Transforming Undergraduate STEM Education: Supporting Equitable and Effective Teaching (2025)

Chapter: 5 Using the Principles to Improve Learning Experiences

5

Using the Principles to Improve Learning Experiences

This chapter provides some examples of ways that instructors can put the concepts of the Principles for Effective and Equitable Teaching (described in Chapter 4) into practice. An instructor beginning their journey to becoming a more equitable and effective teacher might initially choose to focus on just one Principle at a time or pick one of the example strategies described below as an entry point. Another might apply multiple Principles in an interconnected way to build upon strategies they have previously incorporated into their teaching. Designing and implementing equitable and effective learning experiences is not a matter of checking off each of the Principles from a list; it is an ongoing process requiring repeated reflection and innovation. This reflection involves getting to know both yourself and your students, including questioning your assumptions about your own expectations and approaches. In order for instructors to teach equitably and effectively, they need to consider the students’ point of view and reflect on the planned approach and its implications for equity and student learning in all aspects of course preparation. Engaging in professional learning and development (discussed in Chapter 8) to support course design can be an effective way of learning to create these environments.

The Principles can be a lens for looking at many different aspects of a course, including the content covered, instructional practices, students’ tasks, group work, and grading. While the priorities and expectations of disciplinary units and institutions can sometimes be a barrier to transforming teaching, individual faculty who are interested in re-imagining their teaching based on the Principles can consider small changes as starting points. For example, faculty can start by including a few activities for students that

reflect the Principles, testing out new approaches to assessment, expanding opportunities for students to get to know each other, or revising the syllabus to provide more transparency.

The chapter is organized into two main sections that reflect major themes captured by the Principles: designing for learning, and cultivating an equitable and effective learning environment. Both sections discuss strategies, approaches, and tools that instructors, either individually or collaboratively, might consider as they reflect on course design and instruction. The section on creating an environment compatible with productive learning explores the need for instructors to reflect on their own assumptions about learning and teaching as well as the need for instructors to get to know their students in order to make design choices that support learning for those students. Implications for disciplinary units and institutions are discussed in subsequent chapters. In this and subsequent chapters we often refer back to the Principles presented in Chapter 4 to illustrate how they are relevant to the topics of later chapters. To avoid repeating the long names of each Principle, we utilize the same shorthand as listed in Table 4-1.

DESIGNING FOR LEARNING

A foundational concept of the Principles for Equitable and Effective Teaching presented in Chapter 4 is that students’ learning is the primary goal of teaching. Focusing on student learning as the goal of a course has several important components for the instructor, including clearly articulating what they expect students will know and be able to do by the end of a course; making use of assessments that allow them to see students’ progress toward those goals; and making use of class time to help students build their skills and be successful on the assessments, thus achieving the learning goals. Designing courses explicitly with learning goals in mind may require a shift in the instructional approaches and classroom activities that instructors use.

Learning is understood by researchers to be an active process that involves both development of an understanding of key concepts in a discipline and the ability to use that knowledge to engage in disciplinary practices (the research basis for this is discussed in greater length in Chapters 3 and 4 and is reflected in the Principles). This means that more traditional instructional approaches that emphasize memorizing decontextualized facts or undertaking decontextualized procedures are not as effective as learning experiences that provide students with opportunities to reflect on and use their developing knowledge (see Chapter 3 for additional discussion of the supporting research). Instructors therefore need to reflect on their own assumptions about teaching and learning as they design courses. In this section, we present guidance and strategies for designing around learning goals.

Applying the Principles has implications for classroom instruction. Table 5-1 presents some of the changes that could increase student learning over “traditional” approaches. The column on the left describes strategies that help to center and support students’ learning. The column on the right describes strategies that are common in more “traditional” STEM learning and are less effective for supporting students’ learning. Moving away from strategies in the second column to strategies in the first column will help an instructor’s teaching become more equitable and effective and have a positive impact on student learning. As discussed in Chapter 3, these strategies reflect multiple lines of research on learning and teaching that have solidified over the past 30–40 years. The following sections elaborate on the approaches in the left column.

The Universal Design for Learning Framework

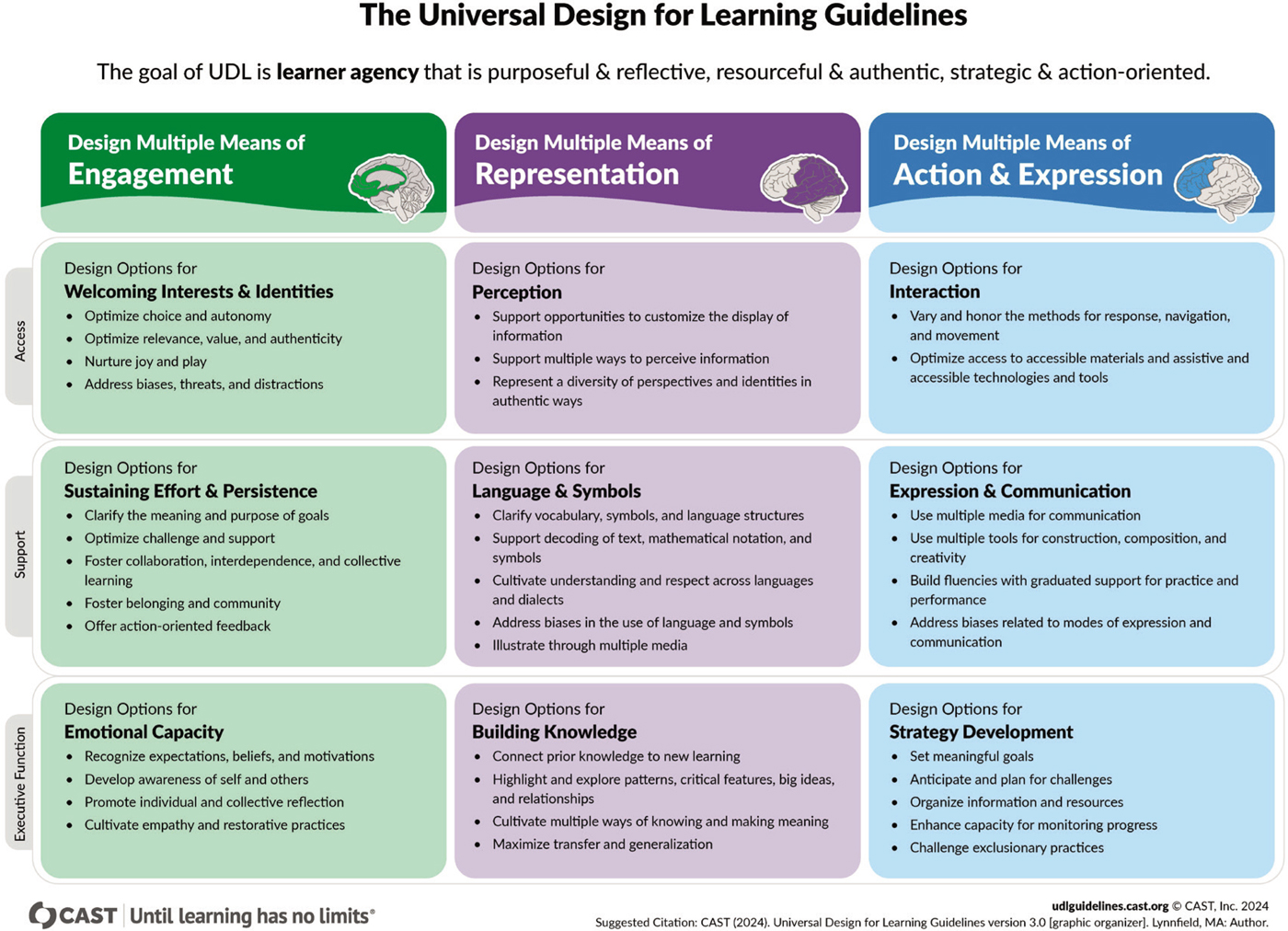

One tool that can be helpful for developing teaching practices that center student learning is the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework, which is grounded in principles of neuroscience and can be utilized to promote equitable learning in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM; CAST, n.d.). UDL guidelines focus on three major areas, including the design for multiple means of (a) engagement, (b) representation, and (c) action and expression. This framework was developed to account for variability in how people learn, including people with disabilities.

