Pay and Working Conditions in the Long-Distance Truck and Bus Industries: Assessing for Effects on Driver Safety and Retention (2024)

Chapter: 2 Types of Operations, Drivers, and Regulations in Long-Distance Trucking

2

Types of Operations, Drivers, and Regulations in Long-Distance Trucking

The study charge emphasizes an interest in long-distance trucking. This background chapter, therefore, begins by placing the long-distance truckload (TL) sector within the context of the overall trucking industry, including the other long-distance trucking sectors, and describes how carriers in the TL sector operate. It then describes the overall truck driver workforce and places TL drivers within that larger workforce. Distinctions are made among TL drivers who are employees of trucking companies and independent owner-operators who may either transport freight under their own operating authority or contract their services to larger trucking companies.

The discussion then turns to the regulatory environment of trucking by providing an overview of the main bodies of pertinent federal regulations applicable to safety and labor standards.1 The chapter briefly recounts the history and impact of the Interstate Commerce Commission’s (ICC’s) decades-long economic regulation of interstate trucking, and how the industry was fundamentally reshaped when the regulations were lifted during the period of economic deregulation that swept through transportation during the 1970s and 1980s. The deregulated trucking industry has become highly competitive and cost-conscious, affecting how drivers are compensated. Also pertinent to this study’s focus on driver compensation and safety are the federal safety regulations governing driver licensing and on-duty hours of service (HOS). These regulations are discussed because they have a

___________________

1 Much of the regulatory environment and legal requirements mentioned in this chapter refer to interstate carriers. Many of the same regulations, however, will also apply to local and intrastate carriers.

bearing on truck driver pay methods and levels by affecting both the supply of qualified drivers and the amount of time a driver can be behind the wheel earning pay.

The chapter concludes with a discussion of the treatment of long-distance truck drivers and their compensation under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). Administered by the U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL), this legislation deserves discussion because of its intersections with the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s (FMCSA’s) HOS regulations and the exemptions that it grants to trucking companies from providing drivers with overtime pay.

TRUCKING OPERATIONS

Trucking operations in the United States are highly diverse. As a statistical category, “heavy duty trucks” consist of a lighter category (Class 7), with gross vehicle weight ratings (GVWRs) between 26,001 lb and 33,000 lb, and a heavier category (Class 8), with GVWR between 33,001 lb and 80,000 lb.2 Both categories can include straight trucks, such as refuse and dump trucks, and combination trucks consisting primarily of truck tractors pulling semitrailers. According to data published by the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics, there were a total of 2.8 million heavy-duty trucks in the United States in 2019, of which more than 95 percent were truck tractors.3 The latter vehicles are the focus of this report because of the study’s interest in long-distance (150 miles or more) trucking, which is dominated by tractor-trailer trucks. It is important to note, however, that because drivers of Class 7 and Class 8 trucks must have a commercial driver’s license (CDL), the varied trucking segments that use heavy trucks for hauling freight and providing other non-freight services will compete with one another for qualified drivers.

When focusing on the transportation of freight, trucking operations can be differentiated in several ways. The first distinction is between for-hire and private carriers. A for-hire carrier is in the business of moving freight for paying customers, while a private carrier moves freight that it owns or distributes as part of its main line of business, such as delivering supplies and parts to factories or restocking grocery stores and filling stations. A second distinction concerns the distance over which the freight is moved. Local carriers, including providers of marine container drayage, operate over short distances (generally under 150 miles), while long-distance

___________________

2 Some trucks are even heavier, as trucks with GVWRs of more than 80,000 lb are allowed under permit on some highways in some states.

3 Table 1-22b, U.S. Truck Registrations by Type, 1995–2019, www.bts.gov/browse-statisticalproducts-and-data/national-transportation-statistics/number-us-truck.

carriers operate regionally and nationally. The line dividing a local shipment from a long-distance shipment varies depending on the dataset and analytic purpose. For this study’s purposes, trucks carrying shipments 150 miles or more from the pickup location to the drop off location is considered a long-distance move.

