Effective Health Communication Within the Current Information Environment and the Role of the Federal Government: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 2 Key Cross-Cutting Challenges and the Implications for Federal Health Communication

2

Key Cross-Cutting Challenges and the Implications for Federal Health Communication

Key challenges to effectively communicating about health in the federal context include (a) declining social and institutional trust; (b) a competitive, complex, and rapidly changing communication environment; (c) increased political polarization of health and science; and (d) widespread health and communication inequities, said Jeff Niederdeppe, Professor of Communication at Cornell University and member of the planning committee. Some of these challenges have emerged gradually over time, while others have accelerated rapidly in recent years, he added. Niederdeppe moderated a workshop session focused on these challenges and potential solutions.

THE CHALLENGE OF DECLINING TRUST IN INSTITUTIONS

Confidence and trust are essential to the legitimacy of institutions and their ability to operate effectively, and people’s confidence in institutions, including governing bodies, businesses, churches, scientists, higher education, and police, has been declining in recent decades, said Henry Brady, Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the University of California at Berkeley. Citing data from Blendon and Benson (2022), he noted that during the COVID-19 pandemic, distrust in institutions was related to higher rates of COVID-19 infection, lower support for mitigation policies, and lower vaccination rates. According to Brady, in 2021, the top three reasons that people gave for not getting vaccinated involved mistrust of institutions: “see what happens” (58%), “distrust government” (37%), and “distrust scientists and companies” (28%). Successful health communication requires public confidence in institutions and trust in the information they provide, said Brady.

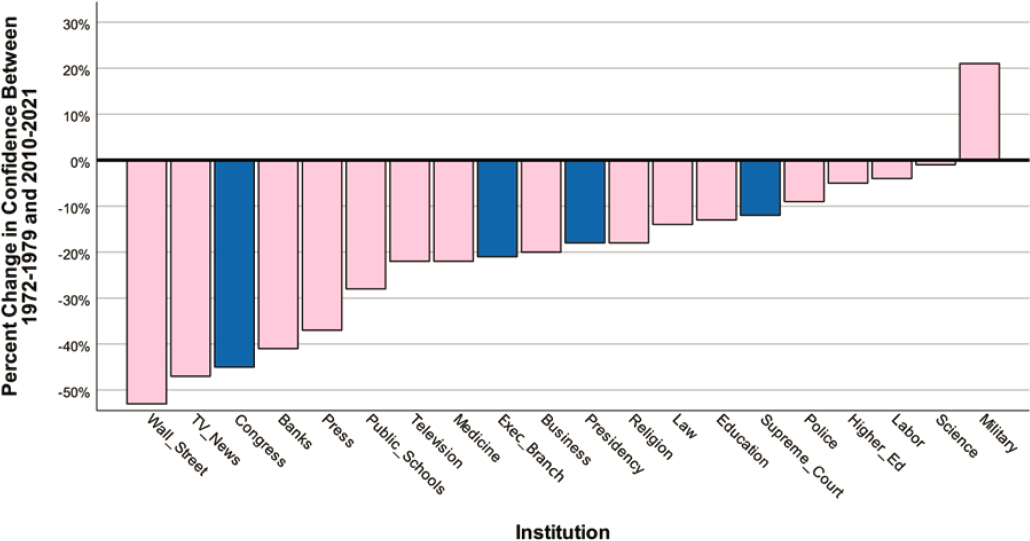

Brady shared his research findings on how confidence in various institutions has changed over the last 50 years. He and his colleagues used data from polls and surveys that asked people about their confidence in U.S. institutions, and they created a four-point scale, in which zero represented “hardly any confidence” and three represented “a great deal of confidence.” These data show the declining trust in every institution except for the military. Figure 2-1 illustrates these data, with branches of government depicted in blue.