TABLE 5-1 Changes That Can Increase Teaching Strategies Focused on Student Learning

| Teaching Focused on Student Learning Includes | |

|---|---|

| More of… | Less of… |

| Clear articulation of learning goals and how the work done in the course will help students achieve learning goals | A focus on getting through a set amount of content |

| Course structures that engage students as active learners | Course structures that maintain students as passive receivers of information |

| Activities that regularly engage students in using the skills and knowledge of the discipline | Separate laboratory sections focused on skills without clear connections to course content |

| Being transparent about opportunities and expectations for learning and engagement | Assuming that all students are aware of what they “should” be doing |

| Grading practices that allow for formative feedback and focus on mastery | Grading practices that focus on a theoretical distribution (a curve) and promote competition in a few high-stakes assessments |

CAST updated the UDL guidelines in July 2024 to include components addressing systemic bias and exclusion in learning environments, making the framework even more comprehensive. Figure 5-1 shows the latest version of the UDL guidelines (CAST, 2024). A paper commissioned for the 2023 National Academies event on Disrupting Ableism and Supporting People With Disabilities in the STEM Workforce explored the intersection of UDL with STEM learning in higher education and provides some guidance for making classroom, laboratory, field, and digital spaces inclusive and accessible.1

For STEM instructors seeking to implement UDL in their courses, one useful approach is called plus-one, whereby they consider more than one way to represent course concepts, engage students in their learning, and have students demonstrate their learning (Behling & Tobin, 2018). As an example, illustrating a concept in more than one way in a STEM course might involve any of the following: physical or digital models, animations, problem-solving, a case study, descriptive, or oral text. Additional ideas for making courses more accessible are often available from campus centers for teaching and learning or campus disability resource centers as well as national centers such as the DO-IT center at the University of Washington.2

UDL has the potential to be integrated to scale within STEM courses to facilitate equitable learning experiences for students with and without disabilities, and to disrupt conceptions of normalcy and traditional approaches to teaching that do not account for learner variability (Fornauf & Erickson, 2020; Schreffler et al., 2019). In a systematic review of 17 articles involving UDL integration in higher education, 15 reported positive outcomes, one had mixed findings, and one did not report outcomes (Seok et al., 2018). Such results highlight the promise of utilizing UDL to support equitable and effective teaching.

Designing Around Clear Learning Goals

When designing for learning, a critical step is to develop clear learning goals for students. These goals then guide selection of course materials, development of tasks and activities for students, and assessments of student learning—an intentional approach to course design that reflects Principle 7: Intentionality and transparency. Starting with course goals allows instructors to make good decisions about what to include and exclude from their course by asking, “Will this help my students achieve these learning goals?”

___________________

1 The full version of the paper is available at https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/27245/Johnston_and_Perez_Creating_Disability-Friendly_and_Inclusive_Accessible_Spaces_in_Higher_Education.pdf

2 More information about the University of Washington’s DO-IT center is available at https://www.washington.edu/doit/

SOURCE: CAST (n.d.), retrieved from https://udlguidelines.cast.org

Articulating learning goals for students and designing toward them can be done for an entire course, a sequence of courses, or for a single class session. In some academic units, instructors may have less flexibility in articulating learning goals and redesigning a course accordingly because the course content is laid out by the unit. However, it can still be useful to think through the learning goals related to the established content, or even the goals for a particular class period.

Backward design is one common framework for developing courses based on explicit learning goals (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). In backward design, the first step is to define course-level learning goals that are substantial, measurable, and achievable (or plausible, in the case of goals in the affective domain). The second step is to develop assessments to determine the extent to which students have met the learning goals. The final step is to design activities that help students develop the knowledge and skills they need to succeed on the assessments. By foregrounding learning goals, and building content and assessments around them, backward design allows instructors to be more intentional and transparent in their teaching (Neiles & Arnett, 2021; Reynolds & Kearns, 2017). This approach differs from approaches to course design that focus mainly on identification of the disciplinary content that needs to be “covered” in a given course. A focus on coverage without articulating goals for what students should learn about the discipline and how they can demonstrate their competence can lead to adoption of less effective instructional approaches, such as heavy reliance on lecture and memorization.

There are tools available to help instructors implement backward design. Neiles and Arnett (2021) provide a primer on using backward design for chemistry laboratory courses to facilitate a more inclusive, scaffolded, and intentional curriculum. Reynolds and Kearns (2017) developed a planning tool that incorporates backward design, active learning, and assessment.

In some STEM disciplines, learning goals have been defined by the community or by outside accrediting bodies, and these can be used as a starting place for designing a course. For example, Vision and Change in Undergraduate Biology Education (American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2009) articulates disciplinary core content and competencies that have been translated into program- and course-level learning outcomes at many institutions (Brownell et al., 2014; Clemmons et al., 2020). The BioSkills Guide is one example that provides a set of measurable learning outcomes for use in the design of individual courses and activities (Clemmons et al., 2020). In the geosciences, the community came together during the COVID-19 pandemic to define learning outcomes for capstone field experiences so that alternatives to in-person field courses could be

designed that would meet the needs of students (Burmeister et al., 2020; Rademacher et al., 2021).

Clearly articulated learning goals can help with the careful selection and effective use of instructional resources in the classroom. Instructors may think about a textbook as the primary resource for their course and may choose a textbook based on content and familiarity. However, when choosing textbooks, instructors often need to consider factors such as cost, availability, accessibility, supporting materials for students, and equity and access issues (Marsh et al., 2022). While textbooks from traditional publishers can be unaffordable for low-income students, there are alternatives to each student purchasing a new textbook (older editions, used books, book rentals, library copies, etc.); another alternative is the growing availability of online “open” textbooks, which can be accessed for free, though these may not be available for specific content areas or more advanced courses (Bliss et al., 2013; Cozart et al., 2021; Hilton, 2016; Martin et al., 2017a). It can be useful to choose open educational resource (OER) versions of tools, but they must be properly evaluated first. OER tools might include open-source software and other informal learning materials in the public domain (Diaz Eaton et al., 2022).

Textbooks are not the only instructional resources to consider; digital tools can also support student learning. High-quality instructional resources of other formats (e.g., video recordings, visualizations, simulations) can also support students’ active engagement in disciplinary learning (see the next section for further discussion of active engagement which is related to Principle 1: Active engagement).

Many publishers offer access to digital learning tools, collectively called “courseware,” that are designed to be adaptive platforms that allow students to demonstrate their understanding and allow instructors to monitor their progress. These often contain multimedia lessons, practice problems, and formative assessments and are most commonly available at the introductory level (e.g., Neisler & Means, 2021). While courseware can be expensive, there are ways that institutions can fund access to avoid passing on the cost to students, which may have equity implications. The degree to which courseware aligns with course organization and structure (such as a student-centered adaptive approach) impacts the student experience (O’Sullivan et al., 2020).

Disciplinary and professional societies that focus on teaching sometimes produce curricular materials (e.g. American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2009; Behbahanian et al., 2018; Steer et al., 2019), as do grant-funded efforts (Branchaw et al., 2020; Gosselin et al., 2019; Harlow et al., 2020). Unlike textbooks and courseware produced by publishers,

these resources are often free to use due to requirements from their funding sources. They are often based in the research on how people learn (e.g., Steer et al., 2019) and often have been tested in college classrooms for their effectiveness.

