Pay and Working Conditions in the Long-Distance Truck and Bus Industries: Assessing for Effects on Driver Safety and Retention (2024)

Chapter: 4 Driver Retention and Turnover in Long-Distance Trucking

4

Driver Retention and Turnover in Long-Distance Trucking

This study is expected to examine the effects of compensation methods and work conditions on driver retention in long-distance trucking. Therefore, this chapter examines this issue, while concentrating on the for-hire long-distance truckload (TL) sector. The chapter begins by explaining what is meant by driver retention and the related matter of driver turnover, as low rates of driver retention imply high rates of driver turnover. A key consideration is whether driver retention and turnover are to be considered at the carrier level within the long-distance truckload TL sector or more broadly at the occupational level. In other words, is the concern about drivers leaving one long-distance TL carrier for another, choosing to work for firms engaged in other kinds of heavy-duty trucking, or leaving the occupation of truck driving altogether? The reasons for the chapter’s focus on driver retention and turnover at the TL carrier level are explained.

The discussion then turns to the academic literature on factors that may contribute to a driver deciding to remain in or leave the employment of a particular long-distance TL carrier. The American Trucking Associations (ATA) periodically surveys its member trucking companies but reports only average turnover rates and not the variation around the average. Anecdotal evidence suggests that high driver turnover is both common and persistent among TL carriers. Thus, for context in trying to understand the possible role of compensation and work conditions on driver turnover, it is helpful to consider economic and structural characteristics of the long-distance TL sector that could make it prone to high driver turnover. In this regard, the academic literature focuses on the fact that long-distance TL service is provided like a commodity, as the sector has many suppliers that are

competing primarily on cost and by offering low price service rather than by differentiating their brand and services to seek a premium rate. For reasons that will be explained, this characteristic is relevant to both the driver compensation methods used and the working conditions in the TL sector, because they each play a role in a carrier’s ability to manage costs.

Finally, consideration is given to frequent claims that the long-distance TL sector suffers from unusually high and persistent driver shortages. Such labor shortages, if real and persistent, could also explain why long-distance TL carriers seem to be constantly recruiting and competing with one another for drivers. Understanding the causes of the shortages would also be necessary for understanding the possible effects of compensation methods on turnover. The chapter therefore concludes by applying insights from labor economics, which suggest that claims of long-term driver shortages are spurious and not likely to be helpful in explaining the sector’s driver turnover patterns and the possible influences of compensation.

RETENTION AT THE OCCUPATIONAL AND CARRIER LEVELS

The long-distance TL sector (as noted in Chapter 2) employs only about one in five drivers in the general occupation of “heavy-duty truck driver,” as designated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).1 Thus, distinguishing driver retention in long-distance TL trucking from retention in the general occupation of heavy-duty truck driving is important because empirical evidence suggests that drivers of heavy-duty trucks have levels of occupational attachment that are typical of most similar occupations. For instance, in analyzing nationally representative data on heavy-duty truck drivers from 2003 to 2017, Burks and Monaco (2019) found that approximately 82 percent of drivers employed in for-hire trucking kept the same general occupation from year to year. The authors determined that this is a normal rate of occupational attachment, consistent with the 18 percent occupational mobility found in studies for all workers (Kambourov and Manovskii 2008).

The empirical evidence also suggests that hours and earnings matter for attracting workers to the occupation of heavy-duty truck driving and for retaining them. Burks and Monaco (2019) found that individuals are more likely to become and remain heavy-duty truck drivers when the hours and earnings of heavy-duty truck drivers were more attractive than the hours and earnings in occupations demanding similar investments in human capital (e.g., education). In a related study, Phares and Balthrop (2022) analyzed the responsiveness of individuals who could enter the truck driver occupation to wage differences between trucking and occupations in other industries that are significant sources of truck drivers. They found that

___________________

1 BLS Standard Occupational Code 53-3032.

truck drivers are even more sensitive to wage differences than are workers in other occupations requiring similar investments in human capital.

The interest of this study is about driver retention and turnover as experienced by carriers in the long-distance TL sector, and less so about retention of drivers by employers engaged in heavy-duty trucking generally. Research indicates that driver retention and turnover rates experienced by TL carriers can be explained in part by the cyclical factors experienced across all carriers in the sector and trucking generally (Miller et al. 2021). That is, when the general trucking industry workforce is expanding because of an upturn in freight demand, there will be higher turnover in this sector at the carrier level and during a downturn in freight demand there will correspondingly be lower turnover. This is true because during an upturn, aggressive driver recruiting will bring in more new-to-the-industry drivers who are prone to exit rapidly from long-distance TL jobs. Sign-on bonuses offered to experienced drivers enticing them to switch employers will also be more common. Conversely, when the demand for freight trucking is decreasing, turnover will be lower in this sector, as there will be both fewer new-to-the-industry drivers and fewer enticements and opportunities for experienced drivers to change firms.

Cyclical factors affecting the demand for, and supply of, heavy-duty truck drivers are discussed again later in this chapter when considering claims of chronic driver shortages, but the literature also points to noncyclical factors that coincide with a driver’s decision to remain with or leave a given carrier. The committee reviewed more than two dozen academic studies of such factors. Full details and a table of the studies reviewed appear in Table 4A-1 in the addendum to this chapter. Some of the reviewed studies found differences among drivers in how pay and working conditions relate to their likelihood of remaining with or leaving a particular employer (Garver et al. 2008; Williams et al. 2011). Others showed how specific features of pay and working conditions can be associated with higher or lower rates of retention and turnover. In some cases, the factors identified may be controlled by a carrier, while in other cases they may not be readily controlled. As an example of the latter, one study found that new-to-the-industry drivers with higher basic cognitive skills are far less likely to change employers (Burks et al. 2009).2

Other notable findings from the studies, which show associations but do not necessarily explain the causes of turnover, include the following:

- Variability in earnings increases turnover. More variability in driver earnings on a weekly basis is associated with higher turnover, while

___________________

2 See also the summary in Appendix A of the study’s interviews of drivers at truck stops. Some of the drivers noted personal reasons for staying with or leaving trucking companies.