A third distinction is between specialized and general freight. Some carriers specialize in the movement of certain types of freight that require special equipment and can require specific driver qualifications. Examples of specialized freight are bulk steel hauled on flatbed trailers, bulk chemicals (including hazardous materials) hauled in tank trailers, perishable goods hauled in insulated and refrigerated trailers, and gravel hauled in dump trailers. Most carriers focus on moving general freight, usually in dry van semi-trailers. The most common dry van trailer is 53 feet long, 8.5 feet wide, and 13.5 feet high, which is the largest trailer size permitted on the entire National Highway System.

A significant fourth distinction is among carriers that specialize by shipment size. The three shipment size types are TL, less-than-truckload (LTL), and parcel. TL freight fills a semi-trailer to either its maximum volume or maximum weight. While most TL shipments are general freight transported in enclosed dry vans, specialized freight is also usually hauled in truckload lots. By comparison, LTL freight consists of a range of shipment sizes and freight types that do not fill a semi-trailer and therefore are combined with freight from other shippers to form a complete load. Parcel carriage is a form of LTL freight involving the transportation of small packages generally weighing much less than 150 lb.

Although a trucking company may have operations in more than one of these domains, carriers have strong incentives to specialize in one type of operation (Muir et al. 2019). Significantly, both parcel and LTL carriers operate as network businesses, in which originating shipments are consolidated at local terminals for dispatching as full loads and transported in linehaul to other local terminals, where the shipments are separated for delivery. However, parcel carriers are even more specialized, as they deploy handling equipment (e.g., conveyor belts, sorting technology) specific to small packages at their local terminals, while LTL carriers use more general-purpose equipment (e.g., forklifts).

In contrast to parcel and LTL carriers that move freight through networks, TL carriers usually operate in a point-to-point fashion, moving full loads from a shipper to the consignee, and then moving the empty trailer to a new shipper (“deadheading”) to pick up another TL shipment. As a result, TL carriers do not generally require terminals for handling and sorting freight, although they may have terminals to house office staff and to park and maintain vehicles. It merits noting that TL carriers will tend to have more semitrailers than they have truck tractors and drivers. This is

because TL carriers that transport general freight will often negotiate with shippers and receivers to ensure that drivers do not need to be present during the loading and unloading of trailers, which can then be left at origin and destination facilities for the period of time needed for shipment loading and unloading.4 However, in the case of specialized TL freight, the driver will usually be present during the loading and unloading of the cargo to ensure proper handling and positioning on the trailer.

Table 2-1 summarizes various statistics on trucking companies (excluding owner-operators) in the for-hire trucking business during 2017 but limited to TL (general and specialized) and LTL carriage. The data, which are derived from the Economic Census, show that long-distance for-hire trucking is an unconcentrated and competitive industry. The TL sector is especially competitive, as it consists of thousands of small carriers, a moderate number of middle-sized carriers, and relatively few large carriers. Although not shown in the table, the four largest carriers providing long-distance general-freight TL services accounted for only about 15 percent of the revenues generated by that subsector during 2017. Likewise, the four largest carriers in long-distance specialized-freight TL services accounted for only about 13 percent of the revenues in that subsector.

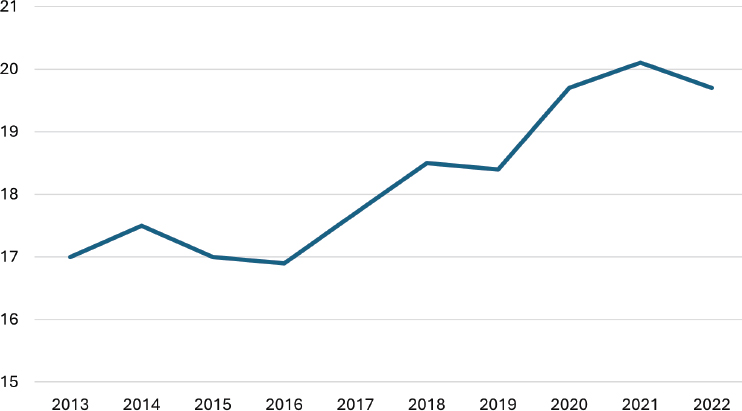

The data in Table 2-1 are limited to carriers that employ drivers and therefore do not include drivers who are owner-operators, which are sole proprietorships without employees. As contractors to carriers and by providing independent services, owner-operators play a major role in the long-distance TL sector. The number of owner-operator drivers is not clear; however, Figure 2-1 provides some indication of their role based on the percentage of total truck transportation revenue that non-employer firms generate according to annual surveys conducted as part of the Economic Census. Owner-operators regularly account for between 15 and 20 percent of this revenue.