Engaging Students Actively

Courses can be designed to develop skills within a particular discipline through the use of inclusive teaching strategies and active learning approaches centered around group work and peer instruction; this incorporation of active learning into STEM courses is the focus of Principle 1: Active engagement. To truly develop skills in a discipline, the activities within a course must not only provide active engagement in learning, but must also be aligned with course goals and desired disciplinary outcomes.

As discussed in Chapters 1 and 3, historically, STEM teaching has been didactic and instructor centered, largely featuring in-person lectures; this has shifted some in recent years, but didactic instruction remains the dominant way that STEM is taught (Stains et al., 2018). Research evidence makes clear that this traditional approach is ineffective and even alienating to many students and that active learning approaches are better suited to developing robust conceptual understanding, facilitating transfer of learning across contexts, and promoting long-term retention of ideas (Armbruster et al., 2009; Devlin & Samarawickrema, 2010; Ebert-May et al., 1997; Hogan & Sathy, 2022; Lyle et al., 2020). Evidence suggests that active learning tasks give students an opportunity to construct their own knowledge and understanding, requiring them to do more than simply passively listening to lectures (Freeman et al., 2014).

When implementing active learning approaches, the instructor acts as a guide, facilitator, and expert in the discipline, but is not the focus of the class. Instead, students’ tasks and student learning are the focal point. There are many ways to design and implement courses that incorporate active learning, and many strategies have been shown to lead to improved course outcomes for all students. Instructors can learn from the developed approaches or begin on a smaller scale by incorporating a few active learning tasks or group work into a course (Balta et al., 2017; Mazur & Watkins, 2010; Ruder et al., 2020). See Box 5-1 for some established approaches for actively engaging students.

There are many ways that instructors can actively engage students in their learning. One approach is to have students do preparatory work outside of class and then have them participate in deliberate practice facilitated with active learning and groupwork during class. Intentional preparatory

BOX 5-1

Approaches and Resources for Actively Engaging STEM Students in Learning

Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning (POGIL)a is a teaching approach that focuses on students developing understanding of both disciplinary content and process skills such as critical thinking and problem solving. Students frequently examine a carefully chosen or crafted model (e.g., figure, data) and use it to consider guiding questions provided by the instructor. These models anchor cycles of exploration, concept invention, and application as students work to make sense of the model and integrate it with their existing knowledge. This work is often done in teams with assigned roles (e.g., recorder, presenter, reflector). The instructor guides the students to explore new concepts that are central to the learning goals of the course and the development of disciplinary knowledge. (Balta et al., 2017; Mazur & Watkins, 2010; Ruder et al., 2020; Chapter 5 by Asala in Keith-Le & Morgan, 2020).

Just in Time Teachingb is a two-step learning process in which students do an assignment before class that the instructor evaluates in order to determine how to spend class time. The just in time feedback right before class meets allows the instructor to modify the lesson so that it provides information on the topics students most need help to understand instead of preselected content. The idea is that classes become more student centered and that students are encouraged to take responsibility for learning outside of class (Novak et al., 1999).

Peer Instructionc is a technique in which conceptual questions are intermixed with instructor-led lecture. The conceptual questions are designed to help student understanding and to address misconceptions. Polling is used as students vote using a flash card or a clicker. The instructor checks to see how many students answer correctly and guides another activity in which students try to convince their neighbors that they have the right answer. Following peer discussion, students are asked to do another poll. The lesson ends with the instructor explaining detailed information about the correct answer (Crouch & Mazur, 2001; Gong et al., 2023; Mazur, 1997).

__________________

aMore information about POGIL is available at https://pogil.org/

bMore information about Just in Time Teaching is available at https://www.vanderbilt.edu/advanced-institute/#:~:text=Just%2Din%2DTime%20Teaching%20

cMore information about peer instruction is available at https://mazur.harvard.edu/researchareas/peer-instruction

work can include pre-reading (Freeman et al., 2007) or preparatory videos (Casper et al., 2019), and low-stakes knowledge tests. In-class deliberate practice with deliberate group work and individual accountability, can be implemented with peer instruction (Crouch & Mazur, 2001; Smith et al., 2009) and audience response devices such as clickers (Kay & LeSage, 2009). Practice exams provided throughout the term are equally effective and can be graded by peers or by students themselves (Jackson et al., 2018). This approach has been adopted in large, gateway STEM courses with positive outcomes for students (Eddy & Hogan, 2014; Haak et al., 2011; Theobald et al., 2020). Such courses improve student learning (Freeman et al., 2007) and have a disproportionate benefit to students from minoritized groups (Eddy & Hogan, 2014; Haak et al., 2011).

When designing tasks and activities for students it is important to consider which students may or may not benefit from the choices that are made. For active learning to be successful, equitable, and effective it is important that the instructor carefully constructs inclusive assignments, works to create an environment that is welcoming and inclusive, and embraces mistakes as part of the learning process (Dewsbury, 2020; White et al., 2020). Some approaches to active learning and group work can cause increased challenges for women; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual/aromantic/agender, plus other related identities; students with anxiety and/or depression; neurodiverse learners; students with disabilities; and other underserved students (Araghi et al., 2023; Cooper & Brownell, 2016; Cooper et al., 2018; Downing et al., 2020; Gin et al., 2020).

Designing Group Work and Opportunities for Collaboration and Cooperation

Group work and opportunities for collaboration are an integral part of active learning. They also reflect Principle 3: Affective and social dimensions. Intentionally designing interactive activities and assignments can provide students with opportunities to learn from each other as they solve problems, conduct investigations, and reflect on material presented in lecture or texts. Social interactions can also have a positive effect on motivation when activities foster positive interdependence, and students are able to support the work of others and contribute to a larger effort (Brame & Biel, 2015). These activities can be short components integrated into a lecture format or can serve as the predominant form of instruction. This kind of positive interdependence can also occur across venues, such as courses, living learning residences, workplaces, and in the community.

Group work can take many forms (reviewed in Johnson et al., 1998). For example, groups can be informal or formal (e.g., groups where students turn to their neighbor to discuss vs. are assigned by the instructor), designed to be heterogenous versus homogenous by ability (e.g., Donovan et al., 2018), and permanent or transient during the course (e.g., Connell et al., 2023). It is important to note that equitable experiences within these active or cooperative strategies are not automatic. While social interactions can have positive benefits, they also have the potential to be problematic when instructors are not sensitive to power dynamics, racism, gender oppression, and other related issues. When these issues manifest in the classroom in problematic ways, they negatively affect underserved students. This issue has been most studied in regard to gender (Dasgupta et al., 2014; Dennehy & Dasgupta, 2017). Careful attention to designing activities with student attitudes, beliefs, and expectations about themselves, each other, their instructors, and learning itself is necessary and can mitigate these issues. Engaging students in co-creation of norms for classroom and group behavior can be helpful. Instructors can get started by reflecting on their own experiences and how they are similar to and different from those of their students (these issues are discussed in more depth in the next major section of this chapter). Professional learning and development can also be helpful for instructors to work together to develop and practice strategies (see Chapter 8 for more).

As mentioned above, when instructors ask students to work together, they should consider the features of groups and design instruction to ensure group members know how to work collaboratively (Johnson et al., 1998; Theobald et al., 2017), keeping in mind that the ultimate goal is practicing skills of the discipline vis-à-vis tasks that are enhanced with collaborative efforts (Dyer et al., 2013). It is also important to ensure that all group members are able to contribute by structuring activities in supportive ways and ensuring that students are not excluded from full participation in groups due to physical or sensory disabilities. Some students, especially those with disabilities, may need information to be provided in advance to allow for more processing time on expectations or to be ready to answer poll questions (Gin et al., 2020). Attending to composition of groups and assignment of roles for group tasks is important for fostering environments where students help each other solve problems by building on each other’s knowledge, asking each other questions, and suggesting ideas that an individual working alone might not have considered (Brown & Campione, 1994; Dasgupta et al., 2014; Ramsey et al., 2013; Sekaquaptewa & Thompson, 2003). Box 5-2 describes an approach to group work and collaboration that incorporates peer facilitators.