- Frontline supervisors matter. Effective frontline supervisors—who are primarily dispatchers in smaller TL carriers but may have other positions in larger carriers with dedicated dispatchers—coincide with decreased driver turnover, while ineffective supervisors increase driver turnover (Keller and Ozment 1998, 1999a, 1999b).

- Recruitment strategies matter. Drivers recruited through referrals from current drivers appear less likely to leave the carrier (Suzuki et al. 2009; Burks et al. 2015).

- Regularity matters. Even when pay is held constant, drivers assigned to serve particular shipper for lengthy period have lower turnover than drivers who are dispatched to loads randomly (Burks et al. 2006).

- Driver groups leave carriers at different rates. New-to-industry drivers quit at higher rates than experienced drivers, at least after they have been with their initial employer long enough to have repaid their training costs (Burks et al. 2006).

less weekly variability is associated with lower turnover (Conroy et al. 2022). The studies find that piece-rate pay (including pay-per-mile), which is intended to reward consistent and diligent work effort but depends on the availability of loads, can lead to more variability in a driver’s weekly earnings, which many drivers dislike. As might be expected, increases in the piece rate itself (i.e., higher pay for each mile traveled), which lead to higher earnings for the same amount of effort, coincide with reduced turnover, while decreases in the piece rate coincide with increased driver turnover by providing a lower reward for effort (Suzuki et al. 2009; Conroy et al. 2022).

Some of these findings, including the interest of drivers in making predictable earnings and having more regular schedules, are suggestive of how both working conditions and pay in the long-distance TL sector may be factors in driver turnover and retention. By any measure, the work requirements and conditions in the sector cannot be described as regular. As discussed in Chapter 2, long-distance TL carriers primarily provide point-to-point service between shipper and consignee locations. Because freight demand is distributed geographically and temporally in a partially random manner, drivers are dispatched from place to place, either within a region, across regions, or nationally, depending on the scope of their carrier’s business. Additionally, because the needs of shippers and consignees vary, as do conditions enroute to serve them, such as traffic congestion and weather, a long-distance TL driver’s work hours tend to be long and the work schedules tends to vary across both day and night (Powell et al. 1988; Belman et

al. 2004; Burks et al. 2008; Suzuki et al. 2009; Monaco and Burks 2010; Chen et al. 2015; Viscelli 2016; Li et al. 2022). As a result, and recognizing that there are variations across firms and specific jobs, TL drivers tend to have highly irregular work schedules, work long hours per week, and have uncertain and limited time at home (Monaco and Burks 2010; Viscelli 2016). Moreover, these irregular working conditions can lead to unpredictable and fluctuating weekly earnings, as load availability may change from week to week and shipment distances (and thus miles paid) may increase or decrease. As noted in Chapter 1 and summarized in Appendix A, the interviews of long-distance truck drivers conducted for this study surfaced concerns about irregular pay in addition to irregular schedules.

As noted in Chapter 2, less-than-truckload (LTL)3 linehaul drivers and long-distance drivers in private fleets also drive long distances and they too can have long work weeks. But they generally face significantly less uncertainty about their schedules, dispatching, and time at home because they normally run only between their firm’s own terminals (in the case of LTL drivers) or between the freight docks controlled by their employer and a limited set of supplier or customer locations (in the case of private-carrier drivers). As ATA’s chief economist has remarked when discussing long-distance TL driver supply issues, “LTL and private fleet drivers are generally paid more and are home more often” (Costello and Karickhoff 2019). Indeed, human resource firms serving the long-distance TL sector acknowledge that although many individual factors can influence driver retention, the top reasons are pay-related (level, variability, and unpaid time) and time at home (amount and variability) (Ricks 2020; Coker 2022; Kuder 2022). Indeed, in this study’s interviews of truck drivers (Appendix A), time spent away from home was cited as a drawback of long-distance truck driving.

Although anecdotal, it is nevertheless interesting that in this study’s interviews of long-distance truck drivers, almost two-thirds of participating drivers indicated that they planned to remain in the long-haul trucking industry, compared to about half who said that they planned to stay with their current carrier. Most of the drivers who wanted to leave their employer cited either a need for better wages or a desire to work for a local delivery carrier or heavy-truck operator. Most drivers did not state a reason for planning to leave the sector, but the few that did, cited the need to spend more time at home.

___________________

3 As described in Chapter 2, LTL carriers primarily handle smaller shipments than do TL carriers. As a result, they maintain a network of local terminals at which these smaller shipments are combined into full loads to move between terminals, and at which incoming full loads are broken down into separate smaller shipments for local delivery.

SOURCES OF HIGH TURNOVER

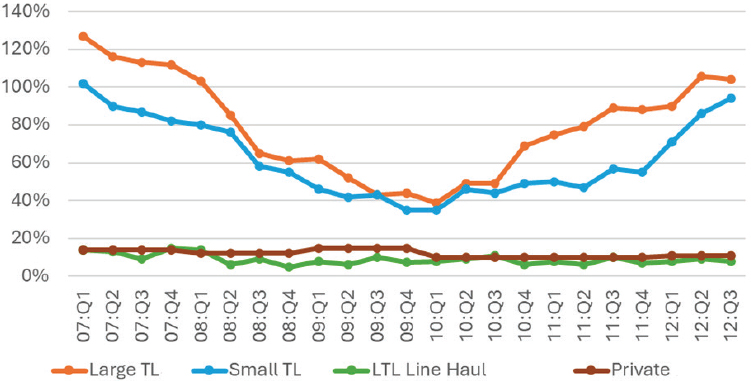

Notwithstanding the possible influences on turnover of the various factors cited above, the strong evidence of persistently high turnover rates in the TL sector warrants further explanation. Notably, for more than 25 years, ATA has surveyed the annualized driver turnover rates of long-distance TL carriers. This rate is simply the percentage of drivers employed during the year that left employment, including new recruits who may have spent only a few days or weeks on the job. Since 2013, the results from these surveys have been presented in ATA’s trade publication, the Quarterly Employment Report.4 According to these reports, the average annualized turnover rate from the third quarter of 1996 through first quarter of 2023 was 92.7 percent for large TL carriers (i.e., those earning $30 million or more in annual revenue) and 77.6 percent for small TL carriers earning less than $30 million in annual revenue.

