Effective Health Communication Within the Current Information Environment and the Role of the Federal Government: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 5 Capacity: Expertise and Human Capital

5

Capacity: Expertise and Human Capital

Communication is a critical function of any effort to improve health and is most effective when it leverages expertise and human capital in communication and the social sciences, emphasized multiple speakers. Panelists and discussion addressed the near- and long-term steps toward ensuring that the federal government draws upon the expertise necessary to meet current and future health communication needs.

Effective health communication is vital for decision making, and it goes beyond simply translating science or explaining results at the end of a decision-making process, said William Hallman, Professor and Chair of the Department of Human Ecology at Rutgers University and Chair of the Planning Committee. Instead, expertise in risk communication, science communication, and health communication needs to be integrated throughout the process to better understand people’s concerns, questions, and perceptions of an issue. The expertise needed goes beyond public relations, especially to communicate effectively during a crisis. Hallman said that while expertise exists within agencies, there is a need to map where the expertise is located, which competencies are represented, and which communication skills are still needed. “We need leadership from above,” said Hallman, to integrate communication science into the everyday work of federal agencies, and to reorient thinking to emphasize that it is everyone’s job to think about effective communication. This workshop session, he said, was designed to explore approaches for building capacity and to examine the benefits and challenges of various capacity-building approaches, including ways that partnerships and collaborations can be leveraged.

EXPERTISE AND CAPACITIES NEEDED FOR EVERYDAY HEALTH COMMUNICATION

Health communication is a critical mission, and it requires investment in the necessary skills, teams, and supports for those teams to conduct this mission, according to Itzhak Yanovitzky, Professor of Communication and Public Health at Rutgers University. Yanovitzky focused his remarks on ongoing, systemic efforts to communicate with the public and other stakeholders about health.

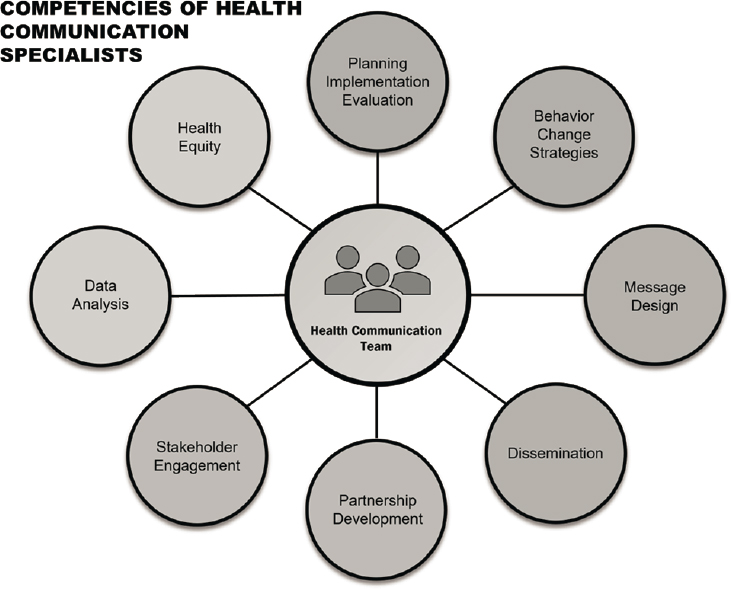

Yanovitzky described the numerous critical competencies and functions of health communication specialists (Figure 5-1), noting that there is no “one person unicorn” that can do all these things; instead, it requires a

SOURCE: Presentation by Itzhak Yanovitzky, March 21, 2023.

team with complementary expertise. For example, not every communication specialist needs to be a data expert, but every communication team needs a data scientist.

On the most basic level, health communication specialists use behavioral change theories to promote healthy behavior in a target audience. Message design is a major component of health communication; messages may be designed to convey information, to warn people of a risk, to encourage a behavior, or to remind people to take an action. There is a science to message design, said Yanovitzky, that offers a systematic way of thinking about the goals and audiences of the communication. Systematic tools such as problem analysis, audience analysis, and messaging testing are utilized to create an effective message and minimize unintended effects. Traditionally, dissemination has been a major focus of health communication, but specialists are also expected to engage in planning, implementation, and evaluation of health communication programs. According to Yanovitzky, this requires skills such as data analysis, stakeholder engagement, and

partnership development. In addition, specialists need to understand issues of health equity and remain conscious of equity in all communication efforts.

