Effective Health Communication Within the Current Information Environment and the Role of the Federal Government: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 6 Capacity: Organizational Capacities for Agility

6

Capacity: Organizational Capacities for Agility

Organizational structures and roles can facilitate agility in the federal government, which can be consequential for the timeliness and responsiveness of communication, as participants noted throughout the workshop. Remarks and discussion explored approaches for addressing barriers to nimble decision making and cross-agency coordination.

Donald Moynihan, Chair at the McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown University and Planning Committee Member, set the stage by explaining why agility in government can be so challenging. He explained that federal employees make up a smaller percentage of the population than in years past—they now represent about .64 percent of the population, whereas in the 1960s they represented about 1.1 percent—and that political appointees have been playing increasingly important roles, despite an average of only 18 months in office. In addition, government is often accused of being slow moving, said Moynihan, some of which is due to “procedural fetishism”—the idea that governments are attached to rules and processes rather than outcomes. In addition, the negativity bias explains why the public and politicians are more in tune with stories of failure than success; this natural bias generates incentives for blame avoidance and shifting, said Moynihan. Panelists offered their views on improving the way the government can function more effectively and how agility and innovation in government can help to improve health communication.

APPROACHES FOR INCREASING AGILITY IN GOVERNMENT

Agility requires an open mindset, or the ability to think about new things and changes, said G. Edward DeSeve, Coordinator of the Agile Government Center at the National Academy of Public Administration, which serves as the hub of a network that brings partners together to develop and disseminate agile government principles. DeSeve also drew on his experiences as Special Advisor to President Barack Obama, overseeing the successful implementation of the $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, and other roles he has held within government. An agile government is one that has the trust of its citizens—people believe that the government will be responsive to their needs and reliable in providing services. Trust in the government, said DeSeve, has real-world consequences; for example, research published in 2022 estimated that global deaths from COVID-19 could have been reduced by almost 13 percent if all nations had a high level of trust in government (COVID-19 National Preparedness Collaborators, 2022).

DeSeve shared the definition of trust in government from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD identified and defined five attributes that influence trust in government (Box 6-1).

Trust in government varies greatly around the world, said DeSeve. In the United States, trust in government has declined significantly over the last several decades. In the early 1960s, around 75 percent of people trusted the government to do what is right always or most of the time, but this number has since declined to around 20 percent. This erosion of trust, he said, leads

to people’s unwillingness to hear communication from the government. The level of trust is better at the state and local levels, with around 65 percent of people trusting state government and 75 percent of people trusting local government in 2013. DeSeve said, “the closer government gets to the people, the higher the degree of trust.”

Increasing trust is a core part of agile government, which DeSeve defined as a framework for developing and implementing policies, regulations, and programs at all levels of government to deliver transformational change by improving competence, respecting public values, and increasing trust. He suggested that these principles cultivate “a new mindset for government at all levels,” and his colleagues at the National Academy of Public Administration have defined a set of principles for agile government (Box 6-2).

DeSeve drew on his experience in the Obama administration to illustrate these principles. After the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was passed in 2009, DeSeve worked as a Special Advisor to the President to distribute nearly $800 billion. The first step, he said, was to create a series of networks. An internal network included 22 agencies, while external networks included financial officers in various jurisdictions, mayors, governors, and others. These networks worked together to focus on the mission to be accomplished. Each agency identified a single responsible individual who led a series of teams within the agency, and team members worked together in highly skilled, cross-function teams. Teams had to focus on their area—whether fixing roads, doing science, or building housing—but they also needed to think creatively and be open to change. Further, the White House set a goal of spending 80 percent of the funds within 18 months of the legislation’s passage, so the teams had to move quickly, be persistent, and be willing to change course. “If something did not work, we had to change our mind quickly and move onto something else,” said DeSeve.