ATA also surveyed LTL carriers from the fourth quarter of 2000 through the first quarter of 2022. In contrast to the long-distance TL sector, the reported annualized turnover rate for linehaul5 drivers in LTL carriage averaged only 11.8 percent during this period. An additional comparison appears in the annual reports of the National Private Truck Council (NPTC).6 As discussed in Chapter 2, private carriers are operated by firms in support of their mainlines of business, so they are not part of the for-hire trucking industry. However, because these carriers also employ drivers who operate over long distances, they form a second, at least partly relevant, comparison group (Costello 2019). NPTC reports that annualized driver turnover rates among its private carrier members averaged only 15 percent from 2005 through 2022.

Observed over long timeframes, these are marked differences in turnover rates within long-distance trucking. Furthermore, it is revealing that during the depths of the Great Recession, during 2009 and 2010, when blue collar job openings were generally scarce, the annualized turnover rate for large and small TL carriers was still relatively high at 39 percent and 35 percent, respectively (see Figure 4-1). After the recession (starting in the third quarter of 2012), annualized turnover rates among TL carriers rose

___________________

4 ATA does not report how many carriers are included in the survey or how many employees work at the responding carriers. Accordingly, this is a self-selected sample of unknown representativeness. Despite these limits, the survey provides the only long-running data on driver turnover specifically in for-hire trucking, and it is a basis for most industry and policymaker discussions of the issue.

5 Because long-distance LTL carriers maintain a network of local terminals, they also employ local drivers. Linehaul LTL drivers are LTL employees that primarily haul trailers between the carrier’s terminals.

6 Benchmarking Report – National Private Truck Council. See www.nptc.org/benchmarking/benchmarking-report.

SOURCE: Burks et al. 2023.

sharply to 106 percent and 94 percent for large and small carriers, respectively. The rates then held steady for some time. Thus, although the deep recession muted the high turnover situation in the TL sector, traditionally high turnover rates returned during the recovery, while the comparison LTL and private fleet sectors continued to have lower and more stable rates.

The observed high driver turnover rates in the long-distance TL sector, which have been exhibited over long periods including during economic expansions and contractions, suggest that turnover is a structural feature of the sector. Warranting explanation, therefore, is why this structural feature persists given the drawbacks associated with high rates of driver turnover, including the constant need for carriers to recruit and train. Indeed, some prior studies have suggested that the nature of competition in the TL sector, which is fundamentally based on the supply of low-cost service, is at the root of the turnover problem (Burks et al. 2008; Monaco and Burks 2010).

Three features of the TL industry make cost competition strategically important for carriers to obtain business. First, there are low barriers to entry for providing TL service, because a lone driver leasing a power unit can start a new service with limited capital investment. Second, robust low-bid electronic auction markets for TL freight (especially dry van) suggest that the differentiation and branding of service has limited impact on the pricing of TL transportation, which benefits smaller carriers and new entrants competing for loads (Caplice 2007, 2021; Scott et al. 2017; Pickett 2018; Scott 2018; Acocella et al. 2020; Acocella and Caplice 2023). Third, the distribution of carrier sizes—only a few dozen very large carriers but

hundreds of medium-sized carriers and tens of thousands of very small carriers—suggests that average costs are similar for equivalent services, allowing carriers of different sizes to coexist over the long term and serve the same markets.7 Together, these features make long-distance TL service close to what economists call a “perfectly competitive” enterprise, for which cost minimization is a central survival strategy (Bernanke et al. 2021).8

A related consideration is that when TL carriers compete on low price, they must make tradeoffs among different costs to manage their total costs. To be sure, high rates of driver turnover do create costs, as the carrier must incur expenses to recruit and train new drivers while experiencing lower productivity and higher crash risk from the new drivers while they gain experience behind the wheel. To reduce these turnover costs and retain drivers, the carrier may choose to pay a driver more than the worker’s next best earning opportunity. Labor economists call higher pay used to offset undesirable working conditions a “compensating differential.” When compensating differentials are high enough, the carrier can reduce quits, even if TL working conditions are tough. The higher pay, however, will raise the carrier’s cost structure, possibly by more than any resulting savings in turnover costs.

A third option is to reduce the efficiency of driver dispatching. Although this may seem counterintuitive at first, a dispatching system that is intensely focused on the efficient positioning of drivers, such as by sending drivers to the load that is nearest their last drop-off location irrespective of proximity to the driver’s home base, can cause drivers to be sent far and wide across the carrier’s operational area. This practice can increase the likelihood that a driver will quit. Adjusting dispatching to allow drivers to be routed in the direction of home more often and more regularly and to operate in more familiar service areas will improve overall working conditions. This practice would facilitate recruitment and entice more drivers to stay on the job. Doing so, however, may make dispatching less efficient and less profitable, as revenue decreases due to missed loads and costs increase due to more empty trailers and out-of-route miles for which the carrier is not paid. Here again, the TL carrier must make a choice between overall cost savings and revenue maximization.

In seeking to explain why the economics of the long-distance TL sector can make high driver turnover a structural feature, Burks et al. (2023)

___________________

7 “Similar costs for equivalent services” implies that the average costs for moving a load from point A to point B are roughly similar for all well-managed firms. While large firms can offer more trucks and logistics functions, third party logistics companies which subcontract with multiple small carriers also compete at this level.