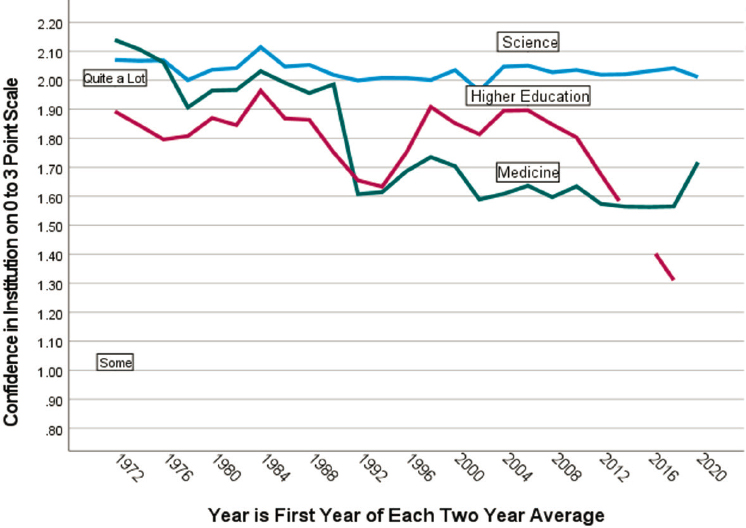

Despite these trends, confidence in science has been fairly stable, with only a very small decline over time. However, trust in institutions of higher education has seen a precipitous drop in recent years, while confidence in medicine declined in the mid-1990s but may be leveling out (Figure 2-2).

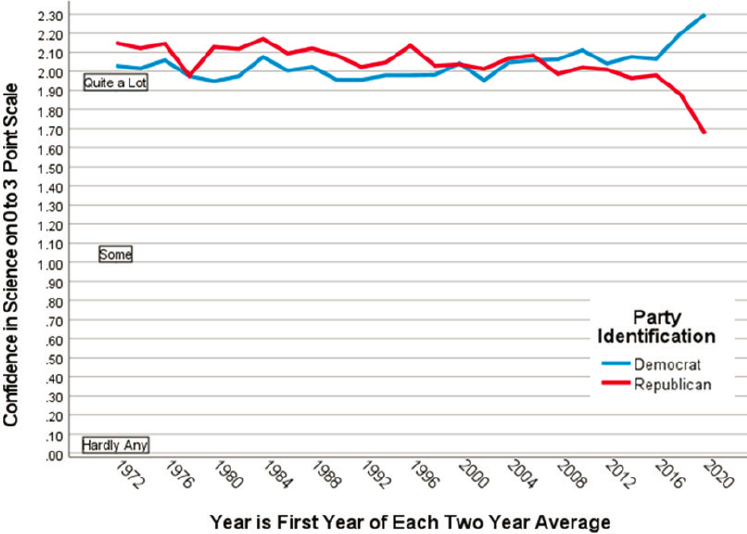

The bigger problem, said Brady, is that confidence in institutions has become politicized. In the 1970s, Republicans and Democrats had about the same level of trust in most institutions, with the exceptions of labor unions, which Democrats trusted more, and business institutions, which Republicans trusted more. By the 2010s, the confidence level in nearly every institution became polarized by party, with Democrats reporting more confidence in knowledge-producing institutions—the press, TV news, television, law, education, public schools, higher education, and science—and Republicans reporting more confidence in norm-enforcing institutions—religion, police, and the military. Republicans’ and Democrats’ levels of confidence in medicine and science have remained similar over time, but recent trends suggest that they are starting to diverge, as shown in Figure 2-3. This means, said Brady, that societal debates that occur about the police and the press are “going to come to the institutions that you deal with on an everyday basis.”

NOTE: Blue bars indicate political institutions and pink bars indicate nonpolitical institutions.

SOURCE: Brady and Kent, 2022.

SOURCE: Presentation by Henry Brady, March 20, 2023.

Brady offered several possible explanations for the decline in confidence in institutions over time and why confidence has diverged based on political affiliation. Some of the decline in confidence in certain institutions is related to specific events, such as scandals, bank failures, police behavior, and changes in press coverage, while some of the decline is due to generalized distrust in institutions fueled by Watergate and other large-scale events. Political polarization, said Brady, reflects that social, cultural, and racial issues in the United States are a new dimension of American politics. Institutions that produce knowledge or enforce norms are implicated in the polarization process. The individuals involved in such institutions have also become more homogenously associated with a particular political party. For example, professionals in the press, public schools, and higher education are more likely to be associated with Democrats, whereas professionals in religion, the military, and the police are more likely associated with Republicans, he said.

