1

Introduction

On March 20 and 21, 2023, the Board on Science Education at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine hosted a workshop titled Effective Health Communication within the Current Information Environment and the Role of the Federal Government. Workshop speakers and participants, a majority of whom were working in government agencies in federal health communication or leadership positions, joined both in person in Washington, D.C., as well as virtually to consider ways to enhance capacity for effective health communication in the federal government. A planning committee appointed by the National Academies planned the workshop in accordance with a Statement of Task (Box 1-1), with the goals of:

- Exploring the current health information environment and other forces that affect federal health communication;

- Examining the goals and roles of federal health agencies within this information environment;

- Identifying concrete steps for building capacities needed across the U.S. government to support effective health communication moving forward; and

- Identifying ways for the federal government to keep current on the ever-evolving health information environment through research, coordinated learning activities, and/or communities of practice.

“The overall goal of effective health communications is to protect and improve the public health,” stated William Hallman, Professor and Chair of

the Department of Human Ecology at Rutgers University and Chair of the Planning Committee. Much of what the federal government does, Hallman said, focuses on addressing infectious and noninfectious diseases, regulating prescription drugs, addressing occupational hazards and environmental contaminants, ensuring highway safety, preparing for and recovering from natural disasters, and many other activities that directly impact public health. In all these activities, effective communication is a fundamental part of protecting and improving public health. Toward that larger aim, this workshop, said Hallman, was designed to examine the goals and roles of federal health communication, consider the challenges that need to be addressed to improve efforts, and discuss viable solutions to these challenges in both the short and long term.

The workshop was organized around five capacities that need to be developed for effective health communication in the federal context. This introductory chapter summarizes conversations about the importance of effective health communication and the goals, roles, and responsibilities of federal health communication. Chapter 2 examines the cross-cutting

challenges in health communication and their implications for capacity building. Chapters 3–7 explore various capacities needed in the federal government for effective health communication: listening to and engaging communities, digital data and information systems, expertise and human capital, organizational capacities for agility, and building relationships. Finally, Chapter 8 features key themes that emerged during the workshop and speakers’ and participants’ thoughts on next steps. Appendices provide the workshop agenda, biographical sketches for the planning committee and panelists, and insights from breakout group discussions related to building capacity for community engagement, data and information systems, and human capital and expertise.

GOALS AND ROLES OF FEDERAL HEALTH COMMUNICATION

Many federal agencies communicate about health as part of their core missions to improve the well-being of Americans, as well as during times of crisis, stated Hallman. Being explicit about the varying objectives for health communication and the appropriate roles and responsibilities of federal agencies is vital for determining the capacities needed. This workshop session offered an overview of the types of key health communication goals, roles, and responsibilities of federal agencies, and explored the implications of these for decision making and building trust and credibility.

Effective health communication is defined by more than making decisions about appropriate messaging and public relations, said Hallman. While much attention is given to determining the message to be conveyed, effective health communication is part of a much broader process of engaging with stakeholders. Stakeholder engagement is a critical part of communication, providing insight into which health issues concern the community, what questions they want answered, and what misinformation may need to be addressed. Stakeholders “know things that we do not know and have perspectives that we do not have,” said Hallman, and the combination of government and community knowledge and perspectives can improve decisions. In addition, the process of engaging with stakeholders can help achieve consensus, can help anticipate how different stakeholders may react to a given message, and can identify areas in which there may be pushback or counter-messaging. Engagement with stakeholders is also an important part of evaluation, said Hallman. Evaluating the effectiveness of government efforts requires assessing whether messages are understood, reaching the right people, connecting with people’s lived experiences, and having the intended impact.

According to Hallman, federal agencies play many roles with respect to authoritative health information, as shown in Box 1-2.

The question, said Hallman, is what role should federal agencies play? The appropriate role may be determined by law, by public expectations, or by an agency’s unique ability to collect and analyze information. When not established by law, an agency’s role is influenced by its available expertise and resources; its perceived trust and credibility; and the need for agility, timeliness, openness, transparency, and accountability.