8 In the case of larger carriers where some modest product differences may exist, monopolistic competition with a large elasticity of substitution across firms gives similar results (Holmes and Stevens 2014).

have advanced a model of long-distance TL costs that embodies these three cost tradeoffs. The model assumes that drivers want enough work to have adequate earnings, but not so much that they do not get regular home time. Thus, drivers are assumed to be more likely to quit at any given level of pay as their home time and earnings vary from preferred levels, either because they do not get enough work (as in a freight market downturn) or they get too much work (as in a freight market upturn). In applying the model, the authors find that a typical long-distance TL carrier will tend to favor the cost-minimizing choices of an intense, efficient dispatching practice and controlling driver pay expenses while accepting the costs associated with the resulting high turnover. Although actions to lower turnover rates can produce savings in turnover-related costs, the costs associated with reducing high turnover to much lower levels can be high (in terms of higher payrolls, lower revenue, and the higher costs of getting drivers home regularly) and disadvantageous to the point that it is less costly to simply accept high driver turnover.

A real-world outcome that is sometimes offered as an illustration of this cost calculus is the decision in 1997 by J.B. Hunt, then the country’s the second largest long-distance TL carrier, to increase its mileage-based pay rate by 35 percent and hire only experienced drivers. Having experienced persistent annualized driver turnover rates of nearly 90 percent, the carrier expected that its higher payroll costs would be recouped by lower costs from fewer crashes and lower driver recruitment and training costs. Yet, although there was evidence that crash rates and turnover rates were both cut approximately in half (e.g., Belzer et al. 2002; Rodriguez et al. 2003, 2006), within 5 years this large TL carrier had reverted back to the lower starting pay rates that were in effect when turnover rates were high.

None of this means that long-distance TL carriers do not try to reduce driver turnover, and indeed there are any number of vendors willing to offer advice for doing so. It does imply, however, that carriers focused solely on cost competition must be willing to accept turnover costs when they result in savings in other costs that keep them competitive.9

ASSERTIONS OF CHRONIC DRIVER SHORTAGES

Many long-distance TL carriers believe there is a chronic shortage of drivers available to work for them and that this shortage, in turn, may contribute to the sector’s persistently high rates of driver turnover. For instance, since

___________________

9 Another way to make this point is that firms can choose their position in the competitive landscape, and this can mean turnover rates vary across firms. But the competitive structure of long-distance TL operations is a fact of economic life to which individual firms must adapt, and the evidence suggests that making long-distance TL turnover rates as low as those of LTL and private carrier operations generally is not feasible.

2005, the American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI), a non-profit research group associated with ATA, has surveyed carriers on the top policy and economic issues facing the industry. In 2005, the driver shortage was ranked second among issues of concern among the more than 2,000 carriers surveyed (ATRI 2005). In 2023, more than 4,000 industry participants responded to the survey and the driver shortage was again ranked second among issues (ATRI 2023). In other intervening years, the concern had been ranked as high as number 1 but always in the top 10. Meanwhile, the ATA has sponsored multiple studies raising concerns about driver shortages, dating back to at least 1987, and the most recent was in 2022. A listing of the studies and reports is provided in Table 4A-2 of the chapter addendum. It merits noting that ATA has repeatedly emphasized that the asserted shortage is mostly confined to the long-distance TL sector (Costello 2019).

Because the ATA’s studies have been conducted using proprietary techniques and assumptions that are not publicly defined, it is not possible to evaluate the validity of their claims of driver shortages. However, those claims are subject to, as a general matter, the basic economic principles of supply and demand. Notably, labor economists maintain that when demand for workers in an occupation increases, the normal response is to increase wages. The implication is that, in the absence of significant lag-caused friction in this process, higher wages should promptly yield a higher supply of labor (e.g., Arrow and Capron 1959). If there is friction, such as a lengthy time required to train and credential workers, a labor shortage may result that extends beyond the short-term. In the case of long-distance truck driving, however, such friction would seem to be minimal and short-lived, as most training and credentialling courses for the Class A Commercial Driver’s License needed to work in heavy-duty trucking take only about 6 to 7 weeks of full‐time instruction and practice. Thus, although there may be lags in the response of the supply of drivers to higher wages, one would expect the lags to be on the order of several months, not the several years suggested by the trucking industry surveys and cited studies.

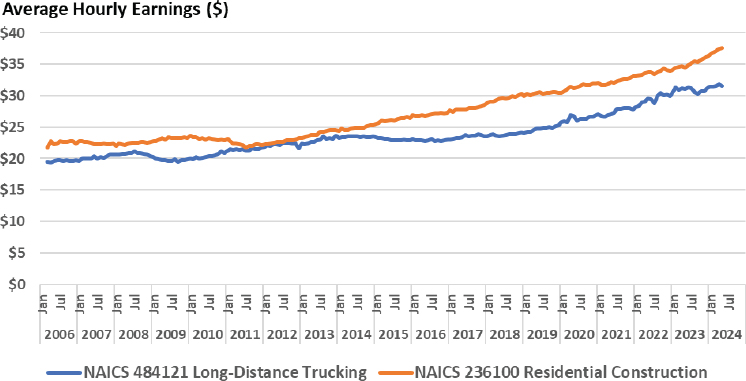

Labor economists also maintain that one observable signal of a labor shortage is an increase in the earnings of the occupation experiencing the shortage relative to the earnings of workers in other occupations requiring similar human capital (e.g., level and types of education) (Blank and Stigler 1957). A shortage that leads to higher wages in one occupation should entice workers in these other comparable occupations to enter the occupation experiencing a shortage, thereby closing the wage differential. Therefore, a chronic shortage would be expected to result in a wage differential that persists among occupations. In this regard, a relevant place to look for similar occupations, given the findings of Burks and Monaco (2019) and Phares and Balthrop (2022), is residential construction.10 Figure 4-2 compares BLS

___________________

10 ATA’s 2005 driver shortage study that has more details about methodology than later versions, makes the same suggestion (Global Insight Inc. 2005).

