Effective Health Communication Within the Current Information Environment and the Role of the Federal Government: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 3 Capacity: Listening to and Engaging Communities

3

Capacity: Listening to and Engaging Communities

The capacity for listening to and engaging communities was a major focus of the workshop and was emphasized by many participants. Although government agencies face numerous challenges in connecting with and listening to communities, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented an opportunity to learn how to connect with communities and to rebuild trust, explained Amelie Ramirez, Professor and Chair of Population Health Sciences at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Director of Salud America!, Planning Committee Member, and moderator of a session focused on this topic. Speakers addressed principles and models for engaging communities that could be applied in the federal context.

PRINCIPLES FOR UNDERSTANDING COMMUNITIES

“When you have seen one community, you have seen one community,” said Al Richmond of Community-Campus Partnerships for Health. In health communication, there is often an inclination to lump people and communities into categories that may not be accurate or useful. For example, he said, many initiatives use the phrase “Black/African-American” to describe a community. However, these terms could be similar or mean something very different—a Black American could be someone born in Nigeria, or someone of Nigerian descent born in the United States, or someone whose family has lived in the United States for generations. The phrase “Latino/Hispanic” has the same issue—a Puerto Rican U.S. citizen may not be in the same community as a Dominican or a Cuban immigrant. It is important that health communicators take the time to understand the unique nature of the communities they are working with and use clear, accurate, descriptive terms. With the growing diversity in the United States, it is important to avoid assumptions about communities when planning health communication programs. For example, a person from Mexico may speak neither Spanish nor English. The “real work” in public health is often done “on the ground” through community organizations and relationships, said Richmond. His requirements for understanding a community are summarized in Box 3-1.

Richmond shared two examples of promising approaches for engaging communities, in keeping with these principles that could be applied in a federal context. The first, The Black Story Summit, a project funded by the National Network to Innovate for COVID-19 and Adult Vaccine Equity, produced documentaries to give people the opportunity to talk about the community work that was done “block to block” to save lives during the COVID-19 pandemic. This project, said Richmond, provides “the voice of the community in their own words.”

A second project, iHeard, works to combat the spread of public health misinformation. Several hundred community residents and leaders receive a text message each week asking what they have recently heard about COVID-19. The project curates a list of the top five topics reported that are circulating in the community and sends a text back with the correct information. Projects like this hold a lot of promise for addressing misinformation and effectively communicating accurate messages, said Richmond. The same type of platform could be used during crises like natural disasters, to learn what information people need and get that information to them.

COMMUNITY-ACADEMIC PARTNERSHIPS: LESSONS FROM FLINT, MICHIGAN

Flint, Michigan, was a city already in crisis in 2020, said Ella Greene-Moton, Administrator of the Community Based Organization Partners Community Ethics Review Board and Flint/Genesee Partnership, Health in Our Hands, and Planning Committee Member. The Flint water crisis had left residents feeling overloaded with information and communication, and trust in institutions was severely damaged, Greene-Moton said. However, Flint has a long history of community-academic partnerships, with relationships built on a foundation of trust, respect, and transparency.

Greene-Moton said that when the COVID-19 pandemic began, public health leaders were able to leverage these partnerships to pivot efforts toward communicating about the pandemic. “We realized that it would take a bidirectional process, realizing the importance of clarity even in word choice, using usage and definitions and in this case, a clear definition and understanding of communication, recognizing that a critical component of the communication process is the exchange between the academic partner and the community partner,” she said. She also shared that a community webinar transitioned to a focus on COVID-19. Greene-Moton said that this approach was effective because the community already trusted the

people involved and the credibility of the webinar series. She also noted her involvement with efforts to document the protocol to prepare for future crises. Finally, Green-Moton said:

I want to leave you with this thought: just because you are right does not mean the other person is wrong. As in this case, it only means that you are only looking at it from a totally different view. If we keep that in mind and even use that in practice, I think it will help us all grow as we are trying to communicate and connect with the communities that we are interested in working with.

