger. 2023. “‘Hurry Up and Get It Done’: Norfolk Southern Set Railcar Safety Checks at One Minute.” The Wall Street Journal; Sanders, T., J. Lussenhop, D. Morton, and G. Sandoval. 2023. “Do Your Job: How the Railroad Industry Intimidates Employees into Putting Speed Before Safety.” Probublica; Sanders, T., D. Schwartz, and J. Sterman. 2023. “As Rail Profits Soar, Blocked Crossings Force Kids to Crawl Under Trains to Get to School.” Propublica.

38 CN presentation to committee, April 2023.

This page intentionally left blank.