NOTES: Data are seasonably adjusted and earnings are in current dollars. NAICS = North American Industrial Classification System.

SOURCE: Committee generated from Current Employment Statistics, Bureau of Labor Statistics, www.bls.gov/ces.

data on hourly wage trends for all employees in the long-distance TL sector (data on drivers alone are not available) with trends for all employees in residential building construction. These comparisons show that wages in residential construction nearly converged with wages in the TL sector during the housing construction downturn after the Great Recession, and they then diverged again. Significantly, the average wage for all employees in residential construction remained above the prevailing wage in the long-distance TL sector over the full period of that study.11 These trends are not indicative of the wage premium one would expect for long-distance TL employees if they were indeed working in an occupation experiencing a chronic labor shortage.

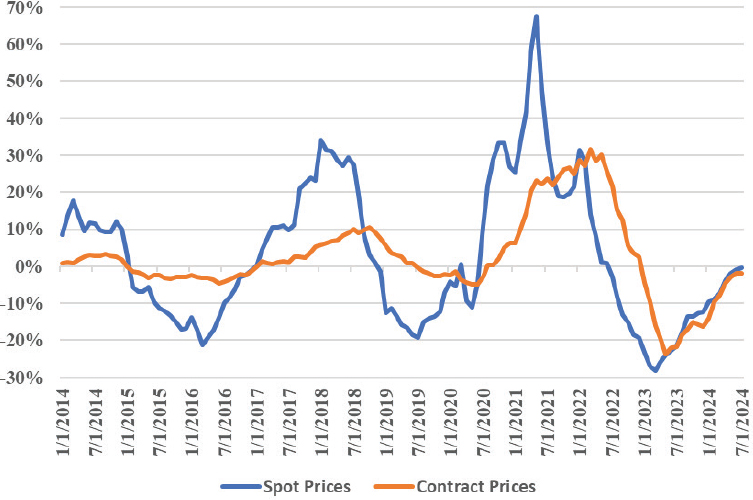

Finally, another way to examine claims of chronic driver shortages is by looking for lags in the supply of long-distance TL service relative to the demand for service. The supply of long-distance TL service depends on the amount of capacity available at any point in time, and that capacity is provided by firms having both trucks and drivers. Thus, when the demand for long-distance TL service is rising rapidly, freight rates should increase

___________________

11 Burks and Monaco (2019) found average annual earnings of all heavy and tractor-trailer truck drivers to be somewhat higher than other blue-collar workers, but in Figure 4-2 the comparison is for hourly wages. Annual earnings of drivers may well be relatively high because of their tendency to work long hours.

to attract more capacity, albeit with a possible lag. In this regard, there are observable service price indicators of shortages in capacity, including spot prices in short-term auction markets and prices for longer-term service contracts (Caplice 2007, 2021; Scott et al. 2017; Pickett 2018; Scott 2018; Acocella et al. 2020; Acocella and Caplice 2023). Spot market rates can be quite volatile, suggesting immediate levels of excess demand or excess supply, while contract rates reveal broader based, but slower, signals of the balance of demand and supply. Thus, a spike in spot rates implies a short-term shortage in long-distance TL capacity, which implies a short-term shortage of drivers, trucks, or both. Alternatively, when broadly based but slower-moving contract rates are rising, this could mean that the shortage of capacity, including drivers and trucks, persists.

Figure 4-3 illustrates the recent pattern of long-distance TL spot and contract rates for the period 2014 to mid-2024. In both markets, periods of increasing rates are routinely followed by periods of decreasing rates, consistent with increases in service capacity and/or decreases in the demand for service. This pattern held true during the pandemic shutdown and recovery (2020 to 2022), albeit with a very large spike in demand that was reflected in higher spot and contract rates, which was then followed by a large drop in rates in response to falling demand. An important implication is that when spot rates fall below the slower-moving contract rates, there is excess capacity. This implies an excess supply of trucks and drivers in the long-distance TL sector. Thus, although spot and contract price changes may be indicative of driver shortages and surpluses, the shortages and surpluses are resolved, albeit with time lags, through the operation of normal market processes without suggesting that driver shortages are a chronic problem.

The application of traditional economic principles, therefore, does not support assertions of persistent shortages of drivers in the long-distance TL sector. Furthermore, the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, whose members include both drivers and small companies that employ drivers, also does not support this claim (Schremmer 2021; Overdrive 2023).12 What seems likely, in the committee’s view, is that carriers in the long-distance TL sector have come to believe there are chronic shortages of drivers because of the constant need to replace them during both expansions and contractions of the long-distance TL sector. However, that need, as evidenced by the research and data presented, may be explained by the overall effect of the industry’s competitive structure, which compels carriers to employ cost-focused managerial strategies.

___________________

12 In presentations to the study committee, the owner-operator driver trade group dismissed claims that there is a long-term shortage of drivers in the United States.

NOTES: Spot market price changes are represented by publicly released data from DAT Freight and Analytics, www.dat.com/trendlines/van/national-rates. Contract price changes are represented by the BLS producer price index for general freight trucking, long-distance, truckload primary services, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PCU484121484121P.

SUMMARY POINTS

- The academic literature suggests an array of factors are associated with a driver’s decision to quit the industry altogether or to leave the employment of a particular TL carrier, including carrier-controlled factors (such as dispatchers who work effectively with drivers) and cyclical factors beyond the control of a single carrier. Findings also indicate that working conditions are associated with long-distance TL driver turnover and retention. Long-distance TL drivers tend to have highly irregular work schedules, work long hours per week, and have uncertain and limited time at home. Variability in weekly pay due to irregular work combines with the challenges that arise from erratic schedules to create what drivers perceive to be tough working conditions for only moderate pay, which is a combination conducive to high driver turnover.