Agencies may employ multiple strategies in using authoritative information to influence health behaviors, said Hallman. These strategies may be designed to inform, educate, warn, advise, nudge, persuade, incentivize,

or coerce. Deciding which strategy to use is not always straightforward, he said, and it is important to examine who decides on the strategy and on what basis. In addition to messaging designed to educate or change behavior, federal agencies may also engage in messaging designed to maintain trust and credibility. An agency may share information with the public about how decisions were made, what information was used, what options were considered, and what risks and benefits were balanced. This type of messaging, said Hallman, may be used to promote transparency or to communicate uncertainty during a time of crisis.

Panelists addressed critical functions of health communication and considerations for fulfilling the various goals and roles the federal government has for effective health communication. Presentations addressed the vital importance of ensuring that shorter-term communication goals and strategies support longer-term goals of strengthening trust, credibility, transparency, and democratic institutions and processes.

HEALTH COMMUNICATION: CONNECTING SCIENCE, PRACTICE, AND POLICY

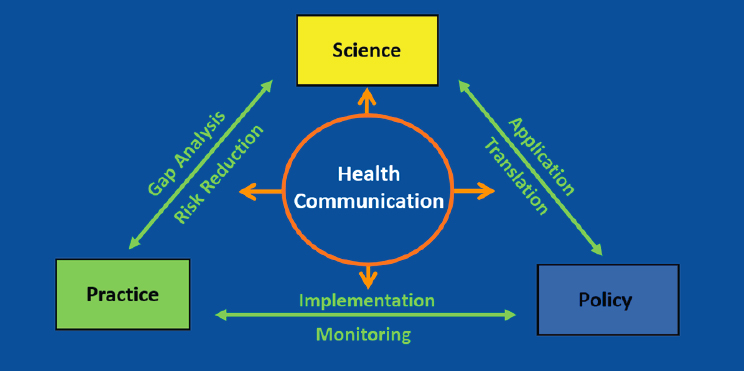

Health communication is a science, said Maureen Lichtveld, Dean of the School of Public Health, the Jonas Salk Chair in Population Health, and Professor of Environmental and Occupational Health at the University of Pittsburgh, setting the stage for the discussion of health communication goals. Lichtveld presented a framework illustrating how health communication influences each interaction between science, policy, and practice (Figure 1-1). Policy needs to be informed by the application and translation of scientific findings, she said, and this relationship requires effective health communication. For policy to become practice, stakeholders need to use health communication to both implement and monitor the process. Finally, practice can impact science through identifying gaps in knowledge; and science can impact practice through identifying potential areas for risk reduction—both of which require effective health communication. The federal government, said Lichtveld, has a role to play in all these areas.

It is critical, said Lichtveld, that any communication framework begins by considering the target audience. She stressed that the target audience needs to be considered before a crisis occurs, which requires early engagement and relationship building. If these relationships are not in place before a crisis, messages from the federal government may not be the first ones heard, damaging government’s influence and credibility with its target audience. It is important for the federal government to seek to be first, to be right, and to be credible, she said. The way that a message is delivered is also essential, and the optimal delivery method varies depending on the message and the target audience.

SOURCE: Presentation by Maureen Lichtveld, March 20, 2023.

While health communication and disaster management are not identical processes, there are important lessons from disaster management that can be applied to health communication, said Lichtveld. Preparedness is the most important part of disaster management, yet it usually receives the least attention and investment. The same is true of health communication: during the “preparedness” phase, capacity is built, and trust and credibility are developed. In the response phase of disaster management, coordination between agencies and stakeholders is key. Disaster management includes a phase called the “hot wash,” in which stakeholders take a step back and identify lessons learned. Finally, in the recovery phase, sustained partnerships need to happen. Instead of leaving communities after a disaster, said Lichtveld, the recovery phase is the time to fortify the relationships that have been built, to sustain them for the future. The coordination, ongoing learning, and relationship-building steps are equally important for health communication, explained Lichtveld.