Yanovitzky emphasized that listening is a very important part of communication, particularly listening to what the listener may not “want to listen to.” He gave the example of town halls that he and his colleagues held about the opioid epidemic. The intended focus of these meetings was to talk about prevention, but community members wanted to talk about treatment. This indicated a need for increased focus on community priorities, he noted. Health communication experts can help decision makers see the value in listening and can help to create structural opportunities for listening. Yanovitzky added that “providing more science and more facts” will not be effective in the absence of underlying relationships. “Sometimes we think we have a communication problem, but we have a relationship problem instead,” he said. With a relationship in place, an agency can ask communities what they need. Many communities may need information about the types of resources that are available to them, said Yanovitzky.

In recent years, the federal government has invested much effort toward building capacity for systematic evaluation; the same kind of effort could be invested for communication. Yanovitzky shared a list of communication capacities, divided into three domains: professionalization, expert and technical support, and coordination and outreach support (Box 5-1). Communications is a unique field, he said, in that there is no standard training and people come into the field from multiple backgrounds. Developing standards for the field and creating clear career paths for people to follow would be useful, according to Yanovitzky. Communication specialists’ professional development could be enhanced through links with professional associations and by creating communities of practice. Helping people establish careers in government health communication could be one strategy for minimizing attrition, he added. Yanovitzky noted that health communication specialists are not experts in a particular area of health, but work across many areas and need a community of practice to collaborate and learn from colleagues. For communication specialists to be effective, he said, they need expert and technical support, including access to data, relevant audience/market research, and a platform for testing messages. Further, communication specialists need institutionalized access to experts—both from the health field and from communities—and they need the ability to work with a creative design team to produce accessible, actionable products. By collaborating with experts, communities, and designers, communication teams can create useful, effective products, such as interactive dashboards. Yanovitzky stressed the importance of creating products and materials that have a clear purpose and are actionable. Yanovitzky also noted that the National Institutes of Health has the opportunity to improve

communication capacity through its funding requirements. “Communication is a core function” of health, said Yanovitzky, and there is a need to learn more about where and how communication is most effective. Funding requirements could ensure that communication strategies are tracked and evaluated.

CAPACITIES NEEDED FOR EFFECTIVE HEALTH COMMUNICATION IN EMERGENCIES

The past three years of the COVID-19 pandemic have demonstrated that the federal government has enormous capacities but also serious constraints on its ability to communicate effectively with different populations, said Sandra Quinn, Professor and Chair of the Department of Family Science and Senior Associate Director of the Maryland Center for Health Equity, School of Public Health at the University of Maryland. The federal government can convene, provide information, build knowledge, and provide resources. However, the federal government has less capacity or ability to take the type of “hyper-local approach” needed both during a crisis and

in addressing chronic disease and health disparities, said Quinn. This is where state, local, tribal, and territorial health departments can build on the capacity of the federal government and translate those capacities into effective approaches for their communities. She emphasized several important capacities needed at the federal level for effective health communication in an emergency, which emerged from an earlier National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine workshop entitled Building Trust in Public Health Preparedness and Response Research (Box 5-2).

One particularly important capacity, said Quinn, is developing and sustaining community engagement and partnerships. Drawing on insights from the CommuniVax Study in multiple sites around the country, she emphasized that recruiting, training, supporting, and utilizing community health workers is vital. These workers can help to determine culture, channels, information needs, and potential messages for effective communication,

and can help to build trust between the community and the government. Sustained funding sources for community health workers, beyond grants that may “be here today and gone tomorrow” are critical, she said.

Quinn gave an example of the helpfulness of community health workers in working with communities. She and her colleagues have worked with local barbershops for over 10 years, and during the COVID-19 pandemic, a flyer with a lot of misinformation was left in the door of one of the barbershops. One of the barbers, a community health worker, brought the flyer to Quinn and her colleagues; this initiated an ongoing conversation, including town halls in which policy makers, scientists, community members, and other stakeholders were able to listen and communicate with equal voices.

To build capacity on the local and state level, Quinn emphasized that major long-term investments are needed. State and local health departments have shared that their capacity for community engagement and communication was limited before the COVID-19 pandemic and has since worsened. However, Quinn suggested several ways that the federal government could help improve engagement and communication capacity at the local level:

- Fund public health traineeships;

- Fund pre- and postdoctoral fellowships in key areas such as health communication, health literacy, social media, and countering mis/disinformation; and

- Fund pre- and postdoctoral fellowships in public health preparedness and response research and translation.

