Pay and Working Conditions in the Long-Distance Truck and Bus Industries: Assessing for Effects on Driver Safety and Retention (2024)

Chapter: 3 Compensation Methods, Incentives, and Working Conditions in Long-Distance Trucking

3

Compensation Methods, Incentives, and Working Conditions in Long-Distance Trucking

Chapter 2 distinguishes drivers of tractor-trailer trucks operating locally from those operating over long distances. Local drivers typically operate within 150 miles of their home base, such as for private carriage and container drayage.1 The long-distance drivers that are the focus of this study work in the for-hire truckload (TL) sector, including general freight and specialized services. This chapter reviews the usual work tasks of a long-distance TL driver and discusses in more detail the three different types of carrier-driver relationships: (a) independent owner-operators, (b) leased-on owner-operators, and (c) employee drivers. The types of compensation used in the for-hire long-distance TL sector are described, distinguishing between piece-rate forms (such as pay per load moved, pay per load-mile, and pay as a percentage of the revenue generated from a transported load) and non-piece-rate forms (such as hourly pay and salary). A key difference is that a driver who is paid piece rate receives a predetermined, fixed amount for the movement of a load. This is not the case for a driver paid by the hour, where the pay earned to move a load will vary depending on time spent driving, or on a salary, where earnings are independent of loads moved.

The chapter also reviews the reasons that for-hire long-distance TL carriers tend to use piece-rate methods. The discussion makes a crucial point that nearly all drivers in this sector work for some form of piece-rate pay, while the few drivers who do not are usually doing distinctly different work

___________________

1 Drayage typically involves the movement of a domestic or international container between a marine port or rail terminal and a warehouse or distribution center. These TL moves are usually for distances of 150 miles or less.

or are different types of drivers than the preponderance earning piece-rate pay. The reason this point is crucial is that the for-hire long-distance TL sector, having working conditions that are distinct from all other trucking sectors, lacks a significant group of drivers who earn non-piece-rate pay to allow for alternative pay methods to be tested for differential effects. This situation greatly complicates efforts to understand the safety effects of alternative compensation methods, as will be explained further in Chapter 5. It suggests too that the availability of compensation data per se is not the fundamental challenge. Even if researchers could gain access to the proprietary compensation records of for-hire long-distance TL carriers, the data would be for piece-rate work almost exclusively.

DRIVER TASKS IN THE TRUCKLOAD SECTOR

The relationship between for-hire long-distance TL carriers and their drivers starts, of course, with the fundamental task of operating a tractor-trailer truck. This work involves driving to the shipper’s location, acquiring the shipment (either by hooking onto an already-loaded trailer or by “live-loading” a trailer with the shipment), and then driving the tractor-trailer combination from that location to the consignee or receiver. At the destination, the trailer is either unloaded, switched for an empty trailer, or the tractor leaves without a trailer (“bobtailing”). The driver will then head to another shipper’s location (“deadheading”) to obtain a load or return home.

This transportation work is done in the time frame required by the shippers and receivers tendering the loads, and involves many attendant tasks (Gittleman and Monaco 2020).2 The tasks include interacting with employees of the shipper and receiver, assuring the security of the freight, and sometimes personally loading or unloading the cargo, especially for specialized haulage. Drivers are required to inspect the condition of their equipment, verify that the total weight and weight distribution of the load is within legal requirements, and select the best route to use when accounting for factors such as fuel and rest stops, truck prohibitions and bridge restrictions, tolls, and anticipated traffic congestion and weather conditions. Drivers must also record work hours according to the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s (FMCSA’s) hours of service (HOS) regulations

In addition to these tasks, which are standard for drivers who are directly employed by long-distance TL carriers, a driver who is also an

___________________

2 Gittleman and Monaco (2020) use data from the Occupational Requirement Survey of the Bureau of Labor Statistics for the occupation of heavy and tractor-trailer truck driver (Standard Occupation Code 53-3032) to create a nationally representative picture of the tasks and job requirements of a heavy-duty truck driver. Most of these are relevant to the work of long-distance TL drivers.

owner-operator will have other work tasks. As both driver and proprietor of a trucking business, an owner-operator must also acquire and maintain the truck tractor and possibly the semi-trailer that is regularly used. The owner-operator will be expected to satisfy numerous legal, regulatory, and financial conditions. Also, as discussed next in explaining driver-carrier relationships, the owner-operator may have the responsibility to acquire the loads to be moved and to negotiate with shippers and freight brokers about the service price.