INCREASING CREDIBILITY: AN ALTERNATIVE TO “FOLLOW THE SCIENCE”

Effective health communication requires credibility, said Arthur Lupia, Professor of Political Science at the University of Michigan. Credibility is not a constant or a trait. Rather, credibility is earned “every day and through every interaction,” according to Lupia. There are various sources of credibility, explained Lupia. Scientists can gain credibility by using the

scientific method, which produces intersubjective knowledge—that is, the validity of the findings does not depend on who conducted the study. Other members of society gain credibility in different ways. For example, politicians can gain credibility by articulating their values, particularly if those values resonate with others.

There can sometimes be tension between making statements that influence opinions in the short term and remaining credible in the long term, said Lupia. While evidence can inform policy, evidence alone is insufficient to resolve many moral and ethical issues associated with policy recommendations. Instead, factors including values, feelings, beliefs, and politics inform policy recommendations. Confounding scientific claims with policy recommendations can diminish the credibility of the scientist, he explained. Science is a powerful cultural force and anyone who speaks on its behalf has a “huge obligation to really stay true to the method,” said Lupia. When scientific authority figures make policy recommendations based on factors other than science without revealing that fact, it becomes easier for others to discredit the authority figures’ credibility, he said. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many communicators said, “follow the science, take the vaccine.” While this advice has some scientific basis, it also relies on values and tradeoffs that are not strictly scientific. Failing to clarify the role of science in a policy recommendation can mislead people about the true content of scientific studies and decrease their trust in future scientific claims, said Lupia.

Credibility can rise or fall, it can be built or rebuilt, but increasing credibility requires a strategy, according to Lupia. He shared a template for increasing credibility in health communication (Table 1-1). Following this template can empower people to make statements that are meaningful in the short term and credibility enhancing in the long term.

TABLE 1-1 A Template for Increasing Credibility

| TYPE OF CLAIM | MODEL STATEMENT | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|---|

| Claims about a scientific finding without policy or behavioral implications | “Study A produced Finding B.” | “mRNA COVID vaccine clinical trials showed B.” |

| Claims about a scientific finding being used to support a policy or behavioral recommendation | “Our values are X. Research shows Y. Based on X and Y, we recommend Z.” | “If you want to reduce your risk of dying from COVID, take the vaccine” (not “Follow the science, take the vaccine.”) |

SOURCE: Adapted from presentation by Arthur Lupia, March 20, 2023.

TIMELINESS AND TRANSPARENCY: LESSONS LEARNED FROM COVID-19 REAL-TIME REPORTING

Lauren Gardner, Professor in the Department of Civil and Systems Engineering at the Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering and Bloomberg School of Public Health, spoke to participants about her experiences developing and running the COVID-19 Dashboard at Johns Hopkins.1 This tool—which collected data on every officially reported COVID-19 case, death, and vaccination in any country—was built from scratch during the early days of the pandemic, in response to overwhelming demand for information. It was like “building an airplane while flying it in the worst lightning storm ever,” said Gardner. Building the infrastructure and capabilities to collect, validate, and report COVID-19-related data in the midst of the pandemic was “not how things should be done,” she said—there is a need for underlying systems and infrastructure developed and designed ahead of time.

Gardner gave workshop participants an overview of the challenges that arose when building the COVID-19 Dashboard and collecting data. She noted that, while some challenges were specific to COVID-19 and to operating in a “noisy and chaotic environment,” other challenges were more general. First, she said, parameter definitions were ambiguous. The definition of COVID-19 cases and deaths changed and evolved over time and between countries, as testing and technologies evolved. Even within the United States, she said, different states and counties used different definitions, which made direct comparisons difficult. Inconsistencies and instability were also present in the way cases and deaths were reported; for example, some locations reported retrospectively or reported data in info-graphics that were not machine readable. In addition, locations sometimes changed the way they provided data, requiring researchers to be responsive and adapt nimbly. Gardner said that data-reporting guidelines would have been extremely useful to reduce disparities among authoritative reporting entities. An anomaly-detection system, which could find differences in reporting for the same geographic region, was one strategy that researchers used to cope with disparities. Finally, variability in frequency and time-of-day reporting across locations was a major challenge in maintaining real-time reporting.