CENTERING COMMUNITY: LESSONS FROM PUBLIC HEALTH — SEATTLE & KING COUNTY

“Community partnerships are one of the core values of our strategic plan,” said Khanh Ho of Public Health — Seattle & King County. Ho and her colleague, Emma Maceda-Maria, shared an example of their community partnerships work: a program called Fun to Catch, Toxic to Eat. This program, said Ho, is a partnership with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and was built with many community voices. It is a health-promotion program that educates local target audiences on healthy seafood consumption from the Lower Duwamish Waterway, a toxic and contaminated Superfund site. Instead of simply saying “do not eat the fish,” Public Health-Seattle and King County works with local subsistence fishing communities to better understand their culture and practices. The goal of the program is to encourage the target audience—which includes immigrant communities, refugee communities of color, fishing communities, and pregnant and nursing women—to make healthier choices. The health department began with “boots-on-the-ground community outreach,” said Ho, recognizing the expertise within the community, meeting with trusted messengers and influencers, and forming partnerships with stakeholders including decision makers and federal agency representatives. These stakeholders were willing to share knowledge and power with the community, she said.

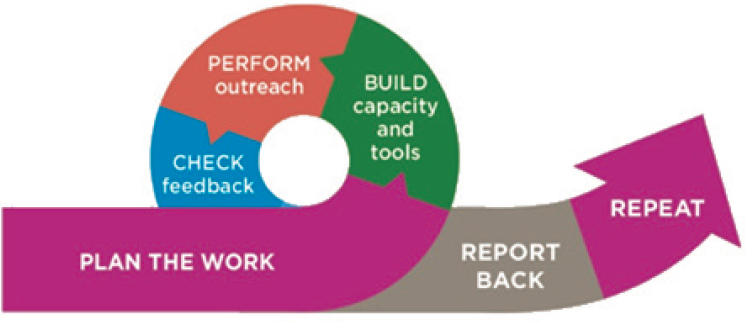

The program was built using a Community Informs All Stages approach, in which the community is “at the table” throughout the process (Figure 3-1). A community steering committee informs the planning. Community health workers get feedback from community members at every step, conduct community outreach, and develop culturally appropriate strategies and tools. The health department then revises and rethinks the plan based on community input and evaluation. The practice of engaging community members involves three core tenets, said Ho: capacity building, meaningful involvement, and empowerment. Community leaders representative of the target audiences are hired, trained, and meaningfully involved

SOURCE: Presentation by Khanh Ho, March 20, 2023.

in building education materials and health-promotion tools. Through their participation in this process, community leaders are empowered and can speak directly and transparently with institutional leaders. This process helps to address the power imbalance that often exists between “elites” and community members. Ho shared a quote from a community member involved in the program; he said, “They [public health department] have always included us in the process, they make us feel important, we are united, and it has always been that way. They ask us to be part of everything, every step, we are making history…Normally, a decision is made in an office and that is it, but not here.”

This type of community-based model has also been applied to other health department programs, including COVID-19 mitigation and response and climate health equity. It “takes a lot of creative thought and solution-forming flexibility,” said Ho, and requires “meeting folks where they are.”

Maceda-Maria spoke about the program from the perspective of a community leader. She and other community members went through the capacity-building program, and she later led the program with community partners. There is a lot of in-person, hands-on training that allows community leaders to practice sharing messages and getting feedback, she said. One community leader said, “We started with lack of knowledge and confidence, but throughout the training we gained more knowledge and also the community is more educated, so the conversation is getting easier and I am able to deliver the message as well as answer questions.”

The meaningful involvement of community leaders, said Maceda-Maria, enables engagement with agencies that want to break down barriers and have open, honest conversations with community members. Maceda-Maria was involved in co-creation of educational materials and tools, including

leading community outreach and creating a video directed at pregnant women. When Maceda-Maria began the program, she was nervous about talking to community members and sharing messages with them, but through the process, she gained a sense of empowerment and a boost in confidence.

Maceda-Maria explained that, following her training as a community leader, she used her experience in other capacities, including a Community Navigators Program for COVID-19 outreach. In this program, community leaders educated communities, conducted vaccine clinics, distributed personal protective equipment, and provided food to populations that were reluctant to leave their communities. In addition, Maceda-Maria used her experience in programs for wildfire health, recycling and waste management, and flood control. She noted that, in one program, the health department proposed a plan she felt would not work in her community; her empowerment enabled her to express her reservations and create her own proposal. Maceda-Maria said that this program has given her “a seat at the table” and the ability to elevate her community’s voice so that its needs are met. Maceda-Maria emphasized that underserved communities are eager for knowledge and desire to protect themselves, but that messages do not always resonate because of the way they are shared. “If government agencies collaborate with communities, communities will be heard and they will be able to take the steps to protect themselves,” she said.