Brady described conclusions and suggestions from “Trust in Medicine, the Health System & Public Health” (Blendon & Benson, 2022), in which the authors offer several approaches for improving public confidence and trust. First, although trust in the institutions of medicine and health has declined over time, trust in nurses and doctors has remained high—85 percent of people report that they trust nurses “somewhat” or “completely,”

SOURCE: Presentation by Henry Brady, March 20, 2023.

with 84 percent saying the same of doctors. Brady said this shows that “the personal touch matters.” Citing Blendon and Benson (2022) and Hatton et al. (2022), Brady provided his ideas for how federal health communicators could increase public confidence and trust in public health communication (Box 2-1).

TABLE 2-1 Potential Solutions for Restoring Trust in Government

| Source of Legitimacy or Trust | Basic Mechanism | Problems | Examples of Problems | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory endorsement by government | Borrows legitimacy from government | Government may not be trusted or legitimate | Government not seen as legitimate; too “far away”; not responsive | Use local governments or non-profits |

| Effectiveness and efficiency in providing goods or services | Produces utility for individuals in good and useful products | Goods or services may be poorly provided | Products are shoddy; services are delivered poorly; quality of service is poor; long waits; too costly | Produce better products; perform better |

| Adherence to Ethical and Normative Standards of Society | Thought to be fair within the existing rules of the game | Violation of normative standards | Requiring bribes; getting kickbacks; acting immorally; harassing work culture; large profits or compensation | Avoid unethical behavior and be transparent about eliminating it |

| Culturally appropriate and acceptable | Appeals to basic cultural worldview | Lack of understanding of culture and subcultures | Selling culturally inappropriate products to children; Not understanding personal “safety”; Not understanding need for personal autonomy | Understand different cultures in the population and relate to them |

SOURCE: Presentation by Henry Brady, March 20, 2023.

Brady summarized his suggestions for rebuilding trust in institutions in Table 2-1. He also noted that highly educated “elites” often stumble in understanding and engaging with other communities, including conservative and minority communities. “We have met the enemy and they are us: elite, highly educated people who are not trusted by a large segment of Americans. And that is the problem we are facing, and that is a very deep problem,” he said. The answer to increasing trust in institutions is not “gimmicks”; rather, it is doing the hard work to gain a deep understanding of communities and the cultural differences among them, said Brady.

CHALLENGES OF THE COMPLEX HEALTH COMMUNICATION ENVIRONMENT

The health communication ecosystem has grown and changed rapidly, said Andy King, Associate Professor of Communication at the University of Utah, which makes reaching intended audiences and addressing complex public health problems increasingly challenging. The health communication ecosystem includes both the public communication environment (e.g., traditional media, online sources, public service announcements) and the nonpublic communication environment (e.g., private communication and information shared in a network of family and friends but not publicly available). Today, there are more communication platforms and user-generated content than ever before, said King. There is an almost-unlimited number of people to listen to, on platforms from YouTube to television news to government. Information can be conflicting and competing, whether in the form of misinformation about scientific findings or new government recommendations that differ from previous recommendations. Commercial interests also impact the communication environment, through direct-to-consumer advertising, predatory marketing, and promotion of expensive unproven treatments. Moreover, people experience the health communication ecosystem differently due to factors including racism and discrimination, social and digital inequality, and differences in communication infrastructure, he said.

When searching for health information, people often turn to the internet, said King, including federal agency sites, health news sites, general news sites, social media platforms, and more. In addition, people can actively look for health information or simply encounter it while scanning websites. Social media sites have proliferated in the past decade, and the presence and engagement of authoritative sources on these sites varies dramatically. Consumers are oversaturated with content and platform options. In the wake of COVID-19, there is both fatigue and exhaustion about health messages and a deluge of dis/misinformation on many health topics. Erosion of trust in institutions and the politicization of trust have further complicated the health

communication ecosystem, making it more difficult for people to find useful information, King explained. He suggested improving both communication infrastructure and communication strategies, as summarized in Box 2-2.