For data to be actionable, said Gardner, they need to be timely and at resolutions useful for decision making. Drawing on a paper she co-authored on the importance of open public data standards and sharing (Gardner et al., 2020), Gardner emphasized the need for a standardized data-reporting system for emerging infectious and notifiable diseases. Such standardization

___________________

is essential for generating actionable data, she explained, because it enables data to be systematically collected, visualized, and shared—all transparently and in real time.

Establishing a system before a crisis arises will ensure that sound and timely decisions can be made and can help establish public trust, she said. Gardner shared her views on Johns Hopkins’ success collecting and reporting real-time COVID-19 data, and the lessons this effort may hold for others moving forward.

The COVID-19 Dashboard project was developed in a supportive environment that included initial internal funding and later philanthropic funding. Gardner stressed that, moving forward, science agencies and governments need a better mechanism to quickly provide financial support to these types of efforts. She stated that Johns Hopkins University had the technical skillsets required to implement the work; and she noted that integrating engineers, computer scientists, and software developers into public health agencies is advantageous for providing such expertise. In addition, the team had the freedom to make executive decisions in real time, free from bureaucratic approval processes. Gardner noted that this was particularly critical in the early days when the pandemic was rapidly changing. In the future, she said, to effectively aggregate, centralize, and democratize public health data in real time, better open data standards are needed and the infrastructure and process need to be in place prior to the crisis. Finally, Johns Hopkins is a world leader in public health and medicine, and it is a nonpartisan institution. These qualities of the university allowed their project to be trusted and seen as accurately representing the data and science, as opposed to promoting an underlying agenda.

Gardner closed by sharing her perspective on the importance of high-quality, transparent data sources to drive evidence-based policy and decision making. Transparency and consistency are critical to promoting good science, said Gardner. When decisions or policies are based on scientific findings, a clear framework is needed to translate science into policy, and the entire process needs to be transparent and acknowledge the factors contributing to the decision. Consistency of this process over time can help build and maintain trust. When people do not understand how or why a decision was made, noted Gardner, they are less likely to trust that decision.

One participant stated that the federal government can be risk averse in its messaging—that is, it sometimes seeks to protect people through a lack of transparency about the real risks. During discussion, Lichtveld illustrated this point and the importance of transparency with an example from her work in the Gulf of Mexico following the 2010 oil spill. To convey that the risk to human health from consuming shrimp was not severe, a federal official developed a risk assessment that used a 90-kilogram person eating a 13-gram serving of shrimp. At a community meeting, a Vietnamese

fisherman explained that 13 grams was four shrimp, and a more realistic serving size was far higher. In addition, said Lichtveld, the average Vietnamese fisherman in the area weighed much less than the weight used in the estimate. If the estimate had used local information and local context, the well-intentioned messaging would have been much more effective. Lichtveld reiterated that increasing trust and communication between authorities and communities requires sustained partnerships and presence, even during the periods between disasters.

ETHICAL HEALTH COMMUNICATION IN A DEMOCRACY: INSIGHTS FROM EUROPE

Laura Smillie, Project Leader of the European Commission’s Enlightenment 2.0 research program at the Joint Research Centre, shared insights from this project. This multiannual research program aims to understand how the policy process can be optimally informed with the best possible evidence. The program’s latest project is looking at trustworthy public communication while grappling with the tension between two goals, Smillie said. First, the European Commission wants to ensure that its messages are meaningful and resonate with the 450 million people across 27 member states. Second, as a democratic organization with democratic values, the Commission wants to ensure that its messaging tactics are ethical and cannot be used by others who seek to undermine democratic values. For example, the Commission is exploring the boundary between informing/persuading and manipulating/coercing.