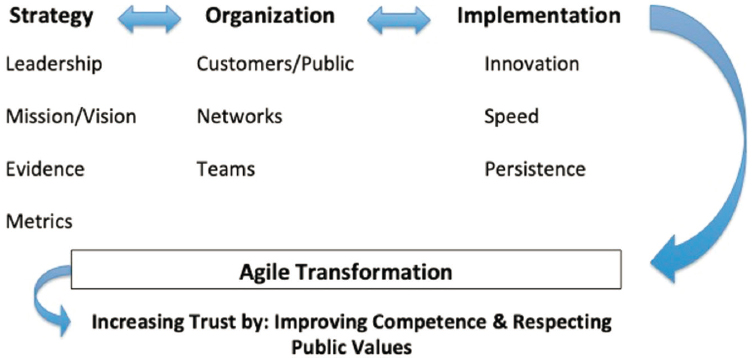

While each principle of agile government is important, said DeSeve, the key is an integrated framework. The government’s strategy, organization, and implementation need to be based on the principles and need to work together (Figure 6-1). Each principle relies and builds upon the others; leadership ensures a focus on the mission and the vision, evidence is gathered to create metrics, the customers and the public are involved in macronetworks and agencies to rapidly innovate implementation, and the process is continually iterated and refined over time to increase trust, improve competence, and respect public values.

SOURCE: Presentation by Edward DeSeve, March 21, 2023.

The framework and principles for agile government can be used within government agencies or efforts, including health communication. “There has to be a leadership group that is willing to articulate what success looks like. What does the mission and vision look like, what does evidence look like, and finally, how will we know if we have succeeded?” stated DeSeve. He offered the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs as an example of an agency that has made major improvements by practicing all the elements of the agile government framework.

Technology, communication, and workforce development are critical components of implementing the framework for agile government, said DeSeve. Technology allows for an exchange of information and enables interaction between the government and the public. Communication needs to be a two-way street, he said, and the government needs to be responsive to information from the public. To do so, the government workforce needs to be agile; this will require a significant amount of training at all levels, he said.

REFLECTIONS AND INSIGHTS FROM THE RESPONSE PANEL

Following DeSeve’s remarks, three response panelists and workshop participants discussed challenges and potential solutions for increasing agility in government to improve the effectiveness of federal health communication.

Joshua Sharfstein, Vice Dean for Public Health Practice and Community Engagement at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, spoke about his time as the Principal Deputy Commissioner of the

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the challenges he observed. One major challenge, said Sharfstein, is risk aversion. Trying to get something done in the federal government could be like trying to “tiptoe past 80 closed doors, and any one of them could spring open” with someone jumping out to stop it. There was a constant fear that something would go wrong, and this fear often persisted even after the action was complete. For example, when the FDA took action against caffeinated alcoholic beverages, Sharfstein described steps taken around the communication of this action, including engaging a democratic and republican State Attorney General, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). He also ensured a careful strategy with stories to share. It was “wildly successful,” explained Sharfstein, but after it was over, Sharfstein said, colleagues in the executive branch told him, “‘You have no idea how lucky you are that this did not go totally south’… everybody was still thinking about risk aversion.” One potential way to ameliorate the pervasiveness of risk aversion in government, he said, is to partner with or lean on others who are less risk averse. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Johns Hopkins University presented information about the pandemic in ways that “would have been hard for the CDC to do,” such as discussions about the implications of various policies.

Another challenge of communication in the federal government, said Sharfstein, is an emphasis on quality over speed. Although understandable, such emphasis can have unanticipated consequences. He shared an example from one of his first days at the FDA. In the face of a pistachio recall, Sharfstein wanted to get a press release out quickly. At the time, the process for press releases involved sequential editing by each person involved. After four hours, the document came to Sharfstein and, when he accepted all the changes, the press release “made absolutely no sense.” A new process was implemented in which everyone gathers in the same room and finalizes a message together. Sharfstein said that it is important to consider how communication processes balance the needs for speed, quantity, and quality.

A third challenge is that people in government feel “an awesome responsibility.” This sense of responsibility, he said, is certainly admirable. But sometimes government workers feel they cannot share that responsibility with others; they feel like they have to “sink or swim” on their own. Sharfstein relayed a story about when the FDA worked with the Consumer Product Safety Commission to take infant sleepers off the market. He suggested inviting the American Academy of Pediatrics to participate in the press conference, and some of his federal colleagues were very uncomfortable bringing in a voice from outside government. In the end, the outside group was successfully included, but some people felt like norms had been violated, he said.