In discussion, to illustrate this point, Ella Greene-Moton, Administrator of the Community Based Organization Partners Community Ethics Review Board and Flint/Genesee Partnership, Health in Our Hands, and Planning Committee Member, noted that in Flint, Michigan, the COVID-19 messages coming from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were not trusted by the community. Green-Moton and her colleagues created a task force that included academics, the health department, grassroots organizers, and community- and faith-based organizations; this task force translated CDC messages into community messages that were often delivered in person. When citizens saw that trusted community members were giving the same information as the CDC, “they started to relax a little bit.”

Quinn shared that the same sort of community engagement process used with other communities can work with politically conservative communities. She and another participant both noted that evidence supports finding spokespeople who have a common identity with those communities with which they are communicating. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Francis Collins—head of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)

and an evangelical Christian—spoke on Fox News and in faith-based communities.

ENGAGING AND HONORING THE EXPERTISE OF NATIVE POPULATIONS

Native people have been communicating about health and science for generations, in an effective and culturally appropriate manner, said Amanda Boyd, Associate Professor of Health, Risk and Science Communication at Washington State University, member of the Métis Nation and Co-Director of IREACH, the Institute for Research and Education to Advance Community Health, which works with approximately 150 tribes and Native organizations around the country. Building capacity for health communication in Native communities begins with honoring the experience, expertise, and Indigenous knowledge that exists, she said. Boyd also emphasized that Native communities do not encompass only people living on reservations; over 70 percent of Native people live in urban areas. There are fewer data on these populations and often fewer formal care structures, but engagement can happen through cultural centers, clubs, urban health care organizations, and other mechanisms.

Research on health communication shows that one of the most common factors in effective communication strategies is the leadership and engagement of the affected community, according to Boyd. When the community leads or is involved, messaging is more likely to be trusted, barriers are more likely to be understood, and cultural and traditional norms can be incorporated into communication. Outside agencies or researchers may not have access to local knowledge, understand what affected parties care about, or be aware of the behaviors that affect exposure to a hazard. Boyd shared an example of the importance of this cultural knowledge. In Native communities, vaccine campaigns focused on getting vaccinated for one’s community, one’s relatives, and one’s elders. “The director of the CDC could probably not say that in a way that is appropriate and as effective” as tribal leaders could, she said. She also noted that some tribes have taken it upon themselves to use information from federal agencies to develop ways to engage their communities, noting that this adaptive work does not always have to happen within government agencies.

It is important to determine the best ways to connect Indigenous communities with federal agencies, noted Boyd. She stated that a benefit of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a greater understanding of the need to work with communities, and a greater interest in funding these initiatives. For example, funding from NIH’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics program enabled Boyd and her colleagues to work with five urban Indian health organizations to understand communication needs and perceptions of COVID-19 vaccines.

Boyd encouraged participants to continue to learn from the successes and challenges seen over the last several years, and to continue to fund community-based initiatives. Specifically, she said, there is a need for communities to co-create communication and engagement strategies. Rather than simply bringing information from the community to the decision-making table, community members need to be making decisions and co-creating strategies from the beginning of the process. Boyd shared an example from the Nez Perce tribe located in north-central Idaho. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the tribe had its own communication task force that met regularly to look at CDC guidance and communication and to determine how to amplify the information through their own networks. Boyd noted that the federal government was not involved in this effort, but the effort demonstrates the potential and expertise that exists within communities and could be leveraged by the government.

Boyd said there are many capacities needed for the government and Native communities to successfully collaborate on health communication, and two of those that she considers most important are summarized in Box 5-3.

CAPACITIES FOR EFFECTIVELY ENGAGING THE NEWS MEDIA

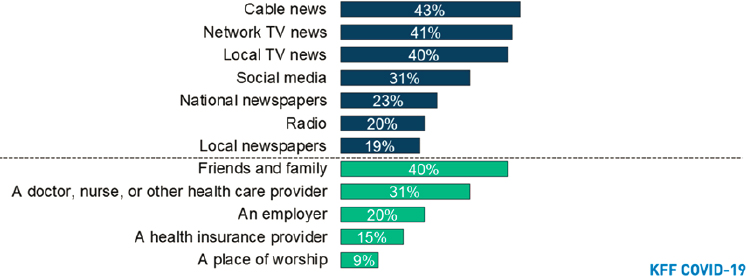

Americans rely on news media for much of their health information, said Sarah Gollust, Associate Professor in the Division of Health Policy and

Management at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health. Over the last several years, cable news, network TV news, and local TV news were particularly important sources of information about the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 5-2). Thus, for effective health communication, expertise in engaging with these media sources is key, as is access to the evidence needed to inform those engagements, she said. Gollust discussed the implications of several research findings for federal health communication:

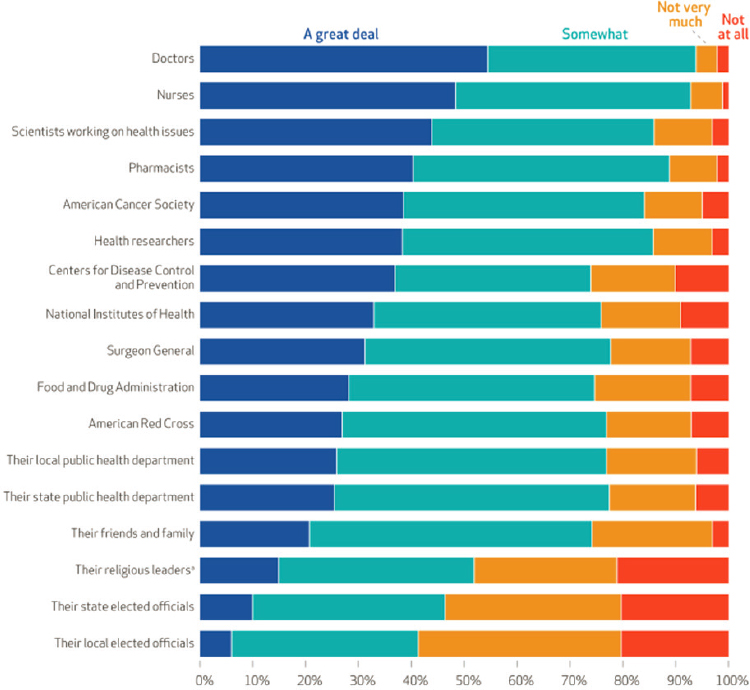

The first challenge, said Gollust, is a disconnect between the experts who are featured as information sources in the media and the degree to which the public trusts them. Studies show that politicians are the most cited source in television news. However, a 2022 survey of U.S. adults (SteelFisher et al., 2023) showed that politicians rank near the bottom of the list of sources trusted by the public. State and local elected officials were also near the bottom, with doctors, nurses, and scientists at the top (Figure 5-3). When politicians are cited in news coverage as a major source of health information, this can potentially exacerbate politicization of health issues and increase political polarization. Gollust suggested mitigating this problem by building relationships with a wider network of people who can serve as news media sources.

Expertise and capacity are also needed to navigate scientific uncertainty and to clearly communicate about such uncertainty with news media, said Gollust. The appearance of “conflicting science” through news coverage of the latest study or latest recommendation contributes to a sense among the public that science is “flip-flopping.” A related issue, she said, is a concern around inconsistent messaging, misinformation, and information overload.

NOTE: Percents represent those who reported getting at least a fair amount of information about the COVID-19 vaccine from each source over the past few weeks. Dark blue bars represent media sources of information and green bars represent personal sources of information.

SOURCE: Hamel et al. (2021).

NOTE: Weighted percentages are displayed. Survey question: “In terms of recommendations made to improve health in general, how much do you trust the recommendations of each of the following groups?”

SOURCE: SteelFisher et al., 2023.

Health communicators can engage with journalists early in the process of reporting, to help them understand the process of scientific discovery and evolution so that they can put new information in context.

Finally, when news media discuss health equity and disparities, said Gollust, they tend to use statistics or examples that focus on particular individuals, rather than emphasizing the structural and systemic reasons behind the disparities. Research shows that this type of coverage can invite a stereotypical understanding of the reasons for health differences between groups, rather than a fuller, more complete structural understanding. Again, health communicators can help by engaging early and often and helping journalists understand the structural issues, said Gollust.

EXPERTISE AND HUMAN CAPITAL NEEDED FOR EFFECTIVE LARGE-SCALE HEALTH COMMUNICATION CAMPAIGNS

Substantial, large-scale public health campaigns have different challenges than community-level campaigns, explained Robert Hornik, Professor of Communication and Health Policy, Emeritus, at the Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania. These large-scale campaigns need to communicate successfully with multiple communities, often without addressing the differences among them. In addition, most large-scale public health communication campaigns designed to change behavior ultimately fail. This does not mean that behavior change does not occur, he clarified, but that behavior change is not the result of one campaign. Instead, change is more likely the result of repeated exposures to messages in the public communication environment. For example, tobacco use has declined significantly over the last several decades, and condom use increased significantly during the HIV epidemic, but neither of these changes can be attributed to one campaign. Hornik said that the lack of “success” of any one campaign should not dissuade future campaigns, but emphasized that “this is hard work.”