FEDERALLY QUALIFIED COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS

Greg Talavera, Professor in the Department of Psychology at San Diego State University and Co-Director of the community-based South Bay Latino Research, told workshop participants about his experiences working with a community-based Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC). FQHCs serve as primary care providers for 30 million patients each year, most of whom have low incomes, are members of racial or ethnic minority groups, and are publicly insured or uninsured. FQHCs are a “great laboratory” for public health, communication, and community outreach, said Talavera. He shared details of a model that has been adapted for FQHCs, which demonstrates potential for collaboration between federal agencies and communities. The basis of the model is community-based participatory research (CBPR). CBPR can be used for many types of health-related efforts, said Talavera, ranging from service-oriented delivery programs to randomized clinical trials. CBPR involves collaboration between scientific researchers and community members to address diseases and conditions affecting the community. It recognizes the strength of each partner, and the community is involved as an equal partner with scientists. Community members collaborate on all aspects of the project, which may include a needs assessment, planning,

research intervention design, implementation, evaluation, and dissemination of community-level interventions.

Talavera noted that “a lot of lip service” is paid to community engagement in research, but in many cases a researcher only wants a community organization to do the recruiting, or the researcher may want access to data held by the organization. In contrast, Talavera said he always insisted upon open discussions of the proposed plan, involving both the researcher and community partners. Further, Talavera only participates in research that is mutually beneficial to the researcher and the community. He noted that some federal agencies require universities to share funding with community-based organizations, and some even require the community-based organization to be the prime contractor with a subcontract to the university. This could be a positive shift, he said.

Talavera noted that his experience is with FQHCs, but that the CBPR model could be used for any federal program. However, he emphasized that building the necessary capacity and preparing all partners to collaborate takes work. These types of health centers have the advantage of being trusted organizations for community members; he noted that “if you can provide an individual in that community with good, quality medical services, you have their trust.” Hard-to-reach populations can often be found in these centers, as they are specifically designed to serve the underserved community. When the COVID-19 pandemic began, people came “knocking on the door” of FQHCs to help distribute information to communities. At Talavera’s center, there was a staff of 40 that could be immediately deployed and was trained in research ethics, communication, and health education. His center is also involved in the All of Us1 research program; researchers reached out to other FQHCs to recruit hard-to-reach populations, and six centers have recruited 12,000 participants for the program. These centers are an “untapped resource” for collaboration among federal agencies, researchers, and communities, said Talavera. While there is a need to build more infrastructure and capacity in some of the smaller centers, FQHCs can reach disadvantaged populations and bring community-based programs to scale.

STRATEGIES FOR VIRTUAL STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT

Dmitry Khodyakov, Co-Director of the RAND Center for Qualitative and Mixed Methods, shared his experiences working on in-person and virtual community engagement, with communities defined by geographic location, demographic characteristics, and medical condition. One of Khodyakov’s first projects at RAND was aimed toward evaluating the

___________________

effectiveness of evidence-based interventions using community-based participatory research; it involved African American and Latino communities in Los Angeles. At the same time, RAND was looking at ways to modernize its approach to conducting expert panels, known as the Delphi method. The Delphi method is an approach to collecting expert opinions both anonymously and iteratively, with the goal of reaching consensus. It is commonly used, he said, to develop evidence in health services research. Khodyakov said that, while working on both projects, it occurred to him that a modified Delphi method could be used to virtually engage communities, particularly larger numbers of community members who may not be located in one place. For example, rare disease communities that are spread across the country may benefit from coming together virtually.