Long-Distance Truck Driver Workforce

According to the Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, there were 2,044,400 workers employed as “Heavy and Tractor-Trailer Truck Drivers” as of May 2023.5 Carriers in the for-hire trucking industry employed 917,010 of these drivers, or about 45 percent of the total. Of these 917,010

___________________

4 Drivers handling preloaded or customer-unloaded general TL freight may still be held at customer locations by paperwork issues, but seldom because of the time required for loading or unloading.

5 A reliable accounting of the persons employed at non-farm business establishments in each occupation is provided in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, using occupations as defined in the Standard Occupational Code. Data are provided annually for each during May of the year, www.bls.gov/oes.

TABLE 2-1 Relative Sizes of the Long-Distance, For-Hire Trucking Sectors (Except Owner-Operators and Less Than Truckload Parcel Carriers)

| Type of Operation | Number of Firms | Annual Revenue ($1,000) | Number of Employees | Percentage of Firms | Percentage of Annual Revenue | Percentage of Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL General Freight | 31,908 | 112,441,276 | 519,358 | 66% | 54% | 52% |

| TL Specialized Freight | 11,729 | 50,894,893 | 217,654 | 24% | 24% | 22% |

| LTL Freight | 4,410 | 46,191,773 | 271,447 | 9% | 22% | 27% |

| Total | 48,047 | 209,527,942 | 1,008,459 | 100% | 100% | 100% |

NOTES: The 2017 data are presented because the Economic Census is performed every 5 years and the data for 2022 are not yet available. All nationally representative data collected by federal agencies are based on the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS). In this system, data on for-hire trucking operations are collected primarily within the category “NAICS 484, Truck Transportation.” LTL = less than truckload; TL = truckload.

SOURCE: 2017 Economic Census, U.S. Bureau of the Census, www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/2017-economic-census.html.

NOTE: Non-employer firms are generally owner-operators.

SOURCE: Committee generated from NAICS 484 data in the Service Annual Survey of the U.S. Census Bureau, www.census.gov/programs-surveys/sas.htm.

drivers, an estimated 45 percent work for long-distance general-freight or specialized-freight TL carriers, totaling about 425,000 drivers.6 A reasonable estimate, therefore, is that about 1-in-5 heavy-truck and tractor-trailer truck drivers work for long-distance TL carriers.

TL drivers vary in their relationship with carriers and shippers. Employee drivers, often referred to as “company” drivers, are directly employed by the trucking company that owns the equipment (both trucks and trailers) they operate. The carrier, therefore, is usually responsible for the costs associated with operating the equipment and for obtaining the loads for employee drivers. As with other employee relationships, the carrier is responsible for the employer’s portion of payroll taxes. The carrier also pays part of the cost of nonwage benefits, such as pay for some holidays and for health insurance when offered. More details on how company drivers are

___________________

6 According to the 2017 Economic Census (the most recent available at the time of writing), the general freight long-distance truckload segment (NAICS 484212) had 35.1% (519,358) of all the employees in for-hire trucking and the specialized freight long-distance segment (NAICS 484230) had 15.6% (217,447), www.census.gov/programs-surveys/economic-census/year/2017/economic-census-2017/data.html. To arrive at these estimates, the value of 57.8% of all employees as heavy-duty truck drivers from the Occupational Employment and Wages data was multiplied by the total employee numbers for each segment.

compensated, including their status with respect to the FLSA, are discussed below and in later chapters.