BOX 5-2

Encouraging Collaboration Through Peer-Led Team Learning

STEM-Dawgs Workshops at the University of Washington utilized a supplementary instruction (SI) model in an attempt to support students who are from groups that historically are underrepresented in general chemistry courses. Supplementary instruction means adding support to an existing course structure; in this case the STEM-Dawgs workshop was designed as a “weekly, two-hour, two-credit companion course for Chemistry 142, which is the first in the three-quarter (year-long) general chemistry sequence for majors” (Stanich et al., 2018).

The workshop first started with individual quiz and group work, followed by discussions on a pre-class writing exercise guided by the peer facilitators. Students then worked again in small groups to answer chemistry questions that are relevant to lecture and that required a range of thinking skills. The initiative used the Peer-led Team Learning (PLTL) approach, including sessions designed outside of the classroom with guidance provided by a peer leader. As an extension of the PLTL SI, and in addition to peer-facilitated problem-solving, STEM-Dawgs incorporate two components inspired by learning sciences: (a) research-based study skills, and (b) evidence-based interventions targeting psychological and emotional support. For example, before most workshops or at other specified times, students completed evidence-based writing intervention that addressed the barriers in stereotype threat, mindset, self-regulation, test anxiety, belonging, value of learning, expectancy value, and post-exam metacognition.

This use of supplementary instruction was found to help increase course performance and also other nonacademic outcomes such as sense of belonging for underrepresented minorities, females, low-income students, and first-generation students. Supportive peer-learning environment and relationships with peer facilitators partly contributed to the successes.

Group work of all kinds can also provide the instructor with an opportunity to interact with students to deepen relationships. An instructor can circulate among groups to listen in on conversation or provide real-time answers to questions. Group tasks and discussions also provide an informal assessment opportunity as the students’ comments and questions can provide insight into sticking points or areas where students are struggling. (See the section in this chapter on Assessing Learning and Providing Feedback for additional discussion about assessment strategies.)

Help Students Build upon Their Knowledge and Lived Experiences

As articulated in Principle 2, students’ prior knowledge and previous experiences set the foundation for new knowledge. Connecting to and

leveraging students’ prior knowledge and interests can enhance their learning. This includes formal knowledge in the STEM disciplines gained from previous schooling as well as students’ experiences outside of formal educational settings that are relevant to STEM learning. Many campus centers for teaching and learning provide guidance for instructors on approaches for activating this student knowledge (e.g., Virginia Tech,3 University of Texas, Austin4) as do the developers of the Universal Design for Learning guidelines discussed in greater detail above.5

One example of facilitating use of prior knowledge from a previous lecture involves posing a problem/question to the class at the beginning of lecture or when discussing a case study. Various tools can be used to activate student knowledge and help them to see if it is relevant to the course material (Bransford & Johnson, 1972; Brod, 2021; Hattan et al., 2024; Simonsmeier et al., 2022). Instructors can also implement forecasting, in which they provide a question/problem and ask students to make a prediction or to hypothesize based on their knowledge or past lectures (Byrne et al., 2010; Schwartz & Bransford, 1998). In other instances, understanding students’ prior knowledge allows the instructor to help students reflect on any alternative conceptions they may have (Fisher, 2004). There are many strategies instructors can use to activate prior knowledge, including using advanced graphic organizers, anticipation guides, problem solving with case studies, opening questions, and power previewing (skimming text strategically before reading in detail; Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, n.d.). In addition, instructors can provide resources to all students by posting supplemental materials or discussing options for obtaining support from peers, tutors, or other campus offices (Vega & Meaders, 2023); such resources may be especially helpful to those who do not have as strong a background in the relevant content area. As the next paragraph discusses, these types of strategies can help compensate for the variety of background and experiences of the students who enter a course and potentially help alleviate equity concerns.

Recognizing the diversity of experiences that students bring to the learning environment, leveraging it, and making connections between students’ everyday lives and STEM concepts and practices promotes more equitable outcomes (Bayles & Morrell, 2018; Booker & Campbell-Whatley, 2018). Students enter courses with knowledge from previous educational and life experiences. One way of conceptualizing this is the concept of funds

___________________

3 More information about guidance for instructors at Virginia Tech is available at https://teaching.vt.edu/teachingresources/adjustinginstruction/priorknowledge.html

4 More information about guidance for instructors at the University of Texas, Austin, is available at https://ctl.utexas.edu/prior-knowledge

5 https://udlguidelines.cast.org/representation/building-knowledge/prior-knowledge/

of knowledge, which encompasses the cultural, familial, and household experiences/knowledge/skills that students bring, and which can be leveraged to enhance their abilities to understand academic knowledge relevant to their coursework (González et al., 2005). Textbooks rarely provide these kinds of connections, but instructors can supplement the content of the texts (Meuler et al., 2023). In some studies, instructors provided opportunities for students to draw on the knowledge and skills they have developed within their communities and families, e.g., their existing funds of knowledge (González et al., 2005; Moll, 2019; Moll et al., 1992). Another way to connect students’ STEM learning to their experiences outside of the classroom is to provide opportunities for students to choose to study topics that are of personal or cultural relevance (Barnes & Brownell, 2017; Black et al., 2022; Dasgupta, 2023). Showing how science and engineering are socially relevant is also a strategy for connecting with students’ interests and has the potential to engage more diverse learners (Dasgupta, 2023). When instructors recognize that students can benefit from drawing on their families, cultural assets, and communities to which they belong, the instructors are better positioned to support deep and critical engagement of students with STEM content in their courses and classrooms (Bang & Medin, 2010; Bang et al., 2010; Covarrubias et al., 2019; Fryberg & Markus, 2007; Solyom et al., 2019). (See Chapter 4’s discussion of Principle 2 for additional strategies and approaches that leverage students’ cultural knowledge and experiences.)

Deepening Engagement in Disciplinary Knowledge and Work

As discussed above and in Chapter 4, active engagement in disciplinary content is critical for student learning. Several approaches can support this type of learning in and outside of class. The specific approaches may vary for foundational STEM courses versus the often-smaller upper-level courses. In large, high-structure courses pre-class preparatory assignments can be combined with in-class active learning activities such as think-pair-share, polling, and student surveys (Eddy & Hogan, 2014; Freeman et al., 2014; Haak et al., 2011; Theobald et al., 2020). In order for active learning to be equitable and effective it needs to be carefully designed to ensure that all students have the opportunity to participate and be successful and instructors may need support from their academic units or institutions to provide access to learning spaces that are well suited to approaches such as group work6 or to additional teaching assistants or undergraduate learning

___________________

6 As an example, see additional information about the SCALE-UP model of arranging classrooms for active learning is available at https://www.physport.org/methods/Section.cfm?G=SCALE_UP&S=What

assistants who can provide the workforce to support the implementation of the approaches (Dewsbury, 2020; Talbot et al., 2015; White et al., 2020).