TYPES OF DRIVER-CARRIER RELATIONSHIPS

As explained in Chapter 2, carriers in the for-hire long-distance TL sector range widely in size and will often compete with other carriers for the same business irrespective of their relative sizes. The smallest carriers have a single truck and possibly a semi-trailer, while the largest have fleets consisting of tens of thousands of trucks and semi-trailers. The smallest carriers are owner-operators, who also serve as drivers. The largest carriers will usually employ drivers directly, but they may also supplement this workforce with leased-on owner-operators. More details on each type of driver and driver-carrier relationship, starting with the varied roles of owner-operators, are provided next.

For-Hire Owner-Operators

For-hire owner-operators are individuals who own their own equipment and are themselves TL carriers because they have their own operating authority (i.e., an FMCSA issued MC number).3 Independent owner-operators have full control over their operations, so they must obtain their own freight from shippers and freight brokers. While some owner-operators have pre-negotiated arrangements with shippers and brokers specifying prices for loads, they may also obtain business from “load boards.” Load board shipments are priced on a spot market basis using reverse auctions. In a reverse auction, carriers sequentially offer lower and lower prices until one is accepted by the shipper (Caplice 2021; Acocella and Caplice 2023).

Whether negotiated or spot-market, the rates TL carriers obtain tend to be related to a significant degree to the distance that a load must be transported. Accordingly, owner-operators receive their revenue on what is essentially a piece-rate basis; that is, load by load with prices established in accordance with miles associated with the shipment or the door-to-door

___________________

3 The trucks can be owned outright or have bank loans to support financing. As explained by Viscelli (2016), for-hire owner-operators with more experience and time in business are more likely to own their trucks outright.

distance.4 For instance, if an owner-operator agrees to a freight rate of $2.50 per mile, the rate must compensate for variable expenses such as fuel and maintenance in addition to the driver’s time. The rate must also contribute to the operator’s insurance, maintenance, and investment in equipment if the goal is to remain in business over time.

Regarding the work tasks identified above, some owner-operators in for-hire service will complete all of them, while others will hire other parties to do them. For instance, an owner-operator may hire or contract out for dispatching and customer service agents who handle communications with shippers and receivers. The owner-operator may also hire someone to solicit potential loads, if they are not working with freight brokers (agents whose business it is to match small carriers with shippers) or obtaining business from load boards or specific shippers. For-hire owner-operators are also responsible for all back-office activities, such as collecting payments from shippers and brokers, handling all associated paperwork, and paying their self-employment taxes (Viscelli 2016). The costs associated with these tasks must also be recouped from the revenue generated by the freight rates charged.

In this regard, therefore, the piece rate that an owner-operator obtains cannot be viewed as equivalent to the piece rate (pay per mile) that an employee driver receives because the former’s rate compensates for many costs in addition to driving time. In short, for-hire owner-operators have a great deal at stake in producing their piece-rate output, as they receive all revenue and must cover all fixed and incremental costs from the piece-rate payments for this output.

Leased-On Owner-Operators

Leased-on owner-operators are individuals who own their truck but contract their driving services to a carrier for a defined period. The leased-on owner-operator then drives under the legal operating authority of the carrier. Lease terms vary, based on whether the driver provides both the truck-tractor and semitrailer or just the truck-tractor. Leased-on owner-operators do not solicit their own freight, which is handled by the carrier, which can leverage marketing economies of scale and scope (Rakowski 1988).5 Hence, dispatchers working for the carrier offer loads to the leased-on owner-operator. Sometimes the truck is leased-on by the driver from the carrier through a lease-to-purchase agreement. In effect, the owner-operator leverages a

___________________

4 The miles are measured according to a standard mileage chart, as opposed to the number of miles that may actually be driven due to variations in routes taken.