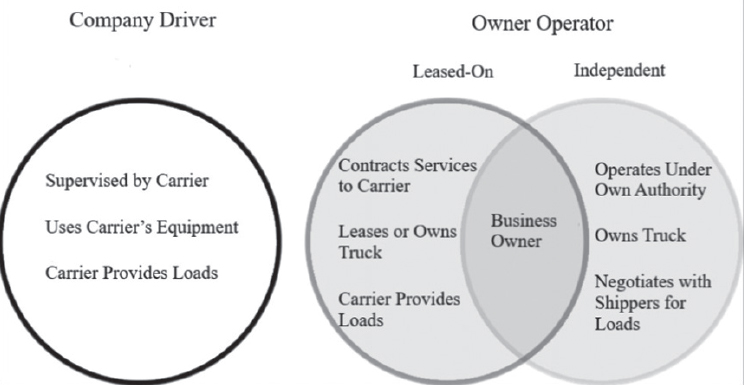

Employee drivers are to be distinguished from owner-operators, who are independent contractors who own or lease their equipment, mainly truck tractors and semitrailers. As shown in Figure 2-2, there are two types of owner-operators: (a) those who transport freight under their own operating authority, and (b) those who lease their services to trucking companies, subject to the requirements of any equipment financing or lease agreement. Owner-operators who operate under their own authority solicit and accept freight for compensation directly from shippers or freight brokers. These operators are, in essence, functioning as very small TL trucking companies. In contrast, owner-operators who lease their services to a trucking company (i.e., “leased-on” drivers) commit their equipment and driving services exclusively to that carrier for a period. Leasing allows the owner-operator to leverage the carrier’s freight and purchasing networks for loads and to potentially obtain lower prices on expense items such as fuel, tires, and maintenance services.

Owner-operators and drivers employed directly by long-distance TL carriers have working conditions that are distinctly different from drivers of LTL and private carriers, nearly of which are company drivers. Long-distance drivers employed by LTL firms generally drive regular routes connecting the carrier’s network of terminals, which permit more predictable schedules and times at home. Likewise, long-distance drivers for private carriers also drive more regular schedules over familiar routes between

NOTE: The sizes of the circles are not meant to represent the number of drivers of each type.

suppliers and destination points. By comparison, long-distance drivers employed by TL carriers will usually have less schedule consistency and predictability as they haul freight for multiple customers with origins and destinations that vary based on demand. Nevertheless, it merits noting that some TL carriers provide dedicated carriage to shippers that substitutes for private carriage. Also, some TL carriers provide marine container drayage services between warehouses and gateway ports and rail terminals. Drivers for these TL carriers will have more predictable routes and work schedules than drivers for most TL carriers.

REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT

The bulk of federal regulations in effect today are focused on ensuring the safe operations of motor carriers and are administered and enforced by FMCSA. For many decades, however, interstate trucking was subject to restrictions on the rates carriers could charge and the services they could provide under a regulatory regime administered by ICC. While nearly all those regulations have long-since been withdrawn, USDOL continues to retain a role in regulating aspects of the trucking industry’s employment of drivers, particularly through its administration of the FLSA.

Economic Regulation and Deregulation

In its early days, during the first quarter of the twentieth century, the U.S. trucking sector, operating as a new and comparatively small industry, enjoyed substantial freedom from economic regulation. However, as the scope of the U.S. highway system increased, along with the size and carrying capacity of trucks, trucking companies began to compete with railroads for more long-distance freight. This modal competition created pressure for interstate trucking to be subject to the same kind of price and service regulation as railroads.

A milestone in the history of the U.S. trucking industry was the passage of the Motor Carrier Act (MCA) of 1935. Before the passage of this act, the trucking sector operated largely under only non-uniform, state-level regulation (Freund 2007). The MCA gave ICC the authority to regulate various aspects of the interstate trucking industry’s economics, including market entry and competition, the routing of goods, and the setting of rates (called tariffs), typically on the basis of distance, weight, and class (type) of goods transported. Carriers were required to obtain licenses, which subjected them to regulatory scrutiny to ensure compliance with economic and financial regulations as well as safety standards (Nelson 1936).