Sharfstein noted that sharing responsibility is particularly important at times when government’s credibility is being attacked or questioned by a subset of the public. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was critical to have communication partners that could share the responsibility for key messages. Creating these partnerships requires transparency, trust, and information-sharing mechanisms, he said. Government agencies are not keen to share information and planned actions ahead of time, but effective partnerships require keeping one another in the loop. He gave the example of a state health official who lamented that she found out about FDA actions in the newspaper; when citizens came to her with questions and criticisms, she was not prepared to respond and it “undermined the whole credibility of the enterprise.” In the current information environment, communicating effectively with the public will require government willingness to share responsibility, lean on partners, and discover new paths, said Sharfstein.

Sharon Natanblut, Principal at Natanblut Strategies and Planning Committee Member, spoke to workshop participants about participating in agile government while working at the FDA. She described the impact of a leader with a strong vision and willingness to take some risks in the service of public health. These qualities were most evident, she said, in the decision for FDA to be involved in tobacco regulation, even though this authority was not explicitly granted by statute. A cross-cutting team of innovative thinkers with skillsets in law, science, and policy worked “day and night.” The existing leadership understood that messaging about policy is not something that only happens at the end of the process, said Natanblut. Instead, messaging around the harms of tobacco, especially to children, became part of all the FDA commissioner’s tobacco-related actions. Investments in communication technology during this time, said Natanblut, were also made in anticipation of the need for an updated system to manage public comment.

Natanblut also shared stories from her work at FDA after the Food Safety Modernization Act was passed and the FDA was given the responsibility of regulating farmers. The FDA had no previous working relationship with farmers, said Natanblut, and many farmers felt animosity toward the agency. Natanblut and her colleagues traveled across the country, visiting as many farms as possible. Interacting with the farmers, hearing from them directly, and letting them know that the agency cared “made all the difference.” Natanblut also worked on stakeholder engagement at the FDA; she noted that “real” stakeholder engagement means getting to know people and figuring out who is knowledgeable and influential. Engaging people before a particular policy is put forth often allows for the development of a better policy and can lead to better media coverage and better support.

This process is “not for the faint of heart,” she said, but it results in stronger policies that the public can support.

A third respondent, K. “Vish” Viswanath, Professor of Health Communication at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, suggested that agility means responsiveness to constant change, conflicts, controversies, and outcomes. In the context of health communication, how will campaigns and other planned or unplanned communication be responsive to feedback? Viswanath noted that DeSeve listed “speed” as one of the principles of agile government; he argued that it is not speed that matters, but rather timeliness. Building a feedback loop into a government intervention or communication is key to ensuring that feedback is received and used to adjust the intervention in a timely manner. This approach, said Viswanath, is part of the adaptive learning process.

The adaptive learning process, he explained, involves several steps. The first step is identifying the goal and the theory of change. Taking the time to do this step “forces people to really lay out what they are trying to accomplish and how they will do that,” explained Viswanath. Next, it is necessary to collect data and engage with stakeholders and communities. Viswanath stressed the importance of meeting not only with government and other high-level partners, but also with local leaders and program beneficiaries. Stakeholder and community engagement often results in modification of the goal or theory of change. In addition, once the communication or program has begun, it is critical to continue to meet with stakeholders and community members to reassess and reflect on what has worked and what has not, and to discuss changes to implement moving forward. Viswanath noted that many people in government already do such “after-action” reports, and that he utilizes them in his work in Nigeria as “pause-and-reflect” sessions. These sessions may include focus groups or other approaches for collecting feedback, and they make the system more agile, adaptive, and experimental. Building a feedback loop into the system ensures that course corrections are done in time to achieve the goal, said Viswanath.

In discussion, one participant added that the planning and feedback loop could benefit from tabletop activities that involve practicing how to collaborate, how to communicate, and how to make plans. In her experience, conducting such exercises has made certain fields more prepared for crises than communications and social and behavioral scientists often are.

DISCUSSION

Following the panelists’ responses, Moynihan opened the floor for a discussion among workshop participants and speakers. Panelists and speakers discuss (a) cross-sector collaboration, (b) the role of communication in decision making, and (c) the role of politics.