- The high rates of driver turnover in the long-distance TL sector, observed over long periods, suggests that high turnover at the carrier level is a structural feature of the sector that compels each carrier to engage in certain practices conducive to turnover. This structural feature stems from the highly competitive nature of the TL business. Long-distance TL service is provided in the manner of a commodity, in that the sector is characterized by numerous suppliers with little evidence of economies of scale. Carriers must compete based on low cost and low price, rather than by differentiating their brands and services to enable premium rates for covering higher costs. Carriers focused on cost competition find they must accept expenses associated with driver turnover when the resulting cost savings from strictly controlling the cost of other inputs that may contribute to turnover, such as by paying drivers a defined amount per load rather than paying them for hours worked that can be variable, will lead to even lower costs and keep the business competitive.

- Many long-distance TL carriers believe there is a chronic shortage of drivers available to work in their business and that this shortage, in turn, may be contributing to the sector’s persistently high rates of driver turnover. Although these claims do not hold up to economic scrutiny, carriers in the long-distance TL sector may have come to believe them because of the constant need to replace drivers.

ADDENDUM

TABLE 4A-1 Studies of Driver Turnover in the Long-Distance Truckload Sector

| Citation | Sample and Data | Dependent Variable | Variables of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corsi and Martin (1982) | Multi-wave survey of ~500 term and trip-leased owner-operators in winter of 1978 (323 and 156 responses to the first survey from term- and trip-leased owner-operators, respectively); second survey 1 year later that received 287 and 139 term- and trip-leased responses. | Whether owner-operators exited from the trucking industry. |

|

| Beilock and Capelle (1990)a | Survey of drivers who were outbound from the Florida Peninsula in 1988. Usable sample of N = 878 drivers. | Intentions to stay in trucking (i.e., intentions to exit the industry). |

|

| Lemay et al. (1993)a | Survey of 650 CEOs of members of the Interstate Truckload Carriers Conference of the American Trucking Associations. N = 175 responses received from carriers that were not independent owner-operators. | Carrier-level turnover rates reported as a range, not a specific figure. |

|

| Citation | Sample and Data | Dependent Variable | Variables of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richard et al. (1995)a | Survey of 1,500 irregular route truck drivers working for one large truckload carrier. N = 402 usable responses received. | Drivers’ intention to leave their current carrier. |

|

| Stephenson and Fox (1996)a | Survey of 2,256 sent out to drivers from 57 motor carriers. N = 1,791 usable surveys received, with 1,464 employee drivers and 291 contract owner-operators responding. | Asked about factors that are important for retention needs for their current carrier. |

|

| Shaw et al. (1998)a | Survey of 1,072 motor carriers with at least 30 employees identified from the 1993–1994 TTS Blue Book of Trucking Companies. N = 227 complete surveys were received. | Voluntary driver turnover rates (quit rate) and driver discharge rates (dismissal rate). |

|

| Citation | Sample and Data | Dependent Variable | Variables of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keller and Ozment (1999a)a | Survey of 222 dispatchers at 5 large TL motor carriers, resulting in N = 149 usable responses. | Dispatcher-level annualized driver turnover rate. |

|

| Keller and Ozment (1999b)a | Survey of 222 dispatchers at 5 large TL motor carriers, resulting in N = 149 usable responses. | Dispatcher-level monthly voluntary driver turnover rate. |

|

| Keller (2002)a | Survey of 222 dispatchers at 5 large TL motor carriers, resulting in N = 149 usable responses. | Dispatcher-level annualized driver turnover rate. |

|

| Min and Lambert (2002)a | Survey of 3,000 randomly selected motor carriers listed in the 1999 Motor Carrier Directory and located in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Georgia. N = 422 usable responses were received. | Annual voluntary driver turnover rate. |

|

| Min and Emam (2003)a | Survey of 3,000 randomly selected motor carriers listed in the 1999 Motor Carrier Directory and located in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Georgia. N = 422 usable responses were received. | Annual voluntary driver turnover rate. |

|

| Citation | Sample and Data | Dependent Variable | Variables of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| de Croon et al. (2004)a | Surveys sent in September 1998 to 2,000 truck drivers in the Netherlands. Of these, 1,225 surveys were returned. In September 2000, the 1,225 first wave responders were surveyed again, resulting in 820 surveys. 137 drivers were excluded due to retirement, dismissal, or incomplete data, resulting in N = 683. | Whether driver voluntarily left their job in the prior 2 years. |

|

| Morrowzuki et al. (2005)a | Survey sent to 724 drivers working for a medium-sized Midwestern TL motor carrier in December 2002. N = 207 usable responses received. | Observed voluntary turnover based on whether drivers left company by December 31, 2003. |

|

| Burks et al. (2006)a | Archival weekly data for more than 5,000 drivers who were hired by a large TL motor carrier from September 1, 2001, to March 31, 2005. | Whether a driver quit or was dismissed during a given week. |

|

| Citation | Sample and Data | Dependent Variable | Variables of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Garver et al. (2008)a | Survey sent to 2,003 drivers that worked for one irregular route TL carrier. N = 431 usable responses received. | Drivers’ intention to stay with the carrier. |

|

| Burks et al. (2009) | Data collected in person from 1,065 new to the industry trainee drivers, operational data on same for up to 2 years. | Driver’s exit from firm during a 1-year period required to pay off training debt. |

|

| Suzuki et al. (2009)a | Archival weekly data for 971 drivers for one TL motor carrier over a 9-month period and archival weekly data for 5,106 drivers for a 12-month period from a second motor carrier. | Whether a driver quit the carrier on a given week. |

|

| Taylor et al. (2010)a | Survey of 320 contract owner-operators with exclusive leases to one specialized, long-haul, irregular route TL motor carrier. N = 214 usable responses received. | Drivers’ intention to stay with the carrier. |

|

| Williams et al. (2011)a | Survey sent to 800 truck drivers working for a privately held transportation and logistics company. N = 197 usable surveys were obtained. | Multidimensional scaling to ask informants most and least important attributes affecting retention decision. |