Although these rate and entry regulations were introduced under the pretense of maintaining an economically healthy and competitive freight

transportation system, by the 1950s many economists concluded that the ICC regulatory framework was stifling innovation and competition by limiting market access by new entrants and preventing new service offerings (Adams 1958a, 1985b; Meyer et al. 1959). With the creation of the Interstate Highway System by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, the prospects of trucks playing an increasingly larger role in the nation’s freight system had become evident and pressure grew during the 1960s and 1970s to remove the decades-long economic restrictions on the industry. Advocates of deregulation argued that the trucking industry would become more efficient, responsive to customers, cost-conscious, and innovative, which were the same arguments that succeeded in deregulating the airline, railroad, and intercity bus sectors during the same period.

Congress passed the deregulatory Motor Carrier Act of 1980 (MCA80) with the stated goal of eliminating excessive and inflationary government restrictions and red tape. MCA80 eliminated barriers to entry into the trucking industry and allowed existing carriers to streamline their operations, such as by specializing in specific services (such as TL or LTL operations), and expanding into new markets (Corsi et al. 1992). Moreover, MCA80 abolished ICC’s authority over rate-setting, allowing carriers and shippers to negotiate private rates rather than consult published tariffs.

MCA80’s removal of strict regulatory controls on trucking rates and on market entry helped bring about a more dynamic marketplace for trucking services. Negotiated private rates ended up reduced shipping costs for businesses.7 Because of the limited capital required for entry into the TL sector, the economic deregulation of this sector was especially transformative, and the reason why it is now characterized by a small number of large and medium-size companies and thousands of smaller service providers (including individual owner-operators) that compete by offering uniform low-cost service rather than competing by differentiating their services and brand.

Safety Regulation

Even as economic regulations imposed on the trucking industry were withdrawn, the federal government’s regulation of safety increased, perhaps out of concern that the churn within the industry could lead to less safety vigilance. During deregulation, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) was responsible for developing and enforcing federal motor carrier safety regulations. In 1986, Congress passed the Commercial Motor Vehicle Safety Act, which called on FHWA to standardize the minimum requirements for

___________________

7 See www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/regulatory-reform-and-truckingindustry-evaluation-motor-carrier-act-1980/198203truckingindustry.pdf.

obtaining and retaining a commercial driver’s license.8 FMCSA was created in 2000 by the Motor Carrier Safety Improvement Act of 1999.9 FMCSA was immediately charged with updating (HOS) regulations and establishing stricter requirements for carriers to maintain safety records.

Hours of Service Regulation

HOS regulations are intended to protect a driver’s health and to promote road safety by reducing crashes caused by fatigue. The regulations seek to do so by limiting the number of hours a truck driver can work, both consecutively and within a specific period, and by requiring drivers to take periodic rest breaks. The MCA of 1935 had originally assigned ICC responsibility for establishing these duty-time regulations and the commission’s first regulations were issued in 1937 (Lockridge 2020). In 1966, when FHWA was created, responsibility for HOS and other motor carrier safety regulations was transferred from ICC.

In their early iterations, the HOS rules limited truck drivers to 60 hours of work in a 7-day period or 70 hours of work in an 8-day period. The regulations also limited drivers to 16 hours on-duty and required 8 hours off-duty in a 24-hour period.10 Although the rules remained largely unchanged after economic deregulation, FHWA was charged by congress with amending them during the 1990s. It was not until January 2004, however, that FMCSA (as successor to FHWA) made significant changes to the HOS rules to address concerns about driver fatigue. These changes included:

- changing the limit on driving time to 11 hours;

- decreasing the limit on total work time to 14 total hours; and

- increasing mandatory off-duty time to 10 hours.

The updated HOS rules were intended to return drivers to a 24-hour cycle.11 Under the earlier HOS regulations, drivers could extend the workday by logging breaks or waiting time as off-duty time. The new rules prohibited drivers from extending their driving time in this manner: drivers must stop driving after 11 hours and stop working 14 hours after they begin working, regardless of breaks taken for meals or rest (Peoples 2018).

___________________

8 The requirement was intended to improve highway safety by removing unsafe commercial motor vehicles and unqualified and unsafe drivers from the roads.

9 49 USC § 113.