Cross-Sector Collaboration

During discussion, DeSeve agreed that cross-sector collaboration is essential for agility. For example, the National Institutes of Health was working with pharmaceutical companies and researchers long before Warp Speed (the initiative to develop a COVID-19 vaccine quickly) was implemented. Viswanath added that the success of Warp Speed was due in large part to decades of federal investment in the scientific enterprise, as well as to successful public-private partnerships. DeSeve said that government can act as a leader or convenor to bring sectors together, but other stakeholders need to be involved in planning long before implementation. Viswanath agreed, noting that diverse stakeholders see problems in unique ways, so involving them in planning provides a broader understanding of the issue and a better-defined goal and plan. Natanblut said that experts at an agency sometimes feel that they have all the knowledge they need, and they do not prioritize engaging with stakeholders. A program that is entirely invented and developed internally is highly unlikely to be successful, she said, but it can be challenging to convince agencies of this.

Sharfstein added that he supports external engagement, but he does not like the word “stakeholder” because it often refers to people who have a vested interest in something. In practice, the term “stakeholder” often gets defined as the regulated entity, to the exclusion of the public interest. Providing transparency around data and decision making is needed, but it is critical that “vested interests do not have a disproportionate influence on a process where there is a public good.”

The Role of Communication in Decision Making

Many participants noted that communication experts need to be involved when decisions are made. As an illustrative example, one participant stated that when her local health department wanted people to get vaccinated in 2021, it used a public relations approach focused on the use of technology. That is, “build the website, they will sign up.” Communication experts could have improved the strategy and enabled the health department to meet its goals more effectively and efficiently. However, she added, there is a lack of systematic data collection regarding communication capacities in public health. The lack of evidence makes it difficult to convince a health director that a team needs communication experts.

Sharfstein pushed back on the contention that communication needs to be involved from the very beginning, saying that decisions need to be made based on the right thing to do, and then communicated. Sharfstein noted that, in his work, he has seen problems arise when people are influenced by their perception of how a decision will be communicated, and this can circle back and affect decision making.

A participant challenged Sharfstein on his assertion and offered an example of why communication needs to be at the decision-making table. There is a vaccine delivery candidate in development that essentially consists of a bandage with a dissolving microneedle; this technology has a huge number of advantages, including not requiring a trained person to administer it. However, making a fully informed decision about whether and how to implement this type of technology requires an understanding of how the public might perceive it, and in particular, an understanding of misinformation narratives that exist around microchips and 5G technology. The role of communication experts is not simply to release information and “twist it this way or that.” Rather, they can provide an understanding of human behavior and feelings. This information needs to be available when a decision is made, he said.

Natanblut agreed that communication has an important role in the decision-making process. When health-related decisions are made, they can sometimes be difficult for people to understand or accept; communication experts can help people understand and trust the process and the data used to make the decision. However, if the communication experts were not present when the decision was made, they will lack the sufficient understanding of the process necessary to communicate with the public. Further, having communication experts present allows them the opportunity to raise questions and concerns to the subject matter experts, based on their understanding of how people think and behave, and to help ensure that scientists and leaders understand how their decisions might affect people “in the real world.” Sharfstein responded that he appreciated these points and agreed that the ultimate goal is to make a “decision that can be defended entirely on its merits” and can be very clearly communicated. Viswanath added that there are many types of communication experts and many areas of social science expertise (e.g., human behavior, public relations) that can contribute valuable insights as part of a team. One participant noted that the COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged reflection about how and where to incorporate communication experts and emphasized the need for communication expertise on leadership teams. This is a culture change that the CDC is committed to seeing through, she said.

Role of Politics

Members of Congress are like the board of directors for federal agencies, noted one participant. Data and health communication sciences are vitally important, but in the federal context, politics play a role in communication and decision making. A workshop participant agreed and added that the process of listening to the community about their perceptions, concerns, and information voids can be seen by some as creating “reputational risk” for the agency involved. A shift is needed, the participant added, to recognize that community engagement is part of the critical work of figuring out which programs and solutions are effective.