|

| Citation | Sample and Data | Dependent Variable | Variables of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cantor et al. (2011)a | Survey distributed in Q4 2008 and Q1 2009 to 1,919 drivers through a sponsoring organization. N = 604 surveys returned. | Drivers’ intention to quit the carrier and the industry. |

|

| Kettinger et al. (2012)a | Survey of 700 truck drivers working for a large intermodal company. N = 140. | Drivers’ intention to quit the carrier he/she works for. |

|

| Kemp et al. (2013)a | Surveys distributed to N = 435 truck drivers at 7 truck stops in the United States. | Drivers’ commitment to their current employer. |

|

| Schulz et al. (2014)a | Surveys distributed to truck drivers at two international trucking companies, resulting in N = 251 participants. | Drivers’ intention to quit the carrier he/she works for. |

|

| Burks et al. (2015) | Data for all driver applicants from a large truckload carrier from 2003–2009; additional data on a subset of ~900 hires from 2005–2006 concerning cognitive and noncognitive abilities; employee referral program from October 2007–December 2009. Data from N = 628 drivers ultimately used. | Whether a driver quits a carrier during a worker x week level of observation. |

|

| Prockl et al. (2017)a | Survey of 1,058 truck drivers in Germany, resulting in N = 143 usable responses. | Drivers’ retention proneness. |

|

| Citation | Sample and Data | Dependent Variable | Variables of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hoffman and Burks (2017) | N >5,000 new inexperienced drivers across 5 driver training schools run by a large truckload carrier from 2002–2009. | Whether the driver quits a carrier. |

|

| Miller et al. (2021) | Annualized driver turnover rates for large (>$30 million in annual revenue) truckload carriers from the American Trucking Associations from Q1 2006–Q4 2018. | Year-over-year change in the annualized rate of turnover at large truckload carriers for that quarter. |

|

| Conroy et al. (2022) | 34 weeks of data for N = 14,898 truck drivers working for a single large truckload carrier. | Occurrence of a voluntary turnover event in the weekly level for a driver that the carrier viewed as a negative event. |

|

a Adapted from Miller et al. 2021.

NOTE: CEO = chief executive officer; EOBR = electric on-board recorder; IT = information technology; LTL = less than truckload; TL = truckload.

TABLE 4A-2 Industry Reports and Studies Asserting Persistent Truck Driver Shortages

| Title | Source | Author and Date |

|---|---|---|

| An Assessment of the Truck Driver Shortage | ATA Statistical Analysis Department | Casey (1987) |

| Empty Seats and Musical Chairs: Critical Success Factors in Truck Driver Retention | Gallup Organization | Christenson et al. (1997) |

| The US Truck Driver Shortage: Analysis and Forecasts | Global Insight | Global Insight Inc. (2005) |

| Truck Driver Shortage Update | ATA | Costello (2012) |

| Truck Driver Shortage Analysis 2015 | ATA | Costello and Suarez (2015) |

| Truck Driver Shortage Analysis 2017 | ATA | Costello (2017) |

| Truck Driver Shortage Analysis 2019 | ATA | Costello and Karickhoff (2019) |

| Driver Shortage Update 2021 | ATA Economics Department | American Trucking Associations (2021) |

| Driver Shortage Update 2022 | ATA Economics Department | American Trucking Associations (2022) |

REFERENCES

Acocella, A., and Caplice, C. (2023). Research on truckload transportation procurement: A review, framework, and future research agenda. Journal of Business Logistics, 44(2), 228–256.

Acocella, A., Caplice, C., et al. (2020). Elephants or goldfish?: An empirical analysis of carrier reciprocity in dynamic freight markets. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 142, 102073.

Arrow, K. J., and Capron, W. M. (1959). Dynamic shortages and price rises: The engineer-scientist case. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 73(2), 292–308.

American Trucking Associations, Economics Department. (2021). Driver shortage update 2021. Washington, DC: American Trucking Associations.

American Trucking Associations, Economics Department. (2022). Driver shortage update 2022. Washington, DC: American Trucking Associations.

American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI). (2005). Top industry issues 2005. ATRI Research Reports. Arlington, VA: American Transportation Research Institute.

American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI). (2023). Top industry issues 2023. ATRI Research Reports. Arlington, VA: American Transportation Research Institute.

Belman, D. L., Monaco, K., et al. (2004). Sailors of the concrete sea: A portrait of truck drivers’ work and lives. Michigan State University Press.

Belzer, M. H., Rodriguez, D., et al. (2002). Paying for safety: An economic analysis of the effect of compensation on truck driver safety. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration.

Bernanke, B., Frank, R., et al. (2021). Principles of economics. McGraw-Hill.

Blank, D. M., and Stigler, G. J. (1957). The demand and supply of scientific personnel. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Burks, S. V., and Monaco, K. (2019). Is the U.S. labor market for truck drivers broken? Monthly Labor Review (Featured Article: March).

Burks, S., Saager, K., et al. (2006). The impact of tenure, experience, and type of work on the turnover of newly hired drivers at a large truckload motor carrier. National Urban Freight Conference. Long Beach, CA.

Burks, S. V., Carpenter, J., et al. (2008). Using behavioral economic field experiments at a firm: The context and design of the truckers and turnover project. In S. Bender, J. Lane, K. Shaw, F. Andersson, and T. von Wachter (Eds.), The analysis of firms and employees: Quantitative and qualitative approaches (pp. 45–106). University of Chicago Press.

Burks, S. V., Carpenter, J., et al. (2009). Cognitive skills affect economic preferences, social awareness, and job attachment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(19), 7745–7750.

Burks, S. V., Cowgill, B., et al. (2015). The value of hiring through employee referrals. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(2), 805–839.

Burks, S. V., Kildegaard, A., et al. (2023). When is high turnover cheaper? A simple model of cost tradeoffs in a long-distance truckload motor carrier, with empirical evidence and policy implications. Institute of Labor Economics (IZA) Discussion Papers, 16477, 58.