10 Federal Register, Vol. 85, No. 105, Monday, June 1, 2020.

11 Assuming drivers take full use of the available hours of driving, the shortest the cycle allowable under these 2004 changes was 21 hours. Under the previous HOS rules, the shortest allowable cycle was 16 hours.

Electronic Logging Devices

During the early days of the HOS regulations, drivers were required to keep paper logbooks as proof of their duty status. However, paper logbooks came under scrutiny as both time-consuming for drivers and as easily falsified (TruckingInfo 2017).12 In response, FMCSA began requiring the installation of electronic onboard recorders in 2007 by carriers with a history of HOS violations.13 In 2017, FMCSA required the use of electronic logging devices (ELDs) by most motor carriers.14 By automating the logging of a truck’s movement, the purpose of ELDs is to improve compliance with HOS restrictions.

Regulation of Driver Compensation

Most of the regulations that govern the rights of truck drivers and other employees in the motor carrier industry are established and enforced by USDOL. For example, although truck driver working hours are enforced by FMCSA through HOS regulations and the ELD mandate, driver compensation legislation that governs remuneration of drivers during driving, non-driving, and off-duty hours is administered by USDOL. The USDOL regulations—codified under the FLSA—were enacted in 1938.15 They define minimum wages,16 overtime pay, and other federal wage provisions. The FLSA regulates compensation paid to employee drivers while on-duty and during non-driving and off-duty time.17

As a result of the separation of jurisdiction between FMCSA and USDOL, issues can arise at the intersection of the FLSA and HOS requirements.18 Moreover, a 1966 amendment to the FLSA, known as the Motor

___________________

12 See www.truckinginfo.com/157837/70-answers-to-top-eld-questions.

13 According to FMCSA, “motor carriers that have demonstrated serious noncompliance with the HOS rules will be subject to mandatory installation of EOBRs [electric on-board recorders] meeting the new performance standard.” See www.fmcsa.dot.gov/sites/fmcsa.dot.gov/files/docs/EOBR_final_rule_0.pdf.

14 See www.federalregister.gov/documents/2015/12/16/2015-31336/electronic-loggingdevices-and-hours-of-service-supporting-documents.

15 See www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/WHD/legacy/files/FairLaborStandAct.pdf.

16 The FLSA currently requires employers to pay employees a minimum rate of at least $7.25 an hour for each hour of work (29 USC § 206).

17 29 C.F.R. § 785.22.

18 For example, the FLSA allows employers to exclude a sleeping period of no more than 8 hours per day when calculating an employee’s compensation (29 C.F.R. § 785.22). The HOS regulations allow drivers to drive for up to 11 hours per day, leaving 13 hours for sleep. The FLSA would require the driver to be paid for as many as 5 of those hours.

Carrier Exemption (MCE),19 exempts motor carriers from compliance with the act’s overtime pay provisions. Although the FLSA guarantees overtime pay to many workers, it specifically exempts employees in sectors over which the FMCSA has authority to establish qualifications and HOS. By and large, this exemption applies to employees whose primary job responsibilities involve the transportation of goods in interstate commerce (irrespective of whether those individuals themselves cross state lines). As a result, employee drivers in the trucking industry are exempt from overtime pay requirements (the MCE does not exempt drivers from the protections of other provisions of the FLSA, such as minimum wage requirements and child labor laws).

Litigation in a changing gig-based economy has brought increasing attention to the MCE and how carriers apply it to their drivers. Because the exemption typically applies only to employee drivers, a driver’s classification as an employee or as an independent contractor largely determines whether a driver that is not involved in interstate transportation is entitled by the FLSA to overtime pay and related employee benefits. Independent contractors, who are typically in business for themselves, do not qualify for the same wage protections (minimum wage, overtime pay, etc.) afforded to employee drivers. This issue becomes even more complex in the trucking industry because of the two distinct categories of independent contractor operations—owner-operators who contract their services using their own operating authority and owner-operators who operate under another motor carrier’s authority in a lease arrangement (i.e., leased-on drivers).

In March 2024, USDOL finalized a rule clarifying which workers should be classified as independent contractors and which should be classified as employees and afforded the full minimum wage, overtime, and other protections provided under the FLSA across all industries.20 According to this rule, “independent contractor” refers to workers who, as a matter of economic reality, are not economically dependent on an employer for work and are in business for themselves.