5 A leased-on owner-operator is typically forbidden to solicit freight because this individual is operating only under the authority of a carrier, not the owner-operator’s own authority.

commitment to work as an independent contractor for a particular carrier to get the carrier to finance the purchase of a truck through a lease-to-own contract. Lease-purchase contracts can offer an economic opportunity to a driver who wants to become an owner-operator but who does not qualify for conventional financing to purchase a truck. For the carrier, this practice can also be a means for obtaining new drivers.6

Because leased-on drivers are legally considered to be independent contractors, carriers are limited in the extent to which they can exert control over the owner-operator’s work activities. For example, a leased-on owner-operator may be required to meet pick-up and delivery windows set by customers, but how the work is performed in the interim is at the discretion of the driver. Due to their contractor status, leased-on owner-operators can also resist installing technologies not mandated by regulation. In practice, however, this autonomy can be constrained. For instance, even though leased-on operators have the legal authority to reject a load offered by the carrier, they may be hesitant to do so out of concern that the carrier’s dispatchers will offer less desirable loads in the future (Baker and Hubbard 2004; Viscelli 2016).

Leasing arrangements confer several benefits on owner-operators. In contrast to for-hire owner-operators, the leased-on model reduces the driver’s administrative duties and allows the driver to shift some expenses to the carrier, but at the cost of reducing revenue. The leased-on driver can often obtain discounts on fuel and maintenance by leveraging programs offered by the carriers. Importantly, a large TL carrier will have the scale to justify being invited to a large shipper’s procurement auctions, allowing the carrier to strategically place bids to assemble a mix of loads that leverage the economies of scope inherent in truckload operations (Caplice 2007; Muir et al. 2019). As a result, the leased-on owner-operator can improve productivity through load-matching that leverages the carrier’s economies of scope.7

Three basic types of compensation are paid to leased-on owner-operators. All are variations of piece rates. One method is to provide a proportion of the revenue that the carrier receives for hauling the load.

___________________

6 FMCSA has established a task force to assess the fairness of these leasing arrangements and to identify and rectify exploitative practices such as burdensome repayment terms. Related concerns were also raised by the Consumer Protection Financial Bureau in its report “Consumer risks posed by employer-driven debt” (Office for Consumer Populations 2023). See www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/issue-spotlight-consumer-risksposed-by-employer-driven-debt/full-report.

7 Economies of scope exist when it is less costly to produce two or more outputs in the same production process than it would be to produce each separately. In long-distance TL operations each load from point A to point B is a product, so it is sensible that being able to have multiple loads in sequence that bring a driver back to his or her starting point (such as A to B, B to C, and then C to A) would be less costly than hauling each load with a different truck.

The compensation, for instance, might be equivalent to 65 percent of the revenue if the carrier leases only the owner-operator’s tractor in addition to driving services or it may be 75 percent if the carrier also leases the owner-operator’s semi-trailer. Thus, if a TL carrier receives the same $2.50 per mile for a tendered load as the for-hire owner-operator in the example above, the leased-on owner-operator would receive a fraction of the resulting fee for service that is billed to the shipper. Hence, the leased-on driver will not be compensated when traveling from a drop-off location to another location to obtain a load, which are not revenue-miles. A second method is payment on a per-mile basis with payment only for miles driven with a load. The rate paid would indirectly reflect the average revenue per mile that the carrier receives for loads. The third method is payment per mile that includes all miles operated at the direction of the carrier, regardless of whether loaded, empty, or bobtailing. In this case, the per-mile rate will usually be lower than when paid only for loaded miles.

Although all three of these compensation schemes—percentage-pay, pay-for-loaded miles, and pay-for-all-miles—are piece-rate they differ in the degree to which they reflect the level of risk borne by the owner-operator. For instance, a payment that is structured as a percentage of the freight bill shifts the benefit of a freight billing rate increase, and the cost of a rate decline, to the leased-on owner-operator (Viscelli 2016). It also shifts from the TL carrier to the owner-operator the risk of having to travel many miles empty to reposition equipment. Here again, the piece rate is not equivalent to the piece-rate pay that is received by employee drivers because it must cover costs incurred by the owner-operator in addition to the cost of the time spent driving.