While discipline-based active learning experiences in the classroom can advance students’ learning, students also benefit from opportunities to deepen their engagement in a discipline through participation in research (Malachowski et al., 2024; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017b). Undergraduate research is often cited as an invaluable learning experience for students across all disciplines, even those outside of the STEM field. For example, the High Impact Practices work done by the American Association of Colleges and Universities includes undergraduate research in their list of approaches based on evidence that can provide educational benefits for students.7 In STEM, engaging in undergraduate research has been shown to benefit diverse students from marginalized populations (Barlow & Villarejo, 2004; Chang et al., 2014; Harsh et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2010; Thiry & Laursen, 2011). Box 5-3 describes reported benefits of a program, Building Infrastructure Learning to Diversity: Promoting Opportunities for Diversity in Education Research (BUILD PODER), for supporting undergraduate research in the sciences that involves partnership between community colleges and a university. BUILD PODER8 is designed to build power, change campus culture, and nurture research mentoring relationships as it “helps students understand institutional policies and practices that may prevent them from persisting in higher education, learn to become their own advocates, and successfully confront social barriers and instances of inequities and discrimination” (Saetermoe et al., 2017, p. 42). Undergraduate research has been used as a tool for teaching and also a tool for transformation of learning experiences and curriculum. A longitudinal study to explore the role of undergraduate research in changes to institutional culture and student learning is documented in the book Transforming Academic Culture and Curriculum: Integrating and Scaffolding Research Throughout Undergraduate Education, which presents guides and toolkits designed to inform change agents (Malachowski et al., 2024).

Course-Based Undergraduate Research Experiences (CUREs)

CUREs offer students the chance to engage in authentic hands-on inquiry as a part of their normal coursework. It has been proposed as a way to expose more students to research as opportunities to work in laboratories are not available to everyone. Students enrolled in classes with CUREs

___________________

7 More information about the AAC&U’s High Impact Practices is available at https://www.aacu.org/trending-topics/high-impact

BOX 5-3

Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity: Promoting Opportunities for Diversity in Education and Research

This undergraduate research initiative involved 81 community college students and 41 community college faculty mentors working with California State University, Northridge (CSUN) so that the students could engage in research in STEM and biomedical disciplines. The program Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity: Promoting Opportunities for Diversity in Education and Research (BUILD PODER) shared some of the benefits of the program reported by the students:

- Gaining lab experience: A student reported their research experience gained through a summer laboratory experience has been essential in shaping and developing their science identity.

- Applying academic skills to real-world settings: A student reported through studying the impact of chemicals on plant growth, they learned important research skills such as operating scanning electron microscopes, making posters, and presenting scientific research at conferences.

- Learning the research process: A student reported enjoying working in the lab and reading research literature, which promoted their interest in biology.

- Building networking and support system: A student reported that being an undergraduate researcher provided opportunities to meet others and get needed support for transition from a community college to a baccalaureate institution.

- Developing collaboration skills and preparing future professionals: Students reported summer research experience improved collaborative skills and that mentorship helped inform educational and career paths.

This example demonstrates that baccalaureate-granting universities and community colleges have the capacity to foster interest in undergraduate research (Ashcroft et al., 2021). Additional research studies about the program can be found at https://www.csun.edu/build-poder/build-poder-publications-and-presentations.

learn about the scientific practices and generate new knowledge within their discipline. Over the past few years, CUREs have been used as a tool to improve undergraduate STEM classes while engaging a larger number of students in disciplinary practices (e.g., Werth et al., 2022). These courses have been linked to significantly positive outcomes among the students who participate, including higher levels of career achievement, higher levels of retention in class, in the major, and in college, and deeper comprehension of class material (Fitzsimmons et al., 1990; Hanauer et al., 2016; Lopatto, 2003; Mogk, 1993; Tomovic, 1994; Zydney et al., 2002). These courses

also increase access to research experiences for students who may not be aware that these skills are needed to advance in some areas (Bangera & Brownell, 2014).

CUREs can be found at various institutions across the country, although they are more readily supported at doctoral-granting institutions (Wei & Woodin, 2011). Historically, CUREs have been predominantly implemented in upper-level classes. However, in recent years, instructors of large, highly enrolled introductory courses and those at community colleges have begun adopting these practices (Cruz et al., 2020; Sexton & Sharma, 2021; Tomasik et al., 2013; Tuthill & Berestecky, 2017). A major benefit of these efforts is that many students are exposed to the benefits of CUREs as a part of their general education curriculum. In addition to learning valuable STEM skills, students who partake in research report increased confidence, communication, creativity, and collaborative skills (Ahmad & Al-Thani, 2022; National Academies, 2017; Starr et al., 2020). Importantly, they also claim to have a more personal connection to their area of interest. One study found that CUREs students at a Hispanic Serving Institution had significantly higher overall grades in a lecture course directly related to the CURE even after statistically adjusting for demographic and academic characteristics (Ing et al., 2021).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, several instructors and programs had to shift their research agenda to an online learning environment. In doing so, colleges nationwide began to explore alternatives to in-person labs and projects. Though there were concerns about students’ long-term transferable skills, studies indicate that students who participate in online research experience still show positive outcomes, such as higher levels in self-efficacy and retention in STEM programs (Erickson et al., 2022; Hess et al., 2023). CUREs are therefore a feasible approach for multiple class modalities (in-person, online, or hybrid).

Field Experiences

Engaging students in making observations and collecting data in the field is a hallmark of some STEM disciplines, including the geosciences (geology, environmental science, and marine sciences) and ecology (O’Connell et al., 2021). Field experiences can provide an opportunity for authentic investigation, in addition to offering a multitude of cognitive, affective, social, and professional benefits. The Undergraduate Field Experiences Research Network (UFERN) developed a model for designing and conducting field experiences that builds on an extensive literature review (O’Connell et al., 2022). As with any activity where learning is the goal, the UFERN model starts with setting intended student outcomes, then incorporates student

context factors (e.g., prior knowledge and skills, worldview, identity) and design factors (e.g., timing, orientation, social interactions, choice and control) to create a field experience that supports learning and accommodates all students. The student context and design factors reflect the Principles for Equitable and Effective Teaching and are important whether the field experience is a few hours long or a few weeks.

Virtual field experiences have become more common, in part because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and provide a technology-supported means for broadening access to the field. Recent research suggests that cognitive gains in virtual field experiences can be similar to those seen in real field experiences (e.g., Markowitz et al., 2018; Mead et al., 2019) and can overcome some of the commonly seen gender and race/ethnicity gaps experienced in in-person field experiences (Bitting et al., 2018). However, even as students and instructors hold negative perceptions of the virtual field experience (Bond et al., 2022) and report preferring in-person field experiences (Rader et al., 2021), these promising results provide support for the use of virtual field experiences when an in-person field experience is inaccessible for any reason.

Assessing Learning and Providing Feedback

Designing for learning requires monitoring whether and what students are learning. When assessments are designed to document progress toward carefully chosen learning outcomes, they can provide insights for both the student and instructor on how to improve. Assessment is a major component of Principle 5: Multiple forms of data. Assessment practices are a key strategy for supporting and advancing students’ progress, so it is essential to reflect on and modify these practices with the principles in mind to ensure that they are being applied in productive and supportive ways (Walvoord & Anderson, 2010).

As described in Chapter 4, assessments can be divided into two major types: (a) formative assessment which focuses on eliciting student thinking and gathering information that allows the instructor to adapt to student needs and (b) summative assessments that document how students have progressed in their learning and are often used to determine students’ grades. Summative assessments might also be used to evaluate the effectiveness of a course—that is, to determine whether the structure of the course and the tasks and activities for students have successfully advanced students’ learning.

Providing a variety of low-stakes opportunities for students to engage with course content, such as through reflection assignments, breaking large projects into multiple components, peer review of early drafts, or short quizzes, can help students make connections and understand concepts

without provoking as much anxiety as midterms and final exams. Frequent assessments can enhance retention of the concepts being covered in class and decrease the weights of each assignment. Including different types of assignments within a course allows students the opportunity to demonstrate their understanding in the formats that might work best for them. These strategies also provide multiple opportunities for feedback so that students and instructors can adapt their approaches during the course (Brame & Biel, 2015; Halamish & Bjork, 2011; Murphy et al., 2024).