During discussion, one participant noted that much of the conversation around health communication centers on conveying accurate information, so that people can make good decisions. However, given the vast amount of information and diverse sources that exist, perhaps health communication needs a greater focus on helping people navigate the information environment. King responded that building capacities and providing tools for digital literacy, numeracy, and health literacy are very important, although these actions can be hard to implement widely. He emphasized, however, that there is still a need to provide accurate information and content that resonates with people. K. “Vish” Viswanath, Professor of Health Communication at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, added that “people are very smart,” and can think deeply about many topics. The issue, he said, is understanding how to tap into these strengths and reach people with health messages. Niederdeppe said that, within the health communication environment, many messengers do not have health and well-being as their goal but are instead focused on profit or power. In addition to improving health literacy and providing accurate information, there is a need to address the issue of industry and political influence, he said.

Competing in the information marketplace is a challenge for federal health communication, particularly when it is competing with misinformation and profit-driven media, noted one participant. Even with a large budget for a COVID-19 public education campaign, she said, it was difficult to get accurate messages to the public. However, another participant said that the government has some advantages on the internet. For example, government websites usually appear near the top of search results. Many

platforms have policies and algorithms that privilege credible sources from the government over other sources, he said. However, to compete, the government needs to create content in all relevant areas of the internet. For example, if a government agency is not engaged in a new platform, searches on that platform will necessarily result in nongovernment information. In addition, searches for information like unsubstantiated miracle cures are unlikely to result in credible government sources because the government provides no information about such topics. In general, the internet privileges credible government sources, he said, but the government needs to know where people are looking for information and be willing to create content to fill the gaps.

POLITICAL POLARIZATION OF HEALTH AND SCIENCE

Bruce Hardy, Associate Professor of Communication and Social Influence at Temple University, described the challenges posed by the political polarization of health and science and potential solutions for mitigating these challenges. Over the last several decades, said Hardy, disdain for members of the opposing political party has risen steadily. He noted that three foundational theories of human behavior offer new ways of thinking about this challenge: social identity theory, attitude consistency, and identity protective cognition.

According to Hardy, social identity theory (Tajfel et al., 1997) posits that communities can self-identify as belonging to a specific category, and compare and contrast their communities with others, reinforcing their own social identities. This theory emphasizes that people’s identities are based not just on who they are, but on who they are not.

Attitude consistency theory (Heider, 1946) suggests that if a person’s attitude toward an object is positive, and that object and a variable have a positive association, the person’s attitude toward the variable is also likely to be positive, explained Hardy. For example, if a person likes an athlete and that athlete is sponsored by a specific brand, the person is likely to have a positive attitude toward that brand. The same relationship also works in reverse, with a negative attitude toward an object engendering a negative attitude toward the variable. This theory is particularly salient in today’s health communication environment, said Hardy, because political identity can influence how receptive a person is to messaging from a particular federal agency. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Democrats have become more trusting of agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health, while Republicans have become less trusting of these agencies (Levendusky et al., 2023).

Identity protective cognition (Kahan et al., 2007), said Hardy, is the idea that people reject information, evidence, and messages that threaten

their identities and challenge their attitude consistency. Hardy et al. (forthcoming) have examined how this process may relate to science and public health becoming “issues” that are closely aligned with one party. Democrats are seen as caring more about science and being more capable of dealing with science-related issues, said Hardy, although when science is broken down into distinct areas, the advantage splits. Republicans are seen as having the advantage in nuclear science, military science, and space science, while Democrats have the advantage in environmental science and public health.

Given these patterns of human behavior, Hardy offered several suggestions for avoiding the exacerbation of political polarization (Box 2-3).

During discussion, one participant called on others to consider that a person’s attitudes and knowledge do not necessarily lead to specific health behaviors. For example, more than 90 percent of seniors got vaccinated against COVID-19, despite differing levels of trust and varying ideologies within this population, the participant noted.