Employee Drivers

Employee drivers operate vehicles owned by the carriers that employ them. Hiring an employee driver puts the output of freight services within the supervisory structure of the carrier. Consequently, drivers are subject to more extensive controls (e.g., heightened levels of monitoring), especially as it pertains to how work is performed (Levy 2023). For example, carriers are free to install on-board cameras that record the movements of employee drivers in the cab (although this could influence the rate of quits in a high-turnover setting as will be discussed in Chapter 4). Employee-drivers also are not able to reject loads that are tendered to them by the employer carrier (Baker and Hubbard 2004).8

___________________

8 At the same time, employee drivers and dispatchers may negotiate about tendered loads. For example, a dispatcher may ask a driver to take unattractive loads one week in return for a series of attractive hauls in the following weeks (Ouellet 1994).

Most employee-drivers are paid by piece rate, structured as a certain number of cents per mile for the standard miles associated with each dispatch, but this per mile pay is substantially lower than that received by leased-on owner-operators because the carrier is providing the truck and covering its costs (Miller et al. 2018). While some employee drivers are paid a percentage of the freight bill, this is also a form of piece-rate pay. The rare drivers who are paid on an hourly basis are usually providing services atypical of long-distance TL operations (Ouellet 1994).

At the same time, TL carriers using employee drivers will often add other specific components to compensation and, where legally feasible, some of these are extended to leased-on owner-operators. A standard category is supplemental piece-rate payments for specific tasks besides driving; examples include loading or unloading freight by hand or checking the overall weight and axle-weight distribution of a load. Most carriers compensate drivers for performing these tasks with a fixed payment for each task, regardless of the time taken in each individual case, thus maintaining the piece-rate format. In addition, a carrier may pay drivers, usually after some specific waiting period, for being detained by a shipper or a receiver who is taking an excessive amount of time to load or unload a trailer that the driver cannot simply drop (unhook from the tractor) and leave behind.

Some carriers pay by the hour for excessive detention time, but it is common for this to be a lump sum payment, which again continues the piece-rate approach. The second type of supplemental pay may be a bonus program, the intent of which is to directly incentivize specific behaviors that are not fully captured in, or which may even modify, the incentives provided by the basic piece rate of a given cents per mile. Typical incentives are for meeting specific fuel mileage targets and for operating without crashes (James 2023; Smartdrive 2023).

Most employee-drivers will receive some form of fixed compensation, as will be discussed below. The most typical form is regular contribution to fringe benefits, such as payments toward the premiums for health insurance. The committee is also aware that at least one large long-distance TL carrier has recently experimented with a compensation model that was once associated with unionized drivers in the pre-deregulation era: “hours and miles.” In this format, a driver is paid by the mile while driving but on an hourly basis when on duty and not driving. Schneider National, Inc., advertised some jobs with this compensation method in 2023 (Schneider 2023a, 2023b).

There are no nationally representative data on the patterns of compensation of employee drivers. Although there are two main sources of compensation data, both are limited. One source is a survey of self-selected carriers who chose to respond to a compensation survey administered every 3 or 4 years by the American Trucking Associations (ATA), which includes

an unstated number of long-distance TL carriers. This source is proprietary and constrained by copyright limitations. As a result, no excerpts are presented here. The second source is the National Survey of Driver Wages (NSDW), which is administered by the National Transportation Institute9 on an ongoing basis every quarter. Based on the advertising for this source, the survey results are used for wage benchmarking by carriers in different parts of the for-hire trucking industry. However, these NSDW data are also proprietary and constrained by copyright and confidentiality rules.