Lower-stakes assessments may include laboratory work and reports, written assignments, weekly quizzes, homework, and small-value quizzes, etc. A discipline-based education research study by Cotner and Ballen (2017) describes an example of biology courses in which mixed assessments (not just high-stakes exams) were used and their positive impacts on female-identifying students. The study evaluated gender-based performance trends in nine high-enrollment introductory biology courses in Fall 2016. Course sizes ranged from 90 to 239 students. Grades were categorized as combined grades on midterms and finals, non-exam assessments, and a combination of exam grade and non-exam grade. The study verified that mixed assessment combining different approaches, such as group participation, low-stakes quizzes and assignments, and in-class activities, can minimize the impact of high-stakes exams for underrepresented groups in STEM.

Instructors can also provide varied types of assessments (both formative and summative) within a course or holistically in courses within the degree plan. Types of assessments can include individual/team projects, oral/poster presentations, collaborative group worksheets, individual/team videos along with exams and homework. Assessments may also be designed to build skills such as communication, teamwork, and leadership. Finally, instructors can allow for flexibility in having students show progress in their understanding by allowing students to submit multiple drafts or resubmit corrected work. This kind of flexibility reflects Principle 6: Flexibility and responsiveness. This is important for courses such as mathematical proof writing where students are introduced to putting their ideas and mathematics into writing and as such is different from previous computational courses.

Feedback and Messages About Assessments

How an instructor communicates about both the purposes of assessments and what the results of an assessment mean can have a strong impact on students’ perceptions of themselves, of the course, and of the discipline. Studies have shown that students’ perceptions of their instructors are predictive of engagement and performance (Canning et al., 2024; Muenks et al., 2024).

Messages about whether students’ success depends on innate ability (a fixed mindset) or depends on effort and learning (a growth mindset) have been shown to have particular importance for students’ motivation and performance (Canning et al., 2024; Muenks et al., 2020, 2024). Researchers have identified teaching behaviors that can foster and communicate to students that intelligence and ability are qualities they can develop through effort, good strategies, and seeking help when stuck (Kroeper et al., 2022a,b). Kroeper et al. identified four categories of teaching behaviors that influence whether students infer that an instructor has a growth mindset about their abilities. Two of these are particularly relevant to assessments. Students perceive instructors as having a growth mindset when

- instructors provide many opportunities for practice and provide frequent feedback to students; and

- instructors respond to students’ poor performance, struggles with learning, or confusion by providing support, suggesting strategies, and offering additional opportunities for improvement (rather than with frustration or implying that the student cannot improve).

Designing assessments that are clearly aligned to the stated learning goals for a course and then communicating the goals and expectations to students is critical. This information can be communicated in the course syllabus (see discussion of the syllabus later in this chapter) and in the descriptions of individual assignments. For example, assignments can lay out both the goal or purpose of the assignment and the specific criteria the student needs to include in their response (e.g., as a rubric or a list of points to address). Jonsson and Svingby (2007, p. 130) explain that “the reliable scoring of performance assessments can be enhanced by the use of rubrics” and that “rubrics seem to have the potential of promoting learning and/or improve instruction,” given that rubrics make grading criteria more explicit. Some research shows that transparency in teaching can increase students’ ability to persist in college and that this impact specifically helps first-generation college students (Winkelmes et al., 2019). This kind of clarity and transparency reflects Principle 7: Intentionality and transparency.

Grading Practices

Traditional grading methods typically involve returning a grade or a graded assignment to students (with no or minimal feedback) and continuing on with the next lecture with little or no means to allow students to reassess or improve their understanding of assessed learning objectives. It can be helpful for instructors to reflect on their goals for providing student feedback and how that interacts with their approach to grading (Winstone

& Boud, 2020). There are many alternative approaches to grading that can be adopted in whole or in part to increase the feedback that students and instructors have about learning. Alternative grading methods (including specifications-based grading, standards-based grading, mastery-based grading, and ungrading, among others) are student centered and focus on using learning objectives to permit students to assess their performance in order to improve their understanding and meet the learning objectives (Blum, 2020; Clark & Talbert, 2023; Ferns et al., 2021; Hackerson et al., 2024; Stommel, 2024; Toledo & Dubias, 2017). Alternative grading methods may also help students adopt more of a growth mindset about their skills and abilities (Blum, 2020; Dweck, 2006; Ferns et al., 2021; Stommel, 2024).

Clark and Talbert (2023) discuss the four pillars of alternative grading (clearly defined standards, helpful feedback, grades indicate progress, and re-attempts without penalty), and provide distinctions on various types of alternative grading methods that can be implemented in small-sized and large-sized classes. Mastery-based grading (also called mastery-based testing or MBT) focuses on the student learning process and measuring student understanding of clearly defined learning goals, it has been promoted as a way to improve equity (Alex, 2022; Livers et al., 2024; Perez & Verdin, 2022; Winget & Persky, 2012). Several studies have examined MBT in undergraduate mathematics courses and some preliminary results suggest it may be helpful for decreasing student anxiety and supporting learning (Campbell et al., 2020; Curley & Downey, 2024; Dempsey & Huber, 2020; Harsy et al., 2021; Lewis, 2020). Specifications grading sets out pre-determined criteria that a student knows in advance and works to meet by completing assignments. Graves (2023) provides a brief literature review of implementations of specifications grading in various courses in different disciplines. Katzman et al. (2021) report more positive student attitudes and improved performance on content-related assessment questions in an undergraduate cell biology course using specifications grading. Alternative grading approaches have been explored in chemistry courses as well (Diegelman-Parente, 2011; Noell et al., 2023). These grading approaches have also been reported to motivate students to learn, discourage cheating, give students agency over their own grades, minimize conflicts between student and faculty on grade disagreements, and foster higher-order cognitive development and creativity (Clark & Talbert 2023; Nilson, 2015).

Technology to Support Monitoring of Student Learning

Using technological tools to track real-time data about students can allow instructors to monitor student status and progress through an online interface that displays learning analytics. Instead of traditional grades from summative assessments, robust dashboards can provide real-time

information not only on assessment outcomes but also on course activity and other measures of student engagement (Psaromiligkos et al., 2011; Rabelo et al., 2024; Sáiz-Manzanares et al., 2021). For example, an instructor might monitor or track student engagement (e.g., which students watch a particular video) to allow them to follow up with those who did not. These dashboards provide data directly from students and so may help minimize potential implicit bias effects in faculty (Arnold & Pistilli, 2012). The data can also be used by instructors to look at specific student use and assignment outcomes based on student demographic data (see examples of visualizations from data dashboards in Chapter 8). These learning management systems also provide student access, which may provide students with information on their own use relative to the rest of the class.

Technology coupled with learning science has been proposed as a tool that could lead to adaptive learning activities and courseware that might have the potential to improve access and equity by providing personalized learning experiences for students (Gordon et al., 2024). While many examples of courseware have been developed and studies have begun, the promise of the technology has not been conclusively established. A joint project involving four institutions that are members of the Association of Public and Land Grant Universities examined student and faculty perspectives on using adaptive courseware for undergraduate biology courses for non-majors. Results showed some positive impacts on student pass rates and some concerns about aspects of implementation related to both technical challenges and navigating unfamiliar ways of receiving feedback (Buchan et al., 2020; O’Sullivan et al., 2020). Courseware has the potential to include both formative and summative assessments as well as professional learning supports for instructors. The idea is that the approach can pinpoint areas where students are experiencing additional challenges and help guide the instructor in adapting their lessons to support students who may benefit from additional activities or from engaging with the material in a different way. Carnegie Mellon University’s Open Learning Initiative9 has been collecting and interpreting data over time with a goal of improving learning efficiency and overall outcomes mediated both by software-driven support directly to the student as well as faculty evidence-based interventions based on student learning outcome analyses (Bier et al., 2019, 2023).