THE CHALLENGE OF EQUITY IN HEALTH AND HEALTH COMMUNICATION

Health inequalities are not a new story, said Viswanath. Despite general gains in public health, inequities persist. For example, public health campaigns and policy changes have resulted in a dramatic decrease in the percentage of people who smoke tobacco, but the decrease has been more dramatic among wealthier, primarily White populations. One reason for the unequal distribution of improvement in public health, Viswanath said, is communication inequalities—“differences among social classes in the generation, manipulation, and distribution of information at the group level, and differences in access to and ability to take advantage of information at the individual level.” Health and well-being are influenced by social drivers such as culture, policy, community, and social networks, and the impact of these drivers on health is mediated through dimensions of communication including access, engagement, processing, and ability to act. Viswanath said that while the drivers themselves can be very challenging to address, interventions in the communication dimensions could potentially mitigate health inequalities. He focused on three domains to address: (a) the digital gap, (b) the mental and emotional toll of poverty and racism, and (c) data absenteeism.

The digital gap is one cause of communication inequality that contributes to persistent health inequalities, according to Viswanath. He said that when he raised the issue of unequal access to digital information 20 years ago, people dismissed his concerns because they believed that cellphones would eventually eliminate the problem. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a number of headlines noted how a lack of internet access worsened disparities in health risks and vaccination rates. Beyond the direct impact on health, lack of internet access made it difficult or impossible for some families to work from home or attend school remotely. Viswanath emphasized that while there has been significant investment in improving broadband access in rural areas, Black Americans and other urban populations are being left behind.

Health communication may also be less effective for some populations due to stress, which can lead to a “mindset of scarcity.” People experiencing poverty are “juggling a lot of things,” said Viswanath, and are forced to differentially allocate their attention (Shah et al., 2012). Stress associated with poverty, racism, and discrimination can interfere with information processing; this relationship is important to consider when planning health communication strategies.

People from groups experiencing social vulnerability are also significantly underrepresented in research, said Viswanath, making it impossible

to draw reliable inferences about these communities (Viswanath et al., 2022). This “data absenteeism” is often blamed on groups being “hard to reach,” but Viswanath suggested that it is due to a lack of investments in infrastructure to reach these communities, a lack of commitment to collecting representative data, and a propensity toward treating communities as “sites for research rather than partners in research.” When efforts are made to recruit participants from underrepresented groups—including poor White people, African American people, Latino communities, people living below the poverty line, and individuals experiencing homelessness—the data can illuminate differences in needs among the groups and suggest ways that health communication could reach groups more effectively.

There are many negative consequences of communication inequalities, said Viswanath, including lower knowledge; norms conducive to unhealthy behaviors; limited or no access to services; inability to act on opportunities even when available; and higher disease incidence, prevalence, and mortality. However, said Viswanath, there are ways to address these inequalities by drawing on communication science. There is a broad body of work in the sciences of communication, community engagement, and participatory science; health communication interventions need to be grounded in this evidence. He shared two examples of practices that could be implemented, which are summarized in Box 2-4.

DISCUSSION

Following the panelists’ remarks about the challenges of health communication in the current political and social climate, workshop participants

and panelists engaged in a discussion focused on how the federal government can work to build capacity in a way that addresses some of the challenges identified. Niederdeppe acknowledged that it is challenging for the federal government to engage with local communities and stakeholders from a considerable distance. He asked panelists to consider whether they see a need to fundamentally change how federal health communication operates. Brady acknowledged the difficulty of this problem and suggested that the federal government could make a greater effort to work hand-in-hand with state and local agencies. Viswanath said that while it is a challenge for the federal government to work with communities, it can be done. Drawing on the science of engagement, he described a process he and his colleagues have used to identify key stakeholders, called “community recognizing sampling”; he described this process as a marriage of positional and reputational approaches. Viswanath and his colleagues interviewed around 30 people in the community from different sectors and made radial charts that illustrated “who is talking to whom.” These data were used to bring people onto advisory boards and engage with the various sectors. Viswanath emphasized that each agency would need its own individualized approach for community engagement, and that it is advisable for all agencies to develop these relationships prior to a crisis happening, not in the midst of one.