In recent years, the Joint Research Centre has released several reports that explore issues related to this aim. A 2019 report, Understanding Our Political Nature, examined key challenges for 21st-century policy makers, such as collective intelligence; understanding myths and disinformation; the role of emotion, values, and identities; and the role of openness and transparency (Mair et al., 2019). This report, said Smillie, recognized that evidence-informed policy goes hand-in-hand with the values that underpin democratic societies and cannot be taken for granted. A 2020 report, Technology and Democracy, explored the influence of online technologies on political behavior and decision making (Lewandowsky et al., 2020), while a 2021 report looked at the role that values and identities play in political decision making (Scharfbillig et al., 2021). The latest report on meaningful and ethical communication is currently in development, said Smillie.

The project on meaningful and ethical communication has several main components. The first is a thorough review of the science, and second is original research on the efficacy of framing with values. The third component is engagement with stakeholders, including front-line professional

communicators. Finally, the fourth piece is citizen engagement; meetings were held in nine member states to listen to citizens’ perspectives on the topic of meaningful and ethical communication. In addition to these reports, the European Commission has also created competence frameworks to help scientists and policy makers better understand each other, said Smillie. Specifically, Smart4Policy is an online self-reflection tool that allows people working in the science and policy fields to better understand themselves and each other.2

During discussion, Smillie explained that her previous experience in a European Union (EU) agency taught her that effective communication among countries with varying cultures and languages necessitates member states adapting everyday health messages to their own contexts. This requires humility, “staying out of the limelight,” and building strong relationships with key partners and stakeholders. Although some EU-wide messaging is designed to have a broader appeal, much of the agency’s work relied upon member states contextualizing messages for their particular cultures, said Smillie.

THE ROLE OF EMOTION

During discussion, one participant noted that many situations that require effective health communication—from pandemics to natural disasters—often involve heightened anxiety and emotions. Panelists offered their views on the role that emotion plays in health communication. Lupia responded that people generally think the “proper way” to interpret information is to think about it first and feel it later, but studies demonstrate that the opposite sequence more accurately describes typical information processing. This partially explains why building credibility is so critical to effective communication; without a relationship in which people want to hear from the communicator, the message will not get through. Once people are paying attention, said Lupia, scientists are ethically obligated to convey their knowledge in a transparent way, and to be clear about what they do not know, to avoid misleading people.

Lichtveld agreed that people tend to react emotionally first. She noted that, in her work on oil spills in the Gulf of Mexico, people’s worries about the health of their babies and the quality of the air were central drivers to her research, along with concerns about the physical impact of the spill. The job of a scientist, whether in public health or in a clinical setting, is to acknowledge and empathize with people and work with them to take action. Hallman added that “affect versus cognition” is an important issue in the field of risk communication. Authorities, including federal officials, often

___________________

think that if people “just understood the facts, everything would be fine.” However, sometimes people would prefer for authorities to simply acknowledge their anger and frustration, said Hallman. Once their emotions are acknowledged, a conversation about the situation becomes possible. Hallman shared that that reflecting compassion and empathy is often easier in a one-on-one interaction; it can “ring hollow” in a public relations campaign.

Smillie noted that the European Commission has been studying the potential use of various types of emotion in communication, and when emotion should or should not be used. The scientific literature, according to Smillie, shows that messaging that relies only on informing the target audience can have limited effectiveness. Successful persuasion requires authenticity and relatability, she said. She noted that while “persuasion” sometimes has a negative connotation, informing alone may be insufficient for helping people make good decisions. Lupia added that 90 percent of persuasion is listening to the target audience. If the speaker does not understand the audience and what motivates and concerns them, the message is unlikely to get through. Gardner acknowledged that while tailoring a message to a particular audience is the most effective approach, it can become challenging to do so if there are multiple, diverse audiences and a limited time to communicate the message.