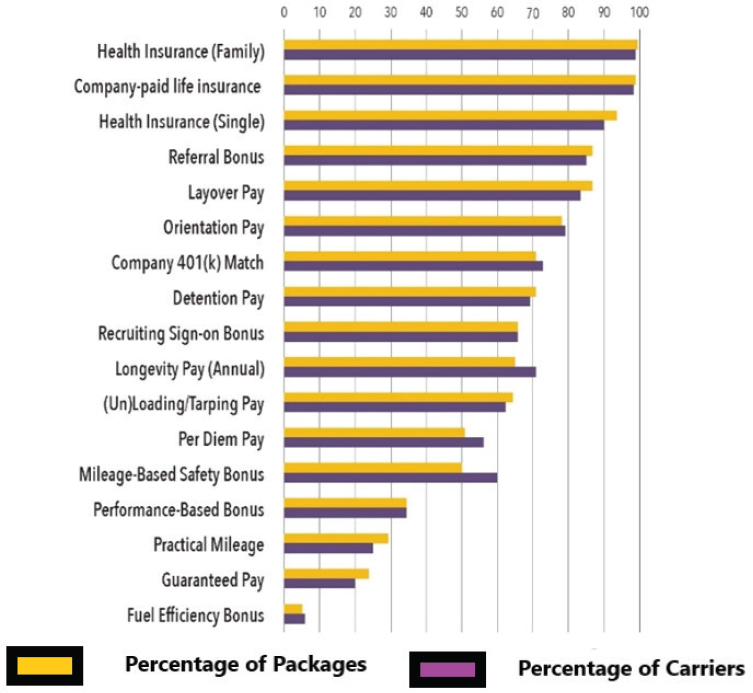

Although the committee was not able to obtain a current version of the NSDW survey data, an academic researcher with access to data from 2018 was able to share some descriptive statistics about the range and frequency of compensation components within the database’s self-selected sample of TL carriers. The surveyed carriers offered a wide range of benefits, as shown in Figure 3-1. Notably, more than 90 percent of the compensation packages in the sample consisted of health insurance and life insurance. A high proportion of carriers also offered referral bonuses; layover pay (83%); and orientation pay (79%). TL carriers that reported providing “practical mileage” pay means that drivers are paid for miles traveled that reflect real world conditions, such as added miles to follow detours and avoid roadway weight and height restrictions. “Guaranteed pay” reflects the fact that some TL carriers insure drivers against large variations in weekly pay as long as the driver is available a minimum amount of time (e.g., 6 workdays) creating a minimum weekly pay floor. Per diem pay is a form of reimbursement that is nontaxable for meals and other incidental expenses incurred by the driver while working.

Figure 3-1 shows that approximately 70 percent of the surveyed TL carriers offer some form of detention payments, with a similar percentage making up the total set of benefits being provided. Typically, these are paid as a lump sum, paid after a minimum amount of “free time;” this retains the driver’s incentive to contribute to leaving quickly to the extent it is under the driver’s control, once the free time is exhausted. Similarly, most of the surveyed TL carriers (60%) offered drivers a mileage-based safety bonus, reflecting an attempt by carrier management to moderate the basic incentive effect of mileage-based pay. Although these data should not be extrapolated to the universe of TL carriers due to its small and self-selected sample, it does highlight the types of incentive and non-incentive payments that large carriers employ.

___________________

NOTES: NSDW data were collected by the National Transportation Institute for a sample of up to 200 TL carriers in a given quarter. The dataset contains approximately 80 variables, including compensation type and level, benefits information, and average length of haul for the carrier. Some surveyed carriers reported multiple compensation packages, each associated with a specific type of work or driver experience level.

SOURCES: Data analyses by Walter Ryley, Bowling Green State University, in work commissioned for the study. Original data from the NSDW sample of self-selected carriers during the fourth quarter of 2018.