Investing in Communication Expertise and Infrastructure

Many panelists and participants mentioned the importance of using evidence-based communication strategies and having the infrastructure in place to support communication, said Niederdeppe. Panelists offered perspectives on ways that federal agencies can best build this expertise and infrastructure. King noted that infrastructure includes regularly evaluating where people go for information, where they want to go for information, and what information they want. “There is a balance between what agencies might want to communicate to interested audiences and what those audiences care about,” he said. Building relationships “on the ground” is important and, once built around one topic of concern (e.g., cancer education) those relationships can pivot to focus on other areas of interest or new platforms. King reiterated that planning for adaptability and flexibility, being proactive rather than reactive, and establishing relationships long before a crisis emerges allow agencies to communicate about multiple health topics (e.g., a new screening recommendation) and disseminate information rapidly when necessary. King emphasized, however, that building these relationships does not erase the impact of social drivers of inequality, noting that agencies need to fund efforts to address social drivers in addition to building a communication strategy. Addressing health inequities requires a

“holistic response and reaction,” so framing it as building infrastructure is a useful way to focus on the broad picture.

Viswanath emphasized that the federal government already has a tremendous amount of expertise in health communication; the issue is ensuring that the people who need to tap into this expertise can do so. He shared an example illustrating the potential of the federal government to make a difference. The Department of Health and Human Services assembled an interagency task force on tobacco that brought multidisciplinary, multiagency expertise into one group; group participants collaborated and shared lessons, then returned to their agencies with new ideas and information. Viswanath underscored the importance of being proactive. As an example, he described a survey to better understand health journalism, since this is an important information source for many people.

Choosing the Right Spokespeople

In discussion, one participant noted that the term “government scientist” creates aversion in a large segment of the population, and asked panelists to speak to the use of science-based approaches to increase trust in government institutions. Hardy agreed that aversion is a considerable problem and noted a recent survey reporting that a sizeable number of people do not trust experts of any type; “‘experts’ is becoming kind of a dirty word to some folks,” he said. Viswanath offered a way to reframe the issue of mistrust in government agencies or experts in general. He drew an analogy to Congress and said that when people are asked if they trust Congress, they often say no, but if asked whether they trust their individual Congressman, they often say yes. When people have a problem or need information, they do not go to a nameless government agency, they go to a specific government agency that has the information and expertise that they need. Viswanath predicted that the poll numbers about trust in government might be quite different if people were asked about specific parts of government. Hardy agreed with this reframing and said that when people are asked a question in the abstract, they tend to rely on their preexisting thought patterns. He gave the example of people saying that they do not trust the public school system as a whole but do trust their own school district or neighborhood school. King agreed that large survey measures of trust are likely not capturing some of the nuance between trust in institutions in general versus trust in specific institutions. He said that by identifying messengers that have retained trust within certain networks, building on and expanding this trust might be possible.

Another participant asked for panelists’ opinions on whether government scientists should be “on the frontlines” talking to the public about their research, or whether scientists should instead focus on ensuring that

those in the media who talk about science have the proper knowledge and understanding. King replied that the appropriate spokesperson for a situation is context dependent, but a communication strategy is needed regardless of who does the talking. Sharing data without putting it in a larger context and without considering the audience is unlikely to be an effective strategy. A workshop participant said that the intentional attacks on institutions and spokespeople are a key challenge for federal health communication, and that when individuals are attacked for speaking up, they are less likely to do so in the future.

One participant asked how federal agencies can humanize themselves by diversifying their spokespeople and building trust through more authentic communication. King said that this is an area in which partner organizations can be very helpful. While a federal agency may not be able to respond to every social media posting or engage in back-and-forth with citizens, a network of partner organizations may be able to fill this role. Further, if the partner organizations are trusted by the community, their relationship with a federal agency could help to improve the community’s trust of the federal agency itself. This is a path, said King, that is immediately actionable and could quickly have potential impact.

When considering who should speak for science, said Niederdeppe, it is important to keep in mind that when pure science goes up against emotion, emotion and storytelling often win. Evidence suggests that emotion and stories matter when engaging with audiences. However, he said, the question is whether a federal agency should be using these communication strategies, or whether an agency should provide the information and allow other partners to communicate the strategic messages. For example, said Niederdeppe, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) could work with partners that develop a brand, a slogan, and a strategy for conveying certain types of information that the CDC wants to disseminate to the public.

This page intentionally left blank.