___________________

9 More information about Carnegie Mellon University’s Open Learning Initiative is available at https://oli.cmu.edu/

CULTIVATING AN EQUITABLE AND EFFECTIVE LEARNING ENVIRONMENT

Students’ learning and motivation are strongly influenced by many elements of course design that come together to shape students’ experiences in a classroom or other learning setting. Indeed, the structure and situational cues in a learning environment—such as what an instructor says and does while teaching and/or the numerical representation of students in the classroom—impact students’ attention and their ability to marshal the cognitive and affective resources to engage in the processes essential to learning including encoding, storage, and retrieval of information (e.g., Cohen et al.,1999; Murphy & Taylor, 2012; Murphy et al., 2007; Steele et al., 2002).

In the first part of this chapter, we touched on many of the elements of classroom instruction and organization that shape students’ experience including tasks and activities, group work, and assessments. In this section, we turn to other elements of course design that are critical for creating a productive learning environment including the relationships between the instructor and the students, relationships among the students themselves, the cues students receive in the classroom about their own competence and belonging, and students’ opportunities for autonomy and choice. These latter elements are related to Principle 3: Affective and social dimensions, Principle 4: Identity and a sense of belonging, and Principle 6: Flexibility and responsiveness. In thinking about how to create a productive learning environment, instructors can use this set of three Principles to reflect on how to implement the many elements described in the first section: tasks and activities for students, organization of group work, engagement in research, and use of assessment. In this way, the Principles are helpful for thinking about both what students should be doing in the classroom and how instruction and interactions can be organized to help students feel supported and valued.

Students’ perception of and relationship with the instructor is particularly consequential for student learning and motivation. In one study, students in STEM courses and majors identified qualities they valued most in their instructors: a genuine desire for students to succeed, and authentic displays of respect and encouragement (Harper et al., 2019). Research also indicates that students experience greater self-efficacy, sense of belonging, and academic achievement when instructors show care and respect for all students (Christe, 2013; Micari & Pazos, 2012). Effective and equitable teaching is grounded in the approach of mutual respect. Instructors can focus on establishing that respectful culture in order to foster their primary goal of supporting student learning.

One way for instructors to approach how to create a productive learning environment is to consider the students’ point of view and reflect on the

planned approach and its implications for equity and student learning. This can involve many aspects of course preparation. Reconsidering the syllabus in light of effective and equitable teaching can make it a more useful tool; reviewing choices of instructional resources can lead to materials that are more effective and more equitable; and taking a new approach to getting to know students can help the instructor to make the course more student centered.

Reflecting on Your Own Assumptions

Instructors’ knowledge and beliefs about their students influence their teaching and their students’ learning. There are multiple frameworks that can help an instructor understand how they perceive students’ identities and experiences (Shukla et al., 2022). A commonly used framing to describe an instructor’s beliefs is categorizing them as deficit- or asset-based perspectives. A deficit-based perspective is one in which the tendency is “to locate the source of academic problems in deficiencies within students, their families, their communities, or their membership in social categories (such as race and gender)” (Peck, 2020, p. 940). Adopting an asset-based perspective means focusing on the knowledge and skills students have when they arrive in a course and seeing them as important assets to build on, even when that knowledge and experience may not align with educational norms. Through an asset lens, students are seen as bringing rich, diverse backgrounds and experiences with them into their undergraduate STEM classes that can serve as launch points for discussions and opportunities to apply STEM methods to questions of interest (Jaimes, 2021; Johnson, & Bozeman, 2012; Williams, 2021).

Beliefs about learning itself and about learning in a particular discipline are also important for instructors to surface. This can involve instructors reflecting on the mindset that guides their instructional practices. As discussed in Chapter 4, numerous studies have explored the differences between fixed mindsets and growth mindsets and the impact they can have on learning (Canning et al., 2019, 2022, 2024; Hecht et al., 2023; Muenks et al., 2020). A growth mindset is the belief that intelligence and abilities can be developed through practice and hard work. In contrast, a fixed mindset is the belief that intelligence is fixed (Dweck, 2006).

This mindset—whether fixed or growth—can profoundly impact an instructor’s instructional practices and, in turn, students’ experience of learning. The mindset beliefs that instructors hold about students’ abilities and how these beliefs are communicated through their teaching practices can be predictive of students’ experiences and success (Canning et al., 2019, 2022; Kroeper et al., 2022a,b; Muenks et al., 2020). When instructors hold fixed-mindset beliefs about their students (e.g., that their students’ abilities

and intelligence cannot change), students become more psychologically vulnerable, more likely to experience imposter syndrome, have negative experiences, and receive lower grades. The impact of these effects is disproportionally greater for underserved students; that is, STEM faculty who believe ability is fixed experience larger racial achievement gaps (Canning et al., 2019; Muenks et al., 2020). In contrast, holding growth-mindset beliefs about students and engaging in growth-minded teaching practices has a positive impact on student motivation, participation, and grades (Canning et al., 2024; Muenks et al., 2024; Murphy, 2024). Students also bring different mindsets to the course, including the beliefs they hold about learning and their perceptions of the beliefs their instructors hold. As discussed in Principle 3: Affective and social dimensions, feedback from instructors, the design of activities, and grading practices of instructors can impact student mindsets; when instructors are aware of their own assumptions and reflect on the mindsets of their students they are better able to offer equitable and effective instruction.

Getting to Know Students

Getting to know students is an essential part of an instructor’s work in teaching and learning, given the important roles of social and affective dimensions (Principle 3: Affective and social dimensions). Understanding their students’ interests and goals, prior knowledge, experiences, and needs will help instructors create an inclusive classroom environment and design or refine their class activities to create more effective learning experiences by connecting to and leveraging students’ identity, sense of belonging, interests, and goals.

In many college classrooms, students come from a range of backgrounds and life experiences which may be very different from the background and experiences of the instructor. The reality is that as the diversity of students in higher education increases (see Chapter 2), so does the variation of students’ prior knowledge and experience. Qualitative and quantitative data can help instructors get to know their students. Descriptive data, such as surveys or questionnaires, can be used to ask students about their experiences and potential challenges that they may face academically and personally. Instructors can use surveys to learn about students’ backgrounds, characteristics, interests, previous experiences, and any other pieces of information that can assist in the learning process. One example is the PERTS Ascend survey and accompanying tools.10 This system collects real-time information about how students are experiencing a course and provides the feedback to instructors to allow them to adjust their instruction and is

___________________

10 More information about the PERTS Ascend survey is available at www.perts.net/ascend

based on research from the Student Experience Project (SEP) and Equity Accelerator11 (Boucher et al., 2021).

Instructors can use disaggregated data about the students they teach coupled with surveys to gain access to information about their students, such as majors, experience with campus, first-generation status, work and family responsibilities outside of school, performance in prerequisite classes, and more, useful to instruction and course design. This can helpfully broaden the instructors’ perspective on who is in their classroom. Public universities in California (University of California, Davis, University of California, Irvine, University of California, Santa Barbara, California State University system), Michigan, and Nebraska, among others, have piloted such “Know Your Students” approaches, often coupled with suggestions and materials for faculty to support their students from varied backgrounds. Some of the Know Your Students tools specifically highlight key metrics based on factors such as course grade and completion, bringing in data from all the times an instructor has taught a specific course while putting it in context of course instances and student factors. Most importantly these tools have specifically been designed to support individual faculty reflection on their teaching approaches and student outcomes, not as judgment of teaching effectiveness. The data shared are often only accessible to the individual faculty, further solidifying the non-judgmental focus of the approach. These more robust data gathering approaches may require support from departments or institutions and may be challenging for some instructors to implement. Other more accessible approaches to getting to know students are described in the sections below.