Caplice, C. (2007). Electronic markets for truckload transportation. Production and Operations Management, 16(4), 423–436.

Caplice, C. (2021). Reducing uncertainty in freight transportation procurement. Journal of Supply Chain Management, Logistics and Procurement, 4(2), 137–155.

Casey, J. F. (1987). An assessment of the truck driver shortage. Statistical Analysis Department. Arlington, VA: American Trucking Associations.

Chen, G. X., Sieber, W. K., et al. (2015). NIOSH national survey of long-haul truck drivers: Injury and safety. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 85, 66–72.

Christenson, D., Aames, R., et al. (1997). Empty seats and musical chairs: Critical success factors in truck driver retention. Gallup Organization for the ATA Foundation.

Coker, A. (2022, April 29). Driver turnover driven by different factors depending on tenure, gender. FreightWaves News-Recruiting Rundown-Sponsored Insights-Trucking. https://www.freightwaves.com/news/driver-turnover-driven-by-different-factors-depending-on-tenure-gender.

Conroy, S. A., Roumpi, D., et al. (2022). Pay volatility and employee turnover in the trucking industry. Journal of Management, 48(3), 605–629.

Costello, B. (2012). Truck driver shortage update. Arlington, VA: American Trucking Associations.

Costello, B. (2017). Truck driver shortage analysis 2017. Alexandria, VA: American Trucking Associations.

Costello, B. (2019). ATA statement on flaws in Bureau of Labor Statistics’ driver shortage article. Arlington, VA: American Trucking Associations.

Costello, B., and Karickhoff, A. (2019). Truck driver shortage analysis 2019. Arlington, VA: American Trucking Associations.

Costello, B., and Suarez, R. (2015). Truck driver shortage analysis 2015. Arlington, VA: American Trucking Associations.

Garver, M. S., Williams, Z., et al. (2008). Employing latent class regression analysis to examine logistics theory: An application of truck driver retention. Journal of Business Logistics, 29(2), 233–257.

Global Insight Inc. (2005). The US truck driver shortage: Analysis and forecasts. Lexington, MA: American Trucking Associations.

Holmes, T. J., and Stevens, J. J. (2014). An alternative theory of the plant size distribution, with geography and intra-and international trade. Journal of Political Economy, 122(2), 369–421.

Kambourov, G., and Manovskii, I. (2008). Rising occupational and industry mobility in the United States: 1968–97. International Economic Review, 49(1), 41–79.

Keller, S. B., and Ozment, J. (1998). Managing driver retention: Effects of the dispatcher. Department of Business Logistics, The Pennsylvania State University.

Keller, S. B., and Ozment, J. (1999a). Exploring dispatcher characteristics and their effect on driver retention. Transportation Journal, 39(1), 20–33.

Keller, S. B., and Ozment, J. (1999b). Managing driver retention: Effects of the dispatcher. Journal of Business Logistics, 20(2), 97–108.

Kuder, J. (2022). Avatar Fleet blog: Top 5 reasons why truck drivers quit your company. https://www.avatarfleet.com/blog/reasons-truck-drivers-quit.

Li, M., Bolumole, Y. A., et al. (2022). Antecedents of spot and contract freight mix in the truckload sector. Transportation Journal, 61(4), 331–368.

Miller, J. W., Bolumole, Y., et al. (2021). Exploring longitudinal industry-level large truckload driver turnover. Journal of Business Logistics, 42(4), 428–450.

Monaco, K., and Burks, S. V. (2010). Chapter 8. Trucking. In L. Hoel, G. Giuliano, and M. Meyer (Eds.), Intermodal freight transportation: Moving freight in a global economy (pp. 145–164). Eno Transportation Foundation.

National Private Truck Council (NPTC). (2023). 2023 National Private Truck Council benchmarking survey report. https://www.nptc.org/benchmarking/benchmarking-report.

Overdrive. (2023). ATA’s “driver shortage” refuted by … ATA. Overdrive. https://landline.media/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Driver-Shortage-1-Pager-Final-1.pdf.

Phares, J., and Balthrop, A. (2022). Investigating the role of competing wage opportunities in truck driver occupational choice. Journal of Business Logistics, 43(2), 265–289.

Pickett, C. (2018). Navigating the US truckload capacity cycle: Where are freight rates headed and why? Journal of Supply Chain Management, Logistics and Procurement, 1(1), 57–74.

Powell, W. B., Sheffi, Y., et al. (1988). Maximizing profits for North American Van Lines’ truckload division: A new framework for pricing and operations. Interfaces, 18(1), 21–41.

Ricks, E. (2020, July 15). Reducing driver turnover. FreightWaves Daily Infographic.

Rodriguez, D. A., Rocha, M., et al. (2003). The effects of truck driver wages and working conditions on highway safety: A case study. Transportation Research Record, 1833, 95–102.

Rodriguez, D. A., Targa, F., et al. (2006). Pay incentives and truck driver safety: A case study. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 59(2), 205–225.

Schremmer, M. (2021, July). The truth about the driver shortage (Psst … There isn’t one). Land Line Now. https://landline.media/article/the-truth-about-truck-driver-shortage.

Scott, A. (2018). Carrier bidding behavior in truckload spot auctions. Journal of Business Logistics, 39(4), 267–281.

Scott, A., Parker, C., et al. (2017). Service refusals in supply chains: Drivers and deterrents of freight rejection. Transportation Science, 51(4), 1086–1101.

Suzuki, Y., Crum, M. R., et al. (2009). Predicting truck driver turnover. Transportation Research Part E, 45(4), 538–550.

Viscelli, S. (2016). The big rig: Trucking and the decline of the American dream. University of California Press.

Williams, Z., Garver, M. S., et al. (2011). Understanding truck driver need-based segments: Creating a strategy for retention. Journal of Business Logistics, 32(2), 194–208.