REASONS FOR PIECE-RATE PAY

In most lines of business, employees are paid on an hourly or salary basis that is independent of output (Holmstrom and Milgrom 1994). Long-distance truck driving, especially in the TL sector, compensates for work in the less common, but not unusual, piece-rate manner, albeit with variants in specific methods.10 The primary reason for piece-rate compensation (i.e., based on some measure of output) is to reward hard work and consistent effort in a job that lacks many other forms of worker motivation such as direct oversight by supervisors and teamwork influences (i.e., work in a group setting where success depends on each team member contributing). Considered in this context, piece-rate pay can align carrier and driver economic incentives (e.g., reducing the driver’s interest in taking many unproductive breaks) (Baker and Hubbard 2004).11

The piece-rate approach originated in the early days of trucking, when the information asymmetry between the carrier’s managers and drivers on the road was large due to the limited ability for managers and drivers to communicate (Hubbard 2000). For example, until the advent of two-way communication between truckers and dispatchers, the latter were usually unaware of the status of the load until the driver pulled over and called the dispatcher from a payphone with an update on the truck’s location (Hubbard 2003). Technology advances (e.g., satellite and cell network links to trucks, video cameras in trucks, and electronic engine management systems that track truck operations) have since reduced these communications barriers to lower the cost and uncertainty of monitoring long-distance drivers and their work effort (Viscelli 2016; Levy 2023). Piece-rate pay persists nonetheless, which suggests that information asymmetry remains a challenge for carriers or that other factors at play. An example of another factor is that piece-rate pay allows the carrier to avoid paying the driver for unproductive work periods, such as when the truck is detained at a shipper’s location, thereby shifting the risk of delay onto drivers (Belzer 2000). If a piece-rate compensation system induces higher productivity by running the truck hard in ways that produce undesirable and costly outcomes, for instance by increasing fuel burn or prompting more aggressive driving, then a

___________________

10 The linehaul drivers for LTL carriers, who operate primarily between the terminals owned by the carriers, are usually paid piece rate in contrast with the local pickup and delivery drivers, who are primarily paid by the hour (Burks 1999; Burks and Guy 2012).

11 Ouellet (1994), writing from a sociological perspective, suggests that the inability of truckers to fully display their occupational skills, as opposed to other professions like machinists, results in truck drivers taking great pride in the volume of work that they can do (e.g., staying “in the saddle” for hours on end). This suggests—as noted above—that motives other than straight financial incentives may be important in long-distance TL driving.

carrier may provide bonuses to counter this effect, such as by offering safety and fuel mileage goals as reflected in the data in Figure 3-1.

In addition to the carrier’s interest in prompting consistent and high work effort, there are other reasons for carriers, especially smaller ones, to prefer piece-rate compensation. Significantly, piece-rate pay guarantees a given outlay for the driving service, which is not the case for hourly pay. Carriers in a highly cost-competitive business might not be confident in their ability to identify an hourly rate that would keep total pay outlays comparable to levels now paid, especially if hourly pay changes the incentives for consistent and sustained effort. For practical reason too, a small carrier may also prefer piece-rate pay if changing accounting systems and software to support non-piece-rate pay methods, such as hourly pay, is believed to be costly. However, the fact that larger carriers, which have dedicated and sophisticated accounting and IT staff, also rely on piece-rate pay suggests that such practical concerns may not be a real issue.

It should be pointed out, however, that TL carriers can have incentives to avoid piece-rate pay if a goal other than pure work effort is desired. A concrete example is long-distance specialized freight in which the work involves loading, hauling, and unloading a tank truck carrying hazardous chemicals. This work is sometimes paid on an hourly basis, with one reason being that the carrier may worry about the risk of civil liability from a crash or a mistake in loading or unloading. Hourly pay may remove the potential incentive created by piece-rate pay to push hard or to exceed highway speed limits (Ouellet 1994). In addition, drivers performing a job that exposes the carrier to this level of potential liability may be selected more carefully or be required to have more crash-free experience than are drivers in other types of truckload jobs. These drivers, therefore, may be in a better position to demand non-piece-rate pay that leads to more predictable levels of compensation.

SUMMARY POINTS

An important concluding point is that almost all long-distance TL drivers are provided some form of piece-rate pay as their main, but not exclusive, form of compensation. When non-piece-rate is used, such as hourly pay, it is typically associated with a different type of driver (e.g., specialized in hazardous materials) and set of work requirements and conditions than are prevalent in the long-distance TL sector. Consequently, even if a researcher using a large dataset could identify the methods of pay for each driver and finds that some are paid hourly rather than by piece rate (e.g., pay by mile), the driver qualifications, work requirements, and working conditions would probably not be comparable so as to introduce many confounding factors.