Chapter 8 further discusses ways that data of this sort can be used to inform continuous improvement on the instructor, academic unit, or institution level, and Chapter 9 gives more information on how institutions can support instructors to learn about their students and how the institutions can use data to improve policies and procedures.

Before Classes Begin

Prior to the first day of class, instructors can start the process of getting to know their students by reviewing any campus-provided data and introducing a pre-course survey. This survey can come in many forms, such as an online assessment or quiz, a paper questionnaire, or a private discussion post in the course’s learning management system. Instructors can determine

___________________

11 More information about the Indiana University Equity Accelerator and its connection to SEP is available at https://accelerateequity.org/resource/case-study-student-experience-project/ and more information about the SEP is available at https://s45004.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/Increasing-Equity-in-Student-Experience-Findings-from-a-National-Collaborative.pdf

what students already know or can do through low-stakes assessments, such as assignments that give students the opportunity to bridge their preknowledge and skills with what they will learn in a course (Ghanat et al., 2016; Landrum & Mullock, 2007; van Barneveld & DeWaard, 2021). As discussed above in the section “Help Students Build upon Their Knowledge and Lived Experiences,” there are many strategies that can build on students’ culture and prior experience. These tools can help instructors learn about who their students are, their goals for the course, and their learning needs. Pre-course surveys might include

- A demographic questionnaire with guided questions. The prompts are written to help the instructor get a better sense of the student’s background and create a space for the student to share important information that they want their instructor to know. This can be a physical handout for an in-person class or an online activity for a large online class. Prompts can be as broad as “What should I know about you that would help me help you learn better?” or as specific as “What do you prefer to be called? What are your pronouns?”

- Questions about students’ goals for the course or their learning preferences: “What do you want to get out of this course?” or “How do you learn best?” This can be done anonymously to encourage honest answers, and it can be incorporated into the first day of class.

Ultimately, the goal is for the instructor to gain a better understanding of who their students are and practice recognizing differences among our students. “Equitable practice and policies are designed to accommodate differences in the contexts of student’s learning—not to treat all students the same” (Center for Urban Education, Rossier School of Education, 2015, p. 1). The information gathered from pre-course surveys can help the instructor build connections with students and consider how to better support students during the course.

Engaging with Students in and out of Class

Instructors can learn a great deal about their students just by talking to them. Principle 2: Leveraging diverse interests, goals, knowledge, and experiences, emphasizes the importance of developing connections with students. Students who have a working relationship with their instructors are more likely to be successful in class (Bolkan & Goodboy, 2009; Hagenauer & Volet, 2014). This relationship is especially crucial in higher-level classes in STEM (Micari & Pazos, 2012), and in more career-oriented programs

such as nursing (Al-Hussami et al., 2011). Using active learning strategies and engaging students in group work can open up additional opportunities for instructors to engage with students informally during class time by circulating and listening in as students work on tasks and participate in small group discussions. Normalizing help-seeking behavior can change students’ attitudes about their learning and improve their experiences with STEM courses (Oh, 2020; Won & Chang, 2024).

Office hours provide opportunities for instructors to provide help and to interact with their students as they discuss course material or other related interests in a less formal setting outside of class. Many students do not take advantage of professor office hours, sometimes because they are not familiar with the concept of office hours or are not sure if their presence would be welcomed. An important step in getting students to come to the office hours is to define the purpose of office hours—emphasizing that office hours are there to serve the students. These time blocks act as an extra opportunity for students to engage with professors outside of the main learning environment and can provide a venue for reflection on the course material. One way to make office hours more useful is to improve accessibility, and instructors can try to find creative ways to get students to reduce barriers to attendance. They might hold office hours in a laboratory, at the bookstore or coffee shop, or as a group meetup in a campus lounge (Gao et al., 2022; Guerrero & Rod, 2013; Stephens-Martinez & Railling, 2019). For professors in an online class, office hours typically tend to be held virtually. These too can be tailored to bring more students in. Virtual office hours can offer sessions that go over a fun weekly concept (e.g., review a new article relevant to something that was discussed in class or present a case study for participants to analyze).

A simple change from the name office hours to “student hours” can also help to emphasize who this time is for, and movement has begun to rename and re-envision office hours in this way, so as to better demonstrate their purpose to students (Benaduce & Brinn, 2024; Cafferty, 2021; Mowreader, 2023). It is important to acknowledge that some institutions may not require all faculty to conduct regular office hours or may not compensate them for this time. For instance, part-time or adjunct professors may only be required to teach their class during the assigned hours. Academic units and institutions may consider compensating part-time or adjunct faculty for the work they do outside of class, and that work should include office hours.

Midterm Check-ins

Check-ins can help to catch students who are at risk before too much time passes. A midterm check-in—perhaps using the learning management

system with all students or asking a colleague to conduct a small-group evaluation—can help assess what is working and not working. Check-ins, whether midterm or at other times, can be valuable resources to both students and instructors. For students, these check-ins give them an active role in the learning environment. Furthermore, students who may be unaware of their low performance are given the opportunity to turn their grade around before the term is over (Overall & Marsh, 1979). For instructors, check-ins can guide course adjustments to meet students’ interests and needs. Incorporating student feedback as a part of the curriculum also empowers students to have a voice and leads to continuous improvement in teaching (Diamond, 2004). Some data suggest that students who identify as first-generation, low-income, and/or underrepresented minoritized college students may benefit from this practice (Kitchen et al., 2020). Educators who implement midterm check-ins create opportunities to address hidden concerns that may be affecting students’ learning (Bullock, 2003). Additionally, instructors who use check-ins report receiving more positive course evaluations at the end of the term (Keutzer, 1993). Note that check-ins also provide an opportunity to build relationships between the instructor and students. The importance of the instructor-student relationship is discussed in other sections of the chapter and relates to Principle 3: Affective and social dimensions.

Creating a Sense of Community and Belonging

As described in Chapter 4 in the section on Principle 4: Identity and a sense of belonging, sense of belonging refers to a student’s personal relationships in a given environment and their feelings about being accepted, valued, included, and encouraged (Betz et al., 2021; Espinosa, 2011; Newell & Ulrich, 2022; White et al., 2020). Belonging influences academic motivation, academic achievement, and well-being in students, and has been shown to influence student retention and persistence (Cavanagh et al., 2018; Eddy et al., 2015; Hansen et al., 2023; Ream et al., 2014; Steele, 1997; Steele et al., 2002; Strayhorn, 2018; Trujillo & Tanner, 2014). Instructors can create opportunities for faculty-student and student-student engagements to build interpersonal relationships through class discussions and class group work. To build on students’ disciplinary identity in classes, instructors can introduce contributions made by diverse groups of STEM professionals that reflect the demographics of students in the class, along with providing a class environment where students can talk and discuss STEM concepts. Instructors can also provide students with opportunities to share their reasons or personal interests for majoring in STEM especially during beginning-of-the-year class introductions.

Research in multiple disciplines shows that interventions designed to enhance students’ sense of belonging can be powerful. Rainey et al. (2018) found four key factors to contribute to a sense of belonging for students (independent of race or gender): interpersonal relationships, perceived competence, personal interest, and science identity. The classroom climate has been shown to be a critical factor in computing disciplines, where students “are exposed to the skills and knowledge, knowledge presentation, and expectations about the kinds of people who belong (or not) in a degree program” (Barker et al., 2014, p. 2). Changing student contexts, such as by increasing cross-gender interactions in class and other approaches that challenge identity-based stereotypes, can improve feelings of belonging and student performance (Binning et al., 2020, 2024). Like normalizing help-seeking behavior as discussed above in the section on getting to know students, short interventions can let students know that it is normal, common, and usually temporary to have social and academic setbacks and challenges as they transition to college and can help them realize that challenges do not mean they should leave the field of STEM or their pursuit of higher education (LaCosse et al., 2020; Walton et al., 2023).