This new rule has implications for leased-on owner-operator truck drivers, as they may be classified as employees of the carrier for FLSA purposes. Because the MCE applies only to employee drivers, if congress removes the MCE and thereby restores overtime pay for employees in interstate transportation, the distinction between an owner-operator who is classified as an

___________________

19 Section 13(b)(1) of the FLSA provides an overtime exemption for employees who are within the authority of the Secretary of Transportation (DOT/FHWA) to establish qualifications and maximum hours of service pursuant to Section 204 of the Motor Carrier Act of 1935, except those employees covered by the small vehicle exception. See www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/docs/whdfs19.pdf and www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fact-sheets/19-flsa-motor-carrier.

20 Federal Register, Vol. 89, No. 7, Wednesday, January 10, 2024.

employee and one who is classified as an independent contractor will likely determine whether that driver earns overtime pay. To further complicate the issue, several states have overtime pay regulations that both differ from one another and from the federal standards established by the FLSA. These state-specific regulations often provide additional protections and benefits for employees. One of the most visible and perhaps impactful examples of these driver classification issues is California’s recent Assembly Bill 5, discussed in Box 2-1.

BOX 2-1

California Assembly Bill 5

Also known as the “gig-worker” legislation, California’s AB5 (which went into effect January 1, 2020) redefines the employment status of workers by reclassifying many workers that were previously classified as independent contractor as employees. AB5 was enacted in 2019 and has since spawned significant debate and litigation about the evolving nature of work and, relatedly, worker classification. Although many workers in the gig economy are classified as independent contractors, proponents of AB5 maintain that these workers are employees who have been deliberately misclassified as independent contractors to deny them certain labor rights and benefits traditionally afforded to employees. The legislation sought to address the misclassification issue by establishing a more stringent test for determining whether a worker should be classified as an employee or as an independent contractor.

Under the so-called “ABC Test,” a worker is presumed to be an employee, and not an independent contractor, unless the employer can demonstrate all three of the following: (A) the worker is free from control and direction in the performance of services; (B) the worker is performing work outside the usual course of the business of the hiring company; and (C) the worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business.a

Thus, for an owner-operator to demonstrate independence, the A test may require the operator to prove that it has substantial control over deciding when, where, and how to transport goods while retaining the freedom to work for multiple carriers rather than being tied exclusively to one carrier. Furthermore, a potential implication of the B test is that leased-on owner-operators would have to be treated as employees because their usual course of business is hauling freight, which is the same line of business as the carrier.b

__________________

a See https://www.labor.ca.gov/employmentstatus/abctest.

b See https://www.labor.ca.gov/employmentstatus/abctest and https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/abc_test.

REFERENCES

Adams, W. (1958a). The role of competition in the regulated industries. The American Economic Review, 48(2), 527–543.

Adams, W. (1958b). The regulation of American industry. Diogenes, 6(24), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/039219215800602405.

Corsi, T. M., Grimm, C. M., and Feitler, J. (1992). The impact of deregulation on LTL motor carriers: Size, structure, and organization. Transportation Journal, 32(2), 24–31.

Freund, D. (2007). Motor carrier safety laws and regulations. In The domain of truck and bus safety research. Transportation Research Circular E-C117, pp. 25–40. Transportation Research Board of the National Academies.

Lockridge, D. (2020). Hours of service timeline: The long, convoluted history of truck driver rules. www.truckinginfo.com/10121114/hours-of-service-timeline-the-long-convolutedhistory-of-truck-driver-rules.

Meyer, J. R., Peck, M. J., Stenason, J., and Zwick, C. (1959). The economics of competition in the transportation industries. #107 Harvard Economic Studies. Harvard University Press.

Nelson, J. C. (1936). The Motor Carrier Act of 1935. Journal of Political Economy, 44(4), 464–504. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1823197.

Peoples, J. (2018). Industry performance following reformation of economic and social regulation in the trucking industry. In D. Belman and C. White (Eds.), Trucking in the age of information (pp. 127–146). Routledge.