Hornik reviewed three challenges of public health campaigns: models of behavior change, assuring exposure, and the capacity to adapt to new information. Understanding models of behavior change is an integral part of a campaign, he said. Once the target behavior for a campaign is chosen, the question becomes, “Why do some people engage in a behavior and others do not?” What alternative explanations might account for differences between those who change a behavior and those who do not, and what are the influences on behavior? There may be individual, social, or institutional explanations for behavior, said Hornik. For example, an individual may make a decision about vaccines based on personal beliefs about self-protection, about protecting others, or about possible side effects. Knowledge that other people are getting the vaccine—or not getting it—is a potential social explanation for behavior. Institutional explanations, such as workplace vaccine requirements, may be another reason for a person’s vaccine choice. To promote behavior change, communication campaigns could be directed at any or all of these areas.

The question, said Hornik, is to determine empirically which of these explanations matter, and for whom. For example, a campaign to educate people on the risks of cigarette smoking is unlikely to be effective, as nearly everyone already knows and believes that cigarette smoking is harmful. More effective messages might be that quitting smoking can save a person a lot of money, or that it is easier to quit if you quit with help. Hornik said that both of these messages have been shown to be predictors of whether people intended to quit smoking, but the first was more influential for men and the second was influential for everyone. While it is necessary to research

subpopulations and which messages work for each, “you cannot do 20 campaigns on a national level.” With limited resources, finding a common denominator among subgroups is a way to tailor a message to reach as many people as possible.

A second challenge for large-scale public health campaigns is developing an exposure strategy to ensure that the target audience is exposed to the message often enough for it to be effective. Hornik said that he has often seen the government develop a great messaging strategy but without an adequate exposure strategy. An exposure strategy takes into account the target population, what proportion of the population the message needs to reach, how many times individuals need to be exposed to the message over a given time period, and how exposure will be accomplished. Relying on social media or a website is “tempting” but not particularly effective. Hornik said that, in his opinion, a lack of continuous exposure over time is the single best explanation for the ineffectiveness of health communication programs.

The third challenge for campaigns is the need to be flexible and adapt when necessary. “A campaign is not a pill reflecting a fixed regimen that you are delivering,” Hornik said. It needs to evolve and adapt over time, whether because the population is changing or simply to correct mistakes made during development. Public health campaigns need the research capacity to feed information from the field back into planning and operations on an ongoing basis, and the operational capacity to adapt when changes are required. Systems need to be structured to collect evidence and use this evidence to improve.

Hornik closed by reiterating three key capacities for large-scale public health campaigns: (a) generate alternative possible models of behavior change and gather evidence for choosing among them; (b) assure adequate exposure to reach the audience, with enough frequency over time; and (c) adapt operations in response to ongoing evidence. Hallman added to this discussion by noting that the ability to document what has worked and what has not worked is another important capacity of large-scale public health campaigns. He noted that federal workers are often overburdened, particularly during a crisis, and lack the capacity to capture successes and failures as they occur; there are opportunities, however, to utilize students or fellows to track the day-to-day operations and add to institutional knowledge.

DISCUSSION

Given the importance of communication science, one participant asked how an “appreciation of communication science expertise among management and leadership” can be increased. Several participants noted that there

is a great deal of expertise within federal agencies, but a lack of awareness and appreciation of this expertise and what the work involves. Another participant noted that the phrase “health communication science” can confuse people, because there are so many aspects to communication and so many unique competencies. She wondered if speaking more specifically about what communication science entails could help improve understanding and appreciation of the role of these experts. Another participant added that, in addition to being specific about competencies, it is important to realize that competencies evolve over time. One participant noted that work is under way at the CDC to review the existing and needed competencies.

INSIGHTS FROM COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT BREAKOUT SESSIONS

On day two of the workshop, two small groups participated in separate facilitated discussions to generate ideas for building capacity related to expertise and human capital to support evaluation of federal health communication. Each group considered the same questions:

- What resources do we have inside or outside of government to address challenges to building the capacity for evaluation of federal health communication?

- What are examples of successful efforts that could we learn from?

- What resources are most needed to make progress on this priority/challenge?

- Who else should be involved in addressing this challenge/priority?

Appendix E provides a summary of the ideas generated through these discussions, as reported by session facilitators Jeff Niederdeppe and Itzhak Yanovitzky.