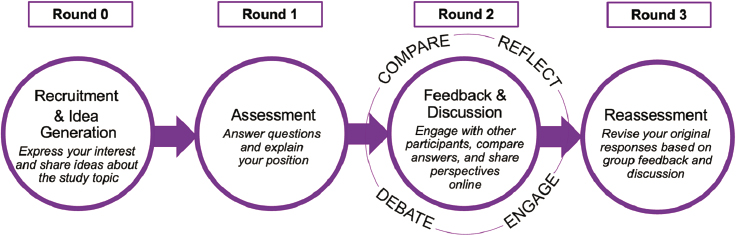

Khodyakov shared the modified-Delphi approach that was created at RAND for virtual engagement, called ExpertLens® (Figure 3-2). This method has been used in a number of studies and initiatives, he said, including the development of the National Suicide Prevention Research Strategy. The method is particularly useful for a multistakeholder engagement in which clinicians and patients are involved in the consensus process; the anonymity the method affords prevents power dynamics from affecting the outcome. The approach begins at Round 0, with recruitment and idea generation; a large number of participants are engaged and asked for input on the topic and the process. At Round 1, participants are asked a series of close-ended questions, and asked to explain why they chose their responses. At Round 2, each participant receives a report showing how their individual answers compare to those of other participants, and they are asked to share their perspectives on an online message board. This round includes opportunities for participants to compare, reflect, engage, and debate, said Khodyakov. Finally, in Round 3, participants reassess and revise their original responses based on the feedback and discussion from Round 2.

SOURCE: www.expertlens.org

Based on their experiences, RAND has developed 11 practical considerations for virtual, multistakeholder engagement (Box 3-2). These suggestions span three phases of research work: preparing for research, implementation and continuous engagement, and evaluation and dissemination.

DISCUSSION

Following the panelists’ remarks, Ramirez led a question-and-answer session among panelists and workshop participants.

Engendering Trust with Communities

The challenge of declining trust and polarization “is very real and is impacting public health,” said Richmond. Panelists addressed how the federal government, researchers, and other stakeholders can approach communities in ways that engender trust. Ideas surfaced by panelists are summarized in Box 3-3.

Need for Investments in Communities

Many participants expressed the importance of investing in communities and posed practical questions about steps that could be taken to advance these efforts. One participant asked panelists to share the biggest challenges they have faced in working with the federal or state government. Richmond noted that there is often “lip service” paid to equity and diversity, but not sufficient investment in the communities and the communication channels that serve them. For example, it is common for a government contract to be awarded to a top communication company, which then subcontracts out a small percentage to a newspaper or radio station that

serves a minority community. Richmond said that if the government does not invest more in these communication channels, they will not exist to help reach these communities.

Greene-Moton agreed that investment in communities is critical; she noted that communities often lack the capacity to act as partners for government initiatives due to limited investment in capacity building, although Talavera added that FQHCs are well positioned to work with federal partners. Maceda-Maria added that lack of accountability and sustainability is another challenge in working with the government. Government agencies approach communities with specific promises and needs but do not always follow through on the work. For example, community health workers were heavily leaned upon for COVID-19 response, but may now feel that they are no longer needed.

Several participants addressed the challenge of directly funding community organizations. Richmond noted that proposals are often geared toward academic or large-scale nongovernment entities. Waiting for federal funding can be another problem, said Ramirez. Funds can be slow to arrive, and community organizations often cannot wait as long for money as academic institutions or other partners can. Ho encouraged greater courage and creativity in finding ways to work with communities.

Participants also reflected on the impact that the end of COVID-19 pandemic funding will have on community engagement and communication work. Richmond noted that it is difficult for nonprofit organizations to build infrastructure when most of their funding is tied directly to a specific program: “when the program ends, the dollars end.” Investment in national infrastructure for community-based organizations is needed. Just as funds are needed to improve roads and bridges, he said, investment is needed in community health infrastructure, so it remains robust, strong, and vibrant for current health issues and future crises. Richmond said that funding for communication staff can be particularly difficult to come by. Some organizations “are so busy doing the work that they do not focus on communication,” while others are not sure where to find funding. Greene-Moton said that an organization she works with has identified some flexible funding to allow for building infrastructure and hiring a communication specialist, but funding remains a challenge. Ho said that in new initiatives such as the climate health equity response, King County has prioritized hiring a communication specialist as one of the first employees. Richmond noted the increasing importance of defining “community engagement,” as pharmaceutical companies and others may invoke this term to refer to engaging community organizations to recruit for clinical trials, which may be at odds with the educational mission of many organizations.

INSIGHTS FROM COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT BREAKOUT SESSIONS

On day two of the workshop, two small groups participated in separate facilitated discussions to generate ideas for building capacity related to listening to and engaging communities. Each group considered the same questions:

- What resources do we have inside or outside of government to address challenges to building capacity for community engagement?

- What are examples of successful efforts that could we learn from?

- What resources are most needed to make progress on this priority/challenge?

- Who else should be involved in addressing this challenge/priority?

Appendix C summarizes the ideas generated through these discussions, as reported by session facilitators Amelie Ramirez and Hilary Karasz.