A second key point is that the incentives for work effort created by the piece-rate pay methods that are common in the TL sector are the strongest for independent owner-operators, less strong for leased-on owner-operators, and weakest for employee drivers. The reason for this difference is that for-hire owner-operators have more at stake in meeting their piece-rate output, which must cover many expenses in addition to their driving time, such as for fuel, vehicle maintenance, and overhead. Leased-on owner-operators have less at stake than independent operators, but still more than employee drivers who do not need to meet piece-rate goals to pay for the fuel and equipment they use, for example. An important implication is that efforts to understand how piece-rate compensation methods, such as pay-by-mile, can influence driver behavior must distinguish among these types of drivers in the TL sector and how their incentives to meet piece-rate output may differ. These considerations are raised again in Chapter 5 when examining compensation methods and safety performance.

REFERENCES

Baker, G. P., and Hubbard, T. N. (2004). Contractibility and asset ownership: On-board computers and governance in U.S. trucking. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(4), 1443–1479.

Belzer, M. (2000). Sweatshops on wheels: Winners and losers in trucking deregulation. Oxford University Press.

Caplice, C. (2007). Electronic markets for truckload transportation. Production and Operations Management, 16(4), 423–436.

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA). (2023, May 1). FMCSA forms new task force to combat predatory leasing practices. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration Newsroom. https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/newsroom/fmcsa-forms-new-task-force-combat-predatory-leasing-practices.

Gittleman, M., and Monaco, K. (2020). Truck driving jobs: Are they headed for rapid elimination? ILR Review, 73(1), 3–24.

Holmstrom, B., and Milgrom, P. (1994). The carrier as an incentive system. American Economic Review, 84(4), 972–991.

Hubbard, T. N. (2000). The demand for monitoring technologies: The case of trucking. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(2), 533–560.

Hubbard, T. N. (2003). Information, decisions, and productivity: On-board computers and capacity utilization in trucking. American Economic Review, 93(4), 1328–1353.

James, B. (2023). The benefits of a driver safety incentive program. Tenstreet. https://www.tenstreet.com/blog/safety/the-benefits-of-a-driver-safety-incentive-program.

Kingston, J. (2021, July 29). Court decision serves as primer on pitfalls, possibilities of truck leasing. FreightWaves. https://www.freightwaves.com/news/court-decision-serves-as-primer-on-pitfalls-possibilities-of-truck-leasing.

Levy, K. (2023). Data driven: Truckers, technology, and the new workplace surveillance. Princeton University Press.

Lynch, F., Kolenikov, S., et al. (2014). Attitudes of truck drivers and carriers on the use of electronic logging devices and driver harassment. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration.

Miller, J., Saldanha, J. P., et al. (2018). How does electronic monitoring affect hours-of-service compliance? Transportation Journal, 57(4), 329–364.

Muir, W. A., Miller, J. W., et al. (2019). Strategic purity and efficiency in the motor carrier industry: A multiyear panel investigation. Journal of Business Logistics, 40(3), 204–228.

Office for Consumer Populations. (2023). Consumer risks posed by employer-driven debt. Washington, DC.

Ouellet, L. J. (1994). Pedal to the metal: The work lives of truckers. Temple University Press.

Rakowski, J. P. (1988). Marketing economies and the results of trucking deregulation in the less-than-truckload sector. Transportation Journal, 27(3), 11–22.

Schneider. (2023a). Over-the-road (OTR) van truckload truck driver - eastern 37 states. Schneider-Jobs.com. https://schneiderjobs.com/search-driving-jobs/details/212236.

Schneider. (2023b). Regional van truckload truck driver. SchneiderJobs.com. https://schneiderjobs.com/search-driving-jobs/details/230300.

Smartdrive. (2023). Build your driver incentive program; Discover the secrets to a successful driver incentive and retention program. Smartdrive by Omnitracs. https://try.omnitracs.com/driver-incentive-ebook.

Viscelli, S. (2016). The big rig: Trucking and the decline of the American dream. University of California Press.

This